Rumya S. Putcha

Abstract: This chapter exposes the role of expressive culture in the rise and spread of late twentieth‐century Hindu identity politics. The author examines how Hindu nationalism is fueled by affective logics that have crystallized around the female classical dancer and have situated her gendered and athletic body as a transnational emblem of an authentic Hindu and Indian national identity. This embodied identity is represented by the historical South Indian temple dancer and has, in the postcolonial era, been rebranded as the nationalist classical dancer. The author connects the dancer to transnational forms of identity politics, heteropatriarchal marriage economies, as well as pathologies of gender violence. In so doing, the author examines how the affective politics of ‘Hinduism’ have functionally disembodied the Indian dancer from her voice and her agency in a democratic nation‐state. The author argues that the nationalist and now transnationalist production of the classical dancer exposes misogyny and casteism and thus requires a critical feminist dismantling.

How to cite

How to cite

Bibliographical note

Bibliographical note

Portions of this chapter originally appeared in Rumya S. Putcha, “The Modern Courtesan: Gender, Religion, and Dance in Transnational India,” Feminist Review 126 (2020): 54–73 and have been reproduced with permission.

About the author

About the author

Rumya S. Putcha is an assistant professor in the Institute of Women’s Studies and the Hugh Hodgson School of Music at the University of Georgia.

Introduction

In 1988, South Indian film director K. Viswanath (b. 1930) released a film entitled “Swarnakamalam” (Golden Lotus). Viswanath cast the beautiful and talented dancer‐actress Banupriya (b. 1967) as Meenakshi, the daughter of a high‐caste Hindu classical dancer. A product of her father’s training, Meenakshi is a gifted performer, but has no interest in leading the life of a classical dancer, which she sees as a dying, anachronistic profession. Her love interest in the film, Chandrasekhar, however, holds Meenakshi’s father in great esteem as a symbol of Indian religious—that is, Hindu—heritage. Throughout the film, this love interest acts as her conscience and encourages Meenakshi to realize that, as her father’s daughter, she embodies invaluable cultural knowledge. He implores her to see that modern India needs her to keep Hindu culture “alive”—to keep modernity from erasing cultural memory. By the end of the film, Meenakshi accepts an invitation to move abroad. As she prepares to board a plane and leave India for a new life in the United States, she realizes she is afraid of what she will lose by starting over there—i.e., everything she has ever known, especially her identity as a dancer. Rather than moving to America, she decides at the last second to stay in India, marry Chandrasekhar, and uphold her family’s high‐caste, Hindu identity by becoming a dancer‐teacher, like her father before her.

I was seven years old when Swarnakamalam was released and two years into my own initiation into Indian dance and vocal training. Swarnakamalam’s dramatization of gendered cultural transmission, symbolized by music, dance, and Brahminical Hindu identity, resonated deeply with my parents, who, like many upwardly mobile and dominant‐caste Indians, in the wake of the 1965 Immigration Act,1 had immigrated to the United States. I came to know the film well. Anytime I didn’t want to practice dance, my family would plop me in front of the television and make me watch it because, in many ways, Swarnakamalam offered me a path to follow, as a first‐generation immigrant to the United States and a transnational Indian and Hindu woman. Films like Swarnakamalam, which connect female dance and daughterhood to homeland, and homeland to upper‐caste Hindu identity, are vital in the Indian film industry more broadly since they capitalize on a stabilized understanding of the cultural formations that synonymize a democratic nation‐state, Hindu identity, and the gendered body.2

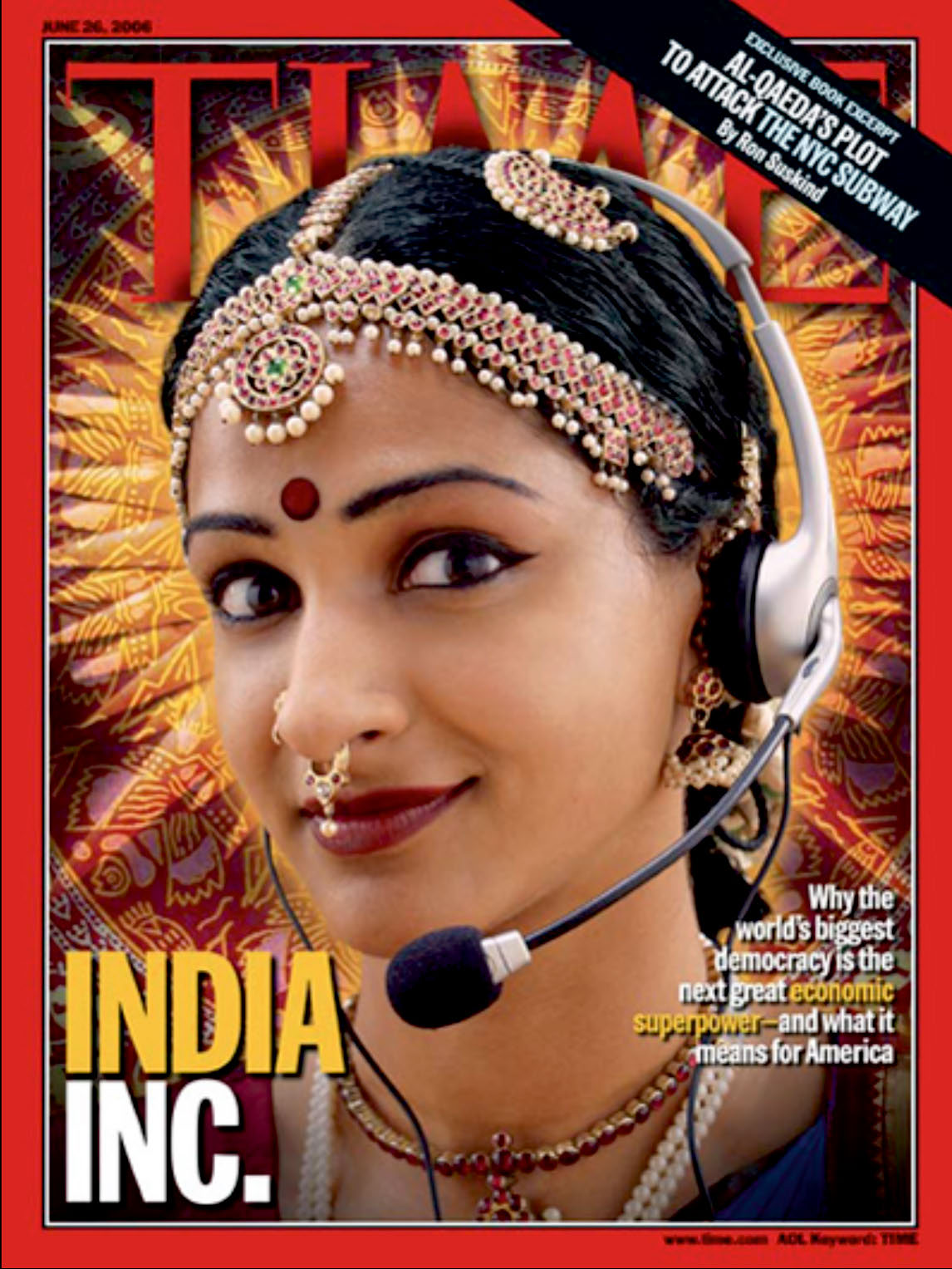

Figure 1: Cover of June 26, 2006, Time Magazine featuring an Indian classical dancer as a call‐center worker. Source: Time Magazine.

