Traces of Traditional Musics in Xenakis’s Electroacoustic Œuvre

Reinhold Friedl

How to cite

How to cite

Outline

Outline

No expedition to Amazonia, Sikkim or Kilimamdjaro without a tape recorder. No tape experiments, no phonogène or electronic music in Paris, Milan or New York without Zulus, sorcerers and lamas.1 (Schaeffer 1960: 300)

Introduction

This article discusses a hitherto little-noticed aspect of Xenakis’s œuvre: the use of recordings of instruments from traditional music cultures in his electroacoustic music. “Traditional musics” shall in this article denote – according to Jaap Kunst’s definition of ethnomusicology as a subject of study – “all tribal and folk music and every kind of non-European art music” (Rice 2014: 7). This is exactly, what Xenakis was interested in: folk musics, European included, and art music from other cultures (especially Japan), or in other words: every traditional music beyond Western art music (with the exception of contemporary popular music).

Already in his youth Xenakis was interested in folk music. In his first steps as a composer, he tried to follow Béla Bartók. In the beginning of the 1950s, Xenakis started to discover non-European music and studied with Olivier Messiaen – an avowed lover of Indian Classical music. Having trained in the late 1950s with Pierre Schaeffer at the GRM (Groupe de recherches musicales) in Paris, Xenakis was – after his experience in the class of Messiaen – once more in an environment very open for traditional music from all over the world. Schaeffer had not only founded the GRM, but also Radio France’s own record label Ocora to collect and preserve traditional music heritage especially in Africa. Xenakis had a considerable private collection: The Xenakis Archives in the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris list more than 90 tapes and audio cassettes with traditional music from Zaire to Japan, from Central Africa to Bali, from Norway to Corsica. Xenakis’s first commission was to compose film music for Orient-Occident (1960), a film dedicated to the cultural connection between East and West.

Xenakis was attracted by unusual sounds: In his first tape piece Diamorphoses (1957) he used the noise of airplanes and wind, and later included in his electroacoustic music – especially in his polytopes – sounds of non-European instruments, like African thumb pianos, kalimbas or a Japanese biwa in Hibiki Hana Ma (1970). The characteristic bass bourdon of Bohor (1962) is a transposed Laotian mouth organ. Almost all of his polytopes include recordings of what he calls ‘Jew’s harps’ (‘guimbardes’). Even in his late electronic computer music, he could not resist the temptation of sound material from other continents: Thanks to the second generation of the UPIC system (Unité Polyagogique Informatique du CEMAMu) Xenakis was able to use samples, probably doing so in Voyage absolu des Unari vers Andromède (1989).

It is difficult to determine the exact provenance of the recordings of traditional musics and sounds used by Xenakis: Sometimes they are treated with tape manipulation techniques or cumulated in overlays and eventually used as samples; Xenakis hardly ever listed the sources. Recordings and production tapes as well as paper drafts from the work in the studio were often lost. But listening comparisons and Xenakis’s naming in preserved sketches and scores is unequivocal: We must revise our notion (derived largely from the rare publications on this topic mostly related to his instrumental music) that Xenakis used traditional musics only as an inspiration for structural goals. Certainly, he used large-scale recordings of traditional instruments, perhaps even parts of existing traditional music recordings. If Xenakis did some recordings himself, the question arises whether or not he ‘improvised’, thus contradicting his explicit rejection of improvisation.

The use of recordings of traditional musics in Xenakis’s electroacoustic compositions has for pragmatic reasons not been studied extensively to date: Analogue recordings in archives are hardly accessible, and if already digitised, copies are difficult to get within the normal procedure of libraries. This makes it almost impossible to compare different sources. But even if that were the case, a methodological problem arises: Musicological research is mostly based on written sources and rarely on auditive ones. In this context, re-evaluation becomes necessary, as does comparative listening.

The influence of traditional musics on Xenakis’s work has been discussed first by Makis Solomos as an example of the broader use of “musical cultures indiscriminately referred to here as traditional, local or extra-European” (Solomos 2010: 228) in contemporary music (Stockhausen, Boulez, etc.). Solomos focusses on Xenakis’s instrumental music and points out: “The integration [of non-European music] was mostly carried out for structural purposes – that is, precisely to radically renew the musical language”2 (ibid.), and not only to get an “exotic look” [optique d’exotisme]. “His interest [in non-European music] is not heard much in his work, since the reference to local music is made in a structural way”3 (ibid.: 229).

Ronan Gil de Morais calls this into question and gives a comparative listening example of an original gamelan piece from Bali that Xenakis transcribed (at least the scale) and “a conclusive section in the Claviers movement [a part of Pléïades (1978)]” (De Morais 2022: 336), as “hearing it at the BnF [Bibliothèque nationale de France], a direct correlation with the movement Claviers emerged” (ibid.). De Morais states: “Xenakis’s relationship with Indonesian gamelan music cannot be described as appropriation but rather more of an influence” (ibid.). This influence is clearly audible, thus not only structural.

For Xenakis’s electroacoustic music the influence is even stronger: Listening to his tape music – especially the single tracks of his multitrack compositions – shows that the composer extensively used recordings of traditional instruments, perhaps even some existing recordings of traditional musics. Even though this remains unclear, he was not the only one. Gianmario Borio described the long tradition of “solidarity between ethnology and avant-garde” in the 20th century (Borio 2011). And Romuald Vandelle stated as early as 1959:

If […] works of exotic music and works of experimental music are played to an unprepared audience, they might be confused. This is no coincidence but rather a result of the great similarities between the two types of music.4 (Vandelle 1959: 35)

Traditional Musics and Electroacoustic Music

Born in Brăila in Romania, Xenakis’s first attempts as a composer have been influenced by Béla Bartók, following his approach of using folk music as a source of inspiration (Baltensperger 1996; Matossian 2005). Xenakis’s family returned to Greece when he was eight years old. Xenakis remained receptive to traditional music throughout his life.

I know it sounds silly, but sometimes a sentimental melody can move me to tears. […] Music can even make me cry. It’s crazy. But it still happens today. (Xenakis 1995: 17)

For a composer who is notorious for his rational concepts and who even tried to build an automatic composing machine towards the end of his life, this is surprising. But for Xenakis, rational design and emotional content of music were not opposites.

I loved traditional music – Indian music, for example – and I always found the music of the Noh theatre to be extraordinary. Intuitively, I thought: It must be very close to the music of the first ancient tragedies. This wide-ranging interest that I have always had, comes perhaps from the fact that I was born in Romania and that very early on I heard Gypsy, Hungarian and Russian music … (Xenakis 1994: 109)

Xenakis had to flee Greece because of his opposition to the British occupation. He arrived in Paris in 1947.

I worked for Le Corbusier, first as an engineer and then as an architect, while starting to compose … folkloric-post-Bartókian music.5 (Xenakis 2003: 19)

And Xenakis opened his listening horizons to non-European music:

In 1948 I was already a composer. But I was only writing somewhat folkloristic mawkishness. Greek folklore helped me a lot. At the time this type of music sold well, thanks in particular to the Chant du Monde team, which was financed by the Soviet Union. This publisher distributed very beautiful things. And I used to go to André Schaeffner, who introduced me to the music of Bali, Java and Japan. That was in 1950.6 (Xenakis 2003: 41f.)

