How to cite

How to cite

Outline

Outline

For the analysis of the social organization of arts, many sociologists resort to social theories in order to explain the formation and transformation of social order, collective action and processes of interpretation and valuation of arts. They generate a perspective on the arts as a social activity that is connected with other social domains such as religion, business, education, labor, technology, legislation and ethics, to name just a few. This approach links different organizational arrangements to society on a superordinate scale (e.g., Clegg and Pina e Cunha 2019). Although the connection to social theories definitely has its merits, theoretical considerations are not easily transferable to the empirical level.

The approaches of the previous three chapters – the Production of Culture Perspective, the Sociological Neo-Institutionalism, and the Cultural Institutions Studies are interconnected to various theoretical sources in sociology, but they all have the advantage of being relevant in empirical studies, for example, of arts management or arts policy.

-

The Production of Culture Perspective is inductively developed. Cultural Institutions Studies uses inductive findings and some deductive derivations as its basis. In contrast, Sociological Neo-Institutionalism is largely grounded on theories such as structuration theory (Giddens), ethnomethodology (Garfinkel) and social dramaturgy (Goffman). It explicitly criticizes utilitarian theory as underpinning the dominant understanding of organizational behavior as rational (Simon and March). Nevertheless, Neo-Institutionalism started from empirical findings of the Columbia School of Organizational Sociology, it also has inductive roots. None of the three theories seeks to formulate a grand theory but they do claim middle-range results (see Brodie et al., 2011).

-

The Production of Culture Perspective, Cultural Institutions Studies, and Sociological Neo-Institutionalism use terms like industry, institution, or sector to describe large-scale societal phenomena. These three theories reject methodological individualism and therefore insist that organizing arts cannot be explained as the aggregate result of individual actions. They would argue that, for example, the popular music industry is nothing but a large network of music worlds, beyond individuals who produce, perform and distribute a certain kind of music.

-

All middle-range theories of arts organization build alliances with many other disciplinary approaches, especially with organizational and occupational sociology, arts management studies, cultural economics, cultural policy studies and the humanities. This transdisciplinary spirit has been their trademark, particularly in arts management research (Paquette and Redaelli 2015, 7–17).

-

All these three middle-range theories refer to Giddens’s structuration theory, bridging the dichotomy of structure and agency when studying arts organizations and organizational practices. Even the Production of Culture Perspective resonates with structuration theory when analyzing strategic action as motivated by reward patterns (Crane 1976) or when exploring the role of gatekeepers (Peterson 1994), as Santoro (2008a, 24) notes.

-

All three approaches have at least tacitly arrived at a single-level social ontology by connecting different aggregation levels of the social (see DiMaggio and Hirsch 1976; Zembylas 2004a, 40, 99f.; Steele et al., 2020).

The three perspectives (we do not use the term schools because the groups are intellectually open and have not created an orthodoxy of their respective views) use different basic concepts, and address different research questions. However, their approaches display some resemblances and are to a large degree compatible with and complementary to each other. So, most scholars of these perspectives are skeptical about a single logic or one overriding infrastructure that shapes the cultural production and the relations between creators and consumers. For example, arts managers who are generally considered to have a crucial control over resources and play a key role in arts organizations, are also intermediaries between different institutional spheres (e.g., arts producers, arts market organizations or arts communicating media) and various social groups (e.g., creators, sponsors, critics and consumers) (see Peterson 1986; DeVereaux 2019b). However, the variety of situations, the complexity of social relations and the diversity of mediation types imply a lack of an overarching rationality and of a singular institutional logic that could essentially characterize managerial practices. All three perspectives reject social determinism and underline the relevance of situational particularities and contingencies. Nonetheless they acknowledge that global and local power relations, institutional constraints and established practices lead to overarching cognitive and structural patterns. These patterns are not necessarily developed hierarchically, that is, top-down, but also bottom-up. Social structures are shaped by shared experiential learning processes and common material practice arrangements too.

There are differences as well, but these are not too substantial. For instance, Richard Peterson uses the term industry while neo-institutionalists use the term sector or field. Scott and Meyer mark the difference as follows:

A societal sector is defined as (1) a collection of organizations operating in the same domain, as identified by the similarity of their services, products or functions, (2) together with those organizations that critically influence the performance of the focal organizations: for example, major suppliers and customers, owners and regulators, funding sources and competitors.… However, the concept of sector is broader than that of industry since it encompasses the different types of organizations to which these similar providers relate. (Scott and Meyer 1991, 117)

Without denying the analytical point of the authors, we think that Peterson also has a broad analytical scope when he refers to the six facets and notes that some of them, for example, law and technology, exceed the reach of a given industry. Many scholars of Cultural Institutions Studies take an intermediate position. They frequently use the term industry in its widest sense, referring to “a specifiable overall ‘clustering of institutions’ across time and space” (Giddens 1984, 164; see Zembylas 2004a, 13) and to a large number of people who cooperate with and compete in the production and distribution of certain groups of artistic goods and services.

Another difference is that scholars associated with Cultural Institutions Studies explicitly discuss ethical and political issues, for example, questions of wellbeing, inclusive policies, issues of cultural diversity or of discrimination, nepotism, transparency, fairness and distributive justice (see Mathieu and Visanich, 2022; Zembylas 2004, 109f., 310ff.; Zembylas and Alton 2011). Scholars associated with the Production of Culture Perspective or Neo-Institutionalism are, although sensitive to these issues, less explicit and even restrained. This might be related to the different roles of the social sciences in North America and in continental Europe, to different academic values and to different ideas of the relation between arts, state and civil society.

In the further course of this chapter, we will focus on two particular topics. First, all three middle-range theories can be described as contextualist, and they have developed methodologies for contextual analysis. We will be discussing their understanding of contextual relations and contextual analysis. Second, all three theories focus on mediation among the main groups of organizing arts, creators, distributors and consumers. Mediations actively shape (and are shaped by) the meanings of artworks, and arts’ social role and impetus, as sketched out by the Cultural Diamond (Alexander 2003 [2001]; Griswold 2004 [1994]).

