Der Fachbereich Volksmusik vor der Institutsgründung

Das Institut für Volksmusikforschung und Ethnomusikologie, die größte Forschungs- und Lehreinrichtung dieses Fachbereichs in Österreich, besteht an der mdw seit 60 Jahren. Entsprechend beginnt die Institutsgeschichtsschreibung gemeinhin mit 1965. Volksmusik und Volksmusikforschung existierten am Haus allerdings schon lange davor. So wie in den Jahrzehnten nach der Institutsgründung stand auch davor die österreichische alpenländische Volksmusik im Zentrum des Musizierens, Lehrens und Forschens – notabene unter unterschiedlichen politischen Vorzeichen.

Bislang unzureichend thematisiert wurde die Rolle der Volksmusikforschung, -pflege und -praxis an unserem Haus während des Nationalsozialismus. Unterricht in Volksmusik und Volkstanz fand schon vor 1938 statt. Beispielsweise in den Lehrveranstaltungen Jugend- und Volksmusik von Oskar Fitz oder Volkstanz von Raimund Zoder. Mit der Machtübernahme der Nazis beendeten beide ihre Lehrtätigkeit. Zoder wurde gekündigt, der Name des wichtigen Volkstanzforschers begegnet uns nach 1945 wieder. Fitz verließ als prominentes NSDAP-Mitglied 1938 die damalige Reichshochschule, um die Musikschule der Stadt Wien aufzubauen, finanziert mit dem Vermögen des enteigneten Neuen Wiener Konservatoriums, an dem viele jüdische Lehrende tätig gewesen waren.

