Laura Zattra

How to cite

How to cite

Übersicht

Übersicht

Introduction

What can we deduce from the composers’ personal archives? What do archives tell us about the person who has collected and organised (or disorganised) them over the years, about their own creative process, about their ‘workshop’?

I have ‘used’ personal and institutional archives for 20 years for the purpose of constructing histories of authors, works, centres and collaborations, and incorporating philology, oral history, ethnography with an emphasis on sound technology and society studies. In each of my specific research projects, the individual sources served me in view of the single purpose of a project: analysing a musical work, reconstructing the creative process, reconstructing a biography or the history of an electronic music centre. In the past, I was less interested in reflecting on what a whole body of sources can reveal to us. But lately, the very organisation of these places (physical or virtual) has led me to think about what the sources can tell us about a musician’s way of approaching his or her work. In this paper I consider the very close relationship between the process of accumulating documents and the person who carries out this operation.

These thoughts arose almost by themselves from the method of study I have developed over the years, a method that combines philology, archaeology, oral history and ethnography with an emphasis on science, technology, social studies, and creative process studies. In my mixed approach, I always try to consider all available sources (paper, audio, video, computer, etc.), including non-textual sources and (written or oral) ‘memorial sources’ (sources containing stories with a memorial character or ethnographic documents). I believe that one of the most interesting recent musicological approaches is the one that reconstructs la fabrique des œuvres, the compositional ‘workshop’ of one composer. With this method, initiated in 2008, Nicolas Donin and Jacques Theureau studied the physical, technical and mental environment of some composers (Donin and Theureau 2008a). They also give an overview of the writings that deal with the terms of ‘art cabinet’, logbook, analysis or self-analysis of a creative activity in music (id. 2008b). The cognitive ergonomics of the compositional activity they propose sees the atelier-workshop as “the environment which provides [the creative process] with the conditions of possibility (material, tools, archives) and the set of technical problems, stylistic options, anticipations and memorisation of the elements of the work to come” (ibid.: 8).

Over the years, my mixed method of research enabled me to determine the interaction between agents and operations in the creative process, but also to reconstruct lost sources (Zattra 2007). Finally, on an even deeper level, it often allowed me to discover hidden figures who were indispensable to the creative process (e.g., computer music designers and sound designers).

Texts and Sources

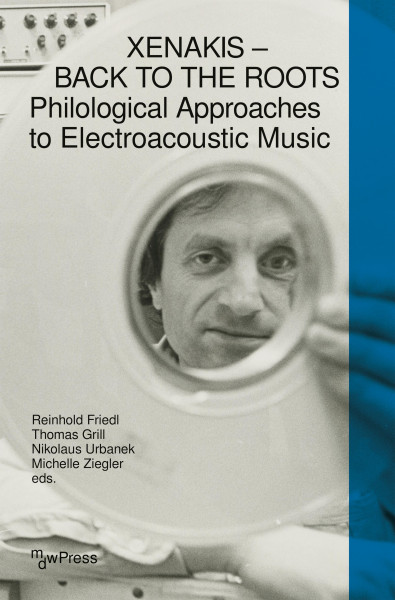

Electroacoustic music is characterised by a rich heterogeneity of sources (see Figure 2.1). Researchers who study them and deal with archives need to develop varied and specialised skills and to correspondingly establish new analytical tools. In fact, the texts (contents) and sources (media devices, instruments) may document different phases of creation, alteration, deletion, rewriting, interpretation and, due to their heterogeneity, are to be considered witnesses in the broadest sense. Sources can indeed be classified according to their form: digital, on paper or audio-video, and texts, according to their information content and the ‘code’ used to convey this information.

