A central performance practice-related concern is the employment of period instruments or appropriately made replicas thereof, the investigation and mastery of which brings us closer to the music created by those who originally played on them. For musicians today, this entails constant study of objects from both private and public collections and sources both pictorial and written, as well as close collaboration with instrument makers, curators, restorers, and other researchers in this field.

Institutions like the mdw play an important role in this process, with our university’s long history having given rise to an impressive collection of historical instruments. Numerous originals and replicas have been acquired, ranging from a 17th-century chalumeau to a Biedermeier-period Viennese fortepiano, and these instruments are available to all students who seek to learn more about this field.

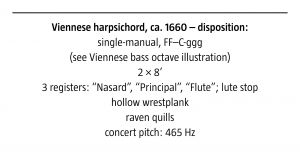

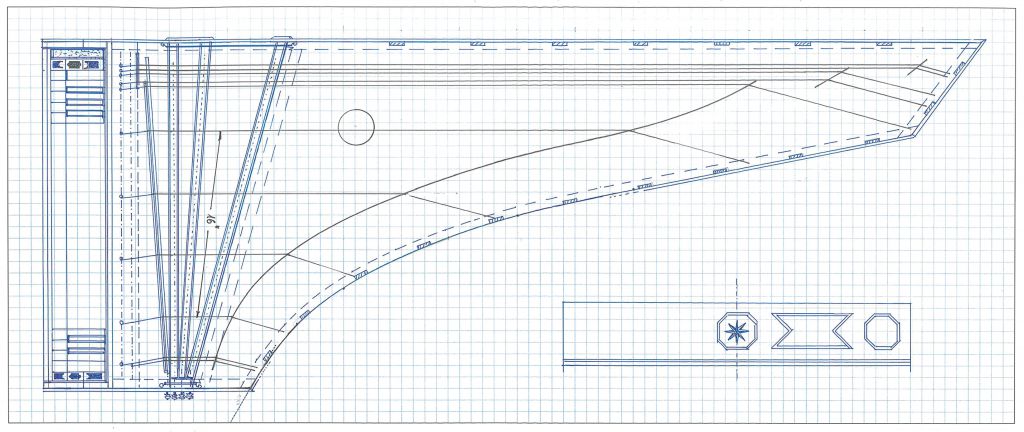

A special category within this collection is represented by the harpsichords. Over the many centuries of its existence, the harpsichord has taken on a wide variety of forms—and in order to do justice to this diversity, the mdw is constantly looking to expand and update its holdings. An important contribution to these efforts is the project The “Viennese Harpsichord” in a Historical Context initiated in 2017 by Ingomar Rainer, who occupied the mdw’s professorial chair in Historical Musical Practice. This project’s primary aim was to reconstruct a harpsichord that no longer existed, of a type that might have been typical of Viennese harpsichord-building around 1660.

What’s more, this main object was complemented by the acquisition of four additional harpsichords built after various examples that show the influences on and effects of Viennese-style harpsichords in Europe in different ways. The project, completed in 2020, was made possible by a 2017 grant from the University Infrastructure Programme of the Vienna Science and Technology Fund (WWFT).

Alfons Huber, then restoration workshop head at the Collection of Historic Instruments of the Kunsthistorisches Museum (KHM) in Vienna, joined forces with historical keyboard instrument specialist Albrecht Czernin to take on the main commission: to construct a hypothetical harpsichord of a type that might have been used during the second half of the 17th century at the Viennese court or by one of the important musical establishments maintained by members of Austria’s high nobility.

In order to complete this rather unsolvable puzzle in the best possible way, Huber first set about carefully compiling a set of structural characteristics. And in an uncompromising manner, he and Albrecht Czernin then attempted to recreate both the sound of such an instrument and the overall impression that it might have made.

It was in April 2020, following months of hard work in Albrecht Czernin’s workshop, that this instrument was delivered. And as a brief glimpse into the research process behind it, the following describes two conspicuous and exemplary characteristics:

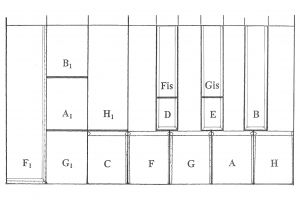

The Viennese bass octave

The bass-end of this instrument’s keyboard will surely appear strange to uninitiated eyes, for the ordering of the keys—some of which exhibit multiple splits—is in fact unique in music history.

The oldest known documentation of the so-called Viennese bass octave can be found in Alessandro Poglietti’s Compendium, written in Kremsmünster in 1676. During the 16th and 17th centuries, short octaves were the norm: since certain low notes (F#, G#) were hardly ever used, they were eliminated to save space, a change that involved replacing the first E-key with C, F# with D, and G# with E. Over the course of time, an expansion on this pattern became common: two keys at the upper end, D/F# and E/G#, were likewise “divided”. The Viennese bass octave, however, went one step farther by adding additional low notes (F<sub>1</sub>, G<sub>1</sub>, A<sub>1</sub>, B<sub>1</sub>, H<sub>1</sub>) that were to be played via a highly original combination of split keys, the first of which (F<sub>1</sub>) was often given the appearance of a keyblock.

Playable instruments from this period with such a wide compass are now extremely rare, so our reconstruction makes an important contribution to filling this gap in how the history of Viennese keyboard instruments can be experienced.

Decoration

Pragmatic considerations entail that it’s rarely possible these days for newly built harpsichords to reflect the original magnificence of historical examples. But in order to still have a chance at experiencing a semblance of such an instrument’s overall effect on its player and the listeners, we did try to give special consideration to this instrument’s outward appearance. In order to lend it a certain courtly character, elaborate veneering, inlays of exotic woods, and an eye-catchingly lively exterior finish were employed. The recipe for this finish was adapted from the Ars Vitraria Experimentalis by Johann Kunkel (Frankfurt/Leipzig 1689):

A fine way/of adding a speckled finish to the Clave Cord and Clave Cimbeln as well as other works of carpentry. First, dip your work in glue/and thereafter paint it a couple times with distemper/and when well-dried/speckle it as you like with flaked white lead/mixed with thinned glue/and when entirely dry/take verdigris1 rubbed off with oil/and use this to overpaint your piece multiple times/to render the white spots green/and permanent.

This special harpsichord enables us not only to study the entire Austrian harpsichord repertoire of the 17th century as it was played at the courts of emperors from Ferdinand II to Joseph I and by the music establishments of the great noble houses, but also to enter new realms of ensemble sound—accompanying us in the truest sense and supporting our explorations together as we develop our new department.