A Challenge of Writing in Musique Mixte from 1958 to 1960

Elena Minetti

Elena Minetti

How to cite

How to cite

Outline

Outline

“Writing is historically the first technique for manipulating time”1 (Kittler 1993: 183; English translation in Krämer 2006: 99). With this phrase, Friedrich Kittler considered writing to be the earliest technique for arranging and reversing events happening on the time axis. In this view, writing is a practice that has the potential to (re)order streams of data through spatial coordinates on two-dimensional surfaces. For this theoretical assumption, Kittler gives a practical explanation, drawn precisely from musical writing practice: He quotes the use of a retrograde of the ‘Bach motif’ – consisting of the notes B flat, A, C, B natural (in German musical nomenclature: B A C H) – which appears in the Fugue BWV 898 as the reversal of the composer’s name (H C A B) (Kittler 1993: 185).

Transferring these considerations to a musicological perspective, musical inscriptions constitute lasting manifestations of ephemeral phenomena progressing in time which, by virtue of being written, can be simultaneously visualised, correlated at a glance and also manipulated and rearranged, as in the ‘Bach motif’ example (see Krämer 2006; Celestini et al. 2020).

Building on these ideas, this essay focuses on a central function of musical notations, which is closely related to writing’s capacity to manipulate and visualise time: The synchronisation of musical events – an issue that in standard western notation, for example, has been encoded through the vertical superposition of simultaneous musical voices. More concretely, this study investigates how writing practices aimed at synchronising sounds became particularly complex and challenging for the composers when recorded electroacoustic sounds entered instrumental performance.

Indeed, in the so-called musique mixte, whose first experiments can be traced back to the early 1950s, (at least) two different temporalities coexist: on the one hand, the temporality of the live concert, on the other hand, the temporality of the previously recorded track resounding through loudspeakers. A definition of musique mixte – a term that is quite nebulous and can be misleading (Sallis et al. 2018: 5–7) – is proposed by Vincent Tiffon in his doctoral thesis (Tiffon 1994) and later in numerous articles (id. 2005, 2013):

[Musique mixte] is concert music that combines instruments of acoustic origin with sounds of electronic origin, the latter produced in real time – during the concert – or fixed on electronic media and projected via loudspeakers at the time of the concert. (Tiffon 2005: 23)

The definition focuses on the combination of acoustic instruments played at the time of the performance and sounds of electronic origin that can be produced live or can be recorded and played back during the concert. Musique mixte in its early form, which combines live musicians with pre-recorded electronic parts, confronts the coexistence of a temporality produced in the past and recorded once and for all and a temporality alive and produced during the concert. Certainly, when a pre-recorded music resonates in performance it becomes alive again, yet the productive origin of that part will remain anchored to a past musical phenomenon.

Having in mind the etymological meaning of the verb ‘to synchronise’ – that is from the Ancient Greek συγχρονίζω, which literally means ‘to be contemporary with, to be at the same time of’ – the title of this paper might sound oxymoronic. Synchronising indicates indeed that two or more phenomena have to happen together, as the prefix syn- specifies, in a single chronos, in a unified temporality (see Jordheim 2017: 59). The phrase ‘synchronising different temporalities’ intends to underscore the challenge of writing to coordinate musical phenomena that are produced at different times and which then, however, coexist in the performance and in the performance score, too.

The synchronisation of the electronic and acoustic dimensions of musique mixte is an issue that scholars studying this genre must inevitably address (Cont 2012; Scaldaferri 2002; Blondeau 2017). This essay proposes to identify by comparative analysis some essential features of the composers’ writing strategies to accomplish the task of making the synchronisation of musical temporalities visible. This topic will be examined by comparing the published scores of four musique mixte works, composed between 1958 and 1960: Analogique A et B (1958–59) by Iannis Xenakis, Rimes (1958–59) by Henri Pousseur, Transición II (1958–59) by Mauricio Kagel, and Kontakte (1958–60) by Karlheinz Stockhausen.2 The writing strategies adopted in the four scores will be highlighted, taking into consideration the compositional experiences and aesthetic motivations that led to the creation of these works. Some archival materials show how the hybrid configuration of sound production in the mixte ensembles had a great impact on the forms of writing used during the compositional process and also during the preparation of the performance, which was sometimes closely followed by the composers themselves. In the final performance scores, composers were faced with the challenge of how to annotate the human interaction with a recorded sound reality, which is (generally) static and only capable of a non-human, machine-like form of interaction.

At the end of the 1950s, there were no standardised rules involved in finding a form of writing for coordinating the live performance with the delayed time of “fixed sounds” – to use the term coined by Michel Chion (Chion 1991) – and/or recordings during the performance, and that left some space for composers’ notational and graphical creativity. Among the works considered, some of their performance scores contain minimal synchronisation instructions, while others use various notational forms, including actual transcriptions of recorded events. To macroscopically classify these differences, the concept of density is used as a parameter indicating the amount of information related to the synchronisation of instrumental and electroacoustic parts. Scores such as Xenakis’s Analogique A et B and Kagel’s Transición II show how the synchronising function of music writing can be expressed through a few essential notational signs, that is, through a low density of instructions. Instead, the scores by Pousseur for Rimes and by Stockhausen for Kontakte use more detailed graphic and notational strategies.

Synchronising through a Low Density of Notational Inscriptions

Analogique A et B by Xenakis

As the title suggests, Analogique A et B is a twofold piece, also in the compositional genesis of its two parts: The instrumental one for nine string instruments, indicated with the title Analogique A, was composed in 1958, while the electronic one, Analogique B for sinusoidal sounds, was produced one year later, first in a monophonic format during the summer of 1958 at Hermann Scherchen’s studio in Gravesano, and then with a stereophonic disposition of loudspeakers at the studio of the GRM (Groupe de Recherches Musicales) in Paris (Harley 2004: 17). Analogique A et B results from the superposition of the two compositions and was premiered in this final configuration in June 1960 at the Festival de la Recherche, organised by the RTF (Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française) in Paris. As stated in a review by Edmund J. Pendleton for The New York Herald Tribune, the title of the concert in which Analogique A + B3 was premiered without great success was The Return of the Interpreter, alluding to the performer’s “uselessness during mechanical experimentation” (Pendelton 1960). Instead, it proposed compositions that brought the instrumental performers back on stage, letting them interact with recorded parts.

The only published score related to Analogique A et B concerns the instrumental part and was published by Éditions Salabert in 1968 under the title Analogique A: partition d’orchestre. Despite the absence of a published score-like document for the electronic part, this partition d’orchestre contains significant information regarding the relationship between the instrumental and electronic components of the piece. First of all, it is clearly stated in the introduction to the score that “it is highly desirable that [Analogique A] should be performed to the accompaniment of the Analogique B complementary sound tape” (Xenakis 1968). In the same text, Xenakis describes how in both parts of the work “sounds were chosen statistically in arbitrary ranges of frequency, intensity and density. These ranges change in accordance with the transitional probabilities which follow a series of consequential events (the Markov series)”.

Analogique A et B are indeed applications of the Markovian stochastic theory, which is illustrated in detail in the second chapter of his Musique formelles (Xenakis 1963: 57–131). Already in 1954 Xenakis began to use probability distributions in the orchestra piece Pithoprakta (1955) and to experiment with probability calculations for musical composition – which two years later he would call “stochastic music” (Luque 2009). In Analogique A et B he added to the stochastic distribution of musical events the Markovian theory, “introducing a memory during the chaining of probabilistic states. […] [The complex reasoning] develops the notion of ‘frames’, i.e., temporal units defined by the parameters of pitch, duration, dynamics and density, which follow one another by means of Markov processes.” (Solomos 2017). In Analogique B Xenakis introduced, along with the Markovian stochastic theory, experimentations of his “hypothesis” of the granularity of sound: “All sound is made up of small bodies. Thus a ‘grain’ of sound can be defined approximately as a sound sinusoidal form and a given intensity which has a duration of the ‘thickness of the present’” (Xenakis 1968).