André Schaeffner founded the ethnomusicological department of the Musée de l’homme in Paris in 1929 and directed it until 1965. His influence on contemporary music was immense and, at least in France, well known; his correspondence with Pierre Boulez has been published (Boulez, Schaeffner 1998). Probably the same year, also in 19507 (Gerhards 1972: 366), Xenakis attended the composition class of Olivier Messiaen, who had a particularly strong interest in Indian classical music and its rhythmical structures. Xenakis discovered “Hindu music. The most civilised and perfect rhythmic organisation”, as he noted in 1951 (Mâche 2011: 21). Francois-Bernard Mâche speculates that Xenakis might even already have been involved with Indian Classical music before he met Messiaen.8 Subsequently Xenakis composed for Indian percussion instruments, as the recently discovered score of Rythmes sur Tabla (1953) shows (Declercq 2022: 338).

Since the beginning of ethnomusicology, audio recordings and the phonograph have been at the base of ethnomusicological research. Bartók especially preferred recordings of traditional music to transcriptions (Borio 2015: 136), which for him were more of an analytical tool as well as a way of providing materials for his activity as a composer. Xenakis profited early on from ethnomusicological audio recordings. He also listened to commercial records of traditional music and would have tape recorded some of them for his own personal use (De Marais 2022: 329); he might have obtained copies of unreleased recordings via Schaeffner.

I knew Noh because I discovered it at André Schaeffner’s home in the attics of the Musée de l’Homme in 1951–1952. Schaeffner was as bald as he was charming. He had a phenomenal curiosity and knowledge, and he received us in an appalling dust. I used to spend whole Sundays in his museum.9 (Xenakis 2003: 93)

Many traditional musics and most electroacoustic musics are not notated. They are hard to transcribe as the traditional European notation systems often do not apply. Thus for both, it was repeatedly disputed if they were music at all. Friedrich Blume stated in 1958 about electronic music:

[…] this fully denatured product of the montage of physical sounds has nothing to do with music […]. Here, the border is definitely crossed.10 (Blume 1959: 17)

In different contexts, neither Wendy Carlos nor Daphne Oram were allowed to call their electronic music “music”. (Holmes 2016: 86) And still, in 2006 Martha Brech writes about early musique concrète:

[…] the tonal content is not very reminiscent of music. According to today’s criteria, one should rather speak of acoustic art.11 (Brech 2006: 110)

A similar discussion took place about whether traditional musics are music, and if so, in which sense (see also Nettl 2006).

Xenakis was seduced by this common extra-musical charm. His interviews with François Delalande are entitled “You always have to be an immigrant” (Xenakis 1997). Xenakis was interested in foreign worlds and the otherness of traditional musics and musique concrète.

Xenakis was probably present at the first concert of musique concrète in 1950, at a time when he was studying with Olivier Messiaen and composing music in the spirit of Bartók. In 1953, he tried to get access to Schaeffer’s studio. Thanks to a recommendation by Messiaen, he met Schaeffer in 1954. (Solomos 2002: 2f.)

But Pierre Schaeffer did not welcome the young composer until 1957, when Xenakis got accepted to visit the ‘grand stage’, the initiation course at the GRMC, the Groupe de recherches de musique concrète at the French Radio. Subsequently he became a member of the group (Gayou 2007: 114).

Since the autumn of 1954, Pierre Schaffer had also started working for the RFOM (Radiodiffusion de la France d’outre-mer) and was less and less present at the GRMC. (Le Bail 2012: 165). Schaeffer is usually known as a pioneer of electroacoustic music and inventor of musique concrète, but his interests were much broader: Radio broadcasts in France’s African colonies were made by people in Paris who had never been to Africa. Schaeffer developed a concept for an appropriate training for future African native radio producers to run local radio stations by themselves – decolonised, so to speak (Tournet-Lammer 2008: 61). For that purpose, he set up his Studio-école and in 1956 became director of the newly founded SORAFOM (Société de radiodiffusion de la France d’outre-mer). Schaeffer war impressed by the musical richness of traditional musics from Africa and immediately founded – quite a man of action – a record label: Local music and field recordings were released, the first one in 1957 being the 10ʹʹ record Danses et chants de Bamoun with music from Cameroon. The first releases were labelled “Collection radiodiffusion outre-mer”, soon taking over the department’s name SORAFOM (which changed to OCORA (Office de coopération radiophonique) in 1960, the new name of the same radio department). Ocora still exists today as one of the most well-known ‘world music’ labels and has a back catalogue of more than 1,000 releases.12

In October 1957, Pierre Schaeffer was fired due to a political change (Tournet-Lammer: 309) and took back the direction of the GRMC the following month (Robert 2000: 43). In order to redynamise the group, he pushed pedagogical and research activities and changed the name to express a new openness: GRM, Groupe de recherches musicales.13 All kinds of music should henceforth serve as subjects of research, not only musique concrète.

Pierre Schaeffer was well aware of the already mentioned common problems of traditional musics and electroacoustic music:

One of these dead ends is ‘musical concepts’. It is now not only the scale and tonality that have come to be rejected by the most adventurous, as by the most primitive musics of our time, but the very first of these concepts: the musical note, the archetype of the musical object, the basis of all notation, an element of every structure, melodic or rhythmic. No music theory, no harmony, even atonal, can take into account a certain general type of musical objects, and in particular those used in most African or Asian musics. (Schaeffer 2017: 4)

Xenakis himself collected ‘world music’. The inventory list of the Xenakis Archive at the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris, where the family deposited Xenakis’s personal sound recordings, includes 1,139 items (analogue tapes and analogue and digital cassettes only, no vinyl records). More than 90 of those tapes contain music from a wide variety of cultures. One finds, among others, recordings of traditional musics from Senegal, Burundi, Laos, Vietnam, Java, China, Japan, Korea, but also European musics from Crete, Corsica or Norway.

Most of the tapes are not dated. The oldest is dated 1951 and contains music from Java, Sumatra, Bali, Vietnam, Tibet, Upper Volta and Gabon. The most recent dates from 1991. Some of the recordings are probably copies of commercial releases, as titles and dates coincide with releases on Ocora or other labels.

Xenakis’s Electroacoustic Compositions

It is widely known that Xenakis used instrumental recordings in his electroacoustic compositions. For his first tape composition Diamorphoses (1957) he had already recorded himself playing small bells and treated the recorded sounds in multifaceted – often systematic – ways, to create textures of different densities from single sounds.

Like most electroacoustic composers of his generation, Xenakis did not openly discuss the origin of his recorded sound sources: The production of one’s own sounds was considered a craftsman’s secret. Beatriz Ferreyra remembered using the sound of the Baschet-instruments:

Back then, we kept something like that to ourselves. We didn’t have forty thousand possibilities. When we discovered something, we kept it to ourselves so that others wouldn’t copy it. (Friedl 2018)

Xenakis for example did not list instrumental recordings in Bohor and La Légende d’Eer (1978); neither did he mention the eight minutes of what was probably a double bass solo improvisation hidden in the multitrack of La Légende d’Eer, nor contradict wrong interpretations of names in his drafts: The sound of huge thunder sheets at the end of Bohor has been denoted as ‘white noise’ and consequently taken as such in the musicological literature for years (Friedl 2019).

In this context it is important to keep in mind that statements of composers are almost always interested statements. Remembering the hard ideologic fights in Paris in Xenakis’s time between different contemporary music groups, this applies all the more. In addition, Xenakis had made a great reputation for himself as a connector of mathematics and music, a reputation he did not want to risk. Official use of improvised pre-recorded material or existing recordings might have been compromising.

Orient-Occident (1960)

In 1960, Pierre Schaeffer managed to acquire the first official commission for Xenakis. The UNESCO engaged him to compose electro-acoustic film music for Orient-Occident: images d’une exposition by Enrico Fulchignoni (Fulchignoni 1960), presented at the Cannes Film Festival the same year. The film focuses on the relationship between oriental and occidental sculpture. What could have been more obvious than to include oriental-like sounds?