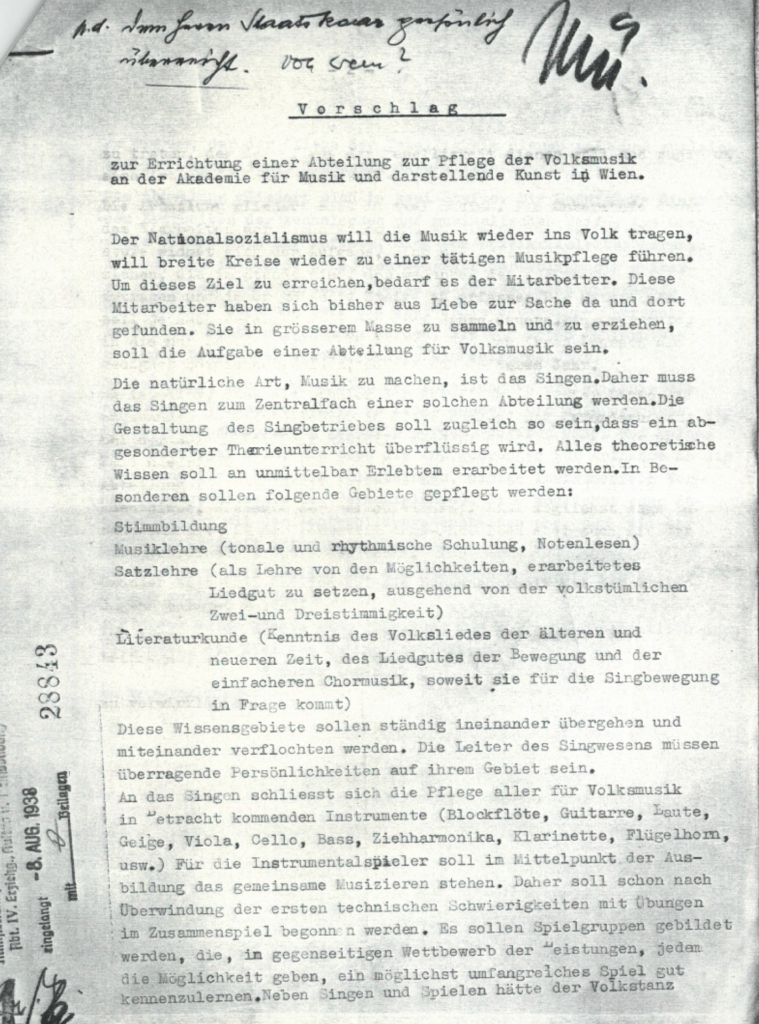

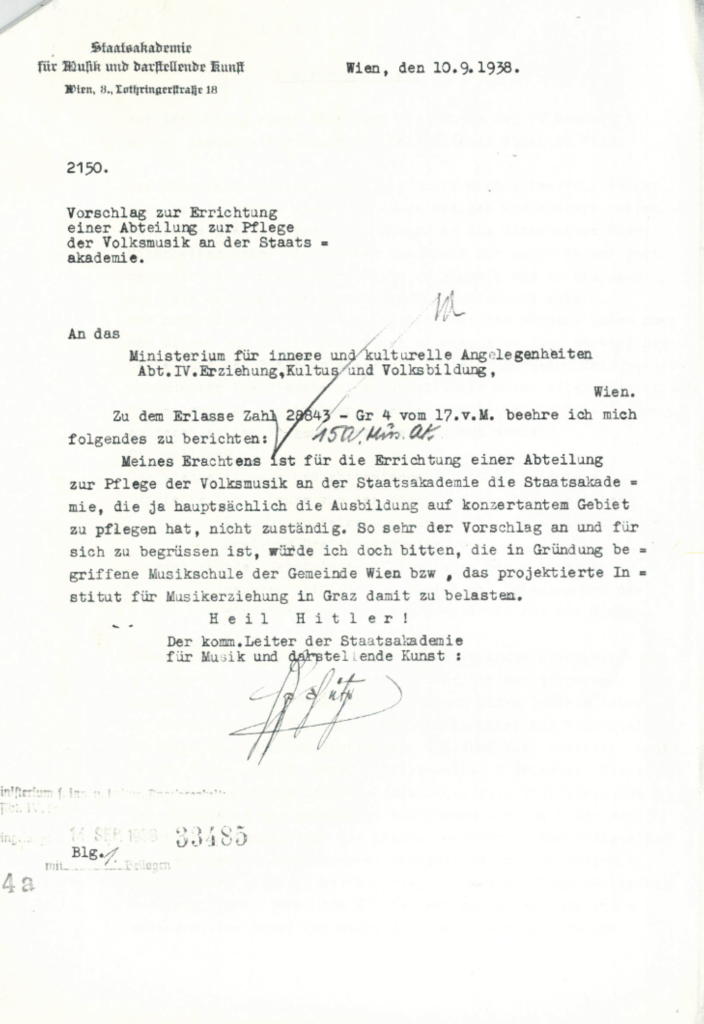

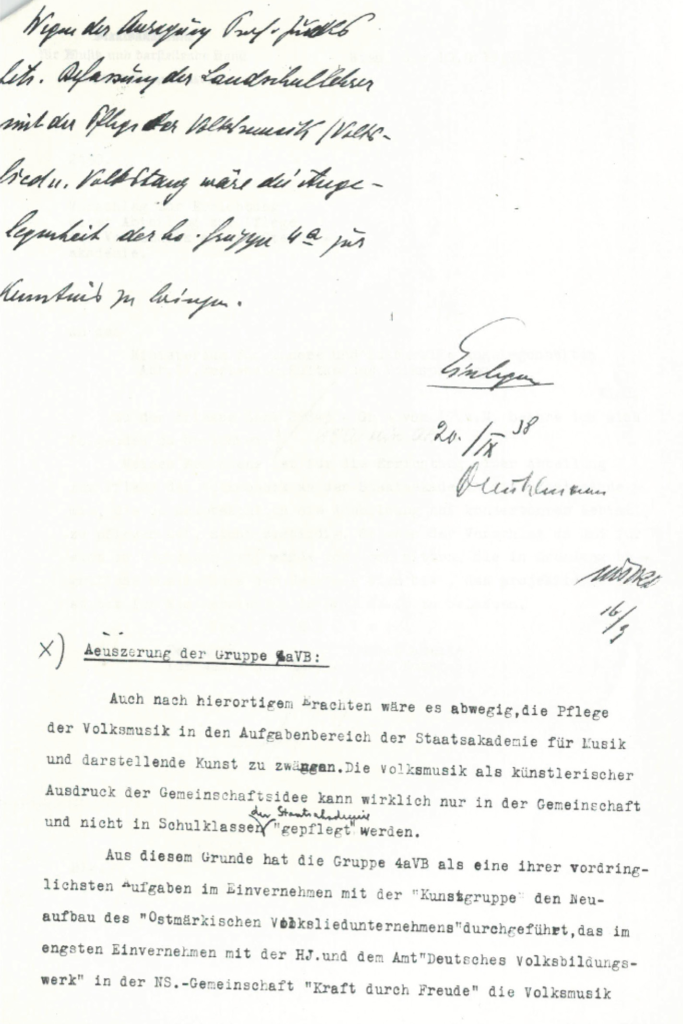

Bis 1938 war die Volksmusik- und Volkstanzausbildung Teil des musikpädagogischen Seminars an der Staatsakademie. Die Schulmusikausbildung wanderte dann an die erwähnte neu gegründete Musikschule der Stadt Wien. Es ist dies womöglich auch der Grund dafür, dass im August 1938 der Vorschlag zur Errichtung einer Abteilung zur Pflege der Volksmusik eingebracht wurde – „Von wem?“ ist handschriftlich auf dem Aktendokument vermerkt und bleibt offen. „Der Nationalsozialismus will die Musik wieder ins Volk tragen, will breite Kreise wieder zu einer tätigen Musikpflege führen“ argumentierte der Verfasser (Abbildung 1). Die Institution sah das anders. Die (noch) Staatsakademie, „die ja hauptsächlich die Ausbildung auf konzertantem Gebiet zu pflegen hat“ sei für die Pflege der Volksmusik nicht zuständig, so der Akademieleiter Franz Schütz. Auch Viktor Junk, Vorstand des Ostmärkischen Volksliedunternehmens (vor 1938: Österreichisches Volkslied-Unternehmen, heute: Österreichisches Volksliedwerk) stufte den Vorschlag einer Abteilungsgründung als „abwegig“ ein: „Die Volksmusik als künstlerischer Ausdruck der Gemeinschaftsidee kann wirklich nur in der Gemeinschaft und nicht in Schulklassen der Staatsakademie gepflegt werden“ (Abbildung 2 und 3). Diese Argumentation wird im Übrigen in vielen tertiären Musikausbildungsinstitutionen der Welt auch heute noch bemüht.

Volksmusik und Volkstanz waren während der NS-Zeit an der Reichshochschule auch ohne eigenes Institut stark vertreten, einige Beispiele: Von 1932 bis 1946 unterrichtete Eugenie Cloeter Volksliedpflege. Walter Goebl hielt von 1938 bis 1945 an der neu gegründeten Tanzabteilung die Lehrveranstaltung Volkstanz und Folklore ab. Von 1942 bis 1945 war Volksliedkunde und Brauchtumskunde Teil des Lehrangebots, unterrichtet von Richard Wolfram. Wolfram war nicht nur Mitglied der NSDAP, sondern auch der „Forschungsgemeinschaft Ahnenerbe“, einer SS-Forschungseinrichtung, die die rassistische Doktrin arischer Vorherrschaft verbreitete. Auch wenn Wolfram 1945 von der Universität Wien, an der er Professor für Germanistik war, zunächst entlassen wurde, begann er 1954 