Such a typology cannot therefore be presented as a simple extension of, or equivalent to, the typologies specific to the study of literary texts or the art of the past. Indeed, it introduces new concepts and makes it necessary to expand the notion of ‘text’, to carefully examine the nature of information content and to take into account the multiplicity of documents that shape the production of a work. It may also be worthwhile to briefly recall the main difference between the notion of ‘source’ and that of ‘text’: A source is generally a physical testimony, a material unit, while a text is its information content (I have discussed the taxonomy of sources and texts in Zattra 2011, 2015).

Figure 2.1 exemplifies the heterogeneous nature of sources. In the case of electroacoustic and computer music, we find among them a list of digital data for synthesis; sketches of a piece (e.g., Olivier Messiaen’s sketch of Timbre-durées, a tape music piece; Battier 2010).

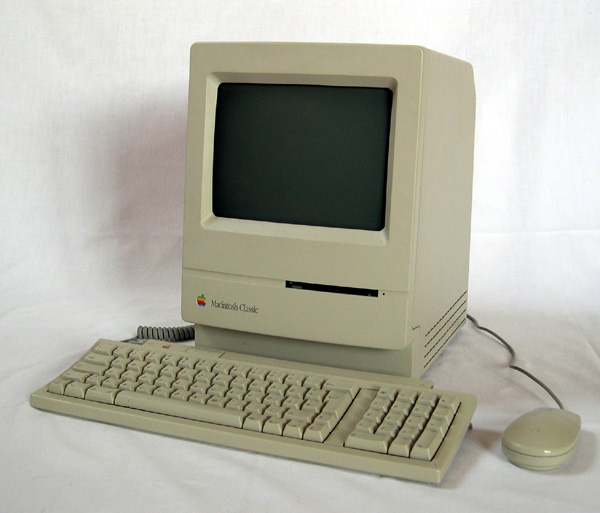

Figure 2.1: Fausto Razzi, Progetto secondo, Music5 score, p. 3, personal archive Alvise Vidolin; Spectrogram of Teresa Rampazzi, Taras su tre dimensioni, personal archive Laura Zattra; Sony tape recorder 777 owned by Teresa Rampazzi and Ennio Chiggio, personal archive Ennio Chiggio; Rui Nuno Capela, Qtractor-Screenshot, Digital audio workstation, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45607792 (accessed November 1, 2024), Public Domain; Handwritten sketch of Olivier Messiaen, Timbres-durées, (Battier 2010: 2); Laura Zattra, transcription of parts of York Höller, Résonance from the Breitkopf & Härtel score; Red box containing the audio tape of John Chowning, Stria, IRCAM archives; Macintosh Classic XO computer, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10101 (accessed November 1, 2024), Photo by Alexander Schaelss; Laura Zattra, Block diagram of Instrument 1, Wolfgang Motz, Sotto Pressione, personal archive Laura Zattra.

Moreover, there are also boxes, e.g., the red box containing the audio tape of Stria (1977) by John Chowning. Sources also include a spectrogram representation of a computer music piece, a computer itself, a tape machine, etc. Each of these sources has its unique material specificity, its own content, and requires its own ‘reading code’ to access the ‘text’.

The philological method helps to illuminate the comprehension of these texts. The technique is based on observation and the accurate description of sources related to a piece of music. They always tell something interesting about the genetic process, possible variants or versions of the music piece, etc. Philological investigations differ from musicological analyses. An analyst employs the sources in a less systematic approach, he uses them as a way to demonstrate his hypothesis and feels free to choose the more useful sources for his own purposes; he considers sources according to their content. The philologist, on the contrary, tries to consider the whole spectrum of the sources and considers both the aspects of the content and their material appearance.

If we analyse the storage medium, we can distinguish four main types of media in electroacoustic music: paper, audio, video (analogue or digital), digital (computer data, bits, codes). Paper can be used to store all sorts of written information content: composition sketches (e.g., work diagrams, notes, drafts of traditional score parts in the case of mixed music, pre-calculation materials), paper output of digital data of any kind printed for checking by the composer or compiler or to preserve a stage of creation, paper sheet music printed in conventional notation in the case of mixed music. The format designates not only the dimensions of the sheet of paper, but also the way in which it was folded or collected (e.g., punched cards were writing media at a certain era of computer music).

