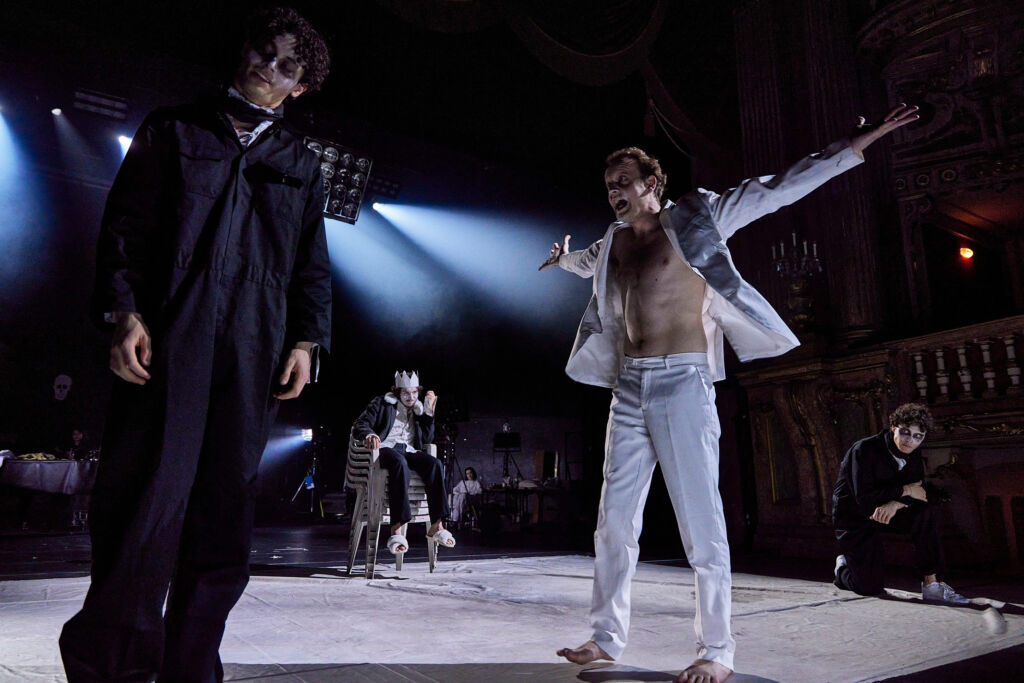

Der isländische Opern- und Theaterregisseur Thorleifur Örn Arnarsson widmete sich mit den Schauspielstudierenden des dritten Jahrgangs am Max Reinhardt Seminar einer der größten Theater-Tragödien aller Zeiten: Shakespeares Macbeth. Im Interview mit dem mdw-Magazin erzählt er von den Freuden der Arbeit mit einer neuen Schauspieler_innen-Generation, welche Ansprüche er an seine Rolle als Gastlehrender am Max Reinhardt Seminar hat und warum Shakespeares Macht- und Menschheitsanalysen alle Zeiten überdauern.

Es wirbelt am Max Reinhardt Seminar: Junge Studierende durch Gänge und Stiegenhäuser, sattgrüne Blätter über den pittoresken Vorplatz und die nachmittägliche Mai-Sonne über die holzvertäfelten Wände. Quer durch das bunte Treiben hindurchgewunden, findet man sich plötzlich in einem großen, weiten Raum wieder. Auch hier wieder: romantische Botanik und edle Holzverkleidung. Doch plötzlich und auch unerwartet: Stille. Mittendrin sitzt Thorleifur Örn Arnarsson. Der isländische Opern- und Theaterregisseur wurde im Sommersemester 2025 an das Max Reinhardt Seminar berufen, um mit dem dritten Jahrgang der Schauspielstudierenden die Jahresaufführung zu erarbeiten. In seiner temporären Wirkungsstätte treffen wir ihn aus diesem Anlass zum Interview.

Für seine Arbeit mit den Max-Reinhardt-Seminar-Studierenden konnte sich Arnarsson eines Stoffes bedienen, der ihm durch seine langjährige und intensive Auseinandersetzung damit zutiefst vertraut ist: Shakespeares Macbeth. „Ich wollte den Studierenden ein Stück anbieten, das anspruchsvoll ist, mit dem sie aber auch ringen müssen, und das gleichzeitig, glaube ich, ein Einblick in die Seele unserer Zeit ist.“ Bereits auf zahlreichen namhaften Bühnen hat der in Reykjavík geborene Regisseur, der Schauspiel an der Kunstakademie Island und Regie an der Hochschule für Schauspielkunst Ernst Busch in Berlin studierte, diesen größten aller englischen Dramatiker_innen inszeniert: „Weil er einfach der Beste ist. Er schreibt genau zu der Zeit, in der sich das ‚Ich‘ entwickelt hat. Shakespeare hat mehr als vielleicht jeder andere Autor das Selbstbild des modernen Menschen bestimmt – Shakespeare und die Griechen. Und jede Figur bei Shakespeare ist ein Universum für sich.“

Warum es gerade für die jungen Studierenden des dritten Jahrgangs geeignet ist? Anspruchsvolle Texte, mit denen man sich auch intensiv beschäftigen müsse, wo man aber auch ins Spiel miteinander komme und mit einer Theaterform konfrontiert sei – das träfe laut Arnarsson die Bedürfnisse junger Schauspieler_innen am Anfang ihrer Karriere ziemlich gut. „Was Macbeth so toll beschreibt, sind die Mechanismen der Macht. Ich finde, da ist Shakespeare mit seiner Machtanalyse schlichtweg kaum zu übertreffen, indem er darstellt, was es aus der menschlichen Perspektive dazu braucht – was du opfern musst, was du aufgeben musst –, um an die Spitze zu kommen.“