1 Context as a major concept for comparing the three middle‑range theories

General remarks on the emergence of contextual thought

The idea of contextual relations emerged in the 19th century and is associated with an understanding of social and cultural transition as a dynamically evolving process, which – as it was then generally believed – follows intrinsic and determining conditions or driving forces. For Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, it was the “spirit of the times,” the progression of zeitgeist; for Karl Marx, class struggle; for Herbert Spencer, the principles of social evolution; and for Wilhelm Dilthey, tradition and the respective historical and social environment. Many early sociologists – for instance, Émile Durkheim, Max Weber and Georg Simmel – therefore viewed social phenomena like professions, rules, bartering relationships, various forms of artistic expression and religious forms of life as conditional, dependent and evolving.

The very idea of context implies a given situation that is shaped by its own surroundings. Figuratively speaking, it is a container or frame in which social phenomena are embedded. In other words, the different concepts of context, embedding, situatedness and relationality go hand in hand with a specific social ontology, namely, the assumption that social reality does not consist of isolated monads, but of interrelated and interdependent entities (see Granovetter 1985).1 The logician Gottlieb Frege (1953 [1884], xxii) formulated the so-called context principle: “never ask for the meaning of a word in isolation, but only in the context of a proposition.” The term context (in Frege’s German Sinnzusammenhang) refers on the one hand to the inherent logical and semantic relations between the words in a sentence and on the other to the circumstances under which a statement is made and understood. Wittgenstein (1922, §3.3, §3.314), incorporated Frege’s ideas into his own theory of meaning. We point this out in order to emphasize that the concept of context is intrinsically associated not only with a social ontology, but with a basic theory of meaning as well.

Context was also relevant in pragmatism and explicitly in John Dewey’s work. “When context is taken into account,” Dewey (1985 [1931], 8) writes, “it is seen that every generalization occurs under limiting conditions set by the contextual situation.” Later he defines the term as follows, “Context includes at least those matters which for brevity I shall call background and selective interest.… A background is implicit in some form and to some degree in all thinking. Background is both temporal and spatial.” (1985, 11) By selective interest he refers to “the subjective, [which] is after all equivalent to individuality or uniqueness.” Dewey (1985, 20) also names

three expanding spheres of context. The narrowest and most superficial is that of the immediate scene…. The next deeper and wider one is that of the culture of the people in question. The widest and deepest is found in recourse to the need of general understanding of the workings of human nature.

Since then, the idea of context has become a basic concept for most social theorists and empirical sociologists. The statement made by Anselm Strauss and Juliet Corbin (1990, 131) is exemplary of this notion:

The context is the specific set of properties of the phenomenon – the conditions – in which actions are embedded…. The context is really an arrangement … of the properties of the general phenomenon ordered in various combinations, along their dimensional ranges, to form patterns.

Or, in the words of Theodore Schatzki (2002, 21):

Context-forming configurations of life characterize all social phenomena, from chance meetings on the street and local council meetings to the world credit market and international crime syndicates. Indeed, a phenomenon is social to the extent that it embraces or pertains to so-configured lives.

Let us close this discussion by indicating some problems of contextual analysis. The basic assumption is that the objects of social research exist within contextual relations, and therefore sociological analysis aims to examine these multiple interrelations in a given situation. Accordingly, it is important to provide a comprehensive specification of the term relation, and we therefore need to ask what kind of relations and conditions can exist between a research object and its context (e.g., social arrangements which include people and organizations, natural objects and artifacts, symbolic forms and symbolic entities, institutions, etc.)? In principle, different relations may occur:

-

Causal relations, where a condition or a well-defined variable is considered as the cause of the emergence, evolution or disappearance of a social object (x makes y happen). Typically, claims of causality are associated with claims of social stability, and reproduction of social structures.

-

Conditional relations, which can be either constitutive (a necessary relation) or regulative (i.e., enabling or restrictive) can be one-way or reciprocal. The idea of conditional relations suggests the formation of social patterns.

-

Modal relations, which play a role in the emergence and alteration of a social entity. The idea of modality and interdependence suggests an increase of social dynamics and unpredictable events. Therefore, such relations differ from causal or conditional relations.

-

Transitive relations, which occur when an attribute of an institutional sphere is transferred to an object that penetrates that sphere (each object that penetrates the market contains a monetary value). Transitive relations refer to how institutions channel activities.

These relations are derived from formal logic. Since social relations occur in a spatial-temporal continuum, there are two additional types of relations:

-

Spatial relations, which refer to spatial or geographic positions (e.g., up/down, in/out, proximity/distance or north/south).

-

Temporal relations, which indicate a position within a particular concept of time and temporality, which extends the physicality of time. They also include the history of previous events and relations.

Finally, there is another category relevant to social analysis, which takes into consideration how people actively relate themselves to a situation in general.

-

Intentionality (or directionality), which refer to interpretations, sense-giving and addressing situations and the active attitude people have toward their social environments. However, the concept of the “affordance” of objects (see Greeno 1994) also ascribes to artifacts a kind of intentionality, since they practically invite people to use them in a certain way.

Yet no relation can be taken for granted, but needs evidence. Another problem of contextual analysis is the extension and delimitation of what researchers mark as context. Presumably, there are a number of reasonable answers to this problem since theories of the social organization of arts are grounded on different social ontologies and theories of meaning. Here we want to underline that the way sociologists think of their research objects shapes their understanding of context and vice versa. Therefore, both aspects, research object and context, maintain a reciprocal relationship, that is, they constitute each other.

Concrete contextual analysis, we believe, must be pragmatic by focusing on case-specific and empirically founded research designs. “Being problem-dependent, the relevant features of the context are those that will contribute to generating a convincing solution of the puzzle” (Boudon 2014, 19). The three middle-range theories discussed here do exactly this: they give primacy to those contextual aspects that are empirically tangible.

The role of context in the three middle-range theories

The Production of Culture Perspective looks at the industrial and organizational conditions of cultural production and emphasizes the interrelatedness of production with other domains that are not genuinely cultural or artistic. Here context is understood as specific and empirically explorable relations between an artwork’s production and its social, cultural and industrial environment (see Crane 1992, ix, 112f.). Peterson’s distinct facets – legal framework, technology, industry structure, organizational structure, markets and occupational roles – explain changes in cultural production (Peterson and Anand 2004; see Crane 1992, 120). He considers the context of cultural production – in his words, facets – as ontologically real, that is, as trans-subjective structural constraints and windows of opportunity. The actors in the production process perceive facets at their discretion. Objective structuring conditions are affected by subjective assessments and are by no means factual occurrences.