The juxtaposition of the two works was not decided by Xenakis programmatically at the beginning of the compositional process. It happened later. Although the works were conceived with analogous compositional mechanisms, they were thought of as distinct universes – a palpable consideration already at the first listening.4 Explaining Xenakis’s quite sparse production of musique mixte – besides Analogique A et B this includes only Kraanerg (1969) and Pour la Paix (1981) – Makis Solomos explains how Xenakis “postulates the autonomy of the universe of electroacoustic music. In this sense, he considers – following Varèse – that mixity [mixité] is a very delicate matter, which should be used with restraint.”5 (Solomos 2017: 163). In Analogique A et B, it seems indeed that the events on tape are interpolated with the instrumental parts without developing any real fusion, dialogue or transitions. A synchronisation is almost circumvented, even in the musical notation.

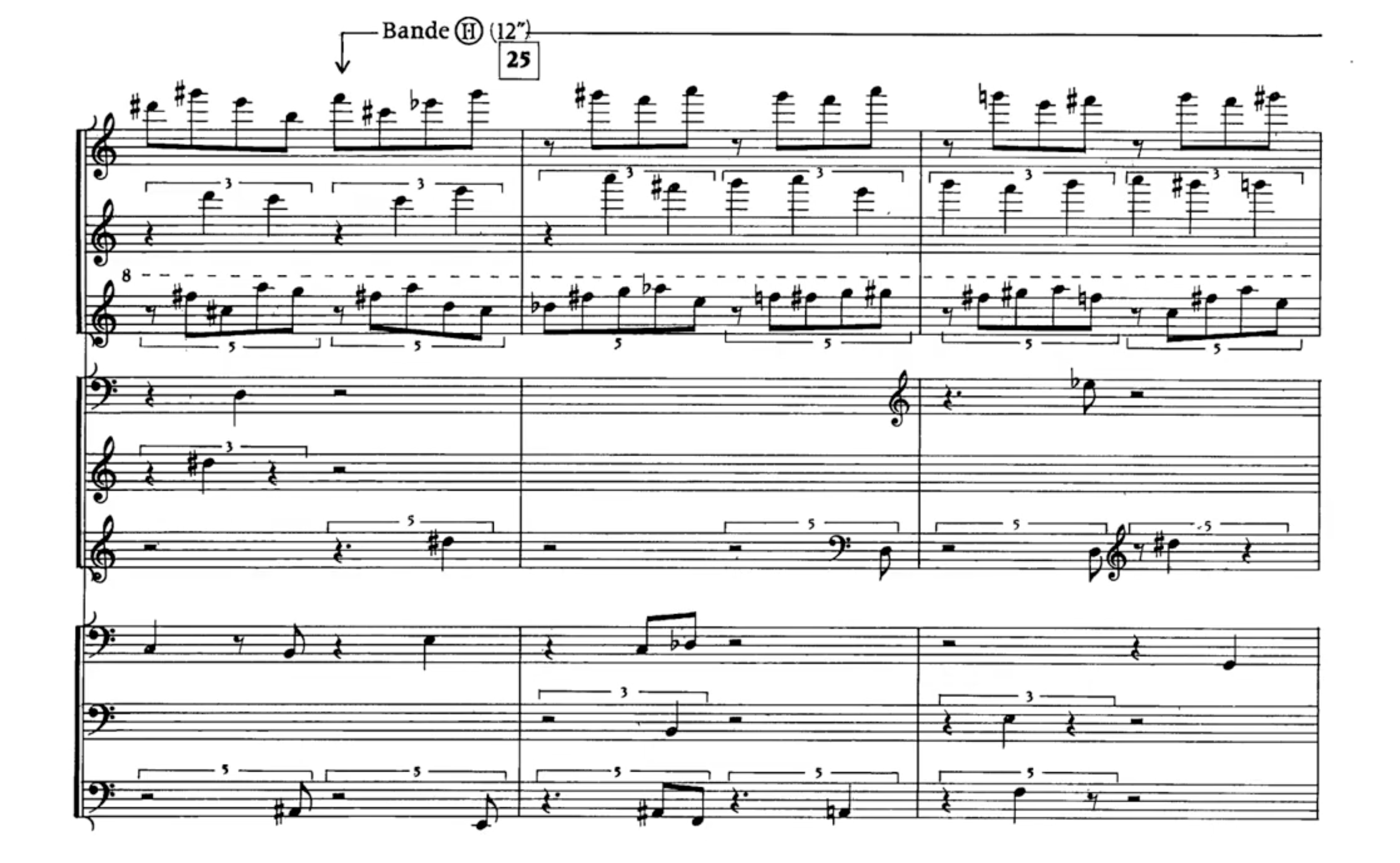

The visual configuration of the score clearly manifests the attempt to distinguish the two sonic layers. As can be seen from the reproductions of the score (Figures 4.1 and 4.2), Analogique A is written in standard western notation, while the starting points of the electronic interpolations of Analogique B are indicated by arrows and their durations in seconds, a chronometric style of time notation, mostly accompanied by fermatas of the instruments (see Figure 4.1). In the few instances when there is an overlap of the two parts, no actual electronic part is written, but a line represents its presence (see Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.1: Iannis Xenakis, Analogique A, orchestra score, p. 3, detail, Durand Salabert Eschig.

Not referring specifically to this composition, Vincent Tiffon argues that the principle of interpolations, already previously used by Bruno Maderna in Musica su due dimensioni (1952) and by Edgard Varèse in Déserts (1954) allows composers to elegantly circumvent the question of synchronisation (Tiffon 1994: 213). The synchronisation of acoustic and electronic dimensions in the early attempts of this genre indeed presented itself as a challenge, yet Xenakis’s choice, as brilliantly explained by Agostino Di Scipio, reveals deeper aesthetic motivations than eluding a musical problem:

The close encounter of the two sonic worlds allows us to make “a sensorial and structural comparison” (Xenakis 1971: 31) of two non-identical manifestations of the same compositional process. The same is presented as different, projected on different time-scales. […] In other words, by preserving the surface difference, Xenakis pointed to the manifestation of a more profound identity. (Di Scipio 2005: section 3.8)

In Analogique A et B the temporalities of the two universes converge in the listening experience, through remembering what has just been heard and what is being listened to, perhaps leading to the recognition of the same internal logic (i.e., a Markovian stochastic process) that has generated them.

Figure 4.2: Iannis Xenakis, Analogique A, orchestra score, p. 5, detail, Durand Salabert Eschig.

