At Austrian postsecondary institutions, recent months have seen teaching take place mostly online. So how has that worked out? What’s gone well, and what hasn’t? Here’s what members of the mdw teaching staff have to say.

While it had long been on the agenda, mid-March saw it happen from one week to the next: the digitisation of education. During the coronavirus lockdown, the mdw—like other institutions—transferred all of its teaching to the Internet. Which meant that attending a lecture more or less consisted of opening your laptop, clicking on a link to join a videoconference, and watching the lecture on your screen.

But what are the strong points and weak points of this form of teaching? And what potential does it offer for the future? mdw Magazine asked around among teaching staff members to get an impression of their experiences with digital teaching.

At first, said those with whom we talked, the switchover pitted them against technical challenges. They had to get familiar with the relevant tools—like Zoom, Skype, or the learning platform Moodle. “We learned a bunch of new skills at lightning speed,” said Michael Meixner of the Leonard Bernstein Department of Wind and Percussion Instruments.

Teaching methods had to be adapted, as well. Lots of things that would normally merit a quick explanation in class suddenly had to be formulated in writing. “The good thing about that is that you end up with well-conceived reading material. But it did sometimes feel like an obstacle,” Meixner recalled.

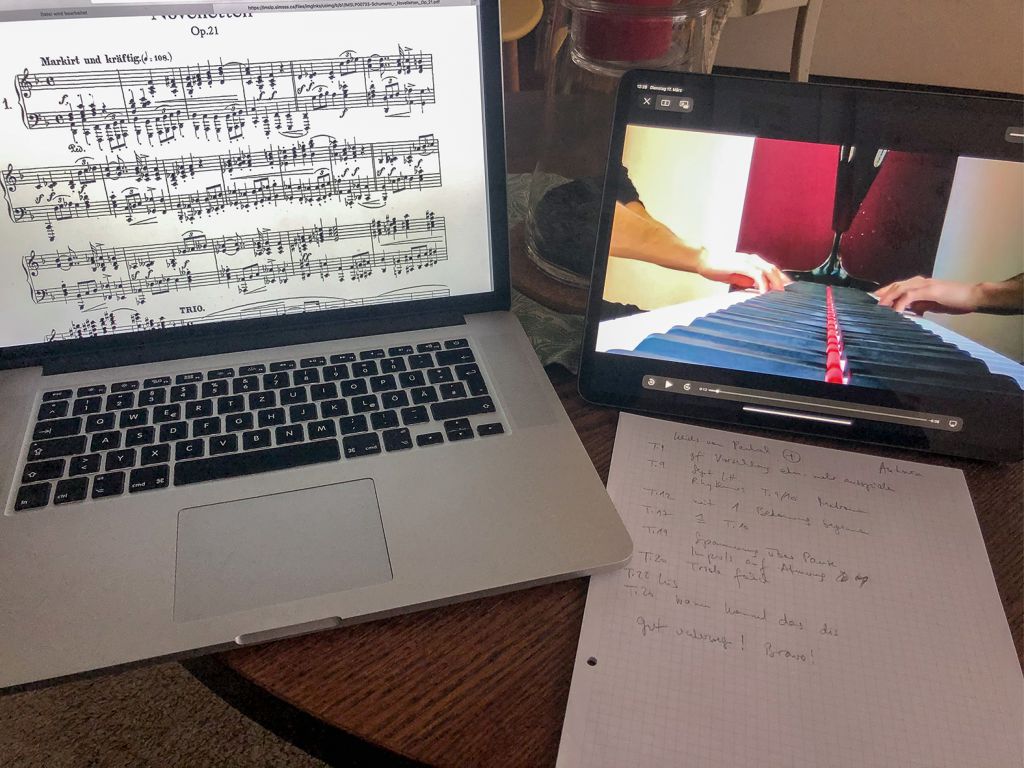

The need to radically change teaching methods was also mentioned by Elisabeth Aigner-Monarth, who teaches piano and piano didactics at the Ludwig van Beethoven Department. “What I tried to do was to go beyond frontal presentation of the material via Zoom in order to actively involve students in this special setting, as well.” Like other teachers, Aigner-Monarth employed pre-produced videos. For one thing, she provided students with piano didactics videos that showed examples of teaching situations to be analysed. And in her individual artistic instruction, she asked her students to make and send to her videos of their own piano-playing. Similar things happened in voice instruction at the Antonio Salieri Department of Vocal Studies and Vocal Research in Music Education, said department head Judith Kopecky. In addition to regularly scheduled video conferences, students recorded their practising—and their teachers provided them with feedback.

“What we needed were creative approaches to problem-solving, and those brought forth new things,” said Magdalena Fürnkranz, who teaches at the Department of Popular Music. One of these things, she said, was a podcast that arose during an ipop course.

A disadvantage pointed out by our interviewees was that digital teaching requires a lot more effort from both students and teachers. But they could also make out positive aspects. By filming themselves while practising, for example, students had a chance to school their critical and self-observation skills while also becoming more independent. What’s more, this form of teaching offered a high degree of flexibility: “The fact that it lets us all learn and teach independent of time and space is something I find particularly attractive,” said Fürnkranz. Another plus was that communication functioned very well during the crisis. It seemed to be the case that for the students, their studies represented a sort of anchor during this period, observed Florian Reiners, professor of lead voice and speech at the Max Reinhardt Seminar. “Many of them went home to their parents and were thrown back into their old lives.” So their online coursework, he said, provided continuity and was followed “with a great deal of concentration”.

