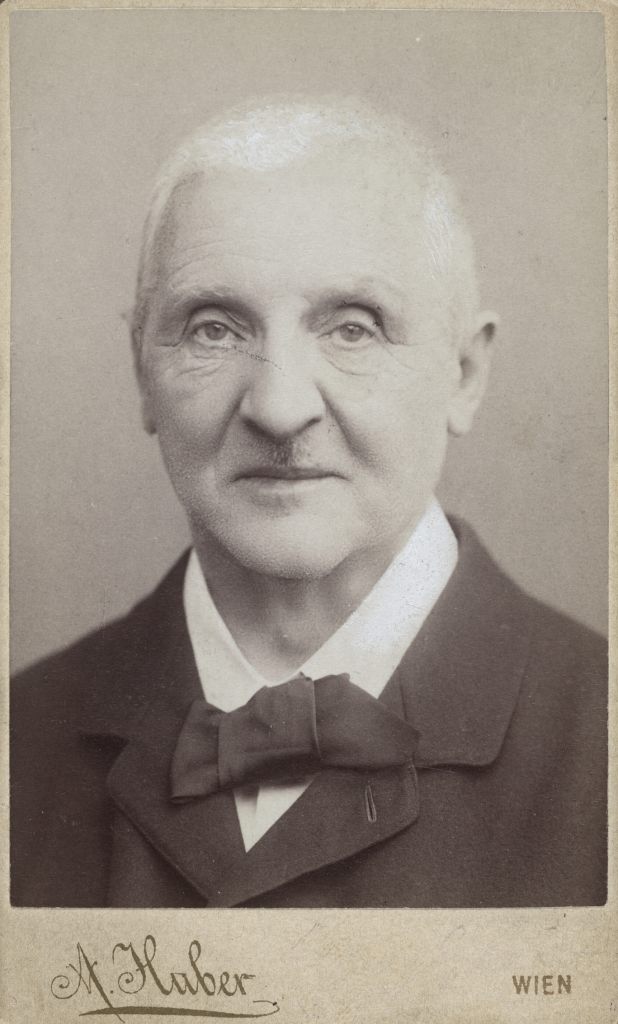

At the very beginning of his jubilee year, this now world-famous composer was honoured by the Vienna Philharmonic at their New Year’s Day concert with a performance of his Quadrille WAB 121 in a version for orchestra. The great symphonist Anton Bruckner, born on 4 September 1824, taught for many years at our university’s institutional predecessor and is also set to be particularly present at the mdw in his bicentennial year of 2024, with the Anton Bruckner Department of Choral and Ensemble Directing and Music Theory in Music Education paying tribute to its namesake in a wide-ranging programme of events.

Anton Bruckner was exposed to both teaching and music at an early age. His father and grandfather had worked as schoolteachers in rural Upper Austria, and the young Bruckner initially went on to follow in their footsteps. During the 19th century, the position of schoolteacher in rural areas included responsibilities pertaining to church music—for which reason Bruckner’s own passion for music was sparked quite early on. Following completion of various stages of training, including as a boy chorister at the Augustinian monastery of St. Florian, he was hired in 1841 as an assistant teacher in Windhaag bei Freistadt—where he began teaching in his own right once he had earned his certification. He then continued his education on the side, eventually qualifying to teach at higher schools. Bruckner’s true and continually growing fascination, however, was with music, its composition, and its improvisation—and numerous early works such as the Windhaager Messe of 1842 attest to Bruckner’s creative drive even during his youth. 1868 saw Bruckner move to Vienna, and he began teaching at the Conservatory of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (the predecessor to today’s mdw) in the autumn of that year. Though 1868 also witnessed the world première of his First Symphony WAB 101 at the Redoutensaal in Linz, acceptance of his music in the Viennese music scene—then dominated by the likes of Johannes Brahms and Eduard Hanslick—was to be denied him for quite some time. 1875 saw Bruckner assume an initially unpaid position as a lecturer in harmony and counterpoint at the University of Vienna.1 While it was future professional musicians that Bruckner taught at the Conservatory, the students whom he taught at the University of Vienna had no prior knowledge of music theory—and in his lectures at the latter, he adapted his teaching of the same content to better suit his less advanced charges. All the while, Bruckner also taught private pupils.2

The tension between teaching and studying is evident in many respects all across Bruckner’s artistic career. His learning experiences with the conductor Otto Kitzler and the music theorist Simon Sechter had a lasting impact on his teaching style: “To Bruckner, every teacher always remained an authority whom one had to obey,”3 writes Thomas Leibnitz in description of Bruckner’s attitude as a learner. He most probably also demanded such “obedience” of his own pupils, with whom close, familiar, and long-lasting relationships formed even so. Bruckner’s ingenious favourite pupil Hans Rott, a close friend of Gustav Mahler, shared his teacher’s fate insofar as he was not accepted by the academic establishment, and Rott was unfortunately to meet an untimely and tragic end in a psychiatric institution. Bruckner’s best-known pupils, who also participated in his works’ world premières and further dissemination, included figures such as the brothers Joseph and Franz Schalk, Ferdinand Löwe, and Friedrich Klose. It is thanks above all to the efforts of his pupils that Bruckner’s music came to be performed beyond the confines of Vienna and ultimately became more widely known. Here too, however, a certain tension remained: even though Bruckner himself repeatedly sought advice from his pupils, some of them—such as the Schalk brothers—would occasionally “edit” the composer’s works prior to their premières without his knowledge. The original version of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 5 in B-flat Major WAB 105, for instance, was only rediscovered in the 1930s.4

“Bruckner’s works are permeated by the 19th-century realms of experience through which he progressed: from an Upper Austrian village to the burgeoning provincial capital of Linz and on to Europe’s metropolises; from the village schoolhouse to the teacher’s college and on to the Conservatory and the University […].”5 The interplay between his output and teaching of music and the constant exchange with his institutionally and privately taught pupils characterised Bruckner’s artistic biography and had a lasting influence upon his oeuvre.

- Cf. the timeline compiled by Alexandra Jud und Damaris Leimgruber in Hans-Joachim Hinrichsen (ed.): Bruckner-Handbuch, Stuttgart, 2010.

- Cf. Uwe Harten, Anton Bruckner: ein Handbuch, p. 389, Salzburg and Vienna, 1996.

- Thomas Leibnitz, “Bruckner und seine Schüler,” p. 31, in Hans-Joachim Hinrichsen (ed.): Bruckner-Handbuch, Stuttgart, 2010.

- Thomas Leibnitz, “Bruckner und seine Schüler,” p. 35f, in Hans-Joachim Hinrichsen (ed.): Bruckner-Handbuch, Stuttgart, 2010.

- Felix Diergarten, Anton Bruckner – Ein Leben mit Musik, Kassel, 2023.