The total shutdown of public life that many countries imposed due to the Covid-19 pandemic has forced the closure of all musical event locations, from small music clubs to opera houses and on to sports stadiums where concerts are also held. What’s more, all concert tours run by the events promoters Live Nation, AEG, and CTS-Eventim have been either called off or postponed. And with that, not only have most musicians lost their most important source of income, but this crisis has also affected the music industry’s entire value-added chain—which, in the age of streaming, has become more networked than ever.

The cancellation of even just one major festival not only entails massive lost sales and negative employment effects but also does massive economic damage to the region where it would’ve taken place. By way of example: 2016 saw the six-day Coachella Music and Arts Festival draw around 100,000 visitors a day to Southern California’s Coachella Valley and generate economic activity worth of USD 704 million—of which USD 403 million remained in the region (Billboard 2020).

In Germany, the country’s various music industry associations have already undertaken an initial assessment of the damage done to the German music industry by the Covid-19 crisis, which they peg at EUR 5.46 billion. The lion’s share of this damage is to the music event sector, which is directly affected by public authorities’ ban on events and expected to suffer a EUR 4.54 billion loss over the coming six months (Verbände der deutschen Musikwirtschaft 2020).

Music Professionals’ Baseline Situation: Economic Precarity

What follows here is an attempt to roughly estimate the negative economic impacts on music professionals, and in order to do so, we must refer mainly to data from Germany. There is less data available that would be suited to making a similar assessment for the Austrian music industry, though research projects done prior to the current crisis do permit some conclusions. The study done by L&R Sozialforschung (2018), for example, shows that around 35 % of music professionals surveyed in 2017 lived in households that had low incomes and were thus at risk of impoverishment. Only 8 % lived in high-income households, while 59 % belonged to middle-income households (L&R Sozialforschung 2018: 81).1 Deeper analysis shows that for nearly half of the surveyed musicians, total annual income was less than EUR 15,000. Only 23 % indicated that they earned in excess of EUR 30,000 a year (ibid.: 71). And if one looks solely at income from artistic activities, the share of those music professionals whose earnings did not exceed EUR 15,000 rises to 86 %, with a mere 6 % of those surveyed earning more than EUR 30,000 (ibid.: 70).

Figures from Germany’s Künstlersozialkasse (KSK – Artists’ Social Security Fund) (KSK 2018) provide similar documentation of the precarious economic and social plight of music professionals among our neighbours. In 2018, 53,436 music professionals living in Germany were obligated to insure themselves through this fund due to having more than EUR 3,900 of annual income from freelance artistic activities as defined by § 3 (1) of Germany’s Artists’ Social Security Act (KSVG)2, and among this group, the average annual income as of 1 January 2019 was EUR 14,628 (men: EUR 16,241; women: EUR 12,222).

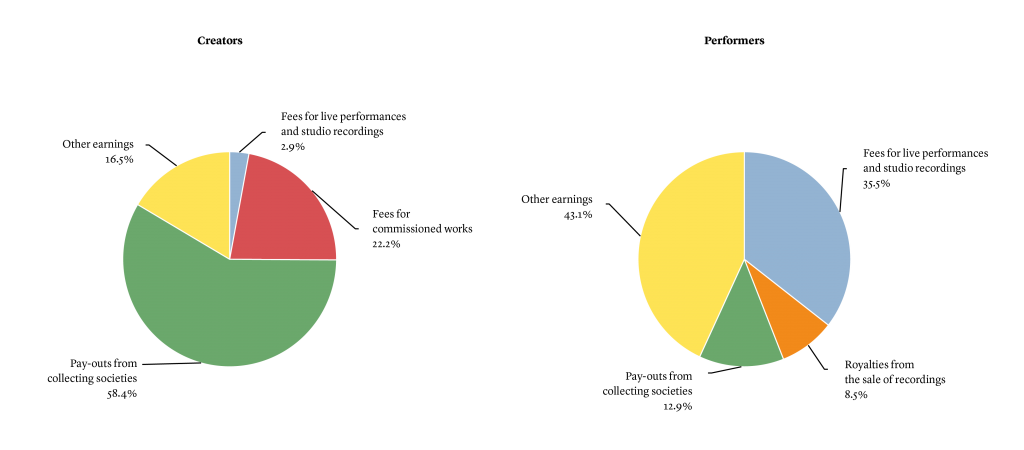

Here, one does need to consider the fact that the KSK does not represent all music professionals—only those who earn more than EUR 3,900 annually through their artistic activities. And a distinction also needs to be made between creators (composers, lyricists, arrangers), who make their living primarily from the creation of musical works, and performing musicians (conductors, instrumentalists, singers, choir directors, and DJs), who interpret music. But even if this distinction is a blurry one, with both activities often engaged in simultaneously, one usually can make out a main focus in terms of income. A study on music economics that investigated the situation in Germany (Seufert et al. 2015) ascertained that the share of performing musicians was 83.2 % while the creators accounted for 16.8 %; for the purpose of compiling these figures, individuals who engaged in mixed forms of work (e.g. singer-songwriter) were categorised according to their main source of income. Since the share of performing musicians in these figures is very high, it has to be assumed that the vast majority of these music professionals—altogether 44,455 individuals as of 1 January 2019—earned almost no income during the shutdown of all music-related events due to Covid-19. The German music economics study also allows one to discern income mixes.