In this chapter, I take a closer look at the affective logics that have crystallized around the now iconic Indian classical dancer. I refer to her as a modern courtesan to capture the gendered and heteropatriarchal imperatives that have situated her as a global emblem of a transnational Indian identity, particularly in democratic and pluralistic North American settings. Culling together ethnography, film and media analysis, and feminist critiques, I trace the cultural formations which connect the romanticized Hindu temple dancer to the modern classical dancer and the fetishization of the female dancer to rape culture.3 I bring together transnational feminism,4 queer/affect theory,5 on the one hand, and a body of work on classical dance by dominant caste Hindus within postcolonial nationalism,6 gender, caste, democracy, and the Indian nation‐state,7 on the other hand, to critically examine how the affective politics of twenty‐first century postcolonial nationalism have curated and controlled the Indian, that is, female, dancing body.

The larger theoretical intervention I offer in this chapter is that the dancer and her body, even when understood as separable from music, is doing important political work. This work is particularly potent in pluralistic and democratic settings, where the expressive body, becomes a technological8 metonym for citizenship. First, I lay out a brief history of the rise of postcolonial Hindu identity politics—often glossed as Hindu nationalism or Hindutva—and its bodily discourses through gendered expression like dance, drawing particular attention to the way the body operates within affective attachments based on colonial epistemologies of religion in transnational South Indian dance cultures. I then connect such overdetermined ideologies of identity, religion, and nation, which are often understood to only exist in the Hindi heartland, but have been and continue to be memorialized in Telugu films like Swarnakamalam and in visual cultures more broadly, to ethnographic research on classical dance in India as well as the United States. In making these connections between film cultures, visual cultures, and dance studios, I locate myself and my ethnographic access as a transnational Indian woman and dancer. In so doing, I draw on South Asian-American feminist scholarship that engages with South Asian racial formations9 as well the postcolonial feminist scholarship of Lila Abu-Lughod, Saba Mahmood, Aihwa Ong, and Rajeshwari Sundar Rajan.10 Taken as a whole, this body of feminist scholarship has lodged a collective critique against cultural relativism and the kinds of Euro-American imperialist intellectual projects that equate orientalized women and their bodies with postcolonial religious nationalism.

To unsettle a facile reading of the Indian classical dancer‐as-nation, in this chapter I make a case for viewing visual and performance culture as part and parcel of simultaneously right‐wing Hindu nationalist agendas as well as colonial‐derived and global North liberal logics. By framing the political and affective economy of the Indian classical dancer as that of a tension between Hindutva or an uncomplicated multiculturalism, I suggest that we understand her as a version of what Sara Ahmed has theorized as a “sticky” symbol, which reveals both religious and patriarchal chauvinism as well as colonial and Orientalist racism.11 As I expand my lens to think critically about gender, race, and transnational bodies, I am drawing from the kinds of feminist praxis and everyday interventions championed by bell hooks and Sara Ahmed.12 Indeed, in drawing together ethnographic work, film, and visual culture to think critically and self‐reflexively about gender and religion, I take to heart hooks’s and Ahmed’s respective advice on living a feminist life.

The Female Body in the Postcolonial Indian Archive

In India’s case, independent statehood, achieved in 1947, unleashed violent and toxic religious sectarianism. The British, notorious for a divide‐and-conquer strategy in colonial administration, championed a brand of religious identitarianism that ultimately amounted to the partition of British India into a Hindu India and a Muslim Pakistan. The affective attachment to the new Indian nation as a Hindu woman and goddess (see Figures 2 and 3) further circumscribes the relationship between religious identity politics, nationalism, and gender, both in India and in all the spaces and places where India is evoked.13 The Indian classical dancer and her counterpart in film cultures has animated and mobilized identity politics in ways that have become increasingly urgent with the ascendance of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his rhetoric of “India First.”

Figures 2 and 3: Trans World Air advertisements (1960s) featuring a female Indian classical dancer as a symbol of Indian tourism. Artist credit: David Klein.

In postcolonial India, the Hindu female dancer is India (see Figures 2 and 3). Moreover, this iconic and fetishized Hindu dancer emerges from the South Indian context, in the areas known today as Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, respectively, where she is said to have danced in temples. It is by now a truism among those who study the body in India that the South Indian classical dancer, as an essentialized and visual archetype, exposes dual imperatives of Hindu nationalism and transnationalism that we could not otherwise see. For the role she has played in championing Hindu hegemony in and as India, the figure of the female dancer has loomed large within scholarship on nation, religion, and women in India over the past sixty years. Much of this literature has examined the nationalist reinvention of the arts and the overdetermination of Sanskrit textual authority to examine the role of the mytho‐historical figure of the courtesan, often reduced to the categories of devadasi in the South or tawaif in the North.14 Indeed, feminist scholarship from India on dance and music has noted the uneven and reductive historiography of the courtesan from south India in particular as a symbol of a postcolonial and transnational India, and, problematically, a cultural ambassador for a hegemonic and casteist Hindu nation‐state.15

The modern courtesan, much like her historical counterpart, is an object of desire, but a source of social dystopia. She is saturated with extra‐cultural meaning in the transnational and highly mediated spaces in which Indian identity circulates today: from cinema and satellite television16 to visual culture like advertisements and cosmopolitan standards of beauty. Courtesanship in this equation points to a consolidation of performance training, especially music and dance, steeped as these arts are in a decidedly Hindu identification, into a highly marriageable young woman or daughter in transnational India. Dance training, especially in transnational North American settings, is integral to Indian identity because it signals religious identification as well as regimes of value framed as “beauty” and thus functions as a commodity in marriage economies.17 Thus, the commodification of the expressive and athletic female body must be seen as crucial to the Indian identity globally, synonymous as the modern courtesan is with the racial and heterosexual identity she represents visually.

The modern courtesan recasts the rejected qualities of an improperly sexualized woman to new domains of citizenship and choice built on the principles and behaviors of conjugal wifehood. The choice to be appropriately sexual, in particular, is valorized by both young women and the dominant discourses of post‐feminism. In South Asia, this “appropriate” behavior is still limited to the confines of patriarchy, and specifically marriage. But as Lucinda Ramberg and Srimati Basu so eloquently observe,

the efficiency of marriage as a unit makes systematic privileges within it invisible; we may only be able to discern these points of fracture such as divorce, which reveals that not only does “gender structured marriage involve women in a cycle of socially caused and distinctly asymmetric vulnerability,” but that women “are made vulnerable by marriage itself.”18

Heteronormative marriage or wifehood were and still are goals for the vast majority of the women with whom I have danced over the past thirty years, in India as well as the United States, even as they acknowledge that marriage will not make them happy. Or as one fellow dancer once exclaimed in exasperation, “I know ninety percent of marriages are unhappy, but we do it anyway!” Affective attachments, especially the expression of pleasure and identification through and by a relationship to the dancing body in popular television and film provide a crucial lynchpin, which explains this “anyway”19 attitude. In the ethnography I offer below, I examine how, in the dance studio, for example, the comportment of the female body to the rules of heteronormativity is fundamental to the daily experiences of patriarchal order: rape culture. Put another way, the logics of gender in the dance studio require the sidelining of anything resembling choice, much less consent.