The understanding of context varies in Cultural Institutions Studies. Zembylas (2004a, 91f.; 2019b; see Hasitschka 2018, 139ff.) takes a constructivist stance and argues that context – which he understands as a complex web of temporal, spatial, material/medial and intertextual aspects – is constructed by scientists in line with their particular research direction to facilitate analysis and interpretation. Other scholars (e.g., Tschmuck 2012) identify surrounding institutional spheres, similar to Peterson’s facets, and focus on their synergies. They also emphasize the importance of a particular situation and therefore make use of case studies to explore similarities and differences (see Schad 2019; Tschmuck 2001b). Another example can be given from the work of Kirchberg (2003; 2005), who contextualizes arts organizations like museums by assigning specific temporal and spatial functions in urban settings that socially legitimize them. Such functions compel museums to deliver a postindustrial urban purposiveness with respect to the physical, mental and political space of a city.

Sociological Neo-Institutionalism has also developed a particular understanding of contextualization. Since organizations “do not exist and compete as individual autonomous units, but as members of larger systems” (Scott 1992, 160), they cannot be understood without taking into account their relations and interdependencies with other organizations and with their extended environment (see Scott and Meyer 1991, 137). Their environments wield power by generating broadly accepted norms (DiMaggio and Powell 1991b), institutional logics (Friedland and Alford 1991), the density and scale of networks (Powell 1990) and sector-wide cultural forces such as social cognition that is, trust and credibility (Zucker 1977) or moral legitimacy (Suchman 1995). Because the terms environment, network and culture are semantically open, Neo-Institutionalism has elaborated particular analytical ways to use them. For instance, Richard Scott and John Meyer look at the organizational environment and distinguish between the institutional, spatial, political and control sectors. Their analytical view allows for the use of case-specific contextual analyses “in order to (1) consider the determinants of these characteristics at the sector level; and (2) examine the relations between these characteristics and the properties of organizations functioning within the sectors” (Scott and Meyer 1991, 122).

A prominent example for the application of this type of contextualization is DiMaggio’s study of the institutionalization of North American art museums in the first half of the 20th century. Before the First World War, most art museums were privately owned and reflected the particular interests of their wealthy patrons (DiMaggio 1991a, 170; see Alexander 1996a, 20). Changes to museums’ financial structures and their relations to the public, and the emergence of publicly funding facilitated the professionalization of its staff, the establishment of umbrella associations (such as the American Association of Museums), the development of standardization, quality control and museum ethics, together with increased means of support, better flows of information and the emergence of informal professional networks. One important result of this transformation was an increase in managerial agency, which led to a collective definition of the organizational field (DiMaggio 1991a, 275–277; see Mometti and Van Bommel 2021, for a recent example). This example shows that processes of scales and differences in organizational cultures are based on processes in the surrounding contexts, that is, the sector. In line with Giddens (1979; 1984), DiMaggio (1991a, 287f.) speaks of a structuration process that incorporates the duality of social structure and agency. On the one side, structural sector-caused developments drive and foster change of an organization; on the other, organizational actors also shape their environment and sector, for example, through their collective action.

All three middle-range theories – Production of Culture, Neo-Institutionalism and Cultural Institutions Studies – thus fall back on context-related concepts like environment and sector when explaining the emergence of and changes in cultural production structures and processes, and of arts organizations’ power or weakness. The three theories provide slightly different interpretations of contextual relations among arts and their environments. Contextualization involves selective interpretation, and there might be different forms and ways of contextualization according to different theoretical understandings, methods and research directions.