Since collecting societies’ pay-outs are always based on the previous period, this source of income doesn’t dry up immediately. For this reason, the Covid-19 crisis will hit creators with a delay as royalty pay-outs for performances of their music drop sharply. The situation is similar with royalties from the sale of recordings and printed music, pay-outs of which also continue for a certain time. Due to social distancing rules, however, 2020 will also see less music productions taking place—and streaming behaviour has likewise changed during the Covid-19 lockdown: currently, traditional media are seeing more use than streaming services are (see Midia Research 2020).

The average income mix here, however, is not representative of the overall group of respondents. What’s more, the turnover statistics gathered by the German music economics study (Seufert et al. 2015: 23) found that only 250 music groups (ensembles, orchestras, choirs, bands, etc.) earned more than EUR 100,000 annually. A further 1,250 music groups had annual turnovers of between EUR 17,500 and EUR 100,000. Moreover, 2014 saw around one third of creators (2,750 individuals) earn more than EUR 17,500 for the year, while 600 even earned in excess of EUR 100,000. This allows one to conclude that income distribution among both creators and performers is highly uneven. And members of the latter group depend above all on performing fees, for which reason they will end up being hit particularly hard by the Covid-19 shutdown. At present, they have not only virtually no income but also no reserves on which they could draw, which puts them in severe danger of impoverishment.

Impact of the Covid-19 Crisis

How high, then, are the cumulative income losses among music professionals in Germany? If one uses the data provided by the Künstlersozialkasse for 2019 and assumes 53,436 music professionals obliged to ensure themselves as such who earn an average of EUR 14,628, one arrives at an annual production value of EUR 782 million for all music professionals thus documented. If one assumes the same income distribution between creators and performing musicians as in 2014 (44.3 % to 55.7 %), then an annual EUR 346.3 million per year went to the creators while EUR 435.4 million went to the performers.

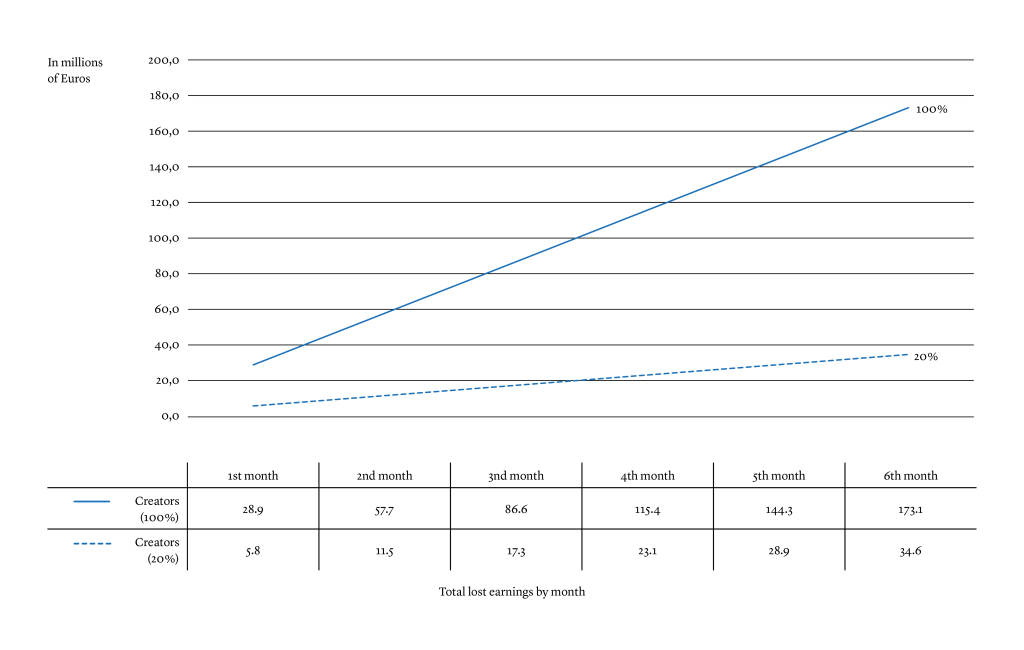

If 100 % of all the creators’ proceeds were to disappear, the cumulative income loss over a shutdown of three months’ duration would total EUR 86.6 million. And if the situation were to last half year, the losses would rise to EUR 173.1 million. For this group, however, pay-outs from the collecting societies represent the most important money-maker, and composing commissions for advertising and audiovisual media (which also play a certain role) would likewise continue for a little while longer. A low-end estimate of the income losses suffered by the creators might therefore be 20 %. In this case, their losses would total EUR 17.3 million over a three-month shutdown, while six months would entail losses of EUR 34.6 million.