The audio medium has been only recently considered by traditional philology, which normally focuses on music texts existing in paper form (one of the first scholars was Angela Ida De Benedictis 2004, 2009). Many electroacoustic music pieces exist only in audio format: Analogue tapes are sources per se, as are CDs, MiniDiscs, digital audio files, etc. Unlike paper – a medium whose content seems immediately readable to us (assuming that we master that code, e.g., music notation, the alphabet, or a specific language) – audio and digital media always present the need for an intermediate ‘reading’ phase. In other words, a clear distinction should be made between the existence and the accessibility of such sources: That is to say, a document of this type does not exist if it is not reproducible and accessible. For example, accessing a digital audio source – and being able to qualify the degree of elaboration of its content – generally involves playing it and viewing it, by means of a graphical environment, in the form of a sonogram. Or, the technical ‘reading’ stage will make it possible to identify the cuts in a magnetic tape, to understand the characteristics of the different tracks, to make assumptions about the formal assembly; at a more local level, it makes it possible to advance in the knowledge of the types of sounds used (spectral properties, distinction between sounds of acoustic origin and of electronic origin, etc.).

‘Codicology’ in electroacoustic music is the study of audio media as physical objects. In fact, many problems are related to the preservation and restoration of the audio storage medium, for example, deteriorating tapes or CDs containing computer music data that are no longer readable. This discipline is very specialised and often benefits from collaboration between musicologists and sound engineers (see Orcalli 2006; Orcalli bases his theorisation on the writings of Storm 1980; Schüller 2001).

In musicology, the audio-visual medium, which was considered a fundamental source for the first time in 2008 by musicologist Bruno Bossis, is undoubtedly an exegetical document (although as a compositional strategy it was adopted well before, in audio-visual composition). With the project FIELD (FIlm on ELectroacoustics Database) Bossis studied this type of source, which he calls ‘film trace’, from 2008 on, identifying the descriptive categories and the keywords that characterise it in order to create databases (Bossis 2009a, 2009b). These documents include documentaries (sometimes unpublished), recordings of studio work sessions, recordings of rehearsals and concerts, a collection of reactions from the public, interviews, etc.

Another type of storage medium is the digital data storage device. Computers as such pose a much more dizzying series of questions than magnetic tapes, digital discs or external memories. Indeed, the computer is both an instrument and a medium. It is used for creation (composition and musical writing), for production (data management, calculations, conversions, etc.), for performance and reproduction (it reads and rereads, it calculates and recalculates, etc.) and music data storage. It can be the support of elementary or very complex contents, calculations or sound events, basic processes or high-level processes (specialised languages like Fortran, Pascal, C, just to mention a few, up to higher level programs such as Max, Pure Data, Steinberg Cubase, Csound, Audacity, Ableton Live, the infinite series of digital audio workstation software). Digital sources should include the Internet as a complex system of software, a network that connects and transforms information, an archive of primary and secondary sources (audio, video or textual) and an instrument of creation.

Finally, among the audio and audio-visual sources, interviews with the actors of the creative process are crucial. These interviews, whether produced within the framework of an ethnographic survey or in other contexts, are necessary for the reconstruction of a music whose essential ‘know-how’ is based on oral tradition (transmission of composition techniques, collaboration between the various contributors to the creative process). These oral sources are valuable for safeguarding the finer (often private) details of the creative process. The memory of the protagonists conveys knowledge that other sources cannot reveal. Compared to the material fixity of the other sources, these carry a high degree of instability. Oral documents are important for computer music research when the protagonists are still active and can therefore contribute to the knowledge of the creative process. As a result, computer music and electroacoustic music scholars often finds themselves at the crossroads of musicology and socio-ethnography (see Zattra 2021).