2 The Cultural Diamond template of comparing the middle‑range theories

The emergence of the Cultural Diamond

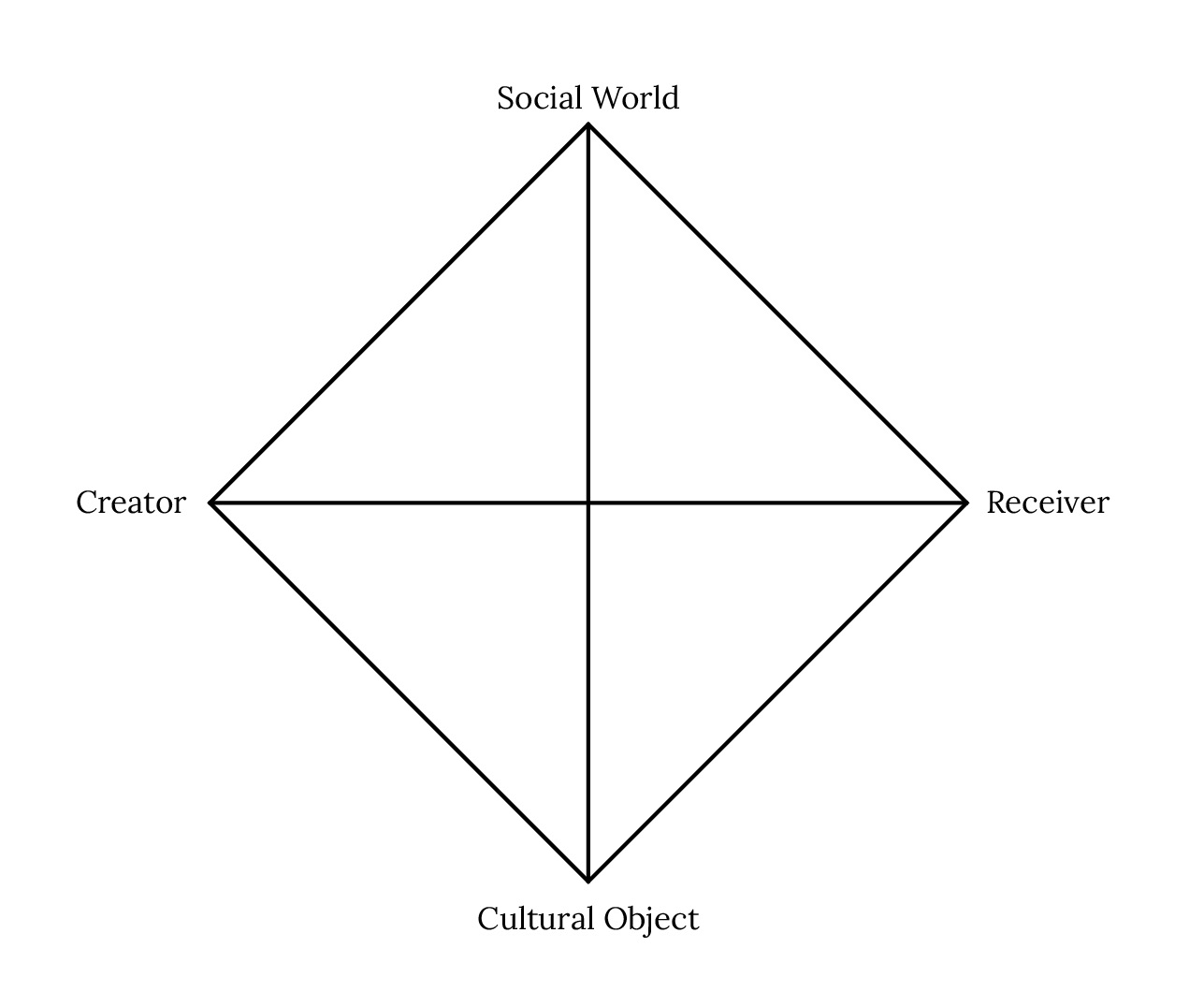

Intrinsically connected to the discussion about the meaning and significance of context is the relational sociology of four elements of arts organization (see figure 5), as outlined by Wendy Griswold (2004 [1994], xvi, 16ff.; first published in Griswold 1986, 8). Griswold (2004 [1994], 13) draws the analogy to an ecosystem to illustrate the interconnectedness of four elements: cultural creators (people and organizations involved in arts creation and production), cultural receivers, cultural objects (in general, symbolic forms, and specifically, art objects), and the social world (the social, political and economic conditions of art creation and reception. By doing so she bridges the binary opposition between culture and society and proposes a new nondeterministic model, which can be applied in various empirical cases.

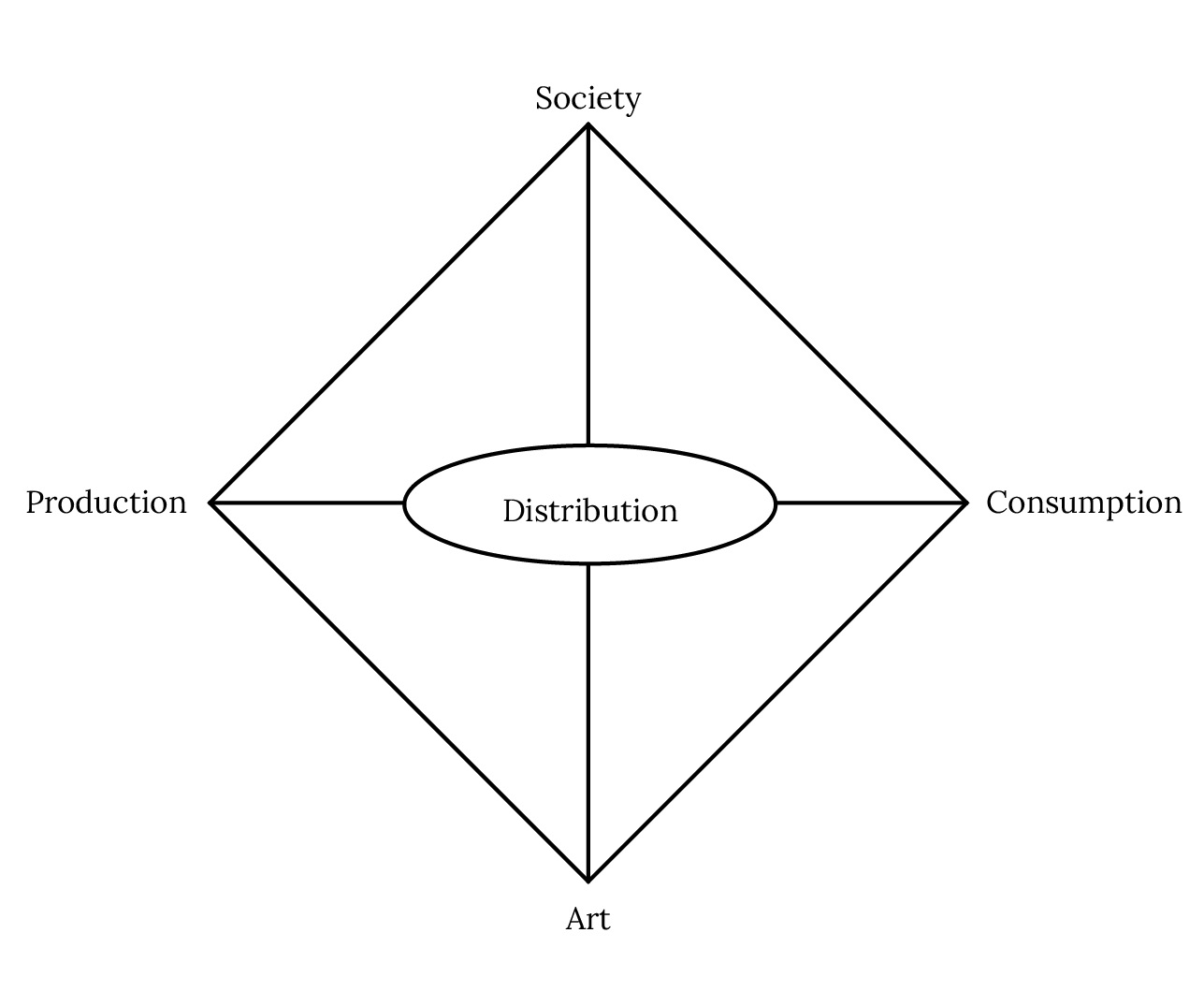

A decade later, Victoria Alexander (2021 [2003], 51) added a fifth element, the distribution of arts, which mediates between the other four elements, that is, creators, receivers, cultural objects and social world (see figure 6). Distributors are individuals (art dealers, art directors, publishers, curators, art critics, etc.), organizations (museums, theaters, concert halls, festivals, art fairs, commercial galleries, digital enterprises, radios, TV stations, art journals, etc.) and networks (formal networks like professional associations, and informal networks based on personal relations and common interests) (2021, 75–88).

Figure 5 The Cultural Diamond (see Griswold 2004 [1994], 17)

Figure 6 The Cultural Diamond, according to Alexander (2021 [2003], 51).