All of our interviewees agreed that digital teaching, despite all its advantages, simply can’t replace teaching in person. “When it’s theatre you’re doing, you need an audience and tension in the space around you. This is something that was all the more clear to us after nine weeks on Zoom,” said Reiners. And in June, when it became possible to resume some teaching at the University subject to the necessary safety measures, everyone was happy: “We breathed a huge sigh of relief.” They all agreed that people who work in the cultural field need interaction. As Aigner-Monarth put it, “When it comes to art, in-person encounters just can’t be replaced.”

“The energy of the group, interpersonal aspects, spontaneity, and non-verbal communication” all suffer in digital teaching, explained Film Academy Vienna head Sandra Bohle. So for her and her colleagues, working together at the University is essential.

It’s most likely the case that the future lies in a combination of both forms of teaching. “Lectures whose content changes very little over time can be recorded and regularly updated to reflect new findings and content,” opined Fürnkranz. Meixner can imagine theory being taught online and practice being taught at the University: “Well-prepared digital content permits the kind of repetition and greater depth that often fall by the wayside in live, seminar-room teaching. And conversely, you can be free to emphasise practical application when teaching in person if the ‘facts’ have already been clarified in videos.” But for this, he says, the mdw needs more spaces equipped with the right technology “in order to ease the production of videos and other well-conceived teaching materials.”

Aigner-Monarth joins in the call for good technical infrastructure: “At the moment, we’re having to rely on our own tools.” And not everybody, after all, has a brand-new computer and a fast Internet connection at home. It’s also frequently the case that students’ instruments leave much to be desired: “One of my students practices on an upright piano in a dormitory basement room where the acoustic is way too wet.” And Bohle, of the Film Academy, told us that online teaching proved difficult in certain majors there: “Teaching montage without an editing room and teaching camera without equipment can only be done in a very skeletal way.”

For academic teaching, added Fürnkranz, there needs to be better access to digital resources—specifically “more licences for online archives, selected specialist journals, and scholarly E-books.” She also pointed out a need “to support learning processes in digital teaching, as well.” And in general, everyone we asked mentioned a need to strengthen the media skills of both students and teachers.

All of our interviewees were asked about their general takeaways from the past few months. And for Kopecky, it was “the courage to rethink things”: she’s now looking forward to developing innovative teaching methods—albeit “before the roof’s on fire”, and with the necessary time to think it all through.