The policing of women’s bodies as a symptom of rape culture—a hallmark of South Asian feminist critique—has only come under greater scrutiny in the aftermath of the high‐profile 2012 rape case, known generally as Nirbhaya, in New Delhi. The argument that has been maintained by many apologists for the rapists involved in the case rests on the widely held belief that there are certain affective behaviors that women, especially young women, can adopt in certain spaces. When such spaces are mutually agreed upon (e.g., a dance stage), rape culture, as a facet of patriarchy, remains intact. This narrow understanding of affect relies upon what scholars of sexual violence refer to as the “perfect victim” syndrome. In the case of Nirbhaya, the media storm surrounding the case relied on a rhetoric that the victim could have been any Indian woman. Feminists across India have pointed out that Nirbhaya only generated protests because she represented a young woman whom Indians were willing to see as their daughter—that is, a Hindu, high‐caste, yet‐to-be‐married woman.20 Considering an Indian woman is raped every twenty‐two seconds,21 the flashpoint that Nirbhaya ignited speaks to a very specific and privileged kind of womanhood that sparks outrage. Simply put, Jyoti (the victim’s legal name), a Hindu citizen who had every potential of fulfilling a middle‐class heterosexual dream of a career, husband, and children, did not deserve to be raped. The fact that she was “punished” by an old India (for this is the euphemism for sexual violence against modern cosmopolitan women) enraged feminists who had championed the very kinds of choices that Jyoti had made so far in her young life.

But this celebration of choice lies at the heart of much of the feminist discourse in and on South Asia and is more generally associated with what are otherwise lumped together as third‐wave feminist approaches. An enduring lightning rod in the contemporary global South feminist conversation has been and continues to be the limits of liberal subject formation when it comes to what Mahmood has named in her work as the “politics of piety.”22 In the case of Indian classical dance, it is increasingly important that we interrogate who gets to choose a sovereign gender or sexual identity, and what that might even look like for women within religious affective cultures and their attendant political economies. In posing these questions, I am consciously and carefully avoiding anything resembling judgement on what qualifies as feminist or anti‐feminist, especially when women choose to express or abdicate religious identification. Rather, I work towards developing analytical tools, including vocabulary, that can capture “the critical differences between women who are upholders of patriarchal norms and those who fight these norms.”23

Dance Studios and Sexual Violence

As I’m leaving class today with my new dance friend Priya and we’re walking to get an auto, she tells me that I shouldn’t get too close to Mastergaru24. That it looks bad for me to be talking to the “staff” too much. She says that I may not have noticed, but everyone was watching when I was asking questions, and that the politics are just so bad, I have to be careful about getting too close. I’m guessing she’s saying this (for my own good, of course; she’s a sweet kid) because people who talk too much seem like they are kissing up and then things get complicated and problems begin when everyone assumes you’re sleeping with the teacher and then they expect more money. She apparently had some sort of bad experience with one of the teachers harassing her. Now that I know about her family situation and that she is the only child of a poor but Brahmin family, and a daughter at that, it all makes sense why she would be so cautious.25

I have spent much time over the course of my life training at formal dance institutes in India, but none with as much nostalgia, for me at least, as the ones in Chennai. The most prominent Kuchipudi training center in Chennai (hereafter the KC26), was founded with nationalist goals: a commitment to spreading the message that classical Indian dance was only and always Hindu, and such history was best articulated by and through gender‐normative femininity. As a genre, Kuchipudi historians’ particular commitment to Brahminical propaganda has endured for generations now and has been especially effective transnationally. 27

More so than any other dance style that is nominally understood as “classical,” Kuchipudi, as an idiom, was developed by and through film cultures.28 The most commercially successful South Indian films over the course of the twentieth century featured Kuchipudi choreographers and choreography almost without exception (see, for example, Sankarabharanam).29 Furthermore, by the late twentieth century, the films which traveled the farthest were those which spoke to the mass exodus of South Indians in the post-1965 era and featured Kuchipudi in name as well as movement vocabulary. These films, like Swarnakamalam, relied on a highly problematic nostalgia for a more hierarchical and more fundamentalist society and, in many cases, named dance schools like the KC in the film itself. Indeed, if one looks at Indian films as a whole, including commercial Hindi films, from the final decades of the twentieth century, there is a distinct pattern of Hindu identity politics and its connections to beautiful, athletic women who are talented dancers that becomes apparent.30

Though many have noted the obviously troublesome anti-Muslim and heteropatriarchal aspects of Hindu nationalism that are valorized through film cultures,31 relatively little has been said about the misogynistic and casteist dynamics that circulate under the banner of classical dance. A number of feminist scholars have critiqued the reproduction of colonial epistemologies of gender in anthropology as a discipline and ethnography as a methodology.32 What is otherwise known as “participant‐observation” exposes certain racialized, gendered, and transnational dynamics that would otherwise remain invisible were it not for the fact that although I am a product of the American academy, I read as an Indian and Hindu woman in the dance studio. It was only after a white female American friend of mine, Erin, came to visit and joined me one day at the KC that I could see how my racial identity, vis-à-vis hers, affected my time in the studio.

Class and rehearsals begin and I’m startled and amused by how Master takes to Erin and, by extension of his obsession with her, how he really drills me today. He basically gives me his undivided attention. We alternate between dance and talk. His English isn’t great so he keeps yelling at me to translate. He makes a huge fuss about my form, especially my aramandi33 today. He tells me to sit and sit and sit to such a point that I’m on my toes. Now, he doesn’t call this by its true name in terms of shastra (textual authority) so I’m pretty confused when he tells me to keep sitting even though my heels have come up. We work through some adavus (basic steps) and I’m totally exhausted. He seems to enjoy Erin’s audience and he gets into a bit of a soliloquy with her comparing the East and West. He babbles on about the Vedas and Bharata and generally the history and belief‐based systems of the East (India in specific, of course) in comparison to the rational empirical‐inquiry driven West. To drive this point home, he gives her, through me, an example. He’s holding his stick that he uses to conduct class and puts it behind his back. He says that in India he could keep the stick behind his back and tell someone (a student?) that the stick is there and if he is a person of greater knowledge then he would never have to show the stick to prove its existence. In America, he would need to show the stick to prove it was really there. It’s bizarre, it’s like he’s insulting the West (represented by Erin) in this moment, but uses me as a tool to accomplish that insult. Lesson learned for me, don’t bring any more of my White friends along unless I want all kinds of uncomfortable attention.34

I had been a student and a Kuchipudi dancer familiar with such spaces for over twenty‐five years when the interaction narrated above took place. In that time, I had learned a few important things about how institutional dance spaces operate. I had learned that the men who ran the studio space were generally to be feared, or at the very least, regarded warily. I learned such lessons from a constellation of experiences over the years, ranging from full‐on verbal abuse and body shaming to microaggressions that made it clear that dancers from the US were seen as less than those from India. Interestingly though, it was always made abundantly clear that American students were essential to the financial health of a dance institution like the KC. It is common knowledge among dancers that NRI (non‐resident Indian) dancers (all American without exception) study at the KC and even perform in productions through a sort of “pay to play” system. As many students know, there are often wealthy parents back in the States who usually bankroll tours in the US, purchasing a lead role for their college‐age (or younger) daughter along the way.