Where Griswold speaks more generally of connections among various cultural elements (not only arts), Alexander focuses on arts and labels the relations among the elements as communication (2021, 50). She applies her model of the Cultural Diamond directly to the analysis of the social organization of arts, emphasizing that “the Cultural Diamond suggests that links between art and society can never be direct, as they are mediated” by distribution (2021, 51). This understanding of mediation makes clear “that cultural products are received by a variety of different audiences, not by a general ‘society’, and that people [that is, specific target groups] vary in what types of cultural products they consume and in what meanings they take from them” (2021). Creators may either work closely with distributors or they may want to distance themselves from these processes, but they will never be unaffected by the ways and means of distribution. No single group, neither creators, distributors, nor consumers, defines a single meaning and value assignment to an art object; instead, meanings and values are multiple outcomes of essentially unpredictable dynamics2 (2021, 76ff.). In summary, the Cultural Diamond is a useful device for contextual analysis and for comparing the three middle-range theories along the lines of the five elements and their relations.

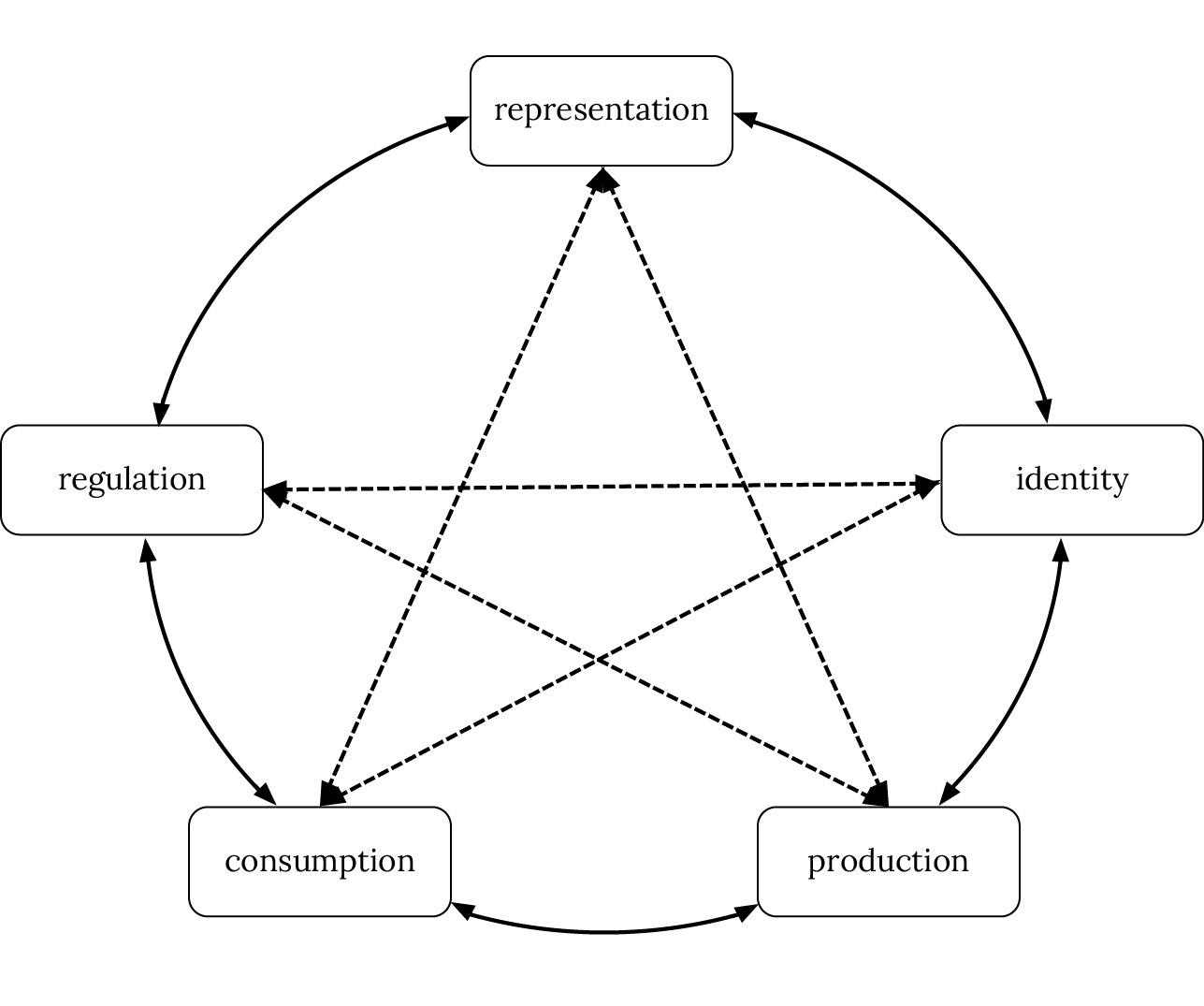

A similar approach has been outlined by Paul du Gay (2013), he calls it the Circuit of Culture. He and his colleagues discuss cultural meaning and value making processes, stating:

The five major cultural processes … are: representation, identity, production, consumption and regulation…. Taken together, they complete a … circuit of culture – through which any analysis of a cultural text or artifact must pass if it is to be adequately studied…. One should at least explore how it is represented, what social identities are associated with it, how it is produced and consumed, and what mechanisms regulate its distribution and use. (2013, xxx)

The circuit illustrates a methodological diagram: “It does not much matter where on the circuit you start, as you have to go the whole way round before your study is complete.” (2013, xxx).

We consider the Circuit of Culture model to complement the Cultural Diamond. Du Gay’s issues of representation, identity and regulation in addition to production and consumption are also embedded in the broader concepts of Griswold’s and Alexander’s elements of social world and distribution. Although the circuit model has its benefits, especially by allowing us to visualize the continuous interconnectedness of all the elements and the poststructural emphasis on representation and identity as key aspects of arts production and consumption, for the purpose of clarity, we will make use of the Cultural Diamond model.

Figure 7 The Circuit of Culture (see du Gay 2013, xxxi).

Cultural and art objects as elements of the three middle‑range theories

Wendy Griswold (2004 [1994]) speaks of cultural objects, and Victoria Alexander (2021 [2003]) of art, while Richard Peterson (1976, 11) speaks of symbols produced in the domains of art, science and religion. Later he emphasizes cultural symbols, which occur in “art worlds, science laboratories, religious institutions, the legal system, popular culture, and similar sociocultural fields, or realms” (Peterson 1994, 163). As an empirically inclined sociologist, he understands culture as “the code by which social structures reproduce themselves from day to day and generation to generation” (Peterson 1976, 16), which approaches the hermeneutical term of cultural objects as used by Griswold. In a pragmatist fashion, the Production of Culture Perspective studies topics like “the fabrication of expressive-symbol elements of culture such as books, paintings, scientific research reports, religious celebrations, legal judgments, etc.” (Peterson 1994, 165) but with the specific sociological purpose of uncovering the major conditions of organized cultural production.