The film music comprises passages that presumably stem from recordings of folk music instruments: Extensive drum passages can be found throughout the piece (ibid., e.g., 2:04–2:56 or 6:27–6:37), oriental bells and metal percussion (ibid., 5:58–6:13), overblown flute sounds (ibid., e.g., 4:10–4:25), and a bourdon similar to the one in Bohor, which is made by a Laotian mouth organ. The provenance of the sounds used is unclear, a recording has not been found in the archives so far.

These hardly hidden, probably unedited ethnomusicological borrowings are combined with sounds of other origins. For the eponymous tape piece, Xenakis shortened the music by almost 50 percent, the mentioned sounds almost completely disappeared (Xenakis 2022: CD1).

Bohor (1962)

Even though the original recording has not yet been found in the archives, hardly anyone doubts that Xenakis used the sound of a khen, a Laotian mouth organ, for the 22-minute long Bohor. Transposing it two octaves down by reducing the playback speed of a tape machine to one quarter, the khen turns into a bass drone. This drone is very prominent throughout the piece, e.g., from 13:28–15:50 (Xenakis 2022: CD1).

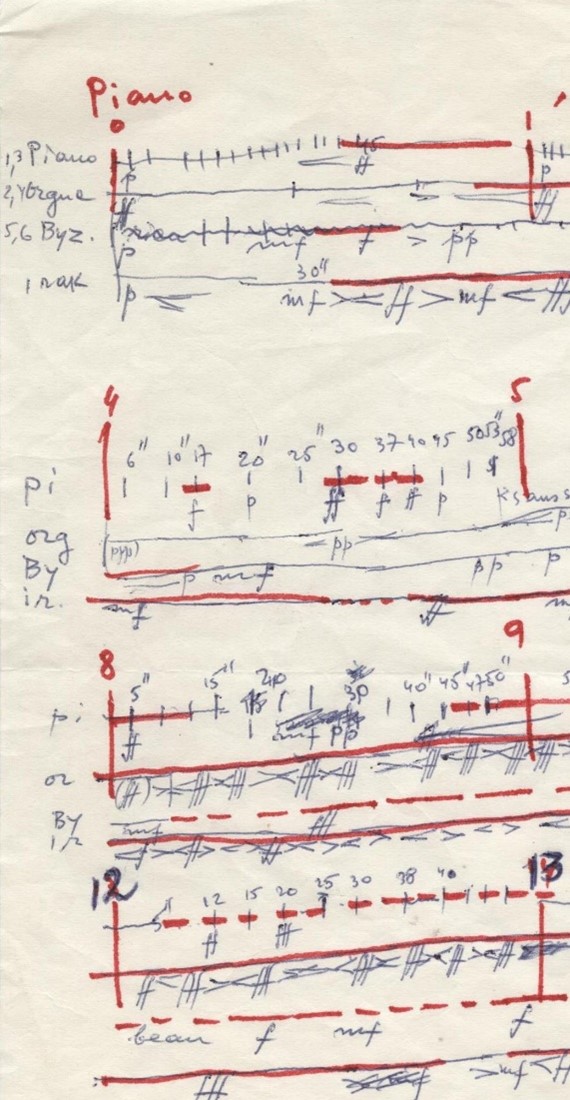

Figure 8.1: Iannis Xenakis, Bohor, score, detail with the names of the four stereo tracks, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 33-11, p. 10.

Bohor is an eight-track composition, at that time conceived for four stereo tapes, as 8-track machines were not yet available then. Xenakis named the four tracks “piano”, “orgue”, “Byz.” and “Irak”. It is interesting that Xenakis did not mention a khen. It was James Brody who wrote on the LP cover of Iannis Xenakis – Electroacoustic Music that a Laotian mouth organ had been used (Brody 1970). Since then, this has been broadly quoted and ‘orgue’ [organ] interpreted as Xenakis’s abbreviation for the Laotian Mouth Organ, in French ‘orgue à bouche’ (Figure 8.1).

Benoît Gibson tried to reconstruct the original khen recording by transposing the bourdon sound and concluded: “In Bohor, Xenakis improvises by playing the khen himself” (Gibson 2015: 87). As Xenakis hardly played any instrument, and there is no known source saying that he used to do so in studio recordings, this remains unclear. Further on, I could not find any recording of a khen on the tapes related to Bohor in the Xenakis Archives (see Friedl 2019). Given that Xenakis had a solid collection of ethnological music, it also seems possible that he used an existing recording from Laos.

On the other hand, it is interesting that Gibson assumes that Xenakis “improvised”. Not only did Xenakis reject improvisation in his music, he also made a clear distinction between improvisation and aleatoric techniques, arguing that is it not possible to delegate the latter to a performer:

The interpreter is a highly conditioned being, so that it is not possible to accept the thesis of unconditioned choice, of an interpreter acting like a roulette game. (Xenakis 1992: 38)

In this sense Gibson is correct: Xenakis improvised. This might be interesting for further discussions, as Xenakis connected “trivial improvisation” with “imprecision and irresponsibility” (ibid.: 181).

“Irak” and “Byz.” stand for jewellery and bells (“grelots”) from Iraq and Byzantium respectively which Xenakis used as sound sources. It is interesting that some authors interpreted “Byzanz” as “Byzantine chant”, but this is not mentioned in any source and no chant can be heard in the composition. Unusual sounds apparently made those authors mistakenly think of traditional music.

The Polytopes (1967–1978)

With Bohor, Xenakis explored the possibilities of multi-track composition for the first time, and he deepened his examination of this aspect in his subsequent polytopes (see Harley 1998). In the tape parts of these multimedia œuvres, Xenakis included numerous sounds of traditional music instruments:

-

1967 Polytope de Montréal (6 min) for four orchestras (pre-recorded)

-

1970 Hibiki Hana Ma (18 min) manipulated orchestra and biwa sounds, 8-track tape

-

1971 Persepolis (54 min) 8-track tape

-

1972 Polytope de Cluny (25 min) 7-track tape, automatised spatialisation

-

1978 La Légende d’Eer [Le Diatope] (45 min) 7-track tape, automatised spatialisation

Xenakis regarded this group of compositions as a kind of variation of the same work. Sounds used in earlier polytopes often reappear in the later ones.

Hibiki Hana Ma (1970)

In 1961, around the time Bohor was composed, Xenakis travelled to Japan for the first time. He met musicians such as the pianist and composer Yuji Takahashi, who was just 21 years old, as well as the composer Toru Takemitsu, through whose personal efforts he became a frequent guest in Japan. Xenakis became enthusiastic about traditional Japanese music.

We were fortunate to be able to listen to Japanese music, to visit a Noh theatre and to experience gagaku in the imperial theatre. I couldn’t understand how young Japanese composers could write tonal or serial music. […] During my conversations with Toru Takemitsu and other talented musicians, I found that most Japanese composers did not know their wonderful old-time music at all; they did not understand it and were not interested in it. They had all been trained at Western-style conservatories and despised their own tradition. (Xenakis 1995: 41)

Xenakis’s enthusiasm for Japanese music spilled over to some young Japanese musicians: Toru Takemitsu is known today for his compositional synthesis of avant-garde orchestral technique with traditional Japanese music. He also developed a preference for the biwa. In 1967 Takemitsu composed November Steps for the three-stringed instrument, shakuhachi and orchestra. Xenakis remembers:

I contributed to their rediscovery of Noh and their traditional music. I felt that their cultural revolution was leading them to reject their traditions too categorically. When I asked them to attend Noh performances, they laughed in my face.14 (Xenakis 2003: 93)