My own entry into the KC during my fieldwork, despite my research status at that point, was marked by a collision of patriarchy and payment in a striking and, quite frankly, disturbing manner. A telling example of what I came to see as the marriage of neoliberalism and patriarchy occurred on my very first day. Now, as a Telugu Brahmin woman, I was at an incredible advantage to move and work in that studio space—I spoke the language and could blend in easily. Yet, the very things that granted me unfettered access also shackled me in some fascinating ways. For example, I was informed I could not enroll myself. Despite being nearly 30 years old at that moment, I required the permission and blessings of either a parent or my husband to enroll in classes. To be fair, this was as much a condition of the dance school as it was one of my natal family. You see, dance studios like the KC have a reputation. Every Telugu family is at least vaguely familiar with the concern that their daughter is going to be manipulated into sex if she is left alone with her male dance guru. The KC has experienced many a scandal over its history and in each case, it is the young dancer who is blamed for “allowing” such sexual indiscretion to occur. Leaving aside the absurdity of holding teenage girls responsible for the sexual predation of the male gurus for the moment, it suffices to say, I was equal parts wary and aghast that I required my father’s presence to conduct my research.

My father was mostly there to do his duty, but as is often the case, as a dad, he had very little experience with what happens behind the scenes in dance schools. Mothers are generally the emissaries in such settings, despite patriarchy’s stranglehold, but also because of it. My father and I arrived together, ready to formally pay our respects and request my admission to the school as a sishya (student). As is customary, I had brought tambulam (a ceremonial Hindu offering) and was to be formally presented to the guru. I bought a shirt for the guru and fabric for a blouse for his wife, two bananas and one orange, and sandwiched ₹1,116 between the fruit and clothes. After handing the gift over, I touched my new teacher’s feet as an act of my obeisance.

The surreptitious gifting of money within the practice of tambulam has always struck me as odd, but it is consistent across nominally Hindu settings. The same practice is observed, for example when one seeks the blessing of a priest. The exchange of currency, though ostensibly meant to curry favor or luck in a temple setting, takes on a very different meaning at an institution like the KC. To be sure, the exchange of money and financial support in general is something that flies under the radar in the transnational and diasporic Hindu classical dance scene. During my time in Chennai, I came to see the impact of NRI wealth as particularly important to any understanding of how religious identity operates for Indian (Hindu) women who consider themselves dancers.

During my time in Chennai, there were larger conversations about who, besides NRIs that is, could afford such training and exposure, and what other kinds of social capital could and would be accumulated in the process. A Stateside example of how Hindu female bodies signify presented itself clearly to me throughout my training in Houston, since every summer my guru invited artists from India to workshop us on “how to look more Indian.” The training we young American‐born Indian women received during such summers was intense and often a test of physical and athletic ability in ways I did not experience during the rest of the year. The takeaway message for those of us who stuck through long eight‐hour days in the studio was that dancers in India were better, more athletic; their bodies better trained, more rigorously trained, at the very least. We were encouraged to adjust our diets, to incorporate yoga into our training regimen, and to practice even more.

In 2006, in response to such discourses of relative value, an organization named Yuva Bharati was founded in the Bay Area with the explicit aim of promoting US-based Indian classical dancers. The impetus for the founding of such an organization, as described to me, was to fight the perception that dancers from India were “better” dancers. As one informant and founding member explained, “Our daughters train long and hard here, but they will never be recruited to perform for high‐profile events. Those engagements only go to dancers from India. We are trying to create a space that supports dancers trained in the States and stop making them feel like their art is only valued second to the dancers from India.”35 It is important to note that over the decade of programming this organization has presented, the fare has been consistent and homogenous. The only styles of dance presented are those understood as Hindu and classical. To date, there has yet to be a male dancer in their lineup.36

I observed how such value judgments worked across transnational borders and within broader Hindu nationalist imperatives in Chennai. “The Season”37 in Chennai occurs in December and during my fieldwork I had a chance to see how the KC levied its wealth and resources to put its best foot forward during the most prestigious performance time slots on the most hallowed stages, like the Madras Music Academy. During rehearsals, I observed the interactions between the wealthy NRIs and the dancers from India who didn’t live in Chennai, but converged upon the stern concrete rehearsal space over the course of the week leading up to the performance.

I was awestruck by the contrast between the two sets of dancers. The dancers from India were lithe: their bodies strong and sinewy and pliable in ways the American dancers were not. I caught myself idealizing the Indian bodies and their aesthetic appeal in a way that reminded me of why Yuva Bharati existed in the first place. My eyes were drawn to one particular dancer and the way she executed one particular movement: a movement which was the cause of much consternation among dancers in my home studio in Houston, Texas.

Figures 4 and 5: Tham‐that-tha‐din-ha, dancer: Yashoda Thakore, 2020. Photo by Rumya S. Putcha.

The adavu or step is colloquially known as sit‐stretch, but it’s official name or nadaka in the KC vernacular is tham‐that-tha‐din-ha.38 Physically, this movement, as a sequence in the KC training regimen is a test of athletic ability. Only the strongest‐bodied dancers can execute the entire sequence in which there are multiple renditions of this movement with differing hand‐gestures. This sequence tests core and quadricep strength in a way that dancers know well, but for which we never explicitly train.

That day, as I watched a group of dancers from the United States rehearse alongside a group of dancers from the subcontinent, I could see the distinction between the two sets of bodies. There was a fluidity to the way the female Indian dancers executed this movement especially in comparison to the way their male counterparts did. The American dancers, I realized, looked more like the men. Their torsos were straighter and the labor and power of their legs was apparent. In other words, the women from the United States read as more masculine in that space because the strength and conditioning of their bodies was visible.

Our guru, who was leading the rehearsal, could see the difference too, and began correcting the American dancers, telling them they looked “like men” in their expression of this particular adavu. He mocked them and I felt my face grow hot with shame and anger as he looked to the other India‐based dancers for support in treating these young women as though their inability to affect a specific femininity was a sign of some great failing. I felt especially for the young dancers in this group, particularly the youngest who was no more than 14. I had gotten to know this young woman well, and I knew that she was not only a dancer, but also a competitive tennis player in the United States. Her body betrayed her tennis training, especially in the way she was able to recruit her quadricep strength and push up from the ground with force. Her athleticism betrayed her dancerly role in that space, and unapologetically demonstrated the sheer muscle strength of her legs. She was a dancer, to be sure, but she was also an American‐born sportswoman: her body was powerful and it showed. She looked so confused and hurt in that moment when Master scolded her—she was executing the movement perfectly and she was too young to understand that it was her gender expression that had come under fire.

Dance, Gender, and Religion

Only male bodies are entitled to demonstrate power at the KC; this was something I came to understand well. Despite performing the exact same movements to the exact same tempo, female dancers at the KC are expected to mask the labor taking place by and through their bodies. This masking process is often glossed as lasyam or grace, something that is never required of a male body making the same movements. The inverse of lasyam in dance vernacular is tandavam, which loosely translates as vigor. Put simply, lasyam requires all the same movements as tandavm but with softened edges.

Functionally, the softening of the body’s athletic output is most visible in the initiation of motion and the seamlessness between the start and ending of movement phrases. This masking process extends in ways both subtle and explicit and often includes body shaming against women and commentary like what I heard that day. In the studio, it usually results in telling the American women dancing that they do not dance like Indian women; that their femininity is somehow lacking. Over the course of my life, especially during my time in Chennai, I came to understand which parts of my body needed to be leveraged more or less to mark my gender identity and, in turn, how this gender work translated to heteronormative Hindu affect.

In Chennai, the part of the body that indexed gender and sexuality most acutely was my hips. The positioning of my hips demonstrated my gender and the movement of my hips did the work of eliciting sexuality. Male dancers are not expected to over‐exaggerate their hips, but in a fascinating and revealing performance at an annual tourism festival, I observed a male guru of mine dancing with a woman in unison. During this performance, as in many others where a man and a woman dance together (see below), the male body position mirrors the female.