Archives, Persons and Personae

Archives are containers for these heterogeneous sources. Archives assemble documents of the past and the present (ongoing projects). They hold records deemed important enough to be maintained, which of course means that other materials may have been considered superfluous by their creators and thrown away. Archives can also change in nature over time: Previously they were only physical sites; now they are also virtual (online archives or computer memory). The instability of archives and the secrets they can hide in their structure have led me to consider what they can reveal to us beyond the single sources preserved in them.

This difference in storage has led me to identify two meanings of the concept of the archive (these thoughts are connected to the different nuances of meaning that Michel Foucault adopts in his theories, although my ongoing thinking touches on more practical and basic implications). In a sense, the archive can be considered a place (virtual or material) as an emanation of the artist, almost a mirror. Through their own archives, artists communicate with and talk to themselves. Hence, how they organise their materials shows how they perceive themselves and their work. Filing, rearranging, storing, etc., the present or the past, can help them understand a process, a phase, a development. It may correspond to the practice of metacognition, the self-awareness of the thought processes and the understanding of the patterns behind them.

On the other hand, the archive (virtual or material) is something that may be specifically created for others, for all those who come afterwards, who can decide to study those materials, be they musicologists or performers, etc. In that sense, the archive can be considered an entry point for us for reconstructing a history, a history of ideas and therefore, to borrow Foucault’s theory, an episteme or a ‘discursive formation’, an underlying system of thought, and the “conditions of possibility of all knowledge, whether expressed in a theory or silently invested in a practice” (Foucault 1970: 168). My attempt at theorising these concepts is based on the elementary and yet complex difference between the concepts of life and form: ‘life’ means what we are (our person, human beings), ‘form’ signifies what we seem to be (our persona, our role, our character, the aspect we present to others or what is perceived by others). Related to that is the concept of the ‘mask’. In fact, the etymology of the term ‘persona’ derives from the Latin ‘persōna’, a term probably of Etruscan origin, which meant ‘theatrical mask’.

In building an archive (this could also be the mere memory of a computer), artists externalise their persons. If they do this just for themselves, there is a close connection between person and persona. But through documents, they are also giving voice to their personas. Thus, scholars or performers who access those archives will first of all access the persona and only through this, the person as well. I will give some examples – the first two are from my experience with personal archives (the ones of Teresa Rampazzi and John Chowning), then I will describe my involvement with an institutional archive (the Studio di Fonologia di Milano now kept at the NoMus Association in Milan) and finally my experience with personal archives donated to a foundation (Camillo Togni’s and Fausto Romitelli’s collections at the Fondazione Cini in Venice).

Teresa Rampazzi

I became aware of the importance of Teresa Rossi Rampazzi (1914–2001) in 1999, when I was writing my master’s thesis (see Zattra 2020). At that time Rampazzi was 85 years old and living in a nursing home (see Zattra 2016a and my ongoing web project dedicated to Teresa Rampazzi1). The same year, Rampazzi’s children had donated their mother’s archive to the University of Padua (see Figure 2.2). Rampazzi was in a precarious state of health and had withdrawn from her music composition activity. The collection consists of approximately 50 audio tapes with her music (including final versions and production tapes), plus about 150 tapes with music she received from colleagues and friends and music she recorded from the Radio 3 Programme of the RAI, the national public broadcasting company of Italy. The physical items include letters (e.g., one from fellow composer Pietro Grossi, another one from her written to one of her students, the composer and teacher Mauro Graziani), a binder holding working notes, texts describing the pieces she wrote and a printed digital ‘score’ made using a computer program named ICMS. Today, 20 years later, these documents still have neither been inventoried nor made accessible to the public.

Figure 2.2: Collection Teresa Rampazzi, Department of Cultural Heritage, University of Padua. Photo by Laura Zattra.