Similarly, the analysis of cultural meanings is also one of the main agendas of Neo-Institutionalism. Scott (2001) has presented this in his three-pillar model that displays the regulatory, cognitive and normative aspects of institutional stability of organizations and society as a whole. The constitution of meaning is particularly pivotal for arts organizations since it reduces uncertainty about their goals and purposes. Neo-Institutionalism describes how meaning-making is an important task for organizations, not explicitly and consciously, but mostly by using “taken-for-granted scripts” (DiMaggio and Powell 1991a, 15).

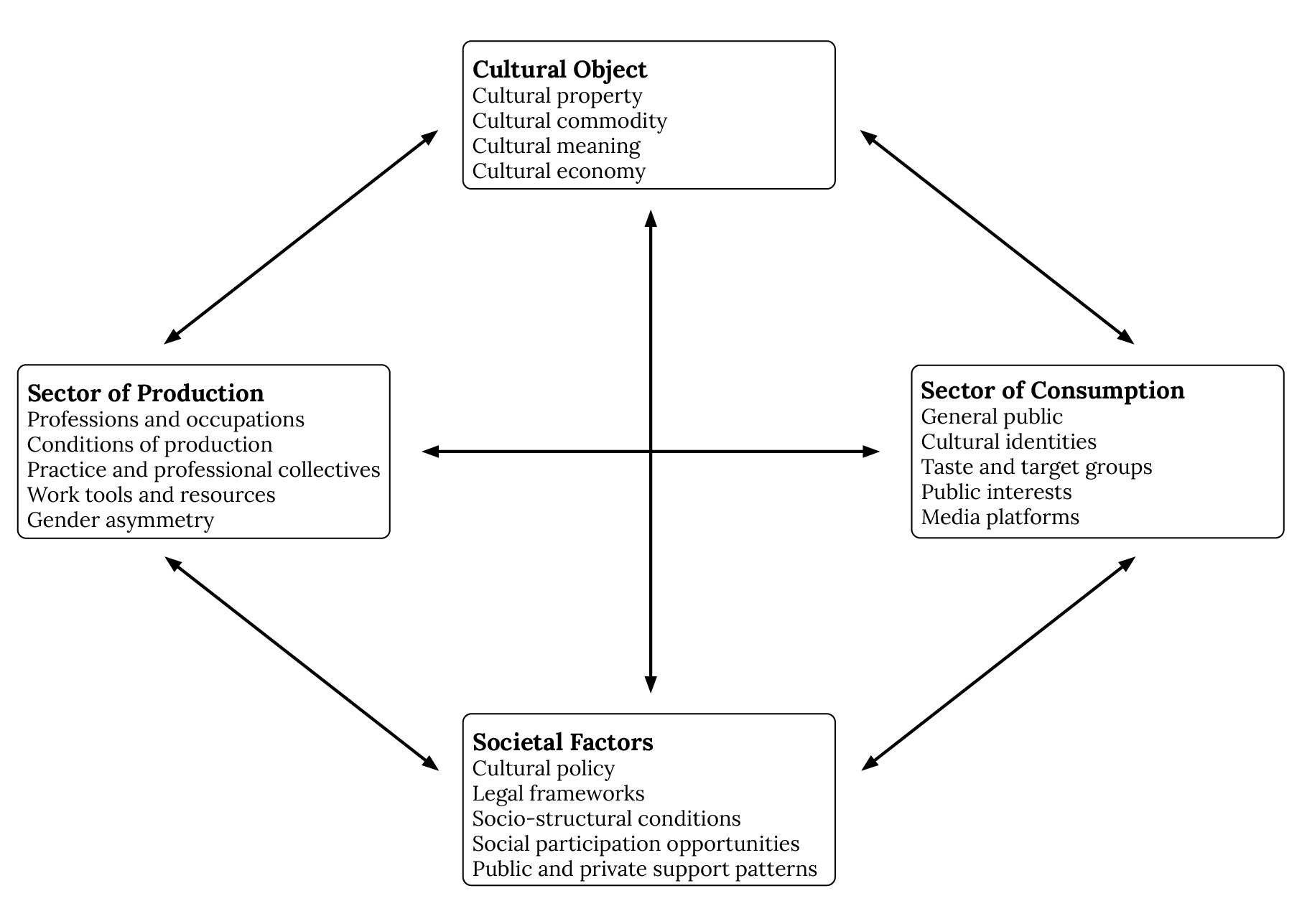

Figure 8 Embedding the Research Objects of Cultural Institutions Studies (adapted from Zembylas and Tschmuck 2006, 9).

Cultural Institutions Studies provides a research model very similar to the Cultural Diamond. In their introduction to the fundamentals of Cultural Institutions Studies, Zembylas and Tschmuck (2006, 8f.) highlight that every analysis of artistic practices and processes implicates the study of the social, political and economic contexts. Their research focus lies on the study of the creation, distribution and mediation of cultural goods under premises of artistic attributions and societal influences. The production and consumption of aesthetic symbols (as carriers of meanings) goes hand in hand with an economic valorization of these symbolic goods in late capitalist and highly industrialized market societies (cf. Boltanski and Esquerre 2020). The posited vicinity of cultural objects to a cultural economy places this theory close to the Production of Culture Perspective. The attribution of meanings to cultural objects, however, places this theory near the organizational task of meaning-making as outlined by Neo-Institutionalism.

Social world as a major element of the three middle-range theories

Griswold’s social worlds and Alexander’s use of society are aligned with Peterson’s (1976, 10) call for sociological research to focus on “processes by which elements of culture are fabricated in those milieux where symbol-system production is most self-consciously the center of activity … turning away from grand questions about the relationship between science and society.” Limiting the concept of society to issues of empirically observable social milieux allows a pragmatist social scientist to set up a plausible research design to develop their hypotheses on middle-range societal structures and processes. Peterson repeats time and again that his approach rejects a general societal perspective, “The danger in looking from the societal level is that the workings of the production process may be seen to follow automatically from the society-level constraints” (Peterson 1994, 181). This is a criticism especially of the Frankfurt School’s analysis of the “culture industry as an expression and reinforcer of the sociopolitical system of the larger society” (1994). The epitome of this pragmatist view on the middle-range concept of society is the six-facet model of the production nexus (Peterson and Anand 2004), limiting the external environment to six elements: technology, law and regulation, industry structure, organizational structure, occupational careers and the market.