The otherness of Japanese music fascinated Xenakis deeply. In particular, the biwa caught his attention: a three-stringed instrument played with a large plectrum and which accompanies sprawling narrative chants with its noisy sound. It was probably Xenakis who made the release of biwa music on Chants du Monde possible, as he knew the label since the early 1950s (see above). His handwritten dedication was printed inside the gatefold cover of the LP:

In 1966, I had a revelation in Tokyo through the art of Kinshi Tsuruta: the Japanese troubadour singing, preserved with love for generations. It enchants you even if you don’t understand the lyrics; you can listen to this music for hours, fascinated. (Xenakis 1972)

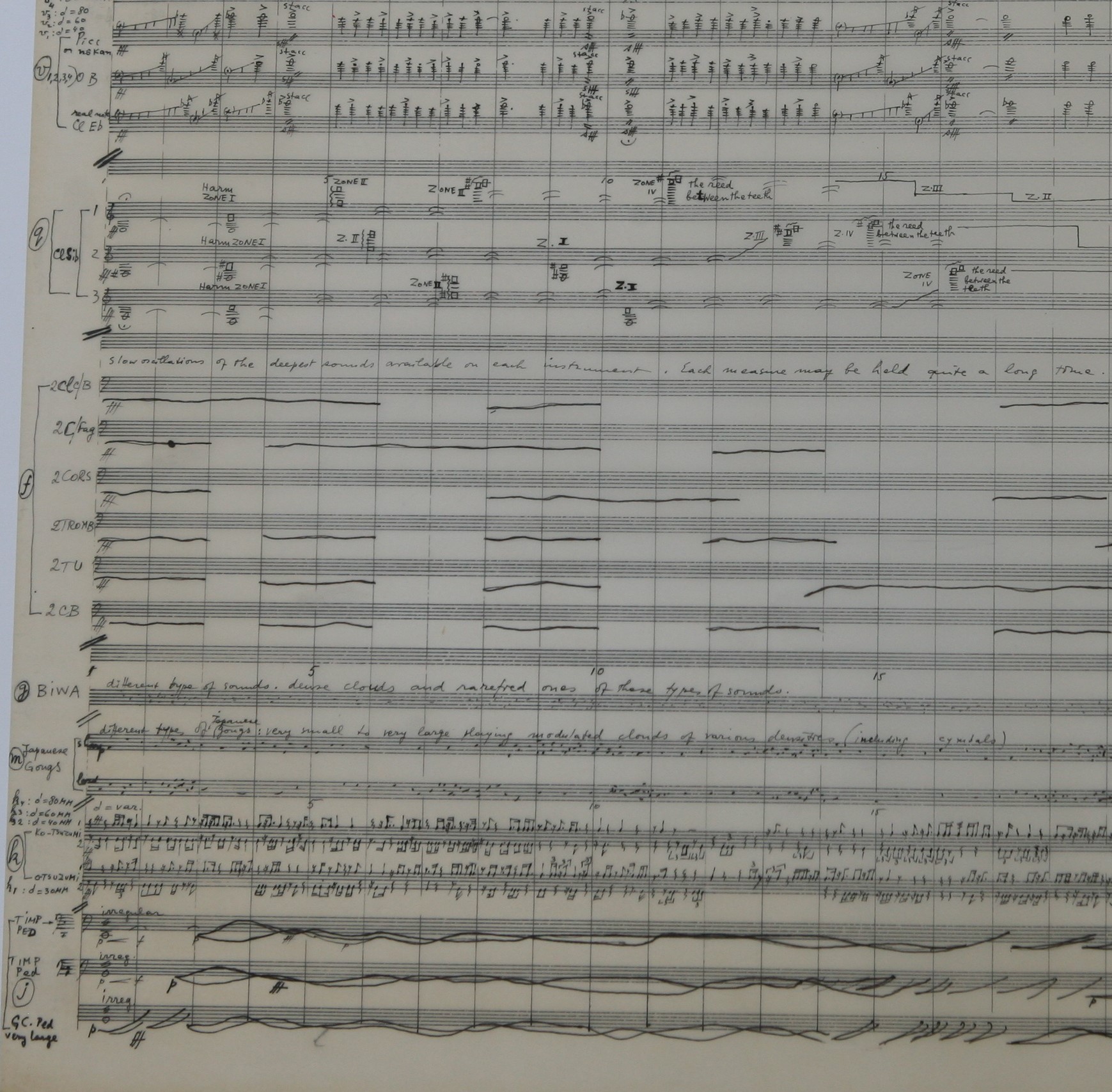

Figure 8.2: Iannis Xenakis, orchestra score to be recorded for Hibiki Hana Ma, p. 3, detail, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 12.

Xenakis wanted to include these sounds in his music. The opportunity arose in 1970 on the occasion of the World Exhibition in Osaka. In the electronic music studio of Japan’s Broadcasting Corporation NHK, Xenakis composed the 12-track tape piece Hibiki Hana Ma for the pavilion of the Japan Iron and Steel Federation. As sound material, Xenakis recorded some musical sketches (for orchestra, biwa, etc.) with the National Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra under Seiji Ozawa and with Kinshi Tsuruta, whom he held in high esteem, playing the biwa (Figure 8.2).

On the individual tracks of Hibiki Hana Ma, the biwa sounds can be clearly discerned (Xenakis 1970: track 1, 5:00–5:50), the same holds for recorded Japanese tone woods (ibid., track 8, 3:12–4:00). These ingredients amalgamate into a dense mass of sound whose individual elements, however, emerge again and again and can still be well distinguished in the stereo releases (Xenakis 2022: CD2, 2:20–10:00).

In Hibiki Hana Ma, Xenakis adapted the new fascinating sounds, but not as clearly recognisable quotations or in an eclectic sense; instead, he incorporates single notes but also treated sound by using techniques of ‘musique concrète’: recording, editing, alienating, cutting, looping, superimposing, etc.

Persepolis (1971)

Xenakis’s concept for Persepolis was more reduced. There was no special recording session anymore, but a limited list of sounds he assembled in a modular way: Each sound module appears once in each of the eight tracks, always for exactly the same length of time. As the drafts for the composition are well preserved, there is an almost full list of the sounds he superposed in a modular way, including a distorted “Japanese gong” (Collection Famille Xenakis DR: OM 27-4-3, 01). It is well perceptible in the commercial stereo versions of Persepolis as a kind of drone, similar to the transposed khen in Bohor (Xenakis 2022, CD3, e.g., after 7:32).