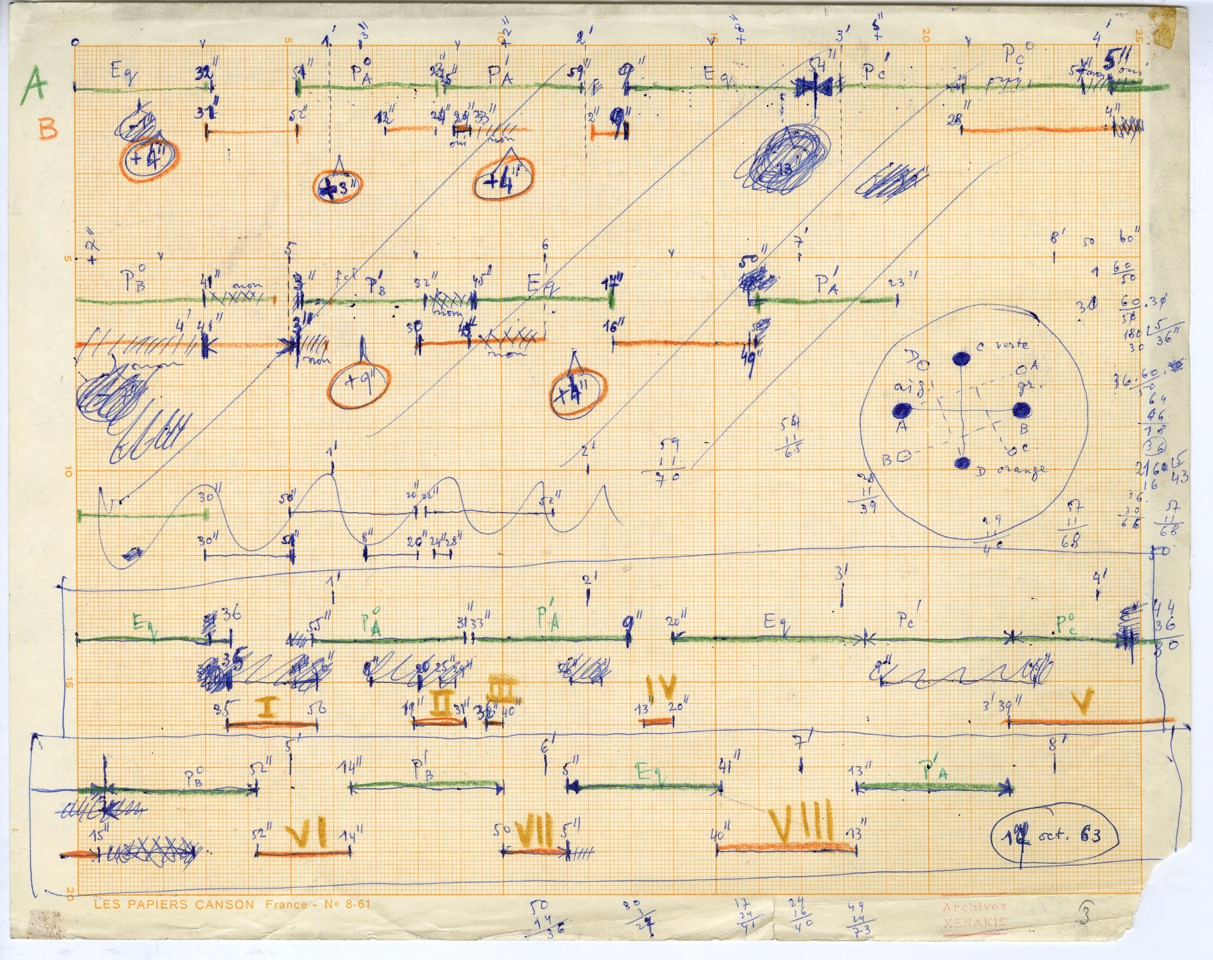

A need for synchronisation of the two parts is not at the heart of the compositional idea, though. In a sketch, dated “14. oct 63” (thus subsequent to the premiere) Xenakis gives a compact and schematic overview of the interlocking plan between the two parts.

On a millimetre sheet (see Figure 4.3), in addition to sketching a layout (circled) indicating the spatial distribution of the sound sources in the concert hall, Xenakis writes down three synchronisation diagrams of Analogique A et B: The first one is crossed out; the second one, only partially sketched, is struck through with a wavy line, and the last is the definitive one and is re-squared. In this diagram the x-axis, in which each millimetre corresponds to one second, represents time. Xenakis provides chronometric indications: six centimetres equal a minute, seconds are given at the beginning and end of each section. Line segments represent the sections of the instrumental part A (the upper lines) and those of the electronic part B (lower lines), which are specified by Roman numerals (I to VIII).6 This sketch testifies to how, even after the premiere, the synchronisation of the two parts continued to be a significant issue that had to be established, perhaps for future performances of the work, since the music score had not yet been published by Éditions Salabert.

Figure 4.3: Iannis Xenakis, Analogique A et B, sketch, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 5-5, p. 5.

Transición II by Kagel

Some similarity to Analogique A et B concerning the form of writing chosen to fulfil the synchronising function are traced in Transición II by Kagel. His encounter with electronic music in autumn of 1957 was for him the introduction to a “new musical time” (Kagel 1962: 15). Working on his first electronic composition Transición I for tape, he began “researching some relations between musical material and its temporal formation.”7 (ibid.). A reflection on temporality also forms the basis of Transición II for piano, percussion and two tapes, which despite the name has no obvious similarity with the previous work.8

The score – published by Universal Edition in 1963 – is conceived for a pianist and a percussionist who produces sounds directly on the strings of a grand piano. Some sections must be recorded beforehand (tape 1); some, if the technical conditions can guarantee a satisfactory result, should be recorded live during the performance on a second tape (tape 2) conceived and played back later in a shortened form, i.e., with its duration halved, equal to a third or a quarter of the durations of the original sections. Kagel refers to these as ‘structures’, but without modifying either the pitch or the duration of the sounds (id. 1963: 4). The composer states that three different layers overlap timewise:

While the interpreters always play in the present, they simultaneously record fragments for the future; these fragments, in turn, become the past when, later, they are made audible through loudspeakers in the hall. (Kagel quoted in Schwartz 1973: 115)

Despite the impressive variety of notational forms used in this work, such as action notation, traditional notation and graphic notation, the instructions to synchronise the three temporal layers in the final score and in particular the resulting interaction between the two tapes and the two musicians are quite minimal. Indeed, Kagel fixes some line segments at the bottom of some pages (which correspond to structures that interpreters must choose in their entirety), indicating the beginning and the end of any tape activities. This is the only information to tell the tape operator when to start the playback of tape number 1 and the recording or the playback of tape number 2 (see Figure 4.4).

Since the performers have the freedom to choose the order in which to perform the various parts of the piece (although a set of rules is prescribed which governs their choices),9 these lines are the only possible form of writing to indicate a recording or a playback. For this reason, a written form of exact synchronisation fixed in the score once and for all remains elusive.

Figure 4.4: Mauricio Kagel, Transición II, Structure 20 C, Universal Edition London Ltd.

Similar to the consideration of archive materials of Xenakis’s Analogique A et B, some sketches relating to Kagel’s supervision of performances of Transición II also clearly reveal that each performance requires a prior elaboration – including the synchronisation – of the concrete version of the variable piece. On several pages kept in the Mauricio Kagel Collection at the Paul Sacher Stiftung and dated from 1959 to 1960 (thus prior to the printed score in 1963) the composer jotted down some synchronisation drafts. In these notes, often written on so-called Band Begleitblätter (tape accompanying sheets), or pre-printed templates generally used for tracking the studio recording work, there are several annotations concerning the synchronisation of ‘ejecución’ (performance) and ‘bandas’ (tapes). In the diagram on a millimetre sheet reproduced here (see Figure 4.5), Kagel notes the final synchronisation of the composition sections, for the recording session for Time Records in New York in December 1960 with David Tudor (piano), Christoph Caskel (percussion), Mauricio Kagel and Earle Brown (sound engineers).10

Figure 4.5: Mauricio Kagel, sketch for the synchronisation of Transición II for Time Records, New York 1960, Paul Sacher Stiftung, Mauricio Kagel Collection.

In the diagrammatic graph, the x-axis represents the temporal succession, in which each centimetre is equivalent to one minute. Although the entrances to certain sections are only roughly indicated in the diagram with arrows, Kagel precisely specifies with chronometric indications at what point in time these sections enter: section B 35 at 3ʹ55ʹʹ, B 8–9 at 7ʹ40ʹʹ, A 4 at 14ʹ30ʹʹ and B 25 at 15ʹ30ʹʹ for a total of 17ʹ30ʹʹ. The y-axis represents the three types of sections A, B and C, which Kagel refers to in the introduction to the score as “three types of structure” (Kagel 1963: 2). In total there are 21 structures in the piece (nine of type A, seven of type B and finally five of type C). According to certain rules explained in the introduction, performers must choose which structures to play for a total duration of no less than ten minutes (Kagel 1963: 2–4). Furthermore, Kagel explains that on the first tape, B or C structures should be recorded before the performance, while on the second tape, A or C structures should be recorded during the performance. This diagram – quite similar to the Xenakis sketch described above – shows the necessity of working out a performance score during the preparation to visualise the concrete order of the sections including their synchronisation.

Synchronising through a High Density of Notational Inscriptions

Rimes by Pousseur

The genesis of Rimes pour différentes sources sonores (1958–59) began in 1957 when Hermann Scherchen asked Henri Pousseur to compose a piece for a small ensemble and tape.11 The piece was then premiered the following year on the occasion of the Congress of the Jeunesses Musicales Internationales at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, for which Iannis Xenakis designed the Philips Pavilion.