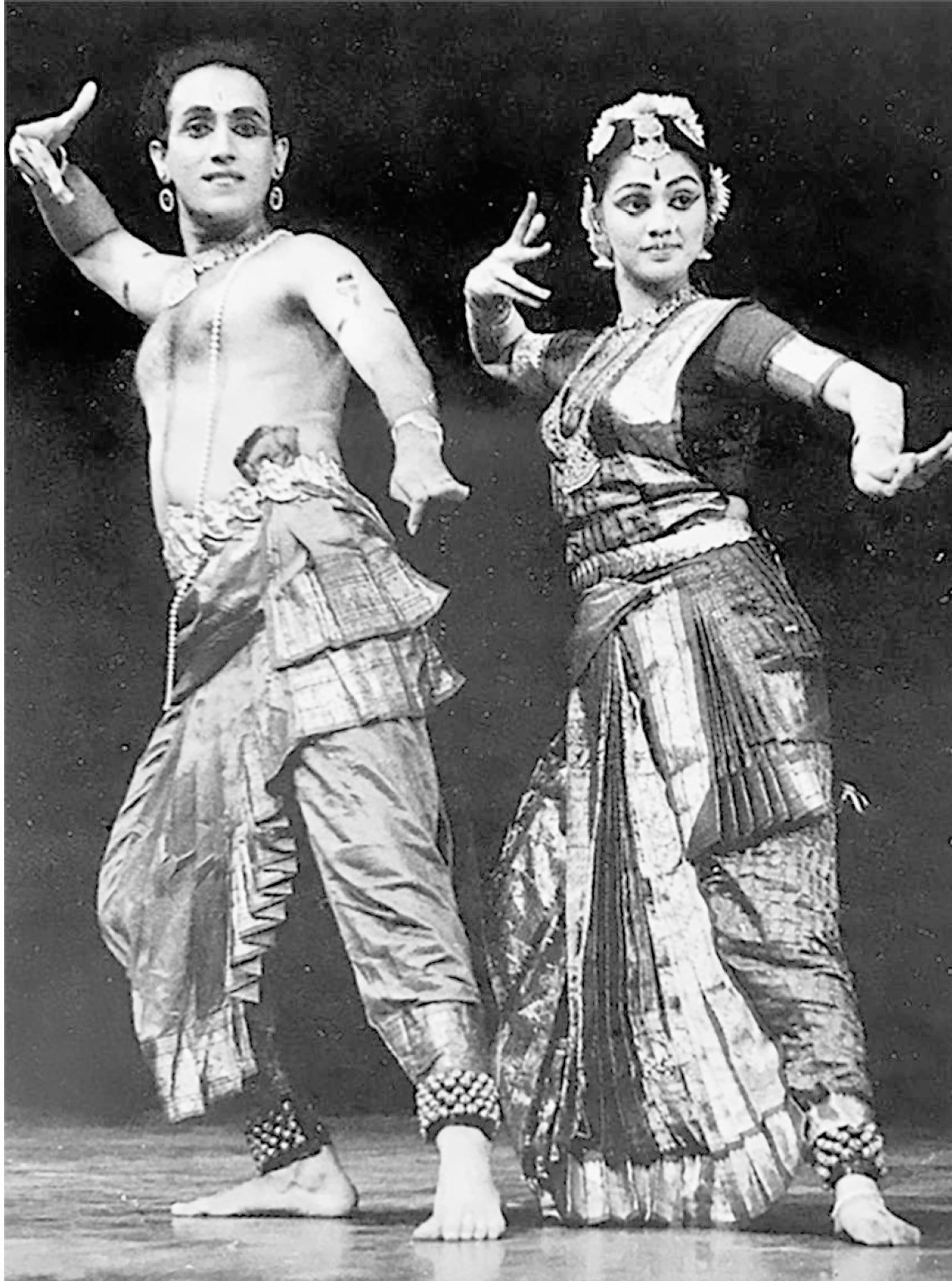

Figure 6: M.V.N. Murthy and Priya Sunderesan. Photo Courtesy: Avinash Pasricha.

I didn’t think much of their synchronicity at the time; if anything, such an aesthetic was to be expected. Female body comportment is the default setting in nominally Hindu dance styles, especially Bharatanatyam and Kuchipudi. After the performance, however, as I congratulated my guru, he asked me quietly, betraying a sense of shame and self‐consciousness, “do I look too much like a woman when I dance?” Shocked at the vulnerability of his question at the time, I did what I thought would seem most supportive and batted away his concern. I quickly and overzealously reassured him that his masculinity remained fully intact and that he needn’t worry about seeming emasculated. His dance was graceful and beautiful and that was what made him a man.

Yet, that question undeniably raised a number of questions about what kinds of work gender is doing in spaces that are so fully saturated with sexual affect and religiosity inscribed on cis‐gendered female bodies. His concern was particularly paradoxical since the style he was presenting, Kuchipudi, is best known for its tradition of female impersonation. This legacy, known as stri vesam, connects across performance idioms and, as many scholars of theatre and dance have noted, is a symptom of hyper‐patriarchy, Brahminism, and homo/transphobia under the logics of Hindu nationalism.39 The practice of female impersonation is central to narratives of Kuchipudi’s contribution to Indian cultural memory and relies on an axiom in Hindu nationalism: Brahmin men adjudicate on how female bodies should look and act. In the process of such legislation, cis‐gender female comportment becomes codified and stylized. I, like a generation of dancers before me, learned how to affect womanhood from women who learned from men who built their artistic careers seducing audiences as women. The KC maintains this kyriarchical pedagogy, particularly in the affecting of cis‐female heterosexuality. These structures of oppression, especially around the idea of what kinds of behavior translate into desirable dancerly affect, reveal a great deal about what kinds of work gender performance does on and off stage. Simply put, classical dance cultures, by virtue of their primary gendered affective purpose, are, by definition, examples of religious nationalism and its transnational consequences. Furthermore, the concomitant discourses of aspirational Hindu womanhood à la wifehood, which appear through performance cultures, require us to see the production and control of sexuality as legitimated sex work.40 Wifehood, by virtue of its implication in institutional dance cultures, is simply a destination and the journey is for sale.

Conclusion

As a way to bring my own web of cogitation on dance, womanhood, and religion to a close, I returned to what, in many ways, started it: I watched Swarnakamalam again. This time as a grown woman, an academic who has slowly disaggregated a lifetime of dance training from its ethnographic potential, and the heuristics of diasporic film‐viewing from the nostalgia and desire it used to (and sometimes does still) evoke. At the end of the film, before Meenakshi decides to forgo a life abroad with all the chances and risks it offers, she reads a letter that Chandrasekhar has written her. In it, he exhorts her to “be happy.” All he asks is that if she ever thinks of him when she dances, that she remembers who she really is. The message, that happiness is achievable, but at odds with an intact sense of identity, while somehow romantic at an earlier time in my life, now only speaks to a deep and abiding sense of pressure that many women—not only dancers—experience under the reductive and intractable identity politics of postcolonial and transnational forms of nationalism. We are offered two options, to adhere to or to abdicate, both of which require us to understand a Hindu identification and its expression through dance as something forced upon us.

