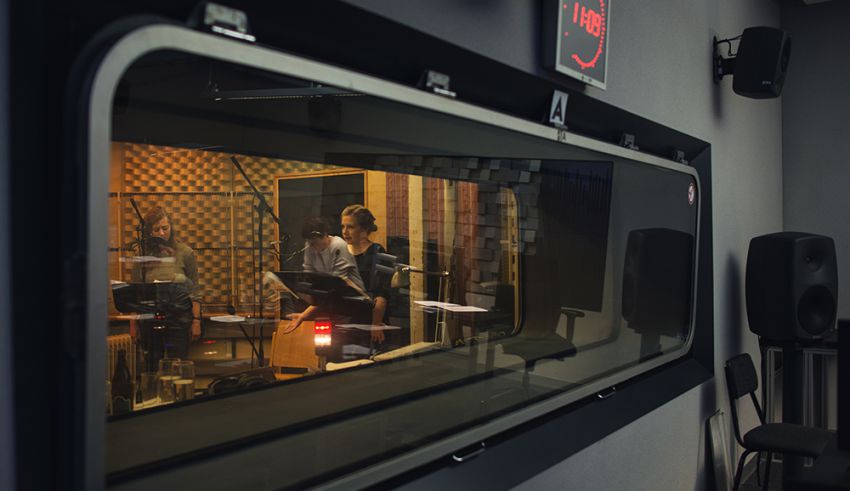

“One needs to feel how you have a problem,” says Max Reinhardt Seminar instructor Harald Krewer to his students, as he explains the basic mood of a text passage at the recording studio of the ORF-Funkhaus radio broadcasting facility. In the course entitled Hörspiel [Audio Drama], acting and directing students of the Max Reinhardt Seminar learn how mount such a production together. The acting students attempt to read their texts with maximum intensity, while the directing students work to guide them with instructions that are clear as possible. Text fragments are read aloud over and over, with every intonation, every exhalation, every pause subjected to detailed scrutiny. It soon becomes clear: such concentration on the voice as the dominant narrative tool is a demanding art. And the degree to which this succeeds determines whether the listeners want to follow the story and how gripping a text is. Neither props, nor lighting nor camera techniques are there to support the dramaturgy; the voice alone, accompanied by music and sound effects, must tell the story.

The compulsory course Hörspiel is divided into three parts. An initial unit provides students with an introduction to audio drama and its various forms. Radio plays from various eras and featuring different actors are listened to in order to get an impression of the wide range of interpretive options. The directing students then select a text that they would like to record with the acting students. In the practical unit that follows, recording is done with an audio engineer at the ORF Funkhaus on Argentinierstraße. Within two days – the production phase is deliberately kept to a minimum in order to also school time management – the students develop and realise their interpretation of the text under Harald Krewer’s guidance.

This course’s third unit then centres on production of the final version, complete with music and sound effects. Essential is that the radio play be finished independently by the students, because the point here is not to produce something for the archives; instead, the students’ finished play is broadcast on Radio Ö1, thus allowing it to reach a large audience.

“The fascinating quality of the radio play medium is as strong as ever,” says Harald Krewer with conviction. Prior to the era of television, when radio was still the main broadcast medium, the radio plays broadcast on government stations embodied true “hits”. They were performed live in the studio and included live music. Occasionally, actors would even step up to the microphone in costume. And prior to the digital age, realising sound effects for radio plays took significantly more work than it does today. Every sound either came from a tape or was made live in the studio. The studio of the Funkhaus is still home to artefacts from that era – including numerous sets of stairs, windows, and doors that were once used to create footsteps, windows opening, doors slamming, and many other sounds. These days, such sounds are frequently lifted from films and videos – making it all but unnecessary to go and record one’s own material for typical sounds. The literature used for radio plays has also changed, since it’s become quite rare for authors to write new texts specifically for this medium – as figures such as Ilse Aichinger and Ernst Jandl still did.

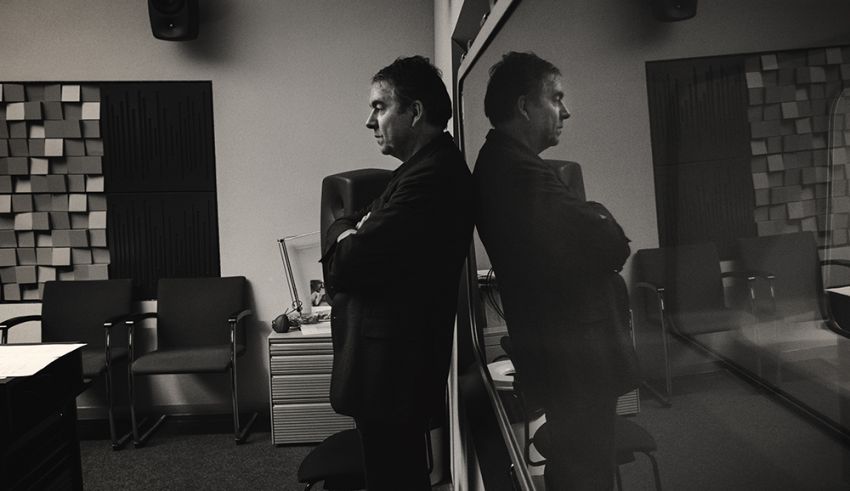

In his teaching, Harald Krewer also tries to convey the radio play tradition. And Krewer is himself a graduate of the Max Reinhardt Seminar, which is where he first discovered his own interest in radio plays. While he also worked as a stage director early in his career, his activities eventually shifted entirely to the recording studio. Alongside teaching at the mdw, he also works for Ö1 as a radio play director and additionally runs his own audio production company and audio book publisher.

“Radio plays’ reduction to the spoken word and a well-told story is what makes them so fascinating,” says Krewer of his passion for audio drama. And for his students, radio plays also represent a special challenge: unlike in stage productions or in films, directors and actors are separated by a glass panel and often even do without direct eye-contact, with stage directions being relayed solely by microphone. And while theatre and film roles are often rehearsed for weeks, with the actors putting long hours of hard work into a particular text and eventually memorising it, actors record radio plays with the text right in front of them – and there is only little time for developing individual interpretations. Texts need to be studied fast. And directing students, for their part, have to learn to communicate their instructions to the actors in the most precise possible manner.

“Performing radio plays is more comparable to performing music, with the text being the score,” says Harald Krewer. Changes in rhythm, volume, pauses, and the readers’ vocal timbres determine a radio play’s quality, much like it is with a song. So the actors have to structure their text carefully while developing a feel for its melody – and in both of these challenges lies the true art of a successful radio play.