As programmatically indicated in the title, sounds from the instruments ‘rhyme’ with sounds from magnetic tape until a unified dimension of the originally heterogeneous sound material is achieved. Pousseur writes:

To “rhyme” “natural” sounds (emitted by orchestral instruments) and “artificial” sounds (played from the magnetic tape through loudspeakers), means to establish a correspondence between them, an exchange and sometimes a confusion of the origin, up to a trompe-l’oeil.12 (Pousseur quoted in Decroupet 2018: 139)

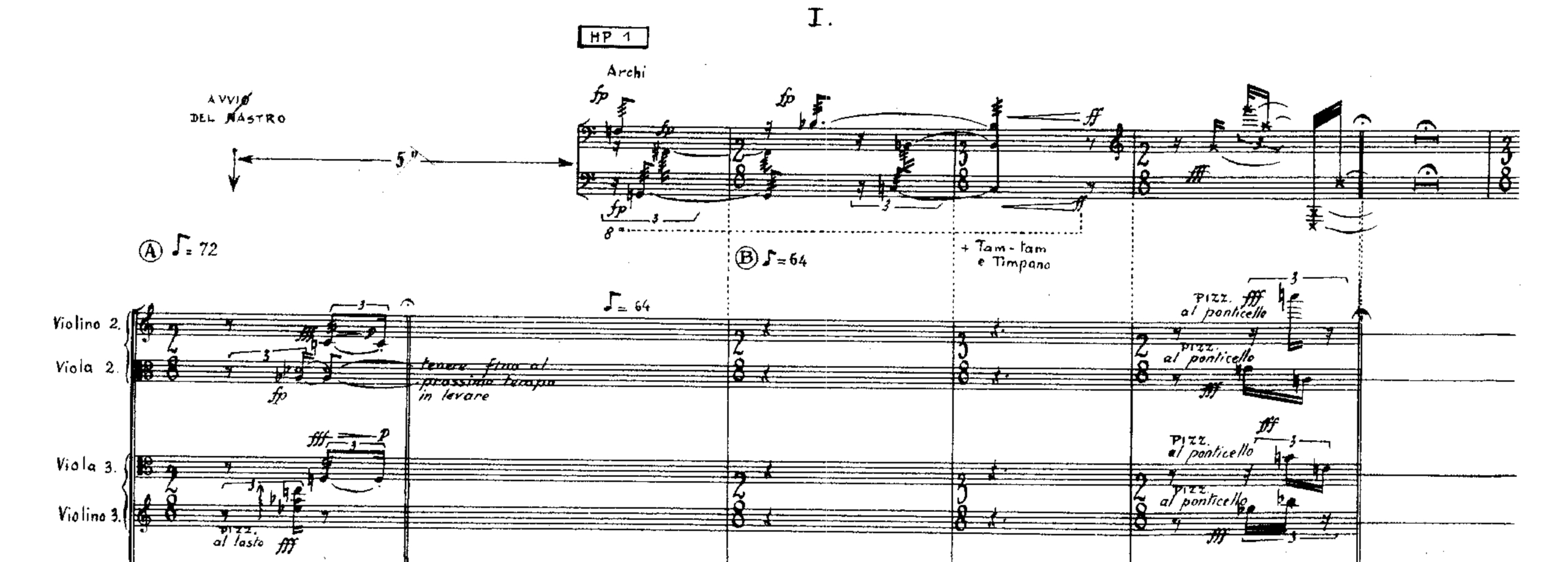

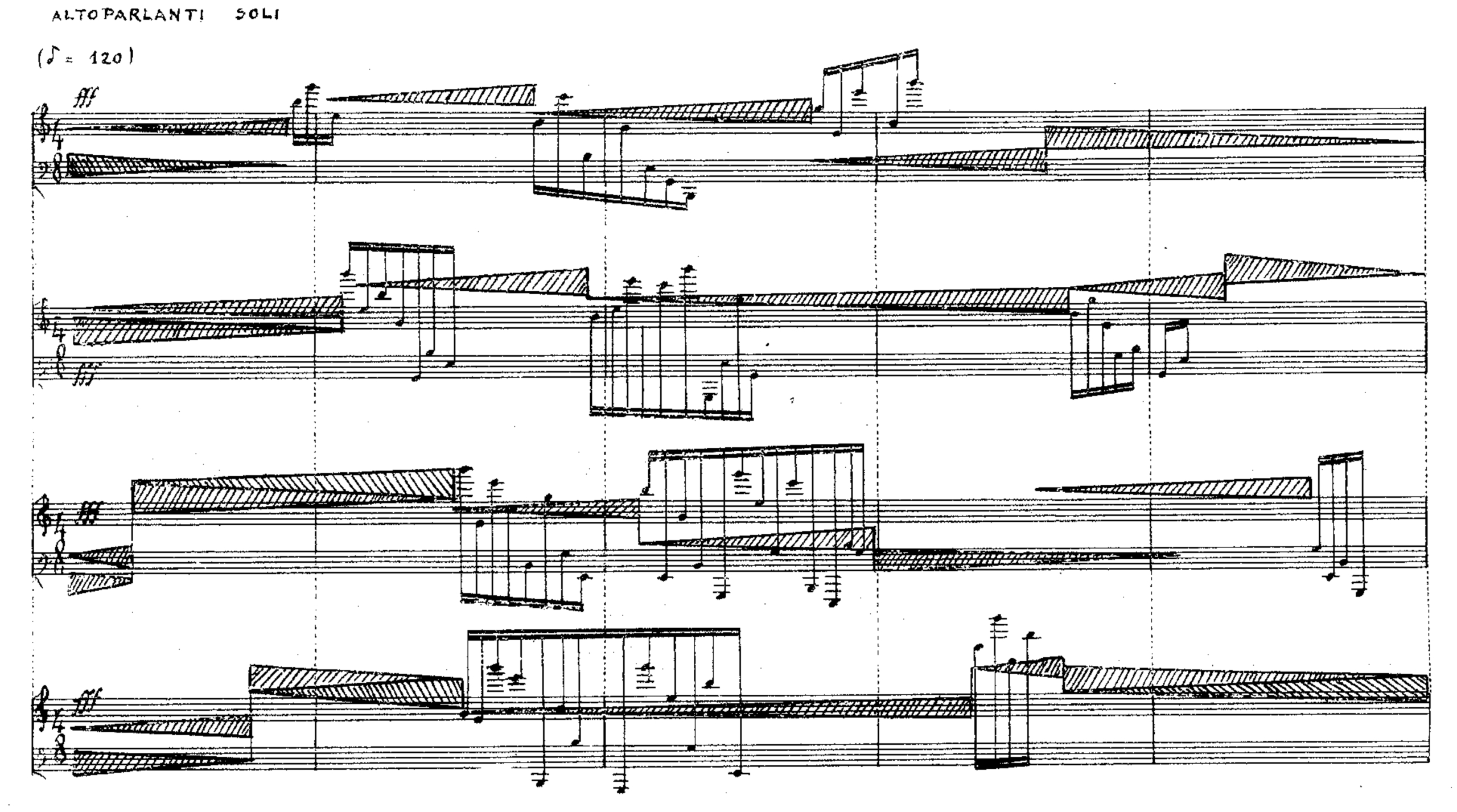

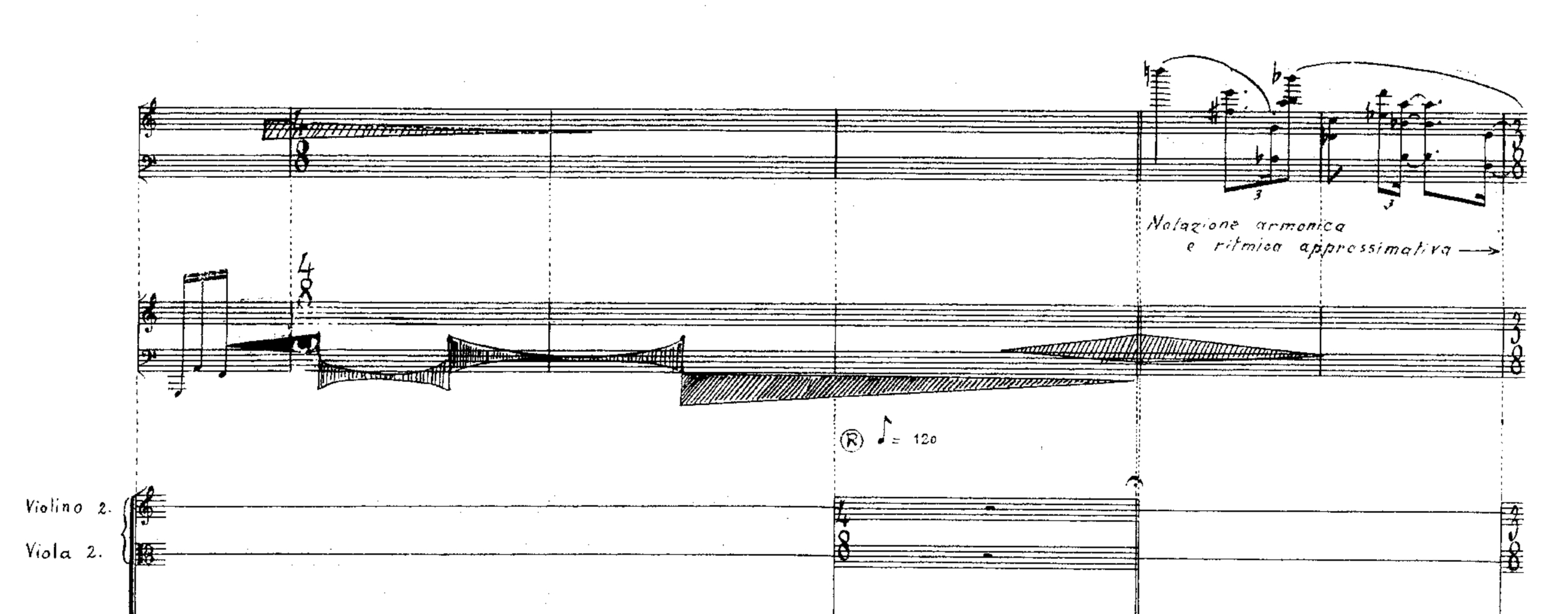

In the score published by Suvini Zerboni (see Pousseur 1962), synchronisation of ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ sounds is achieved by presenting both the instrumental parts in standard notation and sections that more or less accurately represent the events on tape on the same page. This occurs indeed through three different notational typologies. The first one is a very precise standard musical notation, which is used at the beginning when orchestral sounds are emitted, previously recorded by the same instrumentalists participating in the performance. By doing so the composer intends to introduce the recorded part imperceptibly (see Figure 4.6). It is likely that these sections do not constitute a proper ‘transcription’ of the events of the tape, but rather a re-use possibly with corrections of the parts already read by the musicians for the recording before the performance. The second type consists of the transcription of tape-only parts in which dynamic indications, amplitude envelopes and frequency fields are indicated through elongated triangles, inscribed in standard stave systems with even some pitches of the pre-recorded sounds by the performers (see Figure 4.7). And finally, the third one is “an approximate transcription of harmonies and rhythms” (ibid.: 19) in standard notation as stated in the score, which is not as precise as the first one, but is intended to give a rough guide to the events on the tape (see Figure 4.8). Pousseur then uses the flexible forms for the recorded parts in light of their features, in particular he resorts to standard notation whenever the pitches and values of the recorded sounds remain rather defined. For electronically transformed sounds, however, he makes use of elongated triangles and similar forms to provide a visual track for the musicians during the performance.

Figure 4.6: Henri Pousseur, Rimes, p. 1, section Altoparlanti soli (loudspeaker only), Sugarmusic S.p.A., Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano.

Figure 4.7: Henri Pousseur, Rimes, p. 18, detail, section Altoparlanti soli (loudspeaker only), Sugarmusic S.p.A., Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano.

Figure 4.8: Henri Pousseur, Rimes, p. 19, detail, Sugarmusic S.p.A., Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano.<