Für Thorleifur Örn Arnarsson ist die Arbeit am Max Reinhardt Seminar eine willkommene Gelegenheit, seine jahrzehntelange Erfahrung als Theaterregisseur, unter anderem am Wiener Burgtheater, an der Volksbühne Berlin und an zahlreichen anderen hochrangigen Häusern, mit jungen Talenten zu teilen. „Für einen Regisseur ist es toll, einer neuen Generation und auch ihrer Sprache und ihrer Herangehensweise näher zu kommen. Ein Teil dessen, warum es interessant ist, mit Studierenden zu arbeiten, ist eben auch zu sehen, wie sie sich ihrer Kunst annähern, individuell wie auch kollektiv. Ich wollte sehen: Was halten sie von dem Stoff, was halten sie von diesen Ideen?“ Die Arbeit an Macbeth beinhaltete nicht nur die rein szenische Erarbeitung des Stücks, sondern erfolgte auch interdisziplinär: Die Studierenden erhielten einen Kostüm-Workshop mit dem Bühnen- und Kostümbildner sowie Musik-Workshops, die in die Performance miteinfließen sollten. Arnarsson und die Studierenden haben sich in einem kollaborativen „Laboratorium“ wiedergefunden, in dem das Prinzip „Making by Doing“ vorherrschte. „Vor allem ist es auch einfach Reibung. Die sind nicht nur talentiert, sie sind auch total mutig. Auch was die Form angeht, sind sie so aufgeschlossen und offen, was total Spaß macht“, attestiert der Regisseur den Studierenden.

„Ich kann mich sehr gut an die Zeit erinnern, als ich selbst Student war. Und das ist, glaube ich, das Problem für fast jeden, der an einer Kunstschule studiert: Du bist zugleich Student und Künstler, das ist teilweise total schwierig.“ Daher sehe er es jetzt auch als seine Aufgabe als Lehrender, dass die Studierenden auch wahrhaftig erleben, wie ein wirklicher Inszenierungsprozess sei, „der teilweise auch brutal ist. Da sterben Ideen, Texte werden gestrichen oder umverteilt, und das ist eine ziemlich brutale Maschine.“ Das hieße längst nicht, dass man dabei unsensibel sein müsse, aber: „Kunst machen ist eben kein Spaziergang in der Sonne.“ Vor allem mit einem so dunklen Stoff wie Macbeth. Ein wesentliches Anliegen sei dem Regisseur in der Theaterarbeit mit den Studierenden auch, dass sie lernen, dass sie als Schauspieler_innen ihre eigene Welt mitbringen müssen „und diese auch zur Verfügung stellen“. Auch was sie persönlich über den Text oder das Stück denken, solle in der Performance einen wichtigen Platz erhalten.

Ob und wie man das mehr als 400 Jahre alte Stück in das Jahr 2025 übersetzen könne, ist für den Regisseur eine rhetorische Frage. „Wir haben ja als Menschen die Fähigkeit, unsere eigene Wirklichkeit abzulegen, unsere Welt zu verlassen: Wir setzen uns in ein ritualistisches Setting wie den Zuschauerraum, das Licht geht an, wir sehen eine andere Wirklichkeit. Aber meine tatsächliche Wirklichkeit ist ja deshalb nicht verschwunden. Kinder nehmen Theater zum Beispiel eins zu eins auf. Irgendwann entwickeln wir – als einzige Spezies – doch diese unfassbare Fähigkeit, mehrere Wirklichkeiten in uns gleichzeitig tragen zu können.“ Daher möchte Arnarsson davon absehen, einen Theaterabend in eine spezifische Zeit zu setzen. „Das ist für mich immer ein bisschen problematisch, weil das der Raum ist, wo man frei denken kann.“ Theater sei eben auch der Ort der Fantasie.

Da Kunst der Ort der freien Gedanken ist, ist auch Österreich und spezifisch Wien für Arnarsson ein lebens- und liebenswerter Fleck Erde. „Diese Stadt ist durchdrungen von Kultur. Kunst ist, wie man merkt, eine zentrale Säule ihrer Identität. Das siehst du weder in Berlin noch in Island.“ „In diesen hochkapitalisierten, individualisierten Zeiten, wo es immer mehr darum geht, ins Entertainment zu flüchten, weg von der Welt, habe ich den Eindruck, dass dieses tiefe Verlangen und die Unterstützung der künstlerischen Welt und des künstlerischen Raums hier eine sehr große Anziehungskraft hat.“

Daher habe er sich von Anfang an in Österreich zu Hause gefühlt. Zwischen der isländischen und österreichischen Nationalseele gäbe es in seiner Wahrnehmung große Ähnlichkeiten: „Dieser unterläufige Humor, der doppelte Boden.“ Auch, dass man Dinge „von Mensch zu Mensch“ kläre, das fühle sich eben ähnlich wie in seinem kleinen Heimatland Island an, wo man auch schnell und direkt an Menschen herankomme.

Nach der Aufführung von Macbeth, die im Juni 2025 stattfand, geht es für die Studierenden im Herbst weiter mit ihrem Absolvent_innenvorspiel, wo sich der Abschlussjahrgang des Max Reinhardt Seminars Jahr für Jahr einem Fachpublikum präsentiert. Auch Thorleifur Örn Arnarsson wird nach Abschluss der Zusammenarbeit mit den Max-Reinhardt-Seminar-Studierenden wieder in Österreich anzutreffen sein. „Ich komme ja unfassbar gern nach Wien und bin mir auch sicher, dass das wieder passieren wird.“