Franz Kafka’s close confidant Max Brod is said to have coined the oft-quoted saying according to which Prague was one hundred percent Czech, one hundred percent Jewish, and one hundred percent German. This paradoxical ascription points to the complex cultural makeup of Bohemia’s capital city, where ethnic, linguistic, and religious affiliations existed not distinctly side-by-side but as a dense web of relationships. The Prague of that era stood alongside Vienna as an important cultural centre of the Habsburg Monarchy in which imperial, national, and transnational influences overlapped.

An emblematic example of this multilayered character is the building that houses the present-day Státní opera [State Opera], opened in 1888 as the Neues Deutsches Theater [New German Theatre]. Up to the break represented by 1938, it functioned as a locus of both aesthetic modernism and processes of transnational cultural exchange. It was a place where an ambitious, programmatically contemporary repertoire could blossom—especially under the leadership of Alexander Zemlinsky (1911–1927). Alongside works of his own, Zemlinsky performed compositions by figures including Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Ernst Krenek, and Franz Schreker. Moreover, 1924 saw him conduct the world première of Arnold Schönberg’s monodrama Erwartung. And when the Vienna State Opera took a pass on mounting the world première of Krenek’s opera Karl V.—the first twelve-tone opera—out of political opportunism in anticipation Austria’s takeover by Nazi Germany, the première was instead held in Prague on 22 June 1938. Krenek himself refrained from attending the performance—a decision that he retrospectively characterised as having been out of his fear of persecution and defamation. The Vienna State Opera’s first performance of Karl V. would not take place until 1984.

It was amidst this highly charged cultural situation that Hans (Hanuš) Winterberg grew up. Born in Prague in 1901 as the grandson of an Aussig-based rabbi and cantor, he first pursued musical training at the German Academy of Music and Performing Arts in Prague under teachers including Fidelio Finke (composing) and Alexander Zemlinsky (conducting). He then went on to study under Alois Hába at the Prague State Conservatory, where Gideon Klein was among his fellow students. Following the collapse of the monarchy, the Winterberg family declared itself česká [Czech] in the Czechoslovakian census of 1930—a self-definition that was not to remain without consequences amidst the increasingly ethno-nationalist climate of those times. Hans Winterberg married the non-Jewish pianist Maria Maschat, and their marriage produced a daughter, Ruth.

With the National Socialist occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1939, there commenced a step-by-step process of social, economic, and physical destruction. The company owned by Winterberg’s father was “Aryanised”, and 1942 saw his mother deported to the extermination camp Maly Trostenets—where she was murdered. Winterberg’s marriage with Maria Maschat was forcibly dissolved as a consequence of the National Socialist racial laws, and Winterberg himself was impressed as a forced labourer. It was thanks only to the late date (during January 1945) on which he was sent to Theresienstadt that he escaped the mass transport of Jewish musicians from there to Auschwitz in October of 1944—a deportation that meant death for figures including Viktor Ullmann, Hans Krása, Pavel Haas, and Gideon Klein. Hans Winterberg thus became one of the few survivors from that important generation of Czech-Jewish composers whose works and biographies were long to remain on the margins of cultural memory due to the Shoah, exile, and psychological repression.