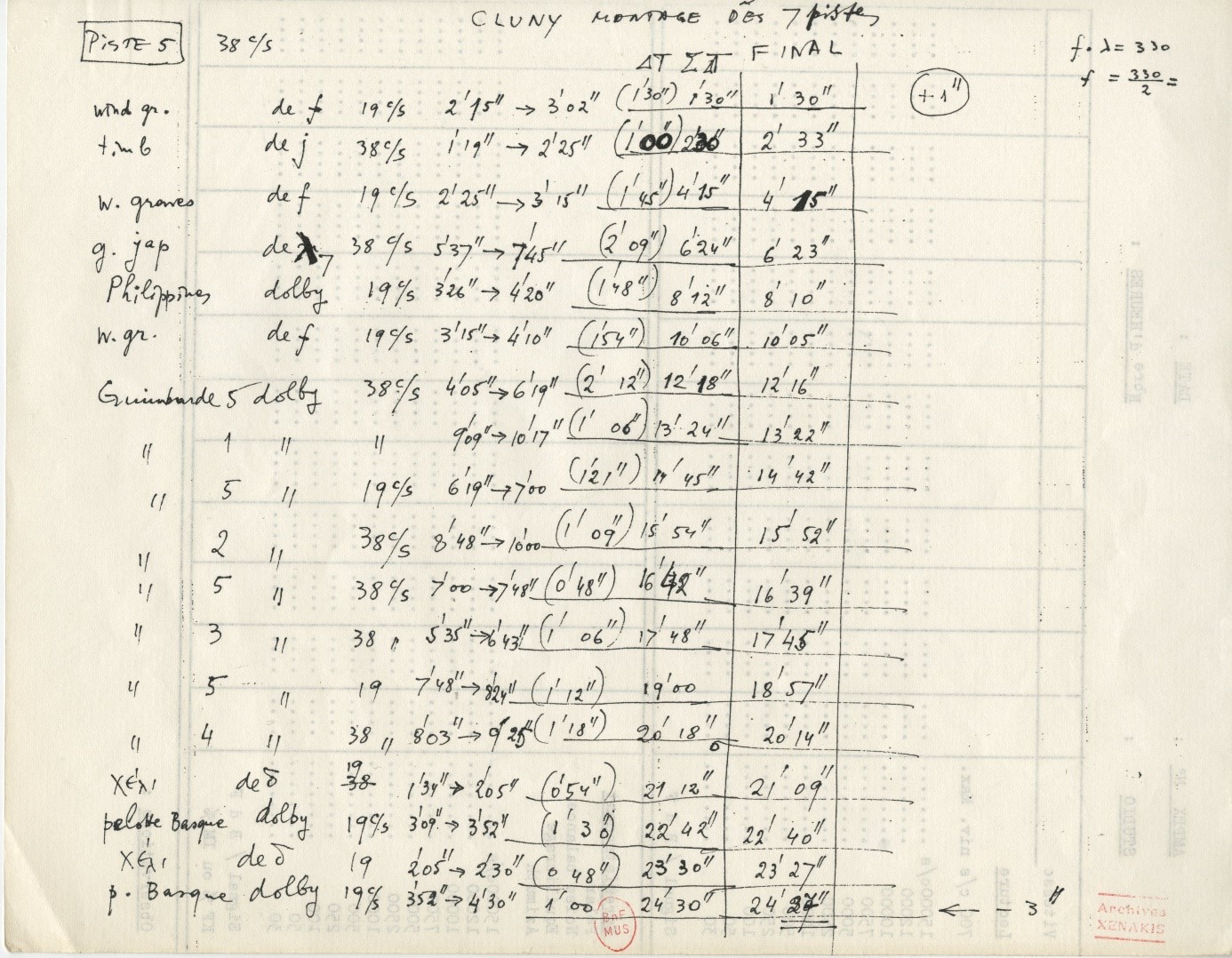

Polytope de Cluny (1972)

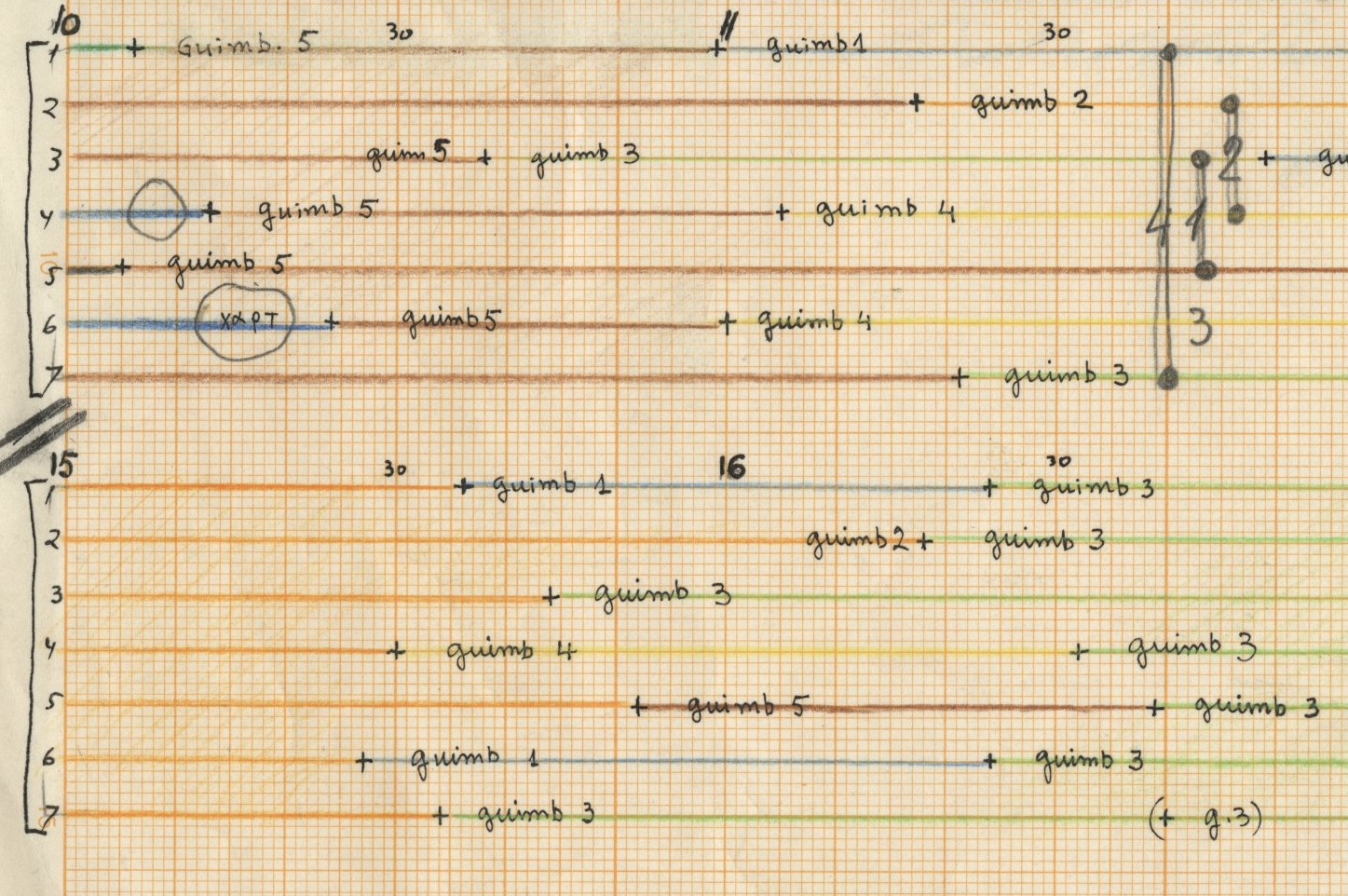

In Polytope de Cluny, Xenakis used mostly recordings of African instruments which he called “guimbardes”. The Collection Famille Xenakis DR contains extensive material including mixing plans, scores and lists of the sounds for the montage of each of the seven tracks (Figure 8.3; “Guimbarde” 1 to 5). Xenakis named five different guimbardes recordings.

Only one of them, most prominent on track 7, sounds like a – probably African – wooden Jew’s harp, as used, for example, in Namibia. The other recordings denoted as “guimbardes” do not sound like a Jew’s harp, but much more like a senza, a Central African thumb piano often also called a kalimba. The recordings seem to be made by an amateur. The instruments are played in an arhythmical way and do not show clear musical structure or virtuosity, and no great recording quality either. It is quite possible that Xenakis played on these recordings himself or used some historic recordings.

Figure 8.3: Iannis Xenakis, montage list for track 5 of Hibiki Hana Ma, names of the sounds on the left side, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 4-3, p. 7.

Where his sound material came from, who recorded it and when, apparently mattered little to Xenakis. He seemed to regard these recordings merely as raw material from which new sound material could be formed. In Polytope de Cluny, he layers seven ‘guimbardes’ recordings for several minutes (Figure 8.4) and creates a kind of an imaginary senza/Jew’s harp orchestra (Xenakis 2022: CD 2, e.g., 16:00–20:00).