Sara Ahmed once observed how happiness is used to justify oppression and that feminist work over the past century has primarily attempted to disabuse us of the idea that working towards happiness leads to it. If being a happy Indian woman means training one’s body and emotions to look and feel and uphold Hindu heteropatriarchy, so goes the narrative at least, what kinds of feminist interventions are available to us? I am reminded and indebted here to Saba Mahmood’s work, which has demonstrated that women can and do find personal and political ways to resist, even under extreme conditions. And so I have come to see the Indian dancer as an athlete and her athleticism as a form of resistance to Hindu nationalist imperatives, on the one hand, and a symptom of challenging uncomplicated notions of democratic plurality in transnational settings, on the other. The standard framings of her athletic body as a sexualized icon can and do lead to new forms of rape culture and objectification, this is true, but for the women I have danced with over the years, both in India and in the US, dance and its physicality provides a powerful sense of bodily autonomy for the individual who, like the tennis‐player-dancer I met in Chennai, relishes the feeling of her body and its power. In the end, this is how body endures as a site of resistance for the individual, in spite of, or perhaps precisely because of, broader and often contradictory political imperatives.

Endnotes

1 The Hart-Cellar Act, or Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, phased out the national origins quota system that had been in place since 1921. Whereas previous to the Act, immigration to the United States from anywhere besides the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Germany was severely limited, this legislation instituted a preference system that focused on immigrants’ skills and family relationships with citizens or residents.

2 See Rachel Dwyer, Filming the Gods: Religion and Indian Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2006); Dwyer, Pleasure and the Nation: The History, Politics and Consumption of Popular Culture in India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006); Sangita Gopal and Sujata Moorti, Global Bollywood: Travels of Hindi Song and Dance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008); Ashis Nandy, ed., The Secret Politics of Our Desires: Innocence, Culpability, and Indian Popular Cinema (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998); Madiraju M. Prasad, Ideology of the Hindi Film: A Historical Construction, 6th ed. (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2001); Jyotika Virdi, The Cinematic Imagination: Indian Popular Films as Social History (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2003).

3 Rape culture, a phrase coined by second‐wave feminists in the United States, requires us to see that rape is not simply about sex, but about the normalization of sexism, patriarchy, and heteronormative gendered behavior; see Noreen Connell and Cassandra Wilson, Rape: The First Sourcebook for Women (New York: New American Library, 1974); Susan Brownmiller, Against our Will: Men, Women and Rape (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1975).

4 See M. Jacqui Alexander and Chandra Talpade Mohanty, eds., Feminist Genealogies, Colonial Legacies, Democratic Futures (New York: Routledge, 1997); Inderpal Grewal and Caren Kaplan, Scattered Hegemonies: Postmodernity and Transnational Feminist Practices (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006 [1994]); Grewal, Transnational America: Feminisms, Diasporas, Neoliberalisms (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005); Saba Mahmood, Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012); Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Feminism without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003); Jasbir K. Puar, Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007); Amanda Lock Swarr and Richa Nagar, eds., Critical Transnational Feminist Praxis (Albany: SUNY Press, 2010).

5 See Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004); Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006); Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010); Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011); Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006).

6 See, e.g., Pallabi Chakravorty, Bells of Change: Kathak Dance, Women, and Modernity in India (Kolkata: Seagull Books, 2008); Indira Peterson and Davesh Soneji, eds., Performing Pasts: Reinventing the Arts in Modern South India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2008); Avanthi Meduri, “Nation, Woman, Representation: The Sutured History of the Devadasi and Her Dance” (Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1996); Janet O’Shea, At Home in the World (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2007); Davesh Soneji Unfinished Gestures: Devadasis, Memory, and Modernity in South India (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011); Priya Srinivasan, Sweating Saris: Indian Dance as Transnational Labor (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012).

7 See Anjali Arondekar, For the Record: On Sexuality and the Colonial Archive (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009); Uma Chakravarti, Thinking Gender, Doing Gender: Feminist Scholarship and Practice Today (New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2016); Partha Chatterjee, “The Nationalist Resolution of the Women’s Question,” in Recasting Women: Essays in Indian Colonial History, ed. Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid (New Delhi: Kali for Women, 1989), 233–53; Anupama Rao, ed., Gender, Caste, and the Imagination of Equality (New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2018); Sharmila Rege, “The Hegemonic Appropriation of Sexuality: The Case of the lavani Performers of Maharashtra,” Contributions to Indian Sociology 29, no. 1–2 (1995): 23–38; Rajeswari Sunder Rajan, Real and Imagined Women: Gender, Culture, and Postcolonialism (London: Routledge, 1993); Sunder Rajan, Signposts: Gender Issues in Post-Independence India (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001); Sinha, “Gender in the Critiques of Colonialism and Nationalism: Locating the ‘Indian Woman,’” in Feminism and History, ed. Joan Wallach Scott (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 477–504; Sinha, Specters of Mother India: The Global Restructuring of an Empire (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006); Tanika Sarkar, Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation: Community, Religion, and Cultural Nationalism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010).

8 Here I am relying in part on Michel Foucault’s formulation of “technologies of the self,” which “permit individuals to effect by their own means or with the help of others a certain number of operations on their own bodies and souls.” Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault, ed. Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman, and Patrick H. Hutton (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), 88.

9 See Gayatri Gopinath, Impossible Desires: Queer Diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005).

10 See Lila Abu-Lughod, “Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving? Anthropological Reflections on Cultural Relativism and Its Others,” American Anthropologist. 104, no. 3 (2002): 783–90; Mahmood, Politics of Piety; Aihwa Ong, “Colonialism and Modernity: Feminist Re-Presentations of Women in Non-Western Societies,” Inscriptions 3–4 (1988): 79–93; Ong, “State versus Islam; Malay Families, Women’s Bodies, and the Body Politic in Malaysia,” American Ethnologist 17, no. 2 (1990): 258–76; Sunder Rajan, Real and Imagined Women (1993).

11 Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 120.

12 bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2015); Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

13 Speaking specifically about Bengal, Partha Chatterjee once famously dubbed the gendered identity politics of postcolonial India “The Women’s Question”; see Chatterjee, “The Nationalist Resolution of the Women’s Question,” 233–53.

14 See, e.g., on South India and the devadasi, Avanthi Meduri, “Bharatha Natyam—What Are You?” Asian Theatre Journal 5, no. 1 (Spring 1988): 1–22; Amrit Srinivasan, “Temple ‘Prostitution’ and Community Reform: An Examination of the Ethnographic, Historical and Textual Context of the Devadasi of Tamil Nadu, South India” (Ph.D. diss., Cambridge University, 1984); Srinivasan, “Reform and Revival: The Devadasi and Her Dance,” Economic and Political Weekly 20, no. 44 (1985): 1869–76; Davesh Soneji, Unfinished Gestures: Devadasis, Memory, and Modernity in South India (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011). On North India and the tawaif, see Pallabi Chakravorty, Bells of Change: Kathak Dance, Women, and Modernity in India (Kolkata: Seagull Books, 2008) and also Shweta Sachdeva, “In Search of the Tawa’if in History: Courtesans, Nautch Girls and Celebrity Entertainers in India (1720s–1920s)” (Ph.D. diss., SOAS, University of London, 2008).

15 See Sharmila Rege, “The Hegemonic Appropriation of Sexuality: The Case of the Lavani Performers of Maharashtra,” Contributions to Indian Sociology 29, no. 1–2 (1995): 23–38.

16 See, for example, Purnima Mankekar, Screening Culture, Viewing Politics: An Ethnography of Television, Womanhood, and Nation in Postcolonial India (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999); Mankekar and Louisa Schein, Media, Erotics, and Transnational Asia (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).

17 Women with dance and music training are understood as more marketable on the marriage market. See Reginald and Jamila Massey, The Music of India (New Dehli: Abhinav Publications, 1996): 76.