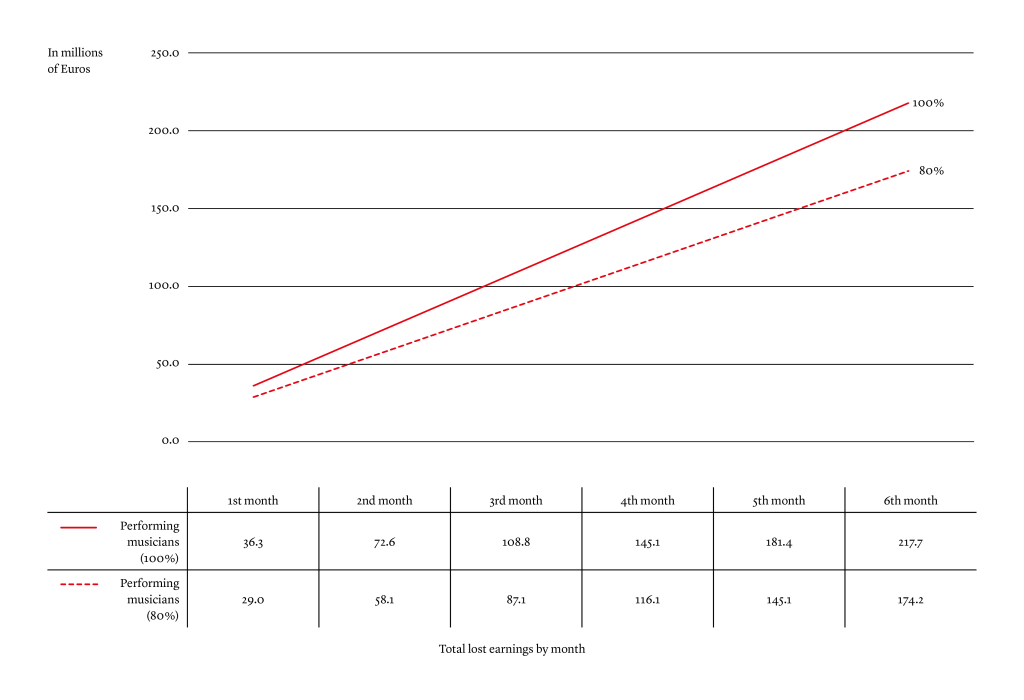

The situation of performing musicians is considerably more precarious. If all income were to disappear for three months, this would correspond to EUR 108.8 million, with losses for half a year totalling EUR 217.7 million. And even in the best-case scenario, this group would have to reckon with income losses of at least 80 %. The low-end figure for losses over three months would thus be EUR 87.1 million, with six months coming to EUR 174.2 million.