This can sound very ‘electronic’, as composer Trân Quang Hai described it in respect to his tape music Vê Nguôn composed in 1975: “The Jew’s harp can produce electronic sounds. It can give me the impression of synthetic speech. I’ve used it in cartoon sound effects to imitate the robot.”15 (Quang Hai 2001: 298).

Figure 8.4: Iannis Xenakis, Montage plan for Polytope de Cluny, p. 1, detail, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 4-3.

In that period, traditional musics were pretty popular and were also used prominently in movies, as for example in the soundtracks for Federico Fellini’s Satyricon (1969) or Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Medea (1969). African sanza music had been released among others by the label Ocora, as for example Chant et sanza – Musiques traditionnelles de Burundi (1968).

Xenakis even discovered similarities between his stochastic approach and African music:

Authentic African music is not primitive. It has undoubtedly undergone a development that we know only very poorly or not at all. […] African music corresponds more to a probabilistic, stochastic approach […]. That is, it is unpredictable, while at the same time it is predictable: a kind of unpredictability in detail. (Solomos 2010)

La Légende d’Eer (1978)

The musical part of the Diatope, produced at Westdeutscher Rundfunk, shows the same concept as Polytope de Cluny: Seven tracks are fixed on an 8-track tape in order to be spatialised automatically. Xenakis reused the sounds he had already included in Polytope de Cluny, but for the first time he added his new electronic sounds created by stochastic synthesis (Friedl 2015).

Xenakis did not mind combining all these heterogeneous influences:

My music is not a revolution. My greatest achievement would be to compose music that embraces all forms of expression. However, it requires me to break free from all ties and preconditions that make me unfree. Tonal music is such a bondage, serial music, Indian music, Japanese music, and so on. They all represent worlds separate from each other, continents or islands, each with its own self-contained system of rules. The task is to find out what these islands have in common, what common structure of thought underlies them all; whether one can find access to each of them and whether the creation of a higher level of abstraction is possible. (Xenakis 1995: 52)

Xenakis’s solution was pragmatic: In his electroacoustic music, especially in the multi-channel polytopes, he simply used recorded sounds, also combining them with electronic sounds and orchestral recordings, and weaving all of this into complex sound layers. Xenakis loved the view of the foreign. It is not for nothing that the interviews Francois Delalande did with Xenakis bear the title “One must always be a migrant” (Xenakis 1997).

Xenakis even stated that he has no relation with Western music:

“My music has no roots in Western music except for the instrumentation.” (Solomos 2010)

Consequently, he also used non-western instrumentation, as in, e.g., Okho (1989) for African percussion instruments: three djembes, West African tin drums, and a “big African skin”. Xenakis attempted a kind of new synthesis: stochastically organised music on non-European instruments. The same holds for Nyuyo (1985) (nyuyo = sinking sun) for shakuhachi, a Japanese bamboo flute, and three stringed instruments: shamisen and two kotos, composed for Ensemble Yonin No Kaï from Tokyo and commissioned by the Festival d’Angers, France. We might be tempted – at least in the first part – to think it is Japanese music.

Voyage absolu des Unari vers Andromède (1989)

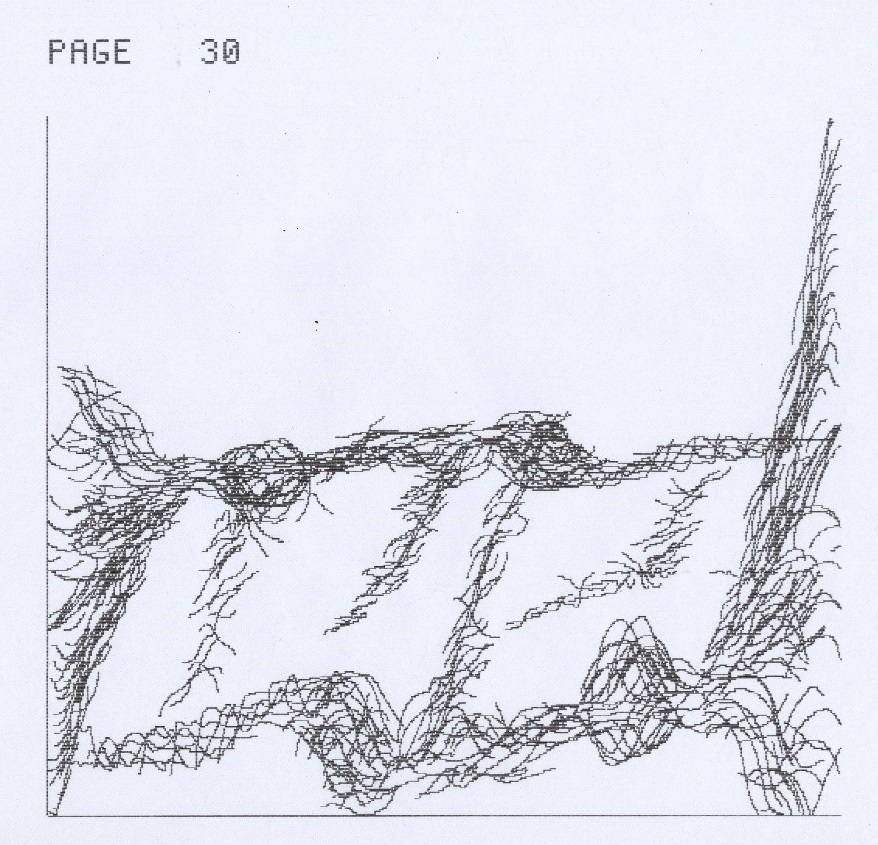

Xenakis composed Voyage absolu des Unari vers Andromède in 1989 for a Japanese kite festival with an exhibition of flying objects organised by the Goethe Institute in Osaka. To compose this piece, he used the UPIC system he had developed as a graphical interface at his research centre CEMAMu (Centre d’Études de Mathématique et Automatique Musicales) in Paris. Its interface allows electronic sounds to be drawn on a touch-sensitive screen with a special pen.

In the Xenakis Archives there is an audio cassette from 8 January 1989, labelled “Sound of Unari (Kites)” (Xenakis 1054, DONAUD 0604-999) and accompanied by a business card of “Ikuko Matsumoto, Goethe Institute Osaka”. Obviously, Xenakis had requested sound recordings of Japanese stunt kites from Japan in advance: These kites are equipped with wooden bows that start singing and humming with the airstream.

Figure 8.5 Iannis Xenakis, Voyage absolu des Unari vers Andromède, screenshot UPIC, p. 6, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 33-12.

Xenakis finished Voyage absolu des Unari vers Andromède (‘Journey of the Kites towards the Andromeda Galaxy’; see Figure 8.5) the same year, and the music sounds very similar to kite sounds.

The second generation of the UPIC system allowed it to work with recorded samples – or at least the waveform of existing samples. As Pierre Couprie assumes, Xenakis already did so in Taurhiphanie (1987), a composition for a bull arena in Southern France: “I realized that the waveforms used in UPIC probably all come from recordings of bull’s roars” (Couprie 2020: 450). If this is right, it would be obvious to assume the same for Voyage absolu des Unari vers Andromède: Xenakis might have used the kite recordings he got from Japan as waveforms for the composition. This would explain why the sounds are so similar to the real kite sounds.

Conclusion

Recording sounds on tape, manipulating the playback speed or direction, assembling new sequences is reminiscent of Xenakis’s origins in musique concrète. His sound material – especially in compositions like Polytope de Cluny – largely uses recordings of instruments of other cultures, often simply layering long passages on top of each other, even though Xenakis had great respect for the music of other cultures.

