In its current exhibition, the mdw’s Exilarte Center has created a space of remembrance for an exiled Viennese composer.

Erich Zeisl was born in Vienna in 1905, and it was with flying colours that he passed his entrance examination at the Academy of Music and Performing Arts Vienna (today’s mdw). However, he was not to complete his studies in theory, composition, or piano: Zeisl’s entry in the matriculation register confirms that he ended his pianistic training prematurely due to problems with his hands and attended “Theory of Harmony” with Richard Stöhr only during the 1920/21 academic year. Thereafter, Stöhr taught him privately.

Zeisl’s eventual debut as a composer was a brilliant one: his Piano Trio Suite, full of romantic gestures, is a representative early piece—the “spirited, gifted work of a sixteen-year-old”,1 as the daily paper Arbeiter-Zeitung wrote following its première at the Wiener Konzerthaus in 1928. As a composer of art songs, Zeisl understood how to have the singing voice and the piano interrelate within finely nuanced interpretations of the lyrics, as part of which he augmented his late-romantic idiom by moderately modern stylistic elements. His focus on art songs led him briefly to that “keeper of tradition” Joseph Marx before he went on to absorb impulses from Hugo Kauder, an innovative personality more attuned to modernism.

In 1934, Paul A. Pisk described Zeisl as one of “the strongest personalities among Viennese composers under 30 years of age”.2 Zeisl’s oeuvre at that time encompassed art songs, chamber music, and choral works, the early opera Die Sünde [The Sins], the jazz-tinged ballet Pierrot in der Flasche [Pierrot in der Flask], the Kleine Messe [Little Mass], and the work-in-progress Requiem Concertante. With his sensuously dancing Pierrot in der Flasche, Zeisl made a foray into the world of the grotesque—which he had already traversed in his previous song cycle Mondbilder (after Christian Morgenstern). Currency and a penchant for experimentation are conveyed by two of his later choral works: Afrika singt [Africa sings], which reaches into the popular sphere, picks up where the jazz-inspired Pierrot left off, while the suggestive Spruchkantate [Cantata of Verses] with sayings by Silesius, Salomon, and Goethe explores new effects in choral music. In subsequent works such as his Passacaglia and Kleine Symphonie [Little Symphony], Zeisl exploits the capabilities of a large orchestra and writes in a more traditional vein. The world première of the singspiel Leonce und Lena, for its part, had been planned to take place at the Schönbrunner Schlosstheater in early 1938, but Austria’s annexation by Nazi Germany in March of that year shattered that prospect: Leonce und Lena was struck from the programme, and Zeisl was blacklisted by the Nazis.

10 November 1938 saw Zeisl flee from Vienna to Paris amidst dramatic circumstances. It was a pivotal moment in Zeisl’s life: from this point onward, his musical language would emphasise his Jewish heritage—a turn that he initiated in his composition of stage music to Joseph Roth’s novel Job. The Zeisls then left Europe prior to the outbreak of World War II, with an initial period in New York serving as the springboard for a life in Hollywood. Hans Kafka, who was already working in Hollywood, arranged their move to the West Coast. The initial Hollywood euphoria, however, soon gave way to disillusionment and frustration: after just 18 months, MGM cancelled his contract with him.

It was only through composing his Requiem Ebraico that Zeisl managed to escape his Hollywood misery: “It is so refreshing to find a composer in Hollywood who can still divorce himself from the false glitter of film music and devote his spare time to writing music to a religious text,”3 goes one reaction to the Requiem Ebraico’s April 1945 world première in Los Angeles. Zeisl’s learning of the murder of his father and stepmother, who had been deported from Theresienstadt to the Treblinka extermination camp in 1942, had caused the work—a setting of Psalm 92 originally commissioned by Reform rabbi Jacob Sonderling—to take on a new significance. The composer ultimately dedicated this psalm setting, understood here as a requiem for the Jewish people, to his murdered “father and the other countless victims of the Jewish tragedy in Europe”.4

