The Vienna-born violinist and composer Fritz Kreisler (1875–1962) was one of the 20th century’s most influential recording artists, and this year marks the 150th anniversary of his birth. In past decades, several publications1 have focused on Kreisler and his contemporaries’ performance style—particularly the aspects of continuous vibrato and expressive portamento, which have been proven to have been (at least partly) a result of the “Phonograph Effect”2. But even though Kreisler received frequent praise for his rhythmic refinement3 and researchers have spontaneously taken his Liebesleid as illustrative examples, relatively little research has been devoted to the rhythmic characteristics of his performance style, especially the unequally distributed “Viennese Rhythm” in such waltz-like music.

What is “Viennese Rhythm”? And why Liebesleid?

In our recent work4, based on over 30 recordings of Johann Strauss II’s The Blue Danube, we confirmed a consistently recurring beat pattern in performances by Viennese orchestras, especially the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (VPO): the short–long–medium pattern. The probability of this “Viennese Rhythm”, with Beat 2 longer than Beat 3 longer than Beat 1 (B2>B3>B1), is significantly higher in VPO recordings (39%) than in non-VPO ones (18%). Coincidentally, one of Kreisler’s most performed and recorded pieces—Liebesleid, with its tempo marking of “Ländler” (a slower predecessor of the Viennese Waltz native to the southern German-speaking region)5—is the central movement of his Alt-Wiener Tanzweisen (Old Viennese Dances) and hence naturally becomes an ideal research focus.

Measured beat ratios in Kreisler’s own recordings

In the present study, we began by analysing Kreisler’s complete recordings of his Liebesleid by extracting the time codes of all (quarter) note onsets in the first phrase using the online performance analysis tool Vmus.net and found that the average beat ratios can be categorised into three groups:

- heavily unequal (HU, 1:1.44:1.22), in 1930 and 1938 with Franz Rupp as pianist.

- moderately unequal (MU, 1:1.28:1.16), in 1926 (takes 6 and 7) with Carl Lamson.

- nearly equal (NE, 1:1.05:1.08), in 1910 and 1912 with George Falkenstein, in 1911 with Haddon Squire, and in 1942 with conductor Charles O’Connell.

At first glance, these findings appear contradictory. Groups 1 and 2 conform more or less to the “Viennese Rhythm”, but group 3 is entirely different. Considering that the rhythmic pattern is determined mostly by the chords in the piano accompaniment, it becomes unclear whether Kreisler himself really intended to realise or not realise this “swing effect”. Fortunately, he was also an excellent pianist who even garnered praise from Ignacy Paderewski, who stated: “I’d be starving if Fritz had taken up the piano”6. Fortunately, there does exist a 1921 recording of Liebesleid with Fritz Kreisler at the piano accompanying his cellist-brother Hugo (Figure 1). The beat ratio of the first phrase there is 1:1.42:1.30, very close to group 1 (HU), which strongly suggests that Kreisler himself tended toward strongly pronounced “Viennese Rhythm”.

“Viennese Rhythm” as a cultural and/or historical practice

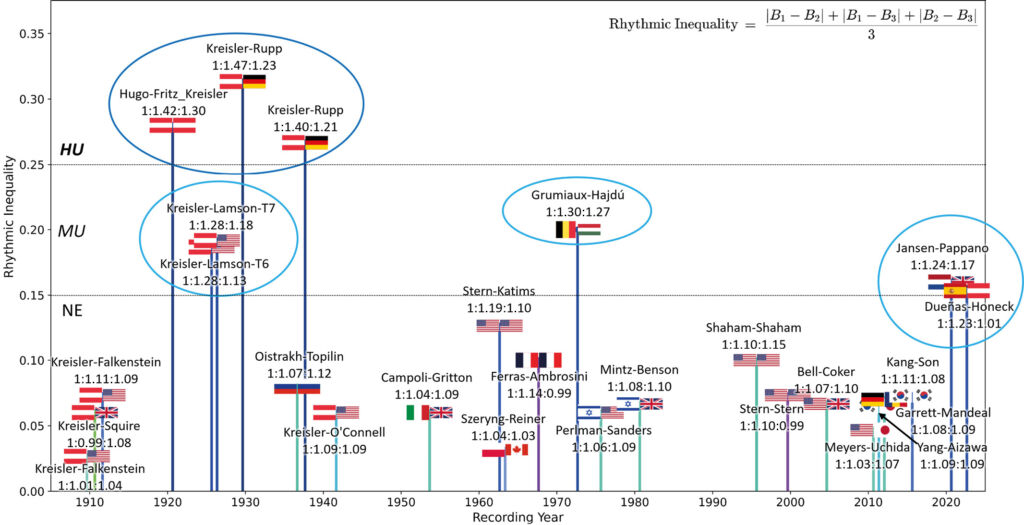

This initial finding also indicates that the pronouncedness of “Viennese Rhythm” in different stages of Kreisler’s career seems to have been strongly influenced by collaborators from different cultural backgrounds. In order to further investigate this issue, we compared further performances selected from the top ten most-viewed recordings on YouTube along with the top ten most-collected albums on Discogs. Discounting duplicates and arrangements for other instruments, we thus analysed the beat ratios of the first phrases in a further 17 performances and constructed a timeline reflecting the performers’ birth countries and their rhythmic inequality that encompasses all of the analysed recordings including Kreisler’s aforementioned nine (Figure 2).