When we say ‘developed country’, we think only of washing machines, cars or the A or H bomb, but we forget that civilisations – such as those of India, for example, or Africa – are far more developed than the artistic civilisations of capitalist or socialist countries. There is no comparison between the traditional arts of India – music, dance, architecture – or those of China, Indonesia, Africa, which are the heritage of all humanity and what exists in the artistic field in Europe, the United States, or the Soviet Union. (Xenakis 1994: 129)

Xenakis puts himself in a tradition of “solidarity between ethnology and avant-garde” in the 20th century that “shows how cultural ‘appropriation’ can also occur beyond categories of domination and transgression”16 (Borio 2011: 127).

Most of Xenakis’s electroacoustic compositions comprise more or less treated recordings of instruments and further sound objects of other cultures (bells, jewels, kites, etc.). But there are a lot of open questions: Who played the instruments? Who made the recordings and where? Is it at all possible to find out the exact roots? Did he sometimes use existing commercial records or original field recordings?

This article shows that comparative listening and historical context in conjunction with meta-information of sources can provide a new point of view on an œuvre. This holds especially true for electroacoustic music, where most sources are auditive. Even knowing only some classification or the nature of existing sources can already enable us to deduce some theses. These theses allow us to go back to the sources with concrete questions and thus provide important clues for studying some aspects more precisely.

Xenakis himself rejected any association with musical sources:

I don’t want to have roots. Of course, I have some too. I too was exposed to influences, but fortunately so many that none of them could prove to be decisive. I have already mentioned them: Romanian and Greek folk music, Byzantine church singing, Western music, extra-European music. I tried to understand them, some I liked more, others less; but I let each of them approach me, none of them I claimed was not music. In this way, I gave myself the freedom to be without roots. (Xenakis 1995: 53)

Endnotes

-

“Pas d’expédition en Amazonie, au Sikkim, au Kilimamdjaro, sans magnétophone. Pas d’exploration magnétique, pas de phonogène ni de musique électronique à Paris, à Milan ou à New York sans zoulous, sans sorciers, sans lamas.” Unless otherwise stated, all translations by the author.↩︎

-

“l’intégration s’effectua le plus souvent à des fins structurelles – c’est-à-dire précisément pour renouveler radicalement le langage musical – et non pas dans une optique d’exotisme pour apporter une ‘couleur’ locale.”↩︎

-

“Cet intérêt s’entend assez peu dans son œuvre, puisque la référence aux musiques locales s’effectue d’une manière structurelle”.↩︎

-

“Si […] on fait entendre à un auditoire non prévuenu des œuvres de musique exotique et des œuvres de musique éxperimentale, il peut arriver qu’on vienne à les confondre. Ce n’est pas un effet du hasard mais parce qu’il existe de grandes ressemblances entre les deux musiques.”↩︎

-

“J’ai donc travaillé chez Le Corbusier, d’abord comme ingénieur puis comme architecte, tout en commençant à composer… une musique folklorico-post-bartókienne…”↩︎

-

“En 1948, j’étais déjà compositeur. Mais je n’écrivais que des mièvreries quelque peu folklorisantes. Le folklore grec m’aidait beaucoup. A l’époque ce type de musique marchait bien, grâce notamment à l’équipe du Chant du Monde que finançait alors l’Union Soviétique. Cet éditeur diffusait de très belles choses. Et j’allais au Trocadéro chez André Schaeffner qui m’a fait découvrir les musiques de Bali, de Java, du Japon. C’était en 1950.”↩︎

-

Concerning Xenakis visiting Messiaen’s class, the sources differ: Seurat states 1948–1949 (Xenakis 2003: 45), Matossian 1951 (Matossian 1981: 59), Mâche 1952 (Mâche 2011: 22).↩︎

-

“Le carnet n° 1 sur lequel Xenakis a noté esquisses et réflexions de septembre 1951 à décembre 1952 porte la trace, en octobre 1951, d’un intérêt pour ‘la musique hindoue’. Les remarques de Xenakis témoignent d’une admiration spontanée, probablement liée à un spectacle de ballet indien, et peut-être même antérieure à son contact avec Messiaen: Organisation la plus civilisée du rythme et la plus parfaite.” (Mâche 2011: 21)↩︎

-

“Je connaissais le Nô pour l’avoir découvert chez André Schaeffner dans les greniers du musée de l’Homme en 1951–1952. Schaeffner était aussi chauve que charmant. Il avait une curiosité, une connaissance phénoménale et nous recevait dans une poussière effroyable. Je passais dans son musée des dimanches entiers.”↩︎

-

“Mit Musik […] hat dieses volldenaturierte Produkt aus der Montage physikalischer Schälle nichts mehr zu tun. Hier ist die Grenze entschieden überschritten.”↩︎

-

“Doch der klangliche Gehalt erinnert wenig an Musik. Nach heutigen Kriterien müsste man eher von akustischer Kunst sprechen.”↩︎

-

https://www.radiofrance.com/les-editions/collections/Ocaora (accessed March 20, 2023).↩︎

-

The name was changed to GRM, Groupe de recherches musicales, in 1958 (Gayou 2007: 107).↩︎

-

“J’ai contribué à leur redécouverte du Nô et de leur musique traditionnelle. J’estimais en effet que leur révolution culturelle les conduisait à rejeter trop catégoriquement leurs traditions. Lorsque je leur ai demandé d’assister à des spectacles Nô, ils m’ont ri au nez.”↩︎

-

“La guimbarde permet de donner des sons de type électronique. Elle peut me donner l’impression d’une parole synthétique. Je l’ai ainsi utilisé dans le bruitage de dessin animé pour imiter le robot.”↩︎

-

“Die Solidarität zwischen Ethnologie und Avantgarde […] zeigt, wie kulturelle Aneignung auch jenseits der Kategorien von Herrschaft und Überschreitung stattfinden.”↩︎

Bibliography

Baltensperger, André (1996) Iannis Xenakis und die stochastische Musik. Komposition im Spannungsfeld von Architektur und Mathematik, Bern: Haupt.

Blume, Friedrich (1959) Was ist Musik? Ein Vortrag, Kassel: Bärenreiter (Musikalische Zeitfragen 5).

Borio, Gianmario (2011) “Vom Ende des Exotismus oder: der Einbruch des Anderen in die westliche Musik des 20. Jahrhunderts”, in Was bleibt? 100 Jahre Neue Musik, ed. by Andreas Meyer, Mainz: Schott, 114–134.

Borio, Gianmario (2015) “Die Darstellung des Undarstellbaren. Zum Verhältnis von Zeichen und Performanz in der Musik des 20. Jahrhunderts”, in Die Schrift des Ephemeren. Konzepte musikalischer Notationen, ed. by Matteo Nanni, Basel: Schwabe (Resonanzen 2), 129–146.

Boulez, Pierre, and Schaeffner, André (1998) Correspendance 1954–1970, Paris: Fayard.

Brech, Martha (2006) Können eiserne Brücken nicht schön sein? Über das Zusammenwachsen von Technik und Musik im 20. Jahrhundert, Hofheim: Wolke.

Brody, James (1970) Iannis Xenakis – Electroacoustic Music, liner notes on LP Cover, New York: Nonesuch Records.

Couprie, Pierre (2020) “Analytical Approaches to Taurhiphanie and Voyage absolu des unari vers Andromède by Iannis Xenakis”, in From Xenakis’s UPIC to graphic notation today, ed. by Peter Weibel, Ludger Brümmer, and Sharon Kanach, Karlsruhe/Berlin: ZKM, Hatje Cantz Verlag, 434–457.