Neo-Institutionalism looks at ecosystems of institutionalized organizational sectors to distinguish itself from the old sociological institutionalism that had mainly focused on the structures and processes within organizations. The emphasis on the external organizational environment can be seen especially in the works of Scott and Meyer (1991). They understand such institutionalized sectors as surroundings in which organizations mutually exchange cultural characteristics such as expectations, cognitions and worldviews and reinforce their similarity. The inclination toward isomorphism (DiMaggio and Powell 1991b) and the striving for legitimacy (Deephouse et al., 2017) are the most prominent effects that different societal sectors effects have on organizations.

Similar to the Production of Culture Perspective, Cultural Institutions Studies understands society as a complex of intersecting and mutually influencing practices, often prestructured by institutions. Instead of the six facets, Zembylas and Tschmuck (2006) focus on issues of cultural policy, law, social (i.e., bureaucratic) regulations, participation opportunities and private or public funding as aspects of society. Zembylas illustrates this by the changes of functions and values that cultural goods experience when they enter the sphere of the market. “Since the market itself is a field with its own valuations, it impregnates every cultural good with its own logic by giving it an economic function and value” (Zembylas 2004, 110). However, this does not mean that all the other values that cultural objects represent and generate are pushed into the background. On the contrary, different meanings and values form complex webs according to their particular social embedding (see Zembylas 2019a; 2019b).

Cultural production as a major element of the three middle‑range theories

The understanding of producers (Griswold) and creators (Alexander) in the Cultural Diamond is closest to the concept of creation and cultural production in Peterson (1976, 2004), although he differentiates between creation as the emergence of an artistic idea and the construction of this idea as its realization intended for an audience. In his early works, he also subsumes activities of distribution and even consumption under the term of production. “As used here, the term ‘production’ is meant in its generic sense to refer to the processes of creation, manufacture, marketing, distribution, exhibiting, inculcation, evaluation, and consumption” (Peterson 1976, 10). In his later works he drops consumption from this list and replaces it with the production-related facet of the market: “Markets are constructed by producers to render the welter of consumer tastes comprehensible…. Once consumer tastes are reified as a market, those in the field tailor their actions to create cultural goods like those that are currently most popular” (Peterson 2004, 317).

Neo-Institutionalism is only peripherally concerned with production. Here the production of cultural goods and services is limited to the activities of “institutional entrepreneurs” (Battilana et al., 2009). Therefore, not the output of the production process is of interest, but the social mechanisms that lead to an output, especially the irrational and cultural scripts that cause production decisions (see DiMaggio and Powell 1991a, 15).

Cultural Institutions Studies again is closest to the Production of Culture Perspective when studying cultural production processes under limitations such as scarce work and human resources, the lack of support for innovations and the suppression of creativity, inequalities in the workplace, or the (in)efficacy of producing arts performances at, for example, a theater. Almost identical to Peterson’s list of production processes, Cultural Institutions Studies deals with the “conception, production, distribution, mediation, reception or consumption, conservation and preservation of specific cultural goods and services” (Zembylas and Tschmuck 2006, 7). One important difference between this theory and the others is the introduction of practice collectives and professional collectives as a necessary factor of cultural production. Art is always created by various practice collectives (similar to Becker’s art worlds, see chapter 2), and these communities can be conceived as thought collectives, that is, a community of people who create a common social identity through the same attitudes, language games and ways of thinking and coping with problems (see Fleck 1979 [1935]). Actions in a practice collective are valued by their members as meaningful and legitimate when they are based on mutually recognized symbolic forms, cultural techniques and material foundations. The existence of a practice collective in an arts organization is necessary for the successful production of arts and culture. The professional collective is an institutionalized form of the practice collective, where formal organizational structures are introduced, tasks are formally distributed, hierarchies are introduced and the forwarding of resources, information and remuneration are regulated. Practice collectives and professional collectives are important empirical research objects of the Cultural Institutions Studies (see Zembylas 2004a, 251–257). Another difference is seen in several microsociological studies on artistic creative processes by Zembylas, together with other colleagues, where they analyze various topics from the creators’ perspective (in literature, Zembylas and Dürr 2009; Zembylas 2014b; in music composing, Zembylas and Niederauer 2018).

Cultural consumption as a major element of the three middle‑range theories

The groups of receivers (Griswold) and consumers (Alexander) are certainly connected to the process of consumption, although Peterson (1976, 10) subsumes consumption under the umbrella term production. As previously mentioned, the closest the Production of Culture Perspective comes to the concept of consumption is through the term market. As a line of research, the production perspective “focuses on the impacts on cultural production in a single market structure” (Peterson 1994, 167f.). Only in his later work, does he account for an impact of consumption on production by the use of his new term autoproduction, where cultural choices by specific population groups with specific lifestyles affect production outputs, linking production and reception theory (see 1994, 183).

Neo-Institutionalism does not pay too much attention to the production side either, and it mostly ignores the consumption side.3 However, the power of social cognition – that is, the group-oriented and taken-for-granted normativity of established patterns of behavior and attitudes – can be easily transferred to the consumption side. All members of organizations act in an institutionalized setting and thus use their cognitive and tacit knowledge as scripts, whether as producers or as consumers. In general, consumers or consumer organizations (such as consumer protection agencies) are not however, pivotal players in organizational sectors.

Cultural Institutions Studies understands cultural consumption – as does the Production of Culture approach – more as a production-decision issue than as a stand-alone element. From an arts organization’s point of view, consumption analysis is primarily a marketing issue, labeled as customer orientation, customer loyalty or public response (e.g., Vakianis 2006). Target group analysis is limited to the purpose of being more effective in finding demand for the output produced than an independent affecting factor of organizing arts. Zembylas (1997, 149–189) also pays attention to the role of art critics as a group of professional receivers, who contribute to public awareness of artworks and consequently influence to some degree consumer behavior.

