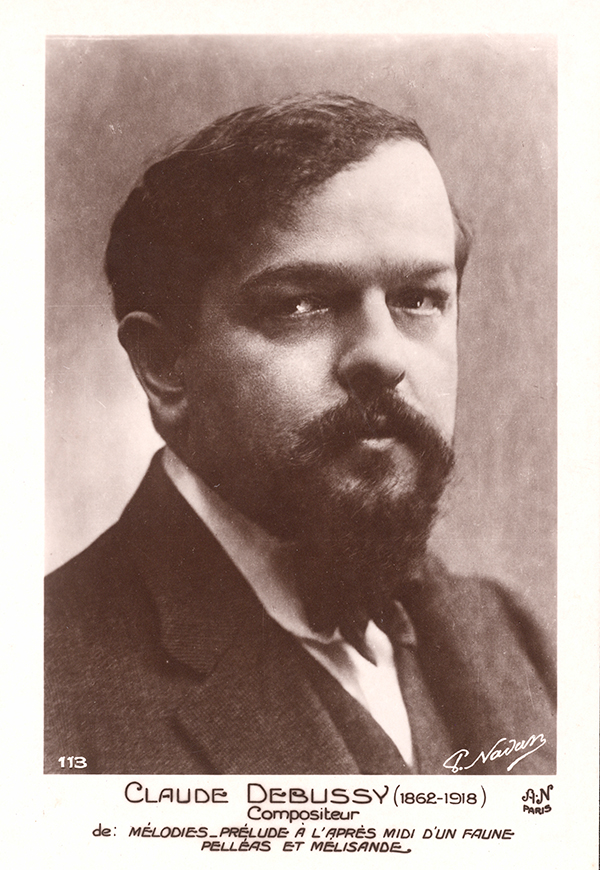

On 25 March, it will have been 100 years since Claude Debussy’s passing—reason enough to give some extra thought to his music. Opinions on his works’ status in today’s musical life are unanimous: the Prélude à l’aprés-midi d’un faune and La Mer are fixtures in numerous orchestras’ repertoires, works like Syrinx for flute and the Préludes for piano are regulars on solo recital programmes, and the opera Pelléas et Mélisande, which Claudio Abbado realised in an exemplary fashion nearly 30 years ago in Vienna, was heard once again last year at the Vienna State Opera. In light of such popularity, it’s easy to forget that Debussy’s oeuvre was controversial beyond just his lifetime.

Debussy’s controversiality goes back quite a long way. The composer’s consistently anti-academic stance earned him the reputation of a rebel and a free spirit quite early on, with contemporaries like his colleague Jules Massenet coining the formula of the “enigmatic Debussy” (“Debussy, c’est l’enigme”). And even after 1910, by which time the composer was already known Europe-wide, this hardly changed—since especially his late oeuvre was considered difficult to understand. Works such as Jeux (1913) drew sceptical comments even from well-meaning commentators: Léon Vallas (one of the first Debussy biographers) opined that the master had “thrown the rules of composition overboard” in this piece, and even as late as the 1970s, Albert Jakobik referred to Jeux as an “unanalysable” piece of music.

One can discern a basic tension here that, in principle, can still be felt today: works like the Prélude à l’aprés-midi d’un faune, beloved of musicians and audiences alike, are hard to analyse musically. The difficulty inherent in going from a work’s immediate effect to reflection on its overall concept is present in any music, but in Debussy’s case, it would seem to be more severe. To what can this be attributed?

We can only get to the bottom of this question if we take a look at the central importance of tone colour in Debussy’s music. And to this end, the beginning of the Prélude à l’aprés-midi d’un faune can serve as an example. After the opening flute arabesque, one hears a seventh chord over B that would traditionally need to be resolved in keeping with major-minor tonal functional harmony. But it never does get resolved. The chord is instead sustained until it gives way to a rest. For the way in which music was heard, this entailed no less than a revolution. Jean-Luc Nancy, who wrote the wonderful book Listening (original title: À l’écoute), might express it this way: instead of hearing the chord, we “listen” to it. This brings out its colours, aided by Debussy’s novel art of instrumentation. So it’s no coincidence that we perceive a “new breath” in this music, as Pierre Boulez so fittingly put it.

All this entailed immense challenges for musicology, since it was only comparatively late that tone colour began to be theoretically addressed. The term “tone colour” only came to be used in German (as Klangfarbe) during the 1920s, in fact, and the technical means by which to examine the structure of tone colour from the inside have really only been developed over the past ca. 50 years. The phenomenon of tone colour (from the French “timbre”, as which it is also known in English) is networked and multidimensional. This renders isolated, individual observations obsolete, for tone colour is truly an all-encompassing phenomenon.

In the absence of adequate tools with which to describe tone colour as a concept, one often spoke vaguely and in a fairly generalised fashion of Debussy’s “impressionism” and of tonal hues flowing into one another, along with the supposedly “static” nature of his music. All this invites misunderstandings. Those who embark upon the fascinating journey of scrutinising this music’s sonic qualities more or less under an “acoustic magnifying glass” will notice just how exactingly Debussy employed various hues: his sonorities are, in fact, anything but vague. And talk of this music’s “static” or “non-functional” nature can likewise be misleading, since not only motifs and themes, but also the sounds themselves are capable of undergoing development.

Debussy’s works had a lasting effect on music composed after 1945—one need only think of the quality of silence woven through these sounds, or of the potential to suggest proximity and distance. But even so, one shouldn’t characterise this as being unique: for the young Webern, as well (who deeply admired Debussy), the paradigmatic elements of sound, silence, and space were possessed of central relevance. The fact that this was at first overlooked was due to more than just musical factors: prior to and during the First World War, both the Second Viennese School composers and Debussy himself were afflicted with the sort of chauvinism that was practically universal at the time. 1914 saw Debussy speak of barbarie allemande and his aversion to both Strauss and Schönberg in the same breath, while Schönberg, for his part, repeatedly asserted the superiority of German-Austrian music.

These days—at least in the cultural sphere—such nationalism has become obsolete, and the practical and theoretical doors are wide open to a genuine and substantive dialogue between musical cultures. In France as well as in the German-speaking and Anglo-American worlds, the intensity of research work on Debussy—including formal and structural analysis, as well as research on interpretation and historically informed performance—has increased. And the events now planned to mark the 100th anniversary of Debussy’s passing will surely prove once more that a music that confronts us with mysteries can indeed be the subject of theoretical reflection. It was fully in this spirit that Vladimir Jankélévitch (who, as a mediator between philosophy and musicology in France, assumed a position roughly equivalent to that of Adorno in Germany, and whose work is now being rediscovered in the German-speaking world), wrote the following: “Whereas all secrets require complication and profundity, Debussy is intelligible because his mysteries are clear. Debussy is mysterious, but he is clear.”

Event Tip

Thursday, 26 April 2018, 7.00 pm

Une Nuit Mythique pour le Centenaire de Claude Debussy

mdw students perform solo and chamber works in the context and presence of masterpieces at the Austrian National Gallery

Oberes Belvedere

Prinz-Eugen-Straße 27

1030 Vienna