De Morais, Ronan Gil (2022) “Xenakis’ journey to Indonesia: Influence on Jonchaies (1977) and Pléïades (1978)”, in Centenary International Symposium XENAKIS 22, ed. by Anastasia Georgaki, Makis Solomos, Areti Andreopoulou, Dimitris Exarchos, Elisavet Kiourtsoglou, and Iakovos Steinhauer, Athens: Spyridon Kostarakis, 328–337; https://xenakis2022.uoa.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Xenakis-22_Proceedings.pdf (accessed August 30, 2023).

Declercq, Zoé (2022) “The score of Rythmes sur Tabla, a ‘key document’ in the work of Iannis Xenakis?”, in Centenary International Symposium XENAKIS 22, ed. by Anastasia Georgaki, Makis Solomos, Areti Andreopoulou, Dimitris Exarchos, Elisavet Kiourtsoglou, and Iakovos Steinhauer, Athens: Spyridon Kostarakis, 338–359; https://xenakis2022.uoa.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Xenakis-22_Proceedings.pdf (accessed August 30, 2023).

Friedl, Reinhold (2015) “Towards a Critical Edition of Electroacoustic Music: Xenakis – La Légende d’Eer”, in Iannis Xenakis – La musique électroacoustique, ed. by Makis Solomos, Paris: L’Harmattan, 109–122.

Friedl, Reinhold (2018) Die Baschet-Instrumente und die GRM, Radio Feature, Westdeutscher Rundfunk, WDR3, Studio elektronische Musik, Cologne, September 29, 2018.

Friedl, Reinhold (2019) “Performance in Iannis Xenakis’s Electroacoustic Music”, in Exploring Xenakis. Performance, practice, philosophy, ed. by Alfia Nakipbekova, Wilmington: Vernon Press (Vernon series in music), 69–88.

Gayou, Évelyne (2007) Le GRM, Groupe de recherches musicales. Cinquante ans d’histoire, Paris: Fayard.

Gerhards, Hugues, ed. (1972) Iannis Xenakis, Paris: Discothèque de France.

Gibson, Benoît (2015) “À propos de Bohor (1962) de Iannis Xenakis”, in Iannis Xenakis – La musique électroacoustique, ed. by Makis Solomos, Paris: L’Harmattan, 84–96.

Harley, Maria Anna (1998) “Music of Sound and Light: Xenakis’s Polytopes”, in Leonardo 31/1, Cambridge: MIT Press, 55–65.

Holmes, Thom (2016) Electronic and experimental music. Technology, music, and culture, New York: Routledge.

Le Bail, Karine, and Kaltenecker, Martin (2012) Pierre Schaeffer. Les constructions impatientes, Paris: CNRS.

Mâche, François-Bernard (2011) “Xenakis et la musique indienne”, in Filigrane. Musique, esthétique, sciences, société 10/2, Paris: Delatour, 21–26; https://revues.mshparisnord.fr:443/filigrane/index.php?id=320 (accessed August 30, 2023).

Matossian, Nouritza (1981) Iannis Xenakis, Paris: Fayard.

Nettl, Bruno (2006) “Was ist Musik? Ethnomusikologische Perspektive”, in Musik – Zu Begriff und Konzepten: Berliner Symposion zum Andenken an Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht, ed. by Michael Beiche and Albrecht Riethmüller, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 9–18.

Oswald, John (1985) Plunderphonics, or Audio Piracy as a Compositional Prerogative, Wired Society Electro-Acoustic Conference, Toronto; http://www.bitwisemusic.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Plunderphonics-or-Audio-Piracy-as-a-Compositional-Prerogative.pdf (accessed August 30, 2023).

Quang Hai, Trân (2001) “Un dialogue occident-orient : l’exemple de Vê Nguôn (1975)”, in Du sonore au musicale – Cinquante années de recherches concrètes (1948–1998), ed. by Sylvie Dallet and Anne Veitl, Paris: L’Harmattan.

Rice, Timothy (2014) Ethnomusicology. A Very Short Introduction, New York: Oxford University Press.

Schaeffer, Pierre (1960) in “Cahiers d’études de la Radio-Télévision”, numéro 27/28. Quoted from Quang Hai, Trân (2001) “Un dialogue occident-orient: l’exemple de Vê Nguôn (1975)”, in Du sonore au musicale – Cinquante années de recherches concrètes (1948–1998), ed. by Sylvie Dallet and Anne Veitl, Paris: L’Harmattan.

Schaeffer, Pierre (2017) Treatise on Musical Objects. An Essay across Disciplines, transl. by Christine North and John Dack, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Solomos, Makis (2002) “Analysing the First Electroacoustic Music of Iannis Xenakis”, in 5th European Music Analysis Conference, Bristol; https://hal.science/hal-02055242/document (accessed August 30, 2023).

Solomos, Makis (2010) “Xenakis, du Japon à l’Afrique”, in Musique et globalisation: musicologie-ethnomusicologie, ed. by Jacques Bouët and Makis Solomos, Paris: L’Harmattan, 227–240.

Tournet-Lammer, Jocelyne (2006) Sur les traces de Pierre Schaeffer. Archives 1942–1995, Paris: Institut national de l’audiovisuel.

Vandelle, Romuald (1959) “Musique exotique et musique expérimentale”, in Expériences musicales, musiques concrète électronique exotique (La revue musicale 244), 35–37.

Xenakis, Iannis (1972) Facsimile printed on LP cover: Kinshi Tsuruta Et Katsuya Yokoyama, Japon: Biwa Et Shakuhachi, Paris: Le Chant Du Monde.

Xenakis, Iannis (1992) Formalized Music, Stuyvesant: Pendragon Press.

Xenakis, Iannis (1994) “Culture et créativité”, in Kéleütha, ed. by Iannis Xenakis and Benoît Gibson, Paris: L’Arche.

Xenakis, Iannis, and Delalande, François (1997) Il faut être constamment un immigré. Entretiens avec Xenakis, Paris/Bry-sur-Marne: Buchet/Chastel.

Xenakis, Iannis, and Serrou, Bruno (2003) Iannis Xenakis – l’homme des défis, les entretiens de Bruno Serrou, Paris: Editions Cig’art/Jobert.

Xenakis, Iannis, and Szendy, Peter (1994), “Ici et là. Entretien avec Iannis Xenakis”, in Les Cahiers de l’IRCAM 5, Paris.

Xenakis, Iannis, and Varga, Bálint András (1995): Gespräche mit Iannis Xenakis, Zürich: Atlantis.

Xenakis, Iannis, and Varga, Bálint András (1996) Conversations with Iannis Xenakis, London: Faber & Faber.

Audio and Video Sources

Fulchigoni, Enrico (1960) Orient-Occident. images d’une exposition, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7siM9_9GSiI&t=6s (accessed August 30, 2023).

Xenakis, Iannis (1970) Hibiki Hana Ma, 8-track version, Paris: Durand Salabert Eschig.

Xenakis, Iannis (2022) Iannis Xenakis – The Complete Electroacoustic Works, 5CD/5LP-Box, Berlin: Karlrecords.

List of Figures

Figure 8.1: Iannis Xenakis, Bohor, score, detail with the names of the four stereo tracks, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 33-11, p. 10.

Figure 8.2: Iannis Xenakis, orchestra score to be recorded for Hibiki Hana Ma, p. 3, detail, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 12.

Figure 8.3: Iannis Xenakis, montage list for track 5 of Hibiki Hana Ma, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 4-3, p. 7.

Figure 8.4: Iannis Xenakis, montage plan for Polytope de Cluny, p. 1, detail, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 4-3.

Figure 8.5: Iannis Xenakis, Voyage absolu des Unari vers Andromède, UPIC screenshot, p. 6, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 33-12.