This statement, inscribed like a commandment on the walls of the Max Reinhardt Seminar in Penzing, is every bit as valid now as it was back when Reinhardt first made it: onstage and before the camera’s lens, one needs to be authentic and true in order to captivate one’s audience. And a look at teaching practice at the mdw shows how studying at the Max Reinhardt Seminar means being thoroughly prepared to do just that.

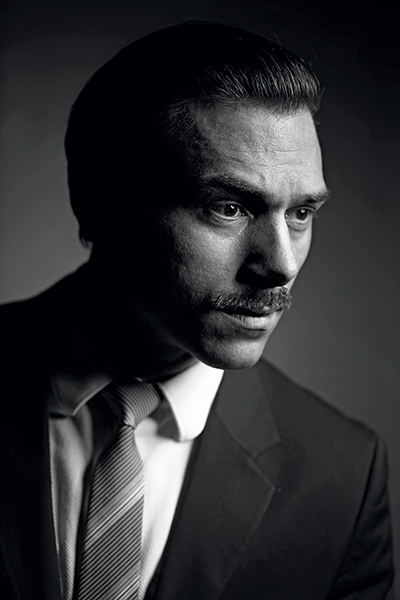

Nowadays, the distinction between theatre and film actors that became common with the advent of silent movies and then talkies is considered obsolete. And it’s for more than just financial reasons that well-established as well as young actors now do both and usually can’t avoid dealing with audio(visual) media. Viennese author and director Sebastian Brauneis, who has been teaching Arbeit vor der Kamera [On-Camera Work] since 2014, is certain that “this will become even more true as time goes on. We’ve all got screens in our pockets, we do most of our work in front of screens, and screens are now even replacing classic posters and billboards. All these screens are empty surfaces that need content, and someone’s got to convey this content plausibly.” But the point here is not to transfer performances directly from the stage to the screen. While a moment onstage is something we see once and never again, the camera permanently preserves what it captures. And that has its effect on those being captured. “On set, the camera can sometimes seem like an inscrutable black hole,” says Brauneis. “Onstage, gestures remain incapable of being reproduced—it’s a momentary experience. But if I make a mistake on camera, that mistake is permanently documented. What’s more, doing film takes a lot of highly specialised people and complex technology, and all that is extremely expensive. Combine that with the knowledge that what you’re creating is potentially immortal, and the pressure that results is huge.” But even so, he says, the camera can also be liberating: “It’s an honest partner and accepts us as we are. And unlike human beings, the camera doesn’t make value judgements. It’s a truthmachine, but above all a possibility-machine.”

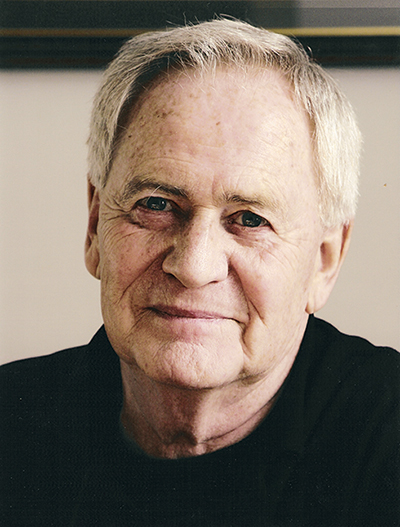

Hungarian director and Oscar-winner István Szabó is responsible for the seminar Fernsehund Filmarbeit [Television and Film Work], and he, too, knows the challenges that the students have to take on: “The camera makes possible up-close portrayal of the thoughts and feelings that manifest themselves in the human face and the human gaze, and it also shows how these transform into different, new thoughts and feelings. So on camera, something one does with a gesture in theatre can perhaps be done with a certain gaze or by changing one’s gaze in a certain way. The requires from the actors personal feelings, a strong presence, and constant intensity. Acting in films requires complete naturalness, the power of silence, secret thoughts and emotions, and the tools needed to act without any tools.” In his seminar, students practice mainly by filming close-up shots: “The special challenge in acting for the camera is to portray a certain truth authentically, true to reality, down to the last detail. On the big screen, the camera tolerates no stylisation whatsoever. ‘Acted’ feelings or an empty gaze are instantly exposed by the camera. And a movie’s audience will only go along with a passion if they feel it’s authentic and credible. This is the realisation that the students need to have.”

In both seminars, the 3rd- and 4th-year students develop, rehearse, film, and then analyse scenes. “A big point is also to understand that film follows its own form, its own rhythm, and it adheres to special laws,” says Brauneis. So alongside being introduced to the theory, the main goal is to become familiar with the vocabulary of film and understand how a set works. Also essential is practicing how to handle emotions, the body, posture, and language.

Serious filming is then done in cooperation with Film Academy Vienna at their film studios on the mdw campus at Anton-von-Webern-Platz; this relationship functions extremely well and makes everything possible in the first place. Students of Film Academy Vienna participate voluntarily, and the acting students— surrounded by a complete film set in a highly professional studio—can shoot scenes for subsequent analysis.

This year, Mel Churcher—an acting and speech coach from England—visited the Max Reinhardt Seminar and worked with its students for the first time. Churcher herself gathered many years of stage and acting experience before becoming a coach to international stars including Benedict Cumberbatch, Milla Jovovich, Angelina Jolie, Jet Li, and numerous others. She thus knows both sides—in front of and behind the camera. (See Florian Reiners’s interview with Churcher on the next page.)

Being “authentic” on camera, says Sebastian Brauneis, has a lot to do with bravery. “It’s all about being brave; being brave means having the courage to do something, and to have courage, you need trust,” he explained in his interview with mdw Magazine. There is no universal recipe for this which, he says, is a good thing: “We instructors have a constant urge to take on new challenges and work with individuals with whom we have to reacquaint ourselves time and time again. It can’t ever be about ‘standard operating procedures’,” though having basic training in the “mechanics”, he says, is essential even so: for only when the students know their “tools” can they decide what to do with them.

For István Szabó, as well, it’s first and foremost about students’ uniqueness: “Students should get to know the joy of being true to themselves. They shouldn’t have an urge to be like anyone else, to imitate anyone else’s behaviour or style. They should be happy that they—like every human being—are unique; there’s only one of them. They should want to do what’s possible with their faces bravely, freely, and honestly, as something that—just like their emotions and instincts—is solely theirs. So in the characters they portray, they should search for themselves.”