18 Srimati Basu and Lucinda Ramberg, eds., Conjugality Unbound: Sexual Economies, State Regulation, and the Marital Form in India. (New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2015): 12.

19 A version of Lauren Berlant’s Cruel Optimism (1).

20 Krupa Shandilya, “Nirbhaya’s Body: The Politics of Protest in the Aftermath of the 2012 Delhi Gang Rape,” Gender & History 27, no. 2 (2015): 465–86; Mark Phillips et al., “Media Coverage of Violence against Women in India: A Systematic Study of a High Profile Rape Case,” BMC Women’s Health 15, no. 3 (January 22, 2015), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-015-0161-x.

21 Calculated based on a standard reporting failure rate of one in ten. See B.L. Himabindu, Radhika Arora and N.S. Prashanth, “Whose Problem Is It Anyway? Crimes against Women in India,” Global Health Action 7, no. 1 (2014), https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23718.

22 Mahmood, Politics of Piety.

23 Mahmood, Politics of Piety, X.

24 A term used to address a male guru or teacher. Female instructors are not referred to with this honorific.

25 Excerpt from the author’s fieldnotes.

26 To protect the privacy of the individuals associated with the dance school I will be using pseudonyms.

27 See Rumya Putcha, “Dancing in Place: Mythopoetics and the Production of History in Kuchipudi,” Yearbook for Traditional Music 47 (2015): 1–26.

28 See Katyayani Thota, “Stage to Screen, and Back: A Study of the Dialogue between Kuchipudi and Telugu Cinema” (Ph.D. diss., University of Hyderabad, 2016).

29 Sankarabharanam, directed by Kasinadhuni Viswanathan (1980, India).

30 See Usha Iyer, “Stardom Ke Peeche Kya Hai? / What Is behind the Stardom? Madhuri Dixit, the Production Number, and the Construction of the Female Star Text in 1990s Hindi Cinema,” Camera Obscura 30, no. 3 (2015): 129–59, https://doi.org/10.1215/02705346-3160674.

31 See, e.g., Sikata Banerjee, Gender, Nation and Popular Film in India: Globalizing Muscular Nationalism (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017); Gopinath, Impossible Desires; Sanjeev Kumar, “Constructing the Nation’s Enemy: Hindutva, Popular Culture and the Muslim ‘Other’ in Bollywood Cinema,” Third World Quarterly 34, no. 3 (2013): 458–69; Madhavi Murty, “Representing Hindutva: Nation, Religion and Masculinity in Indian Popular Cinema, 1990 to 2003,” Popular Communication 7, no. 4 (2009): 267–81.

32 See Lila Abu-Lughod, “Can There Be a Feminist Ethnography?” Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 5, no. 1 (1990): 6–27; Linda Alcoff, “The Problem of Speaking for Others,” Cultural Critique 20 (1992): 5–32; Trinh T. Minh‐ha, Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009 [1989]); Kirin Narayan, “How Native Is a ‘Native’ Anthropologist?” American Anthropologist 95, no. 3 (1993): 671–86; for a further critique of ethnographic methods and feminist interventions see Kamala Visweswaran, Fictions of Feminist Ethnography (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994).

33 Aramandi is loosely understood as a half‐sitting baseline posture in most South Indian classical dance forms.

34 Excerpt from the author’s fieldnotes.

35 Personal correspondence with the author.

36 See http://yuvabharati.org. The amount of NRI wealth that is funneled into representing India in the United States through Indian dance is on the ascent, especially in places like the San Francisco Bay Area. See, for example, Silicon Andhra, a 501(c)(3) organization that supports dance teachers from India to travel to the US and train young women. This organization recently expanded into a degree‐granting institution. See https://www.siliconandhra.org/en/.

37 The Season, also referred to as the Music Season, takes place every December in Chennai and lasts about six weeks. During this period, there are increases in international tourism, with many visiting to see the music and dance performances held at local art houses known as sabhas. See the newly instituted website for the most recent schedule, http://www.chennaidecemberseason.com, accessed December 29, 2016.

38 There is an equivalent to this adavu in Bharatanatyam, though it is executed differently, with a twist.

39 See, i.e., Kathryn Hansen, “Stri Bhumika: Female Impersonators and Actresses on the Parsi Stage,” Economic and Political Weekly 33, no. 35 (1998): 2291–300; Hansen, “Making Women Visible: Gender and Race Cross-Dressing in the Parsi Theatre,” Theatre Journal 51, no. 2 (1999): 127–47; Davesh Soneji, “Performing Satyabhama: Text, Context, Memory and Mimesis in Telugu-Speaking South India” (Ph.D. diss., McGill University, 2004).

40 See Subir K. Kole, “From ‘Veshyas’ to ‘Entertainment Workers’: Evolving Discourses of Bodies, Rights, and Prostitution in India,” Asian Politics & Policy 1, no. 2 (2009): 255–81; Jyoti Puri, Woman, Body, Desire in Post-Colonial India Narratives of Gender and Sexuality (New York: Routledge, 2002).

References

Abu-Lughod, Lila. “Can There Be a Feminist Ethnography?” Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 5, no. 1 (1990): 6–27.

Abu-Lughod, Lila. “Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving? Anthropological Reflections on Cultural Relativism and its Others.” American Anthropologist 104, no. 3 (2002): 783–90.

Ahmed, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004.

Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

Ahmed, Sara. The Promise of Happiness. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010.

Ahmed, Sara. Living a Feminist Life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Alexander, M. Jacqui, and Chandra Talpade Mohanty, eds. Feminist Genealogies, Colonial Legacies, Democratic Futures. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Ahmed, Sara. “Cartographies of Knowledge and Power: Transnational Feminism as Radical Praxis.” In Critical Transnational Feminist Praxis, edited by Amanda Lock Swarr and Richa Nagar, 23–45. Albany: SUNY Press, 2010.

Alter, Joseph. Yoga in Modern India: The Body Between Science and Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Alcoff, Linda. “The Problem of Speaking for Others.” Cultural Critique 20 (1992): 5–32.

Arondekar, Anjali. For the Record: On Sexuality and the Colonial Archive. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009.

Banerjee, Sikata. Gender, Nation and Popular Film in India: Globalizing Muscular Nationalism. Abingdon: Routledge, 2017.

Basu, Srimati, and Lucinda Ramberg. Conjugality Unbound: Sexual Economies, State Regulation, and the Marital Form in India. New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2015.

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011.

Brownmiller, Susan. Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1975.

Chakravarty, Uma. Gendering Caste Through a Feminist Lens. Calcutta: Stree, 2003.

Chakravarty, Uma. Thinking Gender, Doing Gender: Feminist Scholarship and Practice Today. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2016.

Chakravorty, Pallabi. Bells of Change: Kathak Dance, Women, and Modernity in India. Kolkata: Seagull Books, 2008.

Chatterjee, Partha. “The Nationalist Resolution of the Women’s Question.” In Recasting Women: Essays in Indian Colonial History, edited by Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid, 233–53. New Delhi: Kali for Women, 1989.

Connell, Noreen and Cassandra Wilson. Rape: The First Sourcebook for Women. New York: New American Library, 1974.

Dwyer, Rachel. Filming the Gods: Religion and Indian Cinema. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Dwyer, Rachel. Pleasure and the Nation: The History, Politics and Consumption of Popular Culture in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1, translated by Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage Books, 1990 [1976].

Foucault, Michel, Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman, and Patrick H. Hutton. Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988.

Gopal, Sangita, and Sujata Moorti, eds. Global Bollywood: Travels of Hindi Song and Dance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Gopinath, Gayatri. Impossible Desires: Queer Diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005.

