A queen has commanded her servants to gather sticks, which they’ve already begun placing before her in a gigantic pile. She exhorts them to bring more and ever more, and they industriously do as they’re told. Finally, the queen takes the pile in her hands—with everyone staring at her, their breath held—and hurls the laboriously collected sticks onto the pavement, scattering them in all directions. It is an act of ultimate caprice.

This queen and her servants are pre-schoolers whom Claire Simon followed in her 1993 documentary Récréations [Playtime]—and it’s as a viewer here at the Austrian Film Museum that one can learn this film’s first lesson from Claire Simon herself: “Characters have no age,” she states in the Q&A session. What she means is that if one just observes people closely enough regardless of how old they may be, if one takes them seriously, one can recognise them for what they are: active protagonists of their own stories.

The children in Récréations spend their daily recess in a dreary grey back courtyard in Paris—and even so, their imaginings there give rise to all manner of worlds. Within a few brief seconds, one can go from policeman to jailbird. It’s all about courage, power, boundaries, and affection. In her films, Claire Simon succeeds in shedding light on the inherently human. And as palpable as her great love for her characters may be, she doesn’t view them through rose-coloured glasses. The audience senses a certain direct honesty towards the people shown us by her camera.

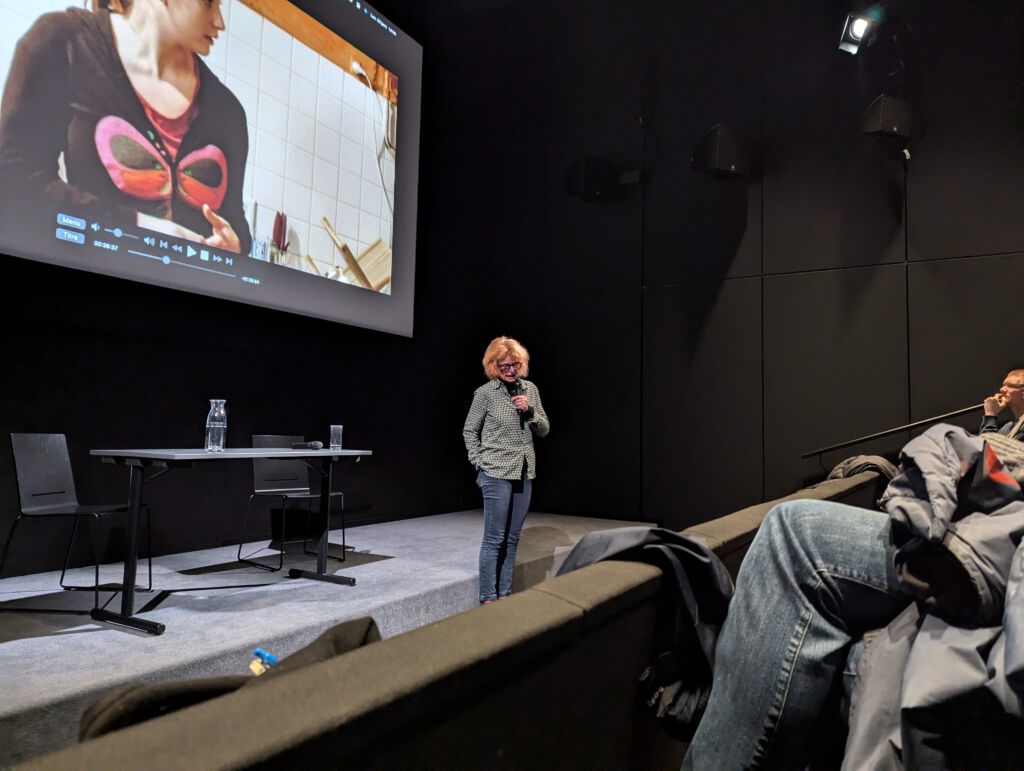

In conjunction with the Claire Simon retrospective Jedes Leben ist ein Roman [Each Life Is a Novel] at the Film Museum from 17 January to 24 February 2025, the filmmaker herself came to Film Academy Vienna, the mdw’s Department of Film and Television, for a one-day seminar on 20 January. Students had the opportunity to discuss Simon’s films with her at the Arthouse Cinema, the University’s own movie theatre. There, she also showed several excerpts from works both older and more recent—mainly documentaries, but also feature films.

For most of her films, she not only served as the director but also wrote the screenplay and assumed responsibility for cinematography—meaning that she operated the camera while directing. The complex approach of simultaneously involving oneself in multiple areas of work “simplifies my process”, she says, since it reduces the translational effort involved in communication.

Quite generally, this master class saw Simon speak of her fondness for producing documentary works alone or in a small team as well as how she goes about doing so. Her works, she said, are inseparable from her person and often have an autobiographical angle—being set in places and zeroing in on situations that have figured into her own life. Récréations, for example, was filmed at a preschool attended by her daughter. And in Notre corps [Our Body] (2023), Simon bears witness to numerous conversations between physicians and patients in the gynaecology ward of a Parisian hospital. She herself becomes an unhappy protagonist later on this film—for it was during the filming process that she ended up receiving a breast cancer diagnosis of her own. “It was practical. I’d always wanted to film a patient receiving a cancer diagnosis. The doctors, of course, told me that they couldn’t allow a conversation like that to be filmed. But when I had such an appointment myself, I could film it, at least. So it was of value. I got lucky.” This quotation says a lot about how Clair Simon comes across: she’s precise, interested equally in processes and outcomes, direct, and ironic while refraining from cynicism.

Claire Simon laughed a lot during this master class, which she was loathe to actually describe as such (“I’m not a master.”). She spoke in mostly positive but occasionally negative terms of her collaborators over the years—and in characterising particular individuals, she’d often start by describing their humour: “She was very funny. A very funny person. She was also a great editor.” Diving into Simon’s oeuvre with her was fun—with even just a five-minute excerpt of a film capable of leaving participants moved or enthused. All who were present felt the need to say something. Claire Simon answered every question, occasionally contradicting students when she felt misunderstood, and the questions that got asked often moved her to wax philosophical. Filmmaking, one notices while listening to her, is a way to collect and formulate stories in a world that’s full of them. Any person can pick up a camera and an audio recorder and document the world through their own eyes, allowing people to speak that wouldn’t otherwise be heard. From Claire Simon’s oeuvre and from her person, the participating students took inspiration for their own filmmaking.

Great thanks are due here to the documentary film directing lecturer Constantin Wulff for organising this retrospective at the Film Museum and to directing professor Barbara Albert for her support in realising this master class. The experience was a deeply enriching one for all participants, and it can be hoped that the associated retrospective contributes to making Claire Simon’s sublimely sensitive films accessible to a broader audience in Austria.