Cultural distribution as a major element of the three middle‑range theories

Besides production, distribution is probably the most important element in the Cultural Diamond (see figure 6). This node encompasses the largest and most central area of the Production of Culture Perspective, being pivotal for organizing arts and culture as “marketing, distribution, exhibiting, inculcation, evaluation” (Peterson 1976, 10), for researching from the production perspective looking at “comparative market structures,” “market structures over time” and “gatekeeping” (see Peterson 1994), and for defining facets of production such as technology, law and regulation, industry structure, organizational structure and occupational roles (see Peterson and Anand 2004).

Distribution in Neo-Institutionalism focuses on the relational networks and commitments of organizations to their sector when, for example, connecting supply with demand in a vertical organizational sector (see Scott and Meyer 1991) or when dealing with accountability (see Meyer 1994).

Cultural Institutions Studies to a large extent does not have a single research field for cultural distribution. However, the framework conditions of distribution are dealt with in the sectors of production (conditions of production) and especially in the sector of societal factors (sociostructural conditions, cultural policy). As with the Production of Culture approach, Cultural Institutions Studies points out the importance of gatekeepers for the distribution of artists and their performances. Gatekeepers are those entities “that generate a relatively broad art public” (Zembylas 1997, 67, 198) and “that participate substantially in the formulation, dissemination, and enforcement of evaluations” (Zembylas 2006c, 27). Arts organizations are thus based on networks of cooperative activities that are shaped by distribution structures in addition to production conditions and demand.

3 Conclusion: Comparing the three middle-range theories

The three theories have been compared regarding the significance of social context and mediation of the main organizational components. In the Production of Culture Perspective, context is understood as six measurable relations between a social environment and arts objects, or genres. From an industrial sociology point of view, these six factors are regarded as opportunities or constraints for an industrial entrepreneur. The six facets of legal frameworks, technology, occupational roles, industry structure, organizational structure and markets are institutional realities and must all be observed when analyzing the success or failure, the emergence or decline of an artwork or an art genre. Cultural Institutions Studies displays some similarities to the Production of Culture Perspective by identifying institutional spheres that are comparable to the facets. In contrast, Cultural Institutions Studies is not prone to ideal type contexts, as it stresses that the contexts of artistic work vary so comprehensively that case studies cannot be easily accounted for in a few context categories or facets. Neo-Institutionalism pays close attention to interdependencies among organizations in the same sector, their density, their scale and the scope of networks (see Powell 1990), thus providing explanations for social cognition, isomorphism and legitimacy. Of all middle-range theories, it is Neo-Institutionalism that underlines the contextual importance of the organizational environment the most when discussing the multiple impacts of the organizational sector.

Finally, we would like to make some critical remarks about the concept of context. First, context is not just made up of features that are measurable and stable; second, analysis of context has to be limited to a few important aspects and layers; third, relevant contextual relations have to be theoretically and methodologically justified; and fourth, any context analysis is necessarily incomplete because a holistic understanding of the social surroundings, including all tacit aspects, is almost impossible to achieve. Therefore, while context analyses among all three middle-range theories have unavoidable limitations, they are tolerable.

The Cultural Diamond illustrates the relations of arts organization among the five groups of object, creator, distributor, consumer and society. The mediations among them shape and are shaped by the various meanings of art, their power and social effect, and the interference by social powers, structures and processes.

-

First, from the Production of Culture Perspective, cultural objects are symbolic goods produced in specialized industries. They are “very concrete elements such as books, paintings, scientific research reports, religious celebrations, legal judgments, etc.” (Peterson 1976, 165). Peterson argues that his approach is close to industrial sociology and focuses “on the more fluid and creative entrepreneurial form of organization” (Santoro 2008b, 46). The main research objects of Neo-Institutionalism are not (artistic) outcomes but (art) organizations. Cultural Institutions Studies defines its research objects very concretely as cultural industries and cultural industry products, for example, the music industry, the economic valorization of artistic goods or artistic attributions based on sociopolitical effects.

-

Second, from the Production of Culture Perspective context remains ambiguous because it may encompass everything from the global (e.g., for India and the national music industry, see Peterson and Anand 2004) to the local (e.g., for the impact of Manhattan neighborhoods on local styles of classical music concerts, see Gilmore 1987). Conversely, Neo-Institutionalism understands society very specifically as organizational sectors. Cultural Institutions Studies further extends the idea of society to different spheres, for example, policy, law and markets.

-

Third, from the Production of Culture Perspective and in Cultural Institutions Studies, production is everything from creation to evaluation. Neo-Institutionalism avoids the term, and most scholars of the field use the term entrepreneurs instead of producers.

-

Fourth, consumption has been largely neglected by the Production of Culture approach since as a market factor it is often subsumed under the production term, for example, as autoproduction. Neo-Institutionalism pays no attention to consumption. For Cultural Institutions Studies, consumption is mostly considered a marketing issue of a cultural industry. For all these theories, the interest in consumption is rather marginal.4

-

Fifth and finally, distribution as an element of organizing arts is of very high significance for the Production of Culture Perspective, as it includes all central activities of arts organization such as marketing, exhibiting, inculcation, evaluation and gatekeeping. For Neo-Institutionalism, distribution means solely the flow of resources and commitments in organizational sectors. Cultural Institutions Studies understands the area of distribution primarily as a condition of production (e.g., cultural policy, legal frameworks) and not as a stand-alone element.

All three middle-range theories help us understand the social organization of arts. They should be regarded as cognitive tools rather than ends in itself. None of these theories is preferable to the others; they all provide conceptual orientation, and their specific advantages or disadvantages depend on their specific application. As such a ranking of these theories would be counterproductive to their purpose, which is to achieve a deeper understanding of the various phenomena of arts organizations in social contexts.

Endnotes

-

The significance of relational sociology, particularly of Social Network Theory, for the study of the social organization of arts shows up intermittently in the works of the middle-range theories, but also in all three grand theories. We will revisit this topic as a future theoretical focus of the sociology of arts in the concluding chapter 10.↩︎

-

Especially the volatility of preferences generates a systemic uncertainty, which Richard Caves (2000, 3; see Zembylas 1997, 81) coins as the “nobody knows principle” of cultural industries.↩︎

-

A rare exception in sociological arts research is Walmsley (2012), who argues for a neo-institutionalist approach from the visitor side to explain artistic value in theater.↩︎

-

Peterson’s omnivore thesis (1992) was developed as a response to Bourdieu’s analysis of the formation of cultural taste and preferences, and not as a genuine development of the Production of Culture Perspective.↩︎