Grewal, Inderpal. Transnational America: Feminisms, Diasporas, Neoliberalisms. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005.

Grewal, Inderpal, and Caren Kaplan. Scattered Hegemonies: Postmodernity and Transnational Feminist Practices. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006 [1994].

Hansen, Kathryn. “Stri Bhumika: Female Impersonators and Actresses on the Parsi Stage.” Economic and Political Weekly 33, no. 35 (1998): 2291–300.

Hansen, Kathryn. “Making Women Visible: Gender and Race Cross-Dressing in the Parsi Theatre.” Theatre Journal 51, no. 2 (1999): 127–47.

Himabindu, B.L., Radhika Arora and N.S. Prashanth. “Whose Problem Is It Anyway? Crimes against Women in India.” Global Health Action 7, no. 1 (2014). https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23718.

hooks, bell. Black Looks: Race and Representation. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Iyer, Usha. “Stardom Ke Peeche Kya Hai? / What Is behind the Stardom? Madhuri Dixit, the Production Number, and the Construction of the Female Star Text in 1990s Hindi Cinema,” Camera Obscura 30, no. 3 (2015): 129–59. https://doi.org/10.1215/02705346-3160674.

Kole, Subir K. “From ‘Veshyas’ to ‘Entertainment Workers’: Evolving Discourses of Bodies, Rights, and Prostitution in India,” Asian Politics & Policy 1, no. 2 (2009): 255–81.

Kumar, Sanjeev. “Constructing the Nation’s Enemy: Hindutva, Popular Culture and the Muslim ‘Other’ in Bollywood Cinema,” Third World Quarterly 34, no. 3 (2013): 458–69.

Mahmood, Saba. Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Mankekar, Purnima. Screening Culture, Viewing Politics: An Ethnography of Television, Womanhood, and Nation in Postcolonial India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999.

Mankekar, Purnima, and Louisa Schein. Media, Erotics, and Transnational Asia. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012.

Massey, Reginald, and Jamila Massey. The Music of India. New Dehli: Abhinav Publications, 1996.

Meduri, Avanthi. “Bharatha Natyam—What Are You?” Asian Theatre Journal 5, no. 1 (Spring 1988): 1–22.

Meduri, Avanthi. “Nation, Woman, Representation: The Sutured History of the Devadasi and Her Dance.” Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1996.

Minh‐ha, Trinh T. 2009. Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009 [1989]

Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. Feminism without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003.

Murty, Madhavi. “Representing Hindutva: Nation, Religion and Masculinity in Indian Popular Cinema, 1990 to 2003.” Popular Communication 7, no. 4 (2009): 267–81.

Nandy, Ashis. The Secret Politics of Our Desires: Innocence, Culpability, and Indian Popular Cinema. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

Narayan, Kirin. “How Native is a ‘Native’ Anthropologist?” American Anthropologist 95, no. 3 (1993): 671–86.

Ong, Aihwa. “Colonialism and Modernity: Feminist Re-Presentations of Women in Non-Western Societies.” Inscriptions 3–4 (1988): 79–93.

Ong, Aihwa. “State Versus Islam; Malay Families, Women’s Bodies, and the Body Politic in Malaysia.” American Ethnologist 17, no. 2 (1990): 258–76.

O’Shea, Janet. At Home in the World. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2007.

Peterson, Indira, and Davesh Soneji, eds. Performing Pasts: Reinventing the Arts in Modern South India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Phillips, Mark, Mostofian, Fargol, Jetly, Rajeev, Puthukudy, Nazar, Madden, Kim, and Bhandari, Mohit. “Media Coverage of Violence against Women in India: A Systematic Study of a High Profile Rape Case.” BMC Women’s Health 15, no. 3 (January 22, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-015-0161-x.

Prasad, Madiraju M. Ideology of the Hindi Film: A Historical Construction. 6th ed. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Puar, Jasbir K. Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007.

Puri, Jyoti. Woman, Body, Desire in Post-Colonial India Narratives of Gender and Sexuality. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Putcha, Rumya S. “Between History and Historiography: The Origins of Classical Kuchipudi Dance.” Dance Research Journal 45, no. 3 (2013): 1–20

Putcha, Rumya S. “Dancing in Place: Mythopoetics and the Production of History in Kuchipudi.” Yearbook for Traditional Music 47 (2015): 1–26.

Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt. “In Search of Begum Akhtar: Patriarchy, Poetry, and Twentieth-Century Indian Music.” World of Music 43, no. 1 (2001): 97–137.

Ramaswamy, Sumathi. The Goddess and the Nation: Mapping Mother India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010.

Rao, Anupama, ed. Gender, Caste, and the Imagination of Equality. New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2018.

Rege, Sharmila. “The Hegemonic Appropriation of Sexuality: The Case of the lavani Performers of Maharashtra.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 29, no. 1–2 (1995): 23–38.

Sachdeva, Shweta. “In Search of the Tawa’if in History: Courtesans, Nautch Girls and Celebrity Entertainers in India (1720s–1920s).” Ph.D. diss., SOAS, University of London, 2008.

Sarkar, Tanika. Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation: Community, Religion, and Cultural Nationalism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

Shandilya, Krupa. “Nirbhaya’s Body: The Politics of Protest in the Aftermath of the 2012 Delhi Gang Rape.” Gender & History 27, no. 2 (2015): 465–86.

Sinha, Mrinalini. “Gender in the Critiques of Colonialism and Nationalism: Locating the ‘Indian Woman.’” In Feminism and History, edited by Joan Wallach Scott, 477–504. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Sinha, Mrinalini. Specters of Mother India: The Global Restructuring of an Empire. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

Soneji, Davesh. “Performing Satyabhama: Text, Context, Memory and Mimesis in Telugu-Speaking South India.” Ph.D. diss., McGill University, 2004.

Soneji, Davesh, ed. Bharatanatyam: A Reader. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Soneji, Davesh. Unfinished Gestures: Devadasis, Memory, and Modernity in South India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Srinivasan, Amrit. “Temple ‘Prostitution’ and Community Reform: An Examination of the Ethnographic, Historical and Textual Context of the Devadasi of Tamil Nadu, South India.” Ph.D. diss., Cambridge University, 1984.

Srinivasan, Amrit. “Reform and Revival: The Devadasi and Her Dance.” Economic and Political Weekly 20, no. 44 (1985): 1869–1876.

Srinivasan, Priya. Sweating Saris: Indian Dance as Transnational Labor. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012.

Sunder Rajan, Rajeswari. Real and Imagined Women: Gender, Culture, and Postcolonialism. London: Routledge, 1993.

Sunder Rajan, Rajeswari. Signposts: Gender Issues in Post-Independence India. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

Swarr, Amanda Lock, and Richa Nagar, eds. Critical Transnational Feminist Praxis. Albany: SUNY Press, 2010.

Thota, Katyayani, “Stage to Screen, and Back: A Study of the Dialogue between Kuchipudi and Telugu Cinema.” Ph.D. diss., University of Hyderabad, 2016.

Virdi, Jyotika. The Cinematic Imagination: Indian Popular Films as Social History. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2003.

Visweswaran, Kamala. Fictions of Feminist Ethnography. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994.

Filmography

Sankarabharanam, 1980, directed by Kasinathuni Viswanath. Distributed by Poornodaya Movie Creations.

Swarnakamalam, 1988, directed by Kasinathuni Viswanath. Distributed by Poornodaya Movie Creations.