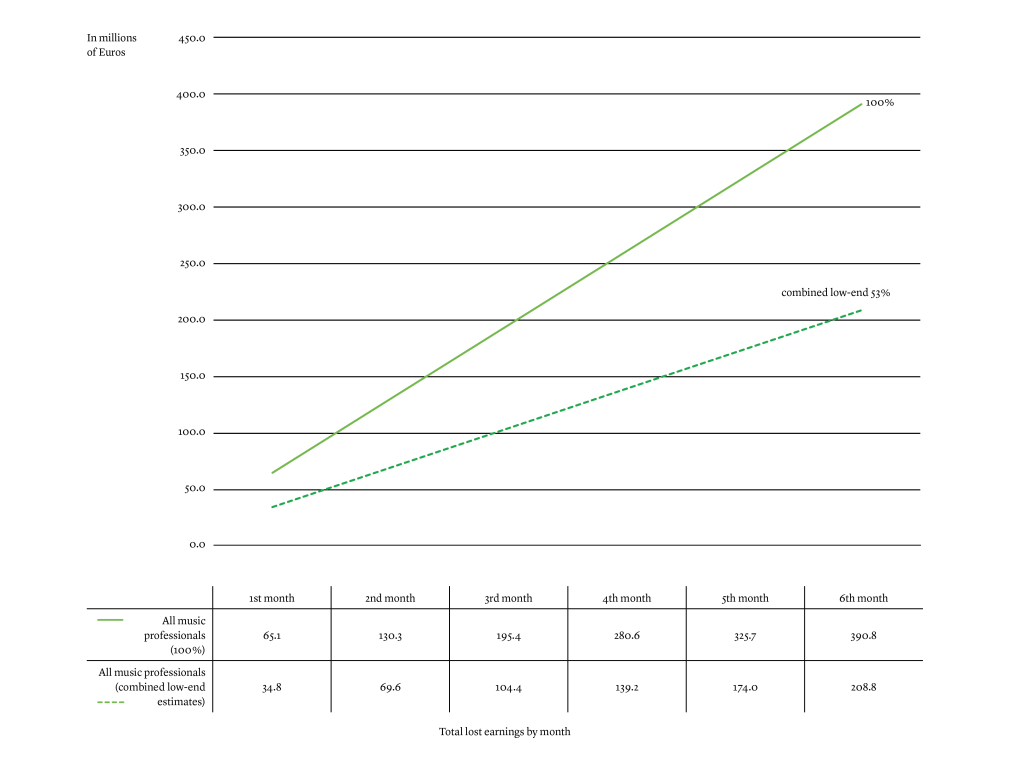

Collectively, a three-month event ban can be expected to hit music professionals in Germany with income losses of between EUR 100 million (optimistic projection) and in excess of EUR 200 million. And if the Covid-19 crisis were to last half a year, these losses would double to between EUR 200 million and EUR 400 million. The strongest immediate impact would be felt by the performing musicians, who had low incomes to begin with and were already at risk of impoverishment prior to the crisis. It is therefore above all this group that now needs swift, non-bureaucratic, and generous financial support from public sources.

Even now, one can already say that the Covid-19 crisis represents the most serious economic and social catastrophe for the cultural sector in general and for music professionals in particular since the end of World War II. And in addition to the financial assistance that has become necessary, a clear timeline will be needed for the step-by-step reinstatement of music events. Music theatre productions and events like major festivals and concert tours often require multiple years of preparation, and in this light, obtaining the degree of certainty necessary for planning will be essential. But due to how the music event business is internationally networked, precisely this certainty is currently missing due to stay-at-home orders and travel restrictions. So alongside national efforts to work out timelines for restarting music events, an increased degree of international cooperation will also be required in order to mitigate lasting damage to the live music business and to the music professionals who depend on it financially.

Sources:Billboard, 2020, “AEG & Live Nation Recommend Halting All Tours”, 12 March 2020, https://www.billboard.com/articles/business/touring/9333998/aeg-live-nation-recommend-halting-all-tours (accessed on: 22 Apr. 2020).

Künstlersozialkasse (KSK), undated, KSK in Zahlen: https://www.kuenstlersozialkasse.de/service/ksk-in-zahlen.html (accessed on: 22 Apr. 2020).

L&R Sozialforschung, 2018, Soziale Lage der Kunstschaffenden und Kunst- und Kulturvermittler/innen in Österreich. Ein Update der Studie “Zur sozialen Lage der Künstler und Künstlerinnen in Österreich”, 2008. Study conducted in collaboration with Österreichische Kulturdokumentation – Internationales Archiv für Kulturanalysen in response to a commission by the Austrian Federal Chancellery – Arts and Culture Division, Vienna.

Midia Research, 2020, COVID-19 | Recessionary Impacts and Consumer Behaviour. Study conducted by Mark Mulligan and Karol Severin, March 2020, London.

Seufert Wolfgang, Robert Schlegel und Felix Sattelberger, 2015, Musikwirtschaft in Deutschland. Studie zur volkswirtschaftlichen Bedeutung von Musikunternehmen unter Berücksichtigung aller Teilsektoren und Ausstrahlungseffekte. Published by Bundesverband Musikindustrie, Bundesverband der Veranstaltungswirtschaft, Deutscher Musikverleger-Verband, Europäischer Verband der Veranstaltungs-Centren, GVL, Live-Musik-Kommission, Society of Music Merchants, Verband der Deutschen Konzertdirektoren, and VUT. Berlin.

Verbände der deutschen Musikwirtschaft, 2020, Bericht der Verbände der deutschen Musikwirtschaft zu den wirtschaftlichen Auswirkungen der Corona-Pandemie, Berlin, 25 March 2020.

- “Low income” households are defined as those whose equivalised monthly household income is less than 60 % of the median value—a cut-off figure that currently equals approximately EUR 800. This group can be considered at risk of poverty.

- KSVK = Gesetz über die Sozialversicherung der selbständigen Künstler und Publizisten [Act on the Social Insurance of Freelance Artists and Journalists (Artists’ Social Security Act)] of 27 July 1981 (Federal Law Gazette [BGBl.] I, p. 705) in the currently valid version.