Kontakte by Stockhausen

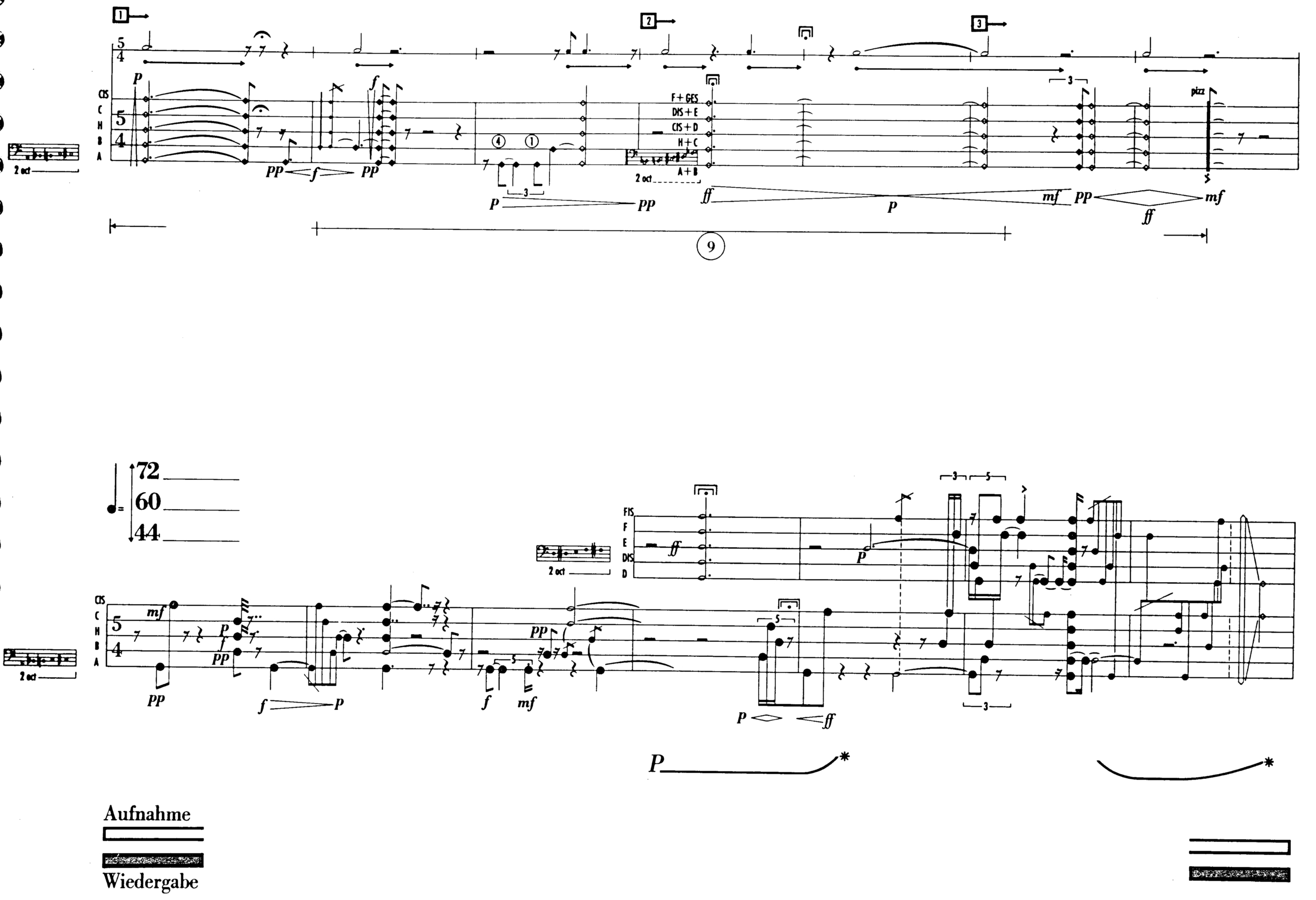

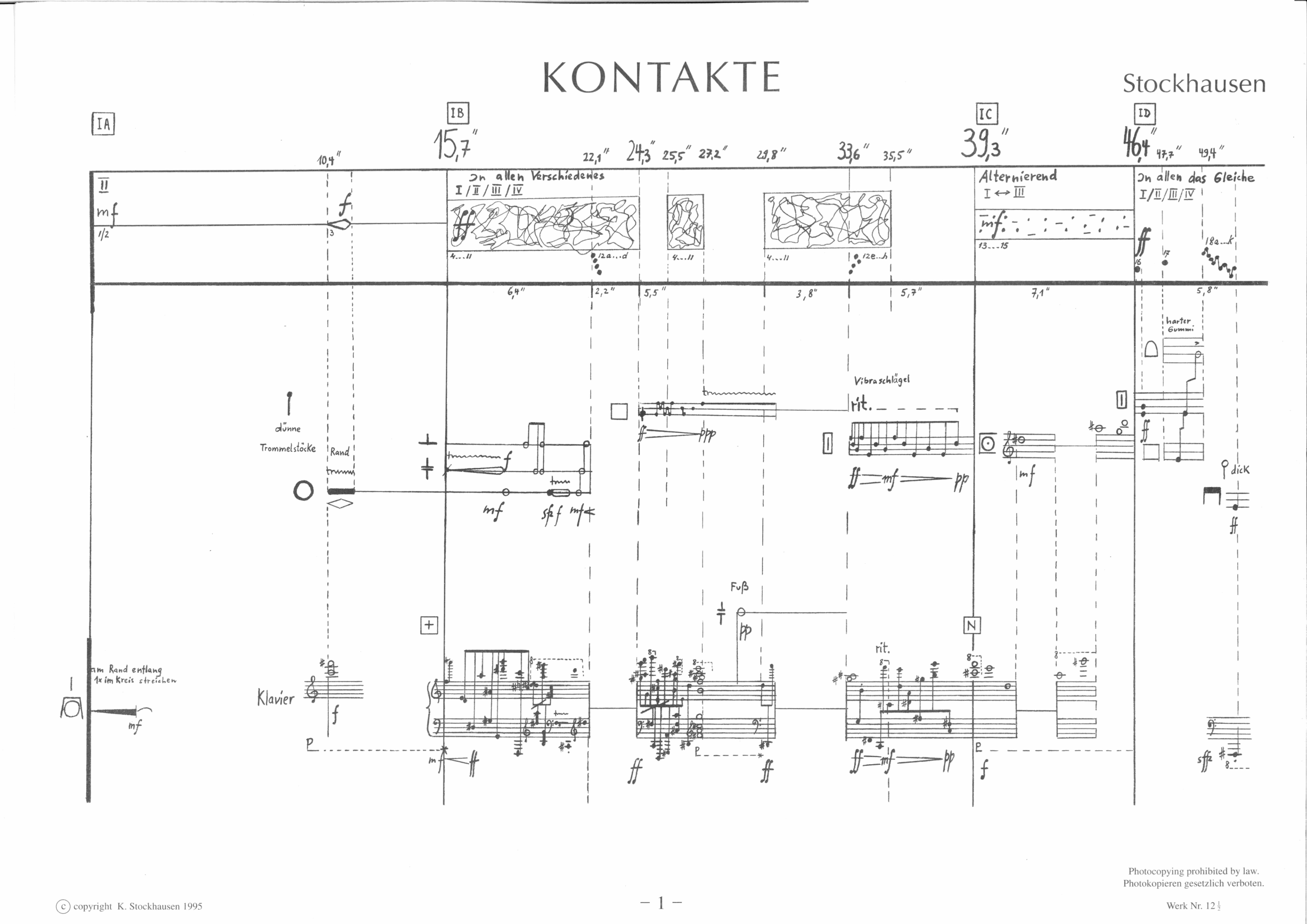

The use of writing to coordinate live and recorded events is particularly elaborated in the performance score of Stockhausen’s Kontakte Nr. 12 ½ for electronic sounds, piano and percussion, which is explicitly written for the “instrumentalists for the synchronisation of their music with the tape playback” (see Stockhausen 1995).

In October 1958, Stockhausen stated in Elektronische und instrumentale Musik that his works for electronic and instrumental music that had premiered that year focussed on “finding the superordinate laws of connection instead of using contrast as the most primitive type of form”13 (id. 1963: 151). The idea of ‘contacts’ between the two parts and also between the practices of “composing electronic music” and “writing instrumental music” (ibid.: 150) forms the basis of Kontakte.14

The work was premiered on 11 July 1960 in Cologne at the World Music Festival of the International Society for Contemporary Music. In an interview on that occasion, Stockhausen explained how he tried for the first time to merge the domains of instrumental and electronic music, thus producing an interaction between something totally fixed and something depending on the flexible performance of musicians.

In this interview, Stockhausen also gave some significant information about the function of the performance score, which can to some extent also be found in the introduction to the score:

Here [showing a page of the score, corresponding to page 33 in Stockhausen 1995], at the top of each sheet, I drew a schematic diagram of what happens in the loudspeakers, and the musicians got used to deciphering the graphic figures during the rehearsals. The time is precisely indicated. Here above, for example, they [the interpreters] have numbers of seconds […]. Here is written what the percussionist with his various instruments does and what the pianist does. Musicians must constantly listen to what comes from the loudspeaker and react to it appropriately in time and intensity.15 (id. 1960).

Stockhausen denotes the events recorded on tape in the upper system, and indicates the minutes, seconds, and tenths of a second with the help of a proportional timeline. Other numbers specify the durations of certain sections circumscribed by vertical lines, and smaller numbers refer to the duration of the tape in centimetres. Numbers in brackets indicate decibels, and roman numerals stand for the four loudspeakers, and the quadrophonic spatialisation. For example, the word ‘alternierend’ (see Figure 4.9, Section ‘IC’) means that the sounds should alternate between the indicated speakers. The composer mixes standard notation, graphical figures, and numbers, visualising the musical events on tape as precisely as possible.

Figure 4.9: Karlheinz Stockhausen, Kontakte, performance score for electronic sounds, piano and percussion, p. 1, IA – ID, Stockhausen-Verlag, Kürten, Germany.

At the end of the already quoted interview, the interviewer asks Stockhausen quite ironically who might be able to read such a score. This question may have been prompted by the fact that the performance score for Kontakte does not seem ‘traditional’. Even though the musical events on tape are measurable in seconds or centimetres (a kind of exactness), the interviewer must have imagined that this would have brought about a major interpretative change for performers accustomed to counting in beats but not necessarily in standard clock time. Such a score must have somehow required a new approach to ‘reading music’, even if the performers of the premiere of Kontakte – the pianist David Tudor and the percussionist Christoph Caskel (the same musicians of the cited performance of Kagel’s Transición II) – were already renowned performers of New Music and, as Stockhausen promptly replies, could already successfully read that score.

Writing Temporal Contact Points

Based on paradigmatic performance scores of musique mixte, I have described how some composers made the coordination and the synchronisation between live musicians and electroacoustic parts visible and traceable in the late 1950s. Two approaches emerged from this comparison: Some scores, such as those of Analogique A et B by Xenakis and of Transición II by Kagel, synchronise the two sound dimensions by means of a few essential signs like arrows and lines, i.e. with a low density of synchronisation instructions. Others, such as the scores of Rimes by Pousseur and of Kontakte by Stockhausen testify to a more intense search of the composers in finding notational strategies to effectively enable the performers to coordinate with the pre-recorded electronic sections.

Beyond the observation of these two tendencies, all musique mixte scores have one fundamental aspect in common: By nature, they have a hybrid configuration. Consequently, they give information to performers in two very different ways.

On the one hand, standard western notation allows musicians to read, understand and transform the signs into music, namely in a future musical event subsequent to the act of writing. Standard notation descending from mensural notation indicates time in a measured way: the values of the notes are specified by their form according to the time unit and defined in relation to each other.