From Figure 2, we can see that with the exception of Kreisler’s recordings with his brother Hugo and with the German pianist Rupp, the “Viennese Rhythm” is relatively more prominent in the 1973 recording by the Belgian violinist Arthur Grumiaux with pianist István Hajdú (who was born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire), in the 2021 recording by the Dutch violinist Janine Jansen and the English pianist/conductor Antonio Pappano (who worked in Germany for many years), and in the 2023 recording by the Austrian-trained Spanish violinist María Dueñas with the Austrian conductor Manfred Honeck conducting the Wiener Symphoniker, all of which have some direct or indirect relationship with Austrian-German musical culture. In contrast, the historical factor seems to be less significant. Kreisler’s earliest 1910 recording with pianist George Falkenstein, for example, has the least “Viennese Rhythm”, while the 1937 recording by David Oistrakh and Vselovod Topilin has far less rhythmic inequality than Kreisler’s own versions accompanied by Rupp from around the same time.

By how much do Liebesleid performances with and without “Viennese Rhythm” differ?

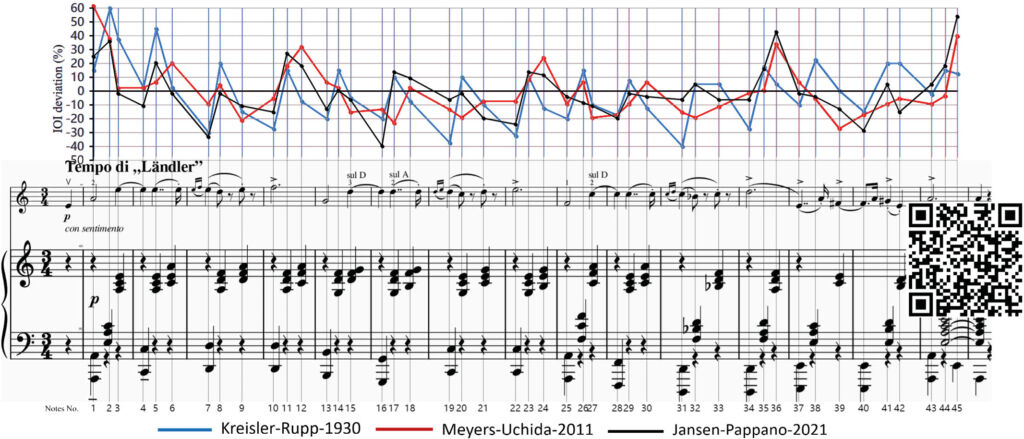

In short, the previous analysis reveals that modern recordings of Liebesleid with no direct personal connection to Austria or Germany generally involve less “Viennese Rhythm”, which makes a huge artistic difference. Figure 3 shows the inter-onset interval deviation curves of the recordings made by Kreisler-Rupp in 1930 (ranked #1 on YouTube, 1:1.47:1.23), Meyers-Uchida in 2011 (ranked #2 on YouTube, 1:1.03:1.07), and Jansen-Pappano in 2021 (among the most recent Top 10 on YouTube, 1:1.24:1.17). Contrary to Kreisler-Rupp’s exaggerated short-long-medium rhythmic pattern, Meyers-Uchida’s approach flows with silky smoothness—and the few notes significantly longer than the notated value (with an IOI deviation greater than 20%), e.g. No. 1, 12, 24, 36, 45, are all structurally contingent, which is typical in modern performances. In comparison, Jansen-Pappano seems to strike a balance between the Viennese rhythmic pattern and structural thinking, possibly influenced by their frequent engagement with Austrian-German musical traditions.

Generally speaking, modern musical performances tend to focus more on phrase-level structural aspects rather than bar-level rhythmic patterns. As a cultural and historical distinction, “Viennese Rhythm” may well be a common practice among Austrian-German musicians in the early 20th century. And it is most certainly among the essential characteristics of Fritz Kreisler’s unique performance style, which deserves further investigation in the future.

- Katz, M. (2006). “Portamento and the Phonograph Effect.” Journal of Musicological Research, 25(3-4), 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411890600860733

- Vollmer, F., & Bolles, B.-A. (2024). “In Search of the ‘Phonograph Effect’: Sonic Gestures in Violin Performance and Their Modification by Early Recording and Playback Devices (1901–1933)”. Music & Science, 7. https://doi.org/10.1177/20592043241226832

- Biancolli, A. (1998). Fritz Kreisler: Love’s Sorrow, Love’s Joy. Amadeus Press, 34.

- Zhou, D., & Yang, J. (2024). “Analysing Stylistic Differences between Orchestras: An Empirical Study of the ‘Viennese Rhythm’ in the Vienna Philharmonic’s Recordings of The Blue Danube”. Music Analysis, 43(2), 302–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/musa.12234

- Buurman, E. (2021). The Viennese Ballroom in the Age of Beethoven. Cambridge University Press, 46.

- Gruber, G. (Ed.). (2023). Fritz Kreisler: Ein Kosmopolit im Exil. Vom Wunderkind zum „König der Geiger“. Böhlau Wien, 33.