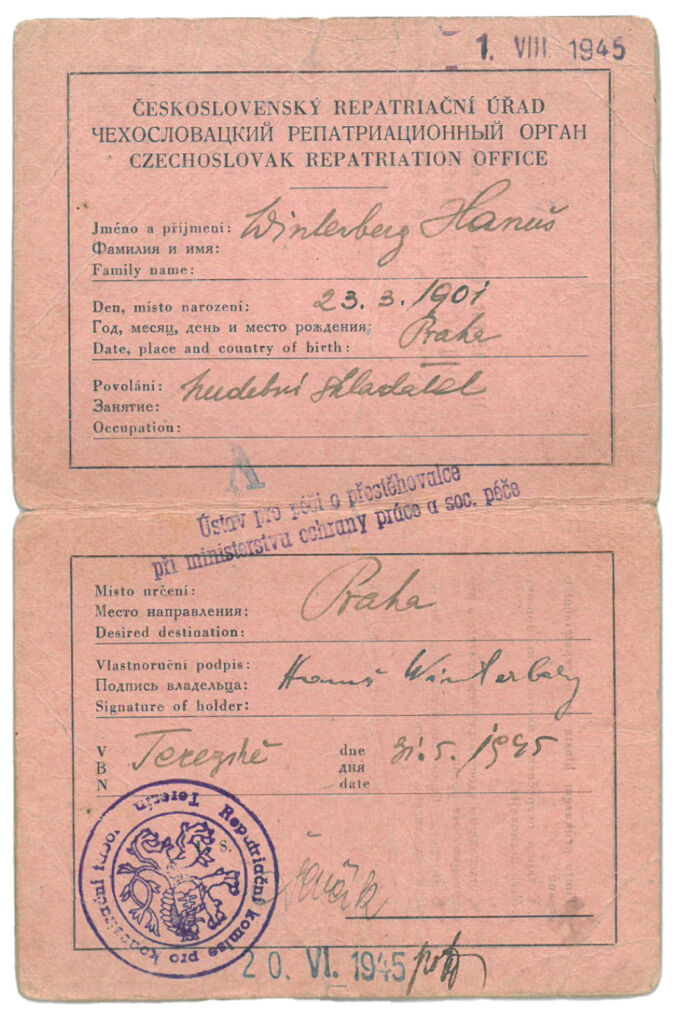

By the end of World War Two, Hans Winterberg had lost numerous family members and close friends. As one who had been interned in the Theresienstadt ghetto, he was stateless and faced with fundamentally uncertain future prospects. In this existentially precarious—though not entirely hopeless—situation, the fact that he and his family had asserted Czech national belonging as early as 1930 proved decidedly advantageous. This earlier self-identification provided a legal basis upon which his repatriation could be officially recognised, making it possible for him to apply for a Czechoslovakian passport. In his passport application, the matter of his forced divorce from Maria Maschat in 1944 was not taken into account. In an attached letter, Winterberg indicated various motivations behind his passport application—referring in particular to a desire to recover musical manuscripts situated abroad (i.e., in the possession of Maria Maschat). By that point in time, the prevailing legal and political conditions had changed fundamentally due to the implementation of the Beneš Decrees, which had entailed the forced expulsion of the German—i.e., non-Czechoslovakian—populace along with revocation of their citizenship. Maria Maschat was among those affected by this and had to emigrate to Germany, and Winterberg followed her into exile shortly thereafter. He was never again to set foot in Czechoslovakia, which then fell under communist rule.

Over the decades following the Second World War, it was only in part that Hans Winterberg—out of desire or out of compulsion—managed to integrate himself into the Sudeten German community in Bavaria. As a Jewish emigree with Czechoslovakian roots, he remained marginalized by society and subject to constant reservations as well as subtle exclusionary mechanisms. His cultural and national identity—especially his Jewish origins and his connectedness with Bohemian musical culture—proved incompatible and hence failed to mesh with postwar Sudeten German society’s conservative self-conception. Although his music was occasionally included in the programming of Bavaria’s state broadcaster Bayerischer Rundfunk, he largely failed to garner any attention outside of the region. This was owed in part to the dominant trends in postwar musicology and music criticism, which devoted themselves primarily to promoting avant-garde tendencies and largely ignored or disparaged compositional stances situated outside of that discourse.

An especially problematic aspect of Winterberg’s overall reception is the treatment of his artistic legacy. In 2002, these materials were sold by his adoptive son to the Sudeten German Institute of Music in Regensburg (funded by the Bavarian district of Oberpfalz) for DM 6,000—under the condition that any and all references to Winterberg’s Jewish origins be suppressed and that everything remain under lock and key until 2030. These requirements represent a significant case of posthumous exclusion and structural antisemitic discrimination that exemplifies the problematic post-1945 treatment of Jewish cultural heritage in German-speaking countries. It was only thanks to the determined efforts of Winterberg’s grandson Peter Kreitmeir that these circumstances were made public and subjected to critical assessment. Since then, it has been possible for the mdw’s Exilarte Center to devote scholarly study to and publish Winterberg’s oeuvre in edited form in cooperation with the publisher Boosey & Hawkes. Moreover, recordings of Winterberg’s works have since been released by eda records, Toccata Classics, and Capriccio.

Veranstaltungstipp: Konzert mit Kammermusikwerken von Hans Winterberg

15. Oktober, 19 Uhr, Kleiner Ehrbar Saal