erneut dort zu lehren, wurde in weiterer Folge auch wieder ordentlicher Professor und Mitglied der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften – ein typisches Beispiel für die Wissenschaftskarriere eines NS-Faschisten im Nachkriegs-Österreich. Die konkreten Lehrinhalte von Wolframs Lehrveranstaltung bleiben Spekulation, seine politische Gesinnung ist aber eindeutig belegt und lässt eine politische Instrumentalisierung von Volksmusik und Brauchtum stark vermuten.

Nach dem NS-Regime begegnet uns im Jahr 1945 wieder der Name Raimund Zoders, der bis 1953 verschiedene Lehraufträge für Lehrveranstaltungen mit den Namen Brauchtum, Folklore und Volkslieder, Brauchtums- und Volkstumskunde oder Volksbräuche erhielt. Zoder wurde 1953 von Herbert Lager (Brauchtums- und Volksliedkunde, Musikfolklore) abgelöst. Zoder und Lager sind in der Fachgeschichte der Österreichischen Volksmusikforschung zentrale Figuren.

Besonders relevant in puncto Institutionalisierung des Fachbereichs an unserem Haus ist die Einrichtung eines Volkslied-Seminars (Seminar hier im Sinne von etabliertem Fachbereich) im Jahr 1949 unter der Leitung vom Pianisten und Komponisten Felix Petyrek. Petyrek forderte dringlich die Gründung eines Instituts für vergleichende Volksliedforschung. Im Fachverständnis weicht der nationalistische Zugang einer komparativen Perspektive. Petyrek betont die Relevanz der „ausländischen, auch der exotischen Volksmusik“ für die „Musikentwicklung der letzten Jahrzehnte“, von der die Studierenden in der NS-Zeit abgeschnitten waren. Sein Vorschlag liest sich überhaupt wie ein Plädoyer, die Schäden, die die nationalsozialistischen Eingriffe in der Musik- und Kunstausbildung hinterlassen hat, zu reparieren. „Die Jugend steht […] vielen Kunstwerken der letzten Jahre ratlos gegenüber“, so Petyrek, der „besonders Musikerzieher und Komponisten“ in die vergleichende Volksliedforschung einführen möchte (Abbildung 4). Petyreks Ideen scheinen visionär, er erwähnt die Schaffung eines Audioarchivs als „dringlichste Aufgabe“ und weist auf die künstlerisch-praktische Ausrichtung des Instituts hin, womit er einige der Entwicklungen vorwegnahm, die das 1965 gegründete Institut für Volksmusikforschung erst nach und nach verwirklichte.