On 9 July 2020, former mdw student Gisela Zdenek will be turning 100. Research in the run-up to her birthday celebration led members of her family to the mdw Archive, which in turn drew our attention to this strong-willed woman’s life history—which has always been accompanied by music. We had a birthday conversation with Zdenek about her time at the “Academy”.

During the mid-1930s, a good three-quarters of our institution’s young piano students were women. Gisela Zdenek was one of those young women who pursued the dream of becoming a musician. She studied piano during Austria’s dictatorial rule by the National Socialists, whose proscriptions and persecutions also affected what was then the Academy of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna. It was back in 1936 that Gisela Zdenek, née Hanausek, appeared for her entrance exam at the Academy. She remembers: “I did my entrance exam for a Jewish professor—but three months later, he disappeared. So I ended up switching to Prof. Hans Weber.”

Gisela Zdenek came to music through her family. Both her mother and her “brother-uncle”, as she affectionately refers to him on account of their only slight difference in age, were musically talented individuals. “I got along especially well with my brother-uncle Alois. He needed my piano playing for his singing,” she says with a wink. Zdenek’s parents worked hard to provide their daughter with piano lessons and, later on, her own upright piano. “That was during the 1930s—an awful period. Nobody had any money, and my parents were no exception.”

She ended up at the Academy thanks to her music teacher, who recognised her talent early on and motivated her to take the entrance exam. “I could have done various apprenticeships. My mother’s cousin, for instance, had a hair salon. But I wanted to study music.” Ever since the mid-19th century, piano had been the most popular subject among the young women studying at the Academy in Vienna, many of whom dreamed of pianistic careers—as did Gisela, who was then 16 years old.

Barely two years after she’d begun her studies, Austria was “annexed” by National Socialist Germany. “One day, I left the Academy and went to the tram, crossing Schwarzenbergplatz to reach the Ring. Over on Heldenplatz, Hitler was giving a speech. It was the day when everything changed. Though for me, nothing changed. The main thing for me was that I was allowed to study at the Academy— because getting accepted there wasn’t so easy,” Zdenek recalls. At that time, more and more students were being forced to end their studies: “Many of my colleagues who’d been studying with me just weren’t there anymore the next day,” she remembers, clearly pained. Nearly 50 % of the Academy’s teaching staff lost their jobs due to the termination measures implemented immediately following the National Socialists’ seizure of power, and around 100 students had to leave the Academy on racial grounds. (See “History of the mdw”).

Sometimes I’d practice as much as six hours a day. It was always at least four.

Gisela Zdenek

But despite everything, Gisela Zdenek still cherishes the memory of her time at the Academy. The pianist repeatedly describes her time studying here to have been one of the most wonderful periods of her life. “I attended a concert nearly every day. As a student back then, I was able to get tickets for practically nothing. My favourite place was the Musikverein; I knew that building from cellar to attic.”

During her studies, however, she gradually realised just what being a pianist entails and requires. “I’d always get such shaky knees—but a concert pianist needs to have her knees under control,” she remarks with a laugh, “so I knew that playing publicly wasn’t for me.” When Prof. Hans Weber was called up for military service in 1941, she switched to Grete Hinterhofer for instruction in her chosen major.

One year later, on 23 July, she married her husband Paul Zdenek—and shortly thereafter, she became pregnant. The fact that she continued her training nonetheless was by no means a given, and not everyone looked upon it kindly. “Professor Hinterhofer once asked me what I actually needed a diploma for, since I was already married anyway. I think she was jealous—after all, she was unmarried and had no children,” is how she assesses that today.

After her son’s birth, Gisela Zdenek did encounter some difficulty continuing her studies, and she eventually transferred to the Conservatory of the City of Vienna to study with Viola Thern. It was thanks to her mother that she was able to continue her training. “If I hadn’t had her, I wouldn’t have been able to keep on studying. She took care of her grandchild while I was out being taught.”

Paul Badura-Skoda was a universal genius.

Gisela Zdenek

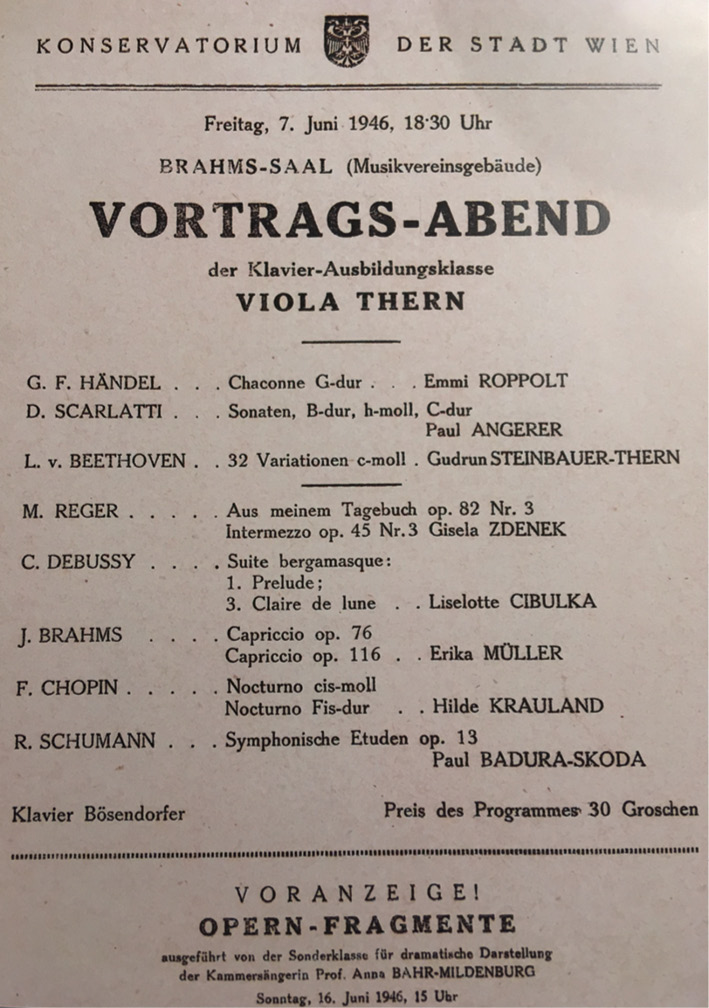

At the Conservatory, she encountered Paul Badura-Skoda and Paul Angerer, both of whom would become prominent figures later on. A programme documents a performance given by these two on 7 June 1946 in the Vienna Musikverein’s Brahms-Saal.

It was with a heavy heart that she was ultimately forced to give up her dream of becoming a performing musician. “It would have been nice, but it wasn’t to be.” From that point onward, she taught piano herself in her apartment in Vienna’s second district. “If I’d wanted to, I could’ve made a living from it. At the time, I was teaching over 15 students—and I could’ve had even more.” Zdenek says that teaching did, at any rate, provide her with a nice supplementary income, and she continued to do so until she was 38.

It’s with no small emotion that she thinks back to the old Ehrbar grand that adorned her parlour for many years. “My concert grand took up nearly two thirds of the room, which is something my husband wasn’t really happy with,” she says with a grin.

Even today, as she approaches the age of 100, Gisela Zdenek still plays now and again—despite how she’s very dissatisfied with what she’s able to do. “You learn so much, and when you get old, it’s all gone. Or you still know it, but you can no longer manage it physically.” After a short pause, however, she adds with a firm voice: “But what I was capable of back then was concert-quality!”