On the other hand, visual inscriptions on a timeline offer the musicians a visual trace, often rather minimal, of a pre-existing sonic track, in which sometimes graphic signs provide cues to follow the events on tape. This type of notation can be defined as ‘chronometric’.

The performance score becomes the point of contact between two ways of writing down the fluid course of time, both however inscribed in the x-axis of the imaginary Cartesian coordinate system. In her concept of ‘flattening’ as an epistemic and aesthetic function of inscribed surfaces, Sybille Krämer reflects that a certain impulse in human beings “to transform time-bounded processes into spatial relations” may indicate that as soon as “we move in complex areas of knowledge, we privilege space and spatiality as a medium and instrument over temporality” (Krämer 2017: 244). The difference between these forms of time spatialisation, of the “flattening of time-bounded processes”, leads to a reflection on the creative processes and compositional approaches from which they derive.

Considering the four chosen works, writing of mensural time derives from a compositional process mainly undertaken with pen and paper. On the contrary, writing of chronometric time is strictly connected to the process of the studio production of tape for electroacoustic music and to the preparation of a specific performance. To use an expression by Philippe Manoury, within this genre we are faced with the encounter of “la note et le son” (Manoury 1990), of the written note and the produced sound. Musique mixte brings together two different compositional approaches, one linked to the use of writing and one linked to electronic sound production and recording. The scores of musique mixte represent intriguing examples of how writing represents a key tool for understanding complex musical configurations such as the synchronisation between different temporalities and also between different compositional approaches which increasingly overlap and influence each other.

As attempted in this essay with a focus on the synchronisation between different temporalities, a philology of electroacoustic music (of which musique mixte is only one of many configurations) should consider the coexistence of and interaction between ‘writing’ in the composer’s own workplace and ‘recording’ in the electroacoustic studio. These are two cultural techniques with which Xenakis and the other composers mentioned here were strongly confronted and whose analysis is indispensable for the understanding of their creative processes.

***

This essay is part of the research for my doctoral thesis entitled Schrift als Werkzeug. Schriftbildliche Operativität in Kompositionsprozessen früher musique mixte (1949–1959) (Minetti 2023), which was carried out within the framework of the project “Writing Music. Iconic, performative, operative, and material aspects in musical notation(s)”. I would like to gratefully thank the organisers and participants of the symposium “Xenakis 2022: Back to the Roots” (May 19–21, 2022, University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna) for their valuable comments on the topic of this paper. Translations are my own unless otherwise specified.

Endnotes

-

“Als historisch erste solcher Zeitmanipulationstechniken hat selbstredend die Schrift figuriert”. (Kittler 1993: 183).↩︎

-

Tiffon identifies three configurations of musique mixte: C+: musique mixte in the strict sense, i.e., that which combines instrumentalists with parts recorded in advance; C*: musique mixte which associates instrumentalists with electronic parts in real time, and finally, C+*: a combination of the previous two types: musique mixte in which the instrumentalists are associated with both previously recorded and live electronic parts. In the abbreviations the letter C stands for ‘concert’, the cross (+) for electronic parts recorded in advance and the asterisk (*) for electronic parts in real time. (Tiffon 2005: 23f.) The compositions by Xenakis, Pousseur and Stockhausen are ascribable to the configuration of musique mixte in the strict sense, which combines instrumentalists with parts recorded in advance. Besides live musicians, Transición II by Mauricio Kagel includes recordings made in advance and recordings made during the performance.↩︎

-

In the review by Pendleton, the work is referred to as Analogique A + B and not Analogique A et B, as it is later indicated in the published score of Analogique A (Xenakis 1968).↩︎

-

Listen to the recording of Analogique A et B from the CD Ensemble Resonanz (2005) Xenakis: Works for Strings, conducted by Johannes Kalitzke (Mode 152). Available also at this link: https://youtu.be/sOGkhekIGzo (accessed October 31, 2022).↩︎

-

“Xenakis fait partie des compositeurs qui postulent l’autonomie de l’univers de la musique électroacoustique. Aussi, il ne choisit pas la voie de nombre de compositeurs qui pratiquent de la musique mixte, notamment à partir des années 1980, dans l’idée que l’univers électronique n’est qu’une extension du monde instrumental. En ce sens, il estime – à la suite d’un Varèse – que la mixité est une affaire très délicate, qu’il convient d’utiliser avec parcimonie.” (Solomos 2017: 163).↩︎

-

As in this sketch, in the score published five years later (1968) the tape sections are indicated by Roman numerals. Section VIII at 33 seconds is, however, no longer present.↩︎

-

“In ‘Transición I’ […] war der Ausgangspunkt zur kompositorischen Arbeit die Untersuchung einiger Zusammenhänge des klanglichen Materials in Bezug auf seine zeitliche Formulierung.” (Kagel 1962: 15).↩︎

-

Kagel began to work on the electronic piece Transición I as early as 1957, but the work was only completed in 1960 at the Studio for Electronic Music of the West German Radio (WDR) (see Steigerwald 2011: 127).↩︎

-

Kagel specifies in the score: “In preparing a version for performance, a selection may be made from among the 21 sections. The number of sections so selected must make up a version of at least 10 minutes duration (the version of maximum duration will include all sections). Structures must be performed only in their entirety and are to be played once. All pages of a version must be played ‘attacca’. The arrangement of A-, B- or C-structures is free (this includes the possibility of placing structures of the same type and to end in immediate succession) subject only to the following restrictions […]” (Kagel 1963: 2).↩︎

-

In the annotation concerning the musicians of this performance, Kagel designates himself as “Tonmeister” while referring to Brown as “Toningenieur” (see also Steigerwald 2011: 127). The performance was released on Time Records in 1961 as a 33 1/3 rpm LP combined with Karlheinz Stockhausen’s compositions Zyklus and Refrain. In 2013, Naxos Classical Archives re-released it on CD, remastered by David Lennick and Joe Salerno. It is available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l3AwyNTVERQ (accessed October 7, 2022).↩︎

-

The first version was followed by two further versions, the last of which, defined by Pousseur himself as the “version régénérée” and regarded as definitive, was written in the studio of Tempo Reale in Florence and performed in Turin in 2006.↩︎

-

“Faire ‘rimer’ des sons ‘naturels’ (émis par les instruments de l’orchestre) et des sons ‘artificiels’ (émis par la bande magnétique à travers les haut-parleurs), soit établir entre eux une correspondance, un échange et parfois une confusion des caractères, pouvant aller jusqu’au trompe-l’œil.” (Pousseur, transcription of typescript dated November 29, 1961, quoted in Decroupet 2018: 139).↩︎

-

“Es geht darum, über den Kontrast hinaus – der die primitivste Art einer Form darstellt – die übergeordneten Gesetzmäßigkeiten einer Verbindung zu finden.” (Stockhausen 1963: 150).↩︎

-

Stockhausen uses the terms “composing” respectively “writing” in relation to “electronic music” and to “instrumental music” (see Stockhausen 1963: 150).↩︎

-

The interview Karlheinz Stockhausen explains “Kontakte” is available at this link: https://youtu.be/7XWNR_TcPFI (accessed October 2022). The interviewer could not yet be identified. Transcription of the original language: “Da habe ich dann jeweils auf jedem Blatt oben ein bisschen schematisch aufgezeichnet was in den Lautsprechern passiert, und die Musiker haben sich im Verlauf der Probe daran gewöhnt, das grafische Bild zu entziffern. Die Zeit ist genau angegeben. Hier oben haben sie zum Beispiel Sekundenzahlen […]. Hier ist dann jeweils geschrieben das, was der Schlagzeuger macht mit seinen verschiedenen Instrumenten und was der Pianist macht. Die Musiker müssen dauernd hören auf das, was vom Lautsprecher kommt und entsprechend zeitlich und in der Intensität darauf reagieren.”↩︎

Bibliography

Blondeau, Julia (2017) Espaces compositionnels et temps multiples : de la relation forme/matériau, Paris: Université Pierre et Marie Curie (Paris VI); https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01717249 (accessed March 27, 2024).