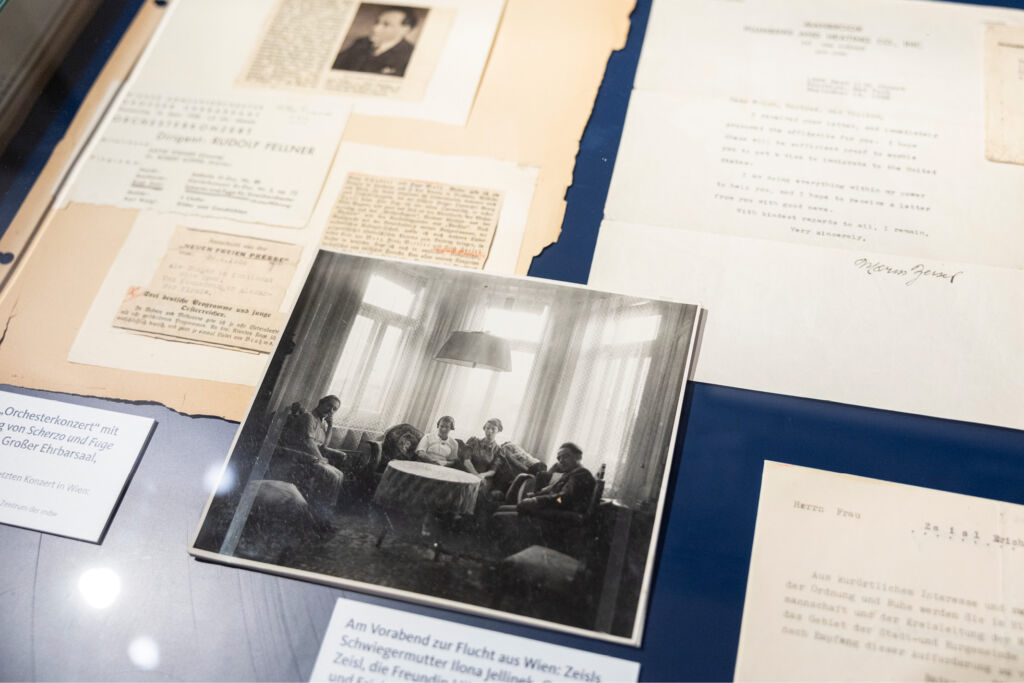

The quintessence of Zeisl’s artistic expression in exile was his synthesis of the musical language he had developed in his homeland with the Jewish idiom. This new language was to shape further compositions such as the Songs for the Daughter of Jephtha, the choral work From the Book of Psalms, and the biblically themed ballets Naboth’s Vineyard and Jacob and Rachel. Erich Zeisl’s sudden and entirely unexpected death came in February 1959 following his delivery of a lecture at Los Angeles City College. He had never returned to his home city of Vienna. A few years before, in May of 1955, the writer Hilde Spiel had authored a text on him for the newspaper Neues Österreich: “Today, the Viennese musician Erich Zeisl celebrates his fiftieth birthday far from home […].”5 Spiel provided a brief look back upon the composer’s Viennese years and went on to speak pointedly of him as “Vienna’s lost son in foreign lands”.6 Until recently, Zeisl’s estate had been archived at the University of California, Los Angeles and at the Zeisl-Schoenberg home in Los Angeles. (Zeisl’s daughter Barbara married Arnold Schönberg’s son Ronald, and the two still reside in the house in Brentwood that Arnold Schönberg had moved into with his family in 1936.) 2024 then saw the Zeisl-Schoenberg family select the mdw’s Exilarte Center as the entire Erich Zeisl estate’s future home. The arrival of these materials in Vienna hence provides a wonderful opportunity to create a space of remembrance for “Vienna’s lost son in foreign lands” at the mdw in the form of an exhibition bearing these words in its title.

Eric Zeisl – Vienna’s Lost Son in Foreign Lands can be seen at the mdw’s Exilarte Center until 20 December.

Literature:

Karin Wagner, Fremd bin ich ausgezogen. Erich Zeisl – Biografie, Czernin 2005. www.czernin-verlag.com/buch/fremd-bin-ich-ausgezogen-

Karin Wagner (ed.), … es grüsst Dich Erichisrael. Briefe von und an Eric Zeisl, Hilde Spiel, Richard Stöhr, Ernst Toch, Hans Kafka, u. a., Czernin 2008. www.czernin-verlag.com/buch/es-grusst-dich-erichisrael

- Arbeiter-Zeitung, 7 May 1928.

- Paul A. Pisk, “Erich Zeisel” [sic], in: Radio Wien, 26 Jan. 1934 p. 2–3.

- The Tidings, 13 April 1945, Estate of Erich-Zeisl, Exilarte Center, Vienna.

- Forword to Erich Zeisl’s Requiem Ebraico, Transcontinental Music Corporation 1946, TCL no. 266.

- Hilde Spiel, “Erich Zeisl, fünfzig Jahre”, in: Neues Österreich, 22 May 1955, p. 8.

- Ibid.