Celestini, Federico, Nanni, Matteo, Obert, Simon, and Urbanek, Nikolaus, eds. (2020): “Zu einer Theorie der musikalischen Schrift. Materiale, operative, ikonische und performative Aspekte musikalischer Notationen”, in Musik und Schrift: interdisziplinäre Perspektiven auf musikalische Notationen, ed. by Carolin Ratzinger, Nikolaus Urbanek, and Sophie Zehetmayer, Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink, 1–50.

Chion, Michel (1991) L’art des sons fixés ou la musique concrètement, Fontaine: Metamkine.

Cont, Arshia (2012) “Synchronisme musical et musiques mixtes: du temps écrit au temps produit”, in Circuit 22/1, 9–24; https://doi.org/10.7202/1008965ar (accessed March 27, 2024).

Decroupet, Pascal (2018) “Henri Pousseur. Three source texts concerning Rimes pour differentes sources sonores”, in The Performance Practice of Electroacoustic Music: The Studio di Fonologia years, ed. by Lucas Bennett and Germán Toro Pérez, Bern/Vienna: Peter Lang, 137–147.

Di Scipio, Agostino (2005) “Formalization and Intuition in Analogique A et B (with some remarks on the historical-mathematical sources of Xenakis)”, in Definitive Proceedings: International Symposium Iannis Xenakis, ed. by Makis Solomos, Anastasia Georgaki, and Giorgos Zervos, Athens: University of Athens: https://cicm.univ-paris8.fr/ColloqueXenakis/papers/Di%20Scipio.pdf (accessed September 10, 2023).

Harley, James (2004) Xenakis: His Life in Music, New York: Routledge.

Jordheim, Helge (2017) “Synchronizing the World: Synchronism as Historiographical Practice, Then and Now”, in History of the Present 7/1/, 59–95, https://doi.org/10.5406/historypresent.7.1.0059 (accessed March 27, 2024).

Kagel, Mauricio (1962) “Transición I: Elektronische Musik 1958–60. Bemerkungen”, in Neue Musik: kunst- und gesellschaftskritische Beiträge 5/6, [15–17].

Kittler, Friedrich (1993) Draculas Vermächtnis: Technische Schriften, Leipzig: Reclam.

Krämer, Sybille (2006) “The Cultural Techniques of Time Axis Manipulation. On Friedrich Kittler’s Conception of Media”, in Theory, Culture & Society 23/7–8, 93–109.

Krämer, Sybille (2017) “Flattening as Cultural Technique: Epistemic and Aesthetic Functions of Inscribed Surfaces”, in Journal of the American Musicological Society 70/1, 239–245.

Luque, Sergio (2009) “The Stochastic Synthesis of Iannis Xenakis”, in Leonardo Music Journal 19, 77–84, https://doi.org/10.1162/lmj.2009.19.77 (accessed September 10, 2023).

Manoury, Philippe (1990) “La note et le son : un carnet de bord”, in Musiques Électroniques: Revue Contrechamps, Essais historiques ou thématiques 11, ed. by Philippe Albèra, 151–164; https://doi.org/10.4000/books.contrechamps.1589 (accessed March 27, 2024).

Minetti, Elena (2023) Schrift als Werkzeug. Schriftbildliche Operativität in Kompositionsprozessen früher musique mixte (1949–1959), PhD thesis, mdw – University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna.

Pendelton, Edmund J. (1960) “Paris Festival of Research”, in The New York Herald Tribune. Centre Iannis Xenakis 2703, Fonds Sharon Kanach, https://www.centre-iannis-xenakis.org/items/show/242 (accessed October 31, 2022).

Sallis, Friedemann, Bertolani, Valentina, Burle, Jan, and Zattra, Laura, eds. (2018) Live Electronic Music: Composition, Performance, Study, London/New York: Routledge.

Scaldaferri, Nicola (2002) “Montage und Synchronisation: Ein neues musikalisches Denken in der Musik von Luciano Berio und Bruno Maderna”, in Handbuch der Musik im 20. Jahrhundert: 5. Elektroakustische Musik, ed. by Elena Ungeheuer, Laaber: Laaber-Verlag, 66–82.

Schwartz, Elliott (1973) Electronic Music: A Listener’s Guide, New York: Praeger.

Solomos, Makis (2017) “Notes sur la musique mixte de Xenakis”, in Analyser la musique mixte, ed. by Alain Bonardi, Bruno Bossis, Pierre Couprie, and Vincent Tiffon, Sampzon: Delatour, 163–178.

Steigerwald, Pia (2011) “An Tasten”: Studien zur Klaviermusik von Mauricio Kagel, Hofheim: Wolke.

Stockhausen, Karlheinz (1960) “Karlheinz Stockhausen explains ‘Kontakte’”, interview at the WDR Cologne: https://youtu.be/7XWNR_TcPFI (accessed October 31, 2022).

Stockhausen, Karlheinz (1963) “Elektronische und instrumentale Musik”, in Texte zur elektronischen und instrumentalen Musik, ed. by Dieter Schnebel, Cologne: DuMont, 140–151.

Tiffon, Vincent (1994) Recherches sur les musiques mixtes, Marseille: Université d’Aix-Marseille I.

Tiffon, Vincent (2005) “Les musiques mixtes : entre pérennité et obsolescence”, in Musurgia 12/3, 23–45.

Tiffon, Vincent (2013) “Musique Mixte”, in Théories dela composition musicale au XXe siècle, ed. by Nicolas Donin and Laurent Feneyrou, Lyon: Symétrie, 1297–1314.

Xenakis, Iannis (1963) “Musiques formelles: nouveaux principes formels de composition musicale”, in La revue musicale, special double issue no. 253–254, Paris: Editions Richard-Masse.

Xenakis, Iannis (1971) Musique, architecture, Tournai: Casterman.

Xenakis, Iannis (1992) Formalized Music. Thought and Mathematics in Composition, ed. by Sharon Kanach, Stuyvesant N.Y.: Pendragon Press.

Musical scores

Kagel, Mauricio (1963) Transición II für Klavier, Schlagzeug und zwei Tonbänder (1958–59) (UE 13809), London: Universal Edition.

Pousseur, Henri (1962) Rimes pour différentes sources sonores [1958–59] (S. 5520 Z.), Milano: Edizioni Suvini Zerboni.

Stockhausen, Karlheinz (1995) Kontakte für elektronische Klänge, Klavier und Schlagzeug Nr. 12 ½, Aufführungspartitur, Kürten: Stockhausen-Verlag.

Xenakis, Iannis (1968) Analogique A: Partition d’orchestre. Vol. E.A.S. 17169, Paris: Éditions Salabert.

List of Figures

Figure 4.1: Iannis Xenakis, Analogique A, orchestra score, p. 3, detail, Durand Salabert Eschig, Paris.

Figure 4.2: Iannis Xenakis, Analogique A, orchestra score, p. 5, detail, Durand Salabert Eschig, Paris.

Figure 4.3: Iannis Xenakis, Analogique A et B, sketch, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 5-5, p. 5.

Figure 4.4: Mauricio Kagel, Transición II, Structure 20 C, Universal Edition London Ltd.

Figure 4.5: Mauricio Kagel, sketch for the synchronisation of Transición II for Time Records, New York 1960, Paul Sacher Stiftung, Mauricio Kagel Collection.

Figure 4.6: Henri Pousseur, Rimes, p. 1, detail, Sugarmusic S.p.A., Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano.

Figure 4.7: Henri Pousseur, Rimes, p. 18, detail, section Altoparlanti soli (loudspeaker only), Sugarmusic S.p.A., Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano.

Figure 4.8: Henri Pousseur, Rimes, p. 19, detail, Sugarmusic S.p.A., Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano.

Figure 4.9: Karlheinz Stockhausen, Kontakte, performance score for electronic sounds, piano and percussion, p. 1, IA – ID, Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik, Kürten, Germany.