It was difficult to listen to her music, as a digitisation of the tapes was only made later in 2005. It also soon became clear that this collection of the composer, pedagogue and pioneer of electronic music in Italy was incomplete. This is due to two reasons: The composer had donated her writings to friends, collaborators and relatives (books, texts, correspondences); furthermore, she was reluctant to leave written traces of her activity. As a consequence, Teresa Rampazzi’s archive is not located in a single place. For example, most of her books had been donated to the Conservatory of Music in Padua at various times from 1984 on. So, her personal library is mostly kept there.2

Some of her analogue electronic instruments (her synthesisers) can be found in the electronic music studio within the same conservatory: She left them there when she retired from teaching (in 1972, she founded one of the first electronic music courses in Italy and donated her instruments to the institution). As mentioned, other people in Italy and abroad own letters from her, tapes, books or other writings. Research had to include interviews with these people who had known and collaborated with her.

The nature of her dispersed archive reflects Rampazzi’s personality. She was forward-looking and modern (she loved, for instance, contemporary architecture and contemporary interior design). She was interested in new developments, ahead of her time and ingenious in her ability to see how music was supposed to evolve. She duly discharged everything that could remind her of the past, including letters and photographs (she didn’t like being photographed). She was interested in the future. Unfortunately, as a result Rampazzi’s last creative period in particular was forgotten, a fate she shares with other women composers who are “either ignored or thought to be marginal”, such as Delia Derbyshire or Constança Capdeville (Morgan 2017: 238; Magalhães 2022). In recent years, however, many studies (and archives) have flourished and are finally filling these voids. In the case of Teresa Rampazzi, I have developed a website (teresarampazzi.it), written several articles and analyses, participated in conferences and meetings, and established a project with the record label “Die Schachtel” (started in 2008) to salvage and release Teresa Rampazzi’s music, most of which had still been previously unpublished.

John Chowning

There are numerous sources related to Chowning’s research and music production – e.g., the famous papers about frequency modulation and spatialisation (Chowning 1971, 1973) and his many interviews and lectures – but so far, no comprehensive story of his research and production has been published nor the situation of his archives discussed. For this, I have, with François-Xavier Féron, not only led research in different archival funds but, above all, I have collected 27 hours of interviews with the composer/researcher in nine different sessions, within the framework of the RAMHO project (Musical Research and Acoustics: an Oral History) (IRCAM/Centre Pompidou 2021: 19).

Chowning’s ‘archive’ is a miscellany of different supports and contents stored in different places. His published works and his scores and computer data have been archived by himself in digital form on his computer. Since 2007, copies of the majority of these sources can also be found in the Stanford University Archives (CCRMA SAILDART Archive). These sources are mostly scans of paper printouts of digital data, and various other documents, some handwritten notes, used for research, synthesis, calculation, etc. These materials have been used to reconstruct the story of Stria, Chowning’s best-known piece (see Zattra 2007, 2016b; Baudouin 2007; Dahan 2007; Meneghini 2007). The SAILDART Archive holds a lot of historic sources concerning the CCRMA and John Chowning.3 Bruce Baumgart created the facility to provide online access to the almost one million files from the 1970s and 1980s stored in the archive of the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Lab. SAILDART includes messages written in the internal messenger service. For my particular research on Chowning, I could find documents written by him which contained programming instructions (related to compositions and software), as well as other texts including letters that he sent to colleagues around the world and simple messages between them. This turned out to be a true gold mine of information that sheds light on the everyday life of this researcher and composer, including the atmosphere in the laboratory.

However, Chowning told us that some documents and photos are still in his garage (he showed us some of them during the interviews). This part of his private archive has neither been organised nor published to date. The interviews with Chowning conducted by François-Xavier Féron and me are crucial to understanding (and presenting to readers, possibly in the future) his reactions to the heterogeneous sources we presented to him in chronological order. This research teaches us countless issues on a methodological level, including how to handle a mixture of methodologies such as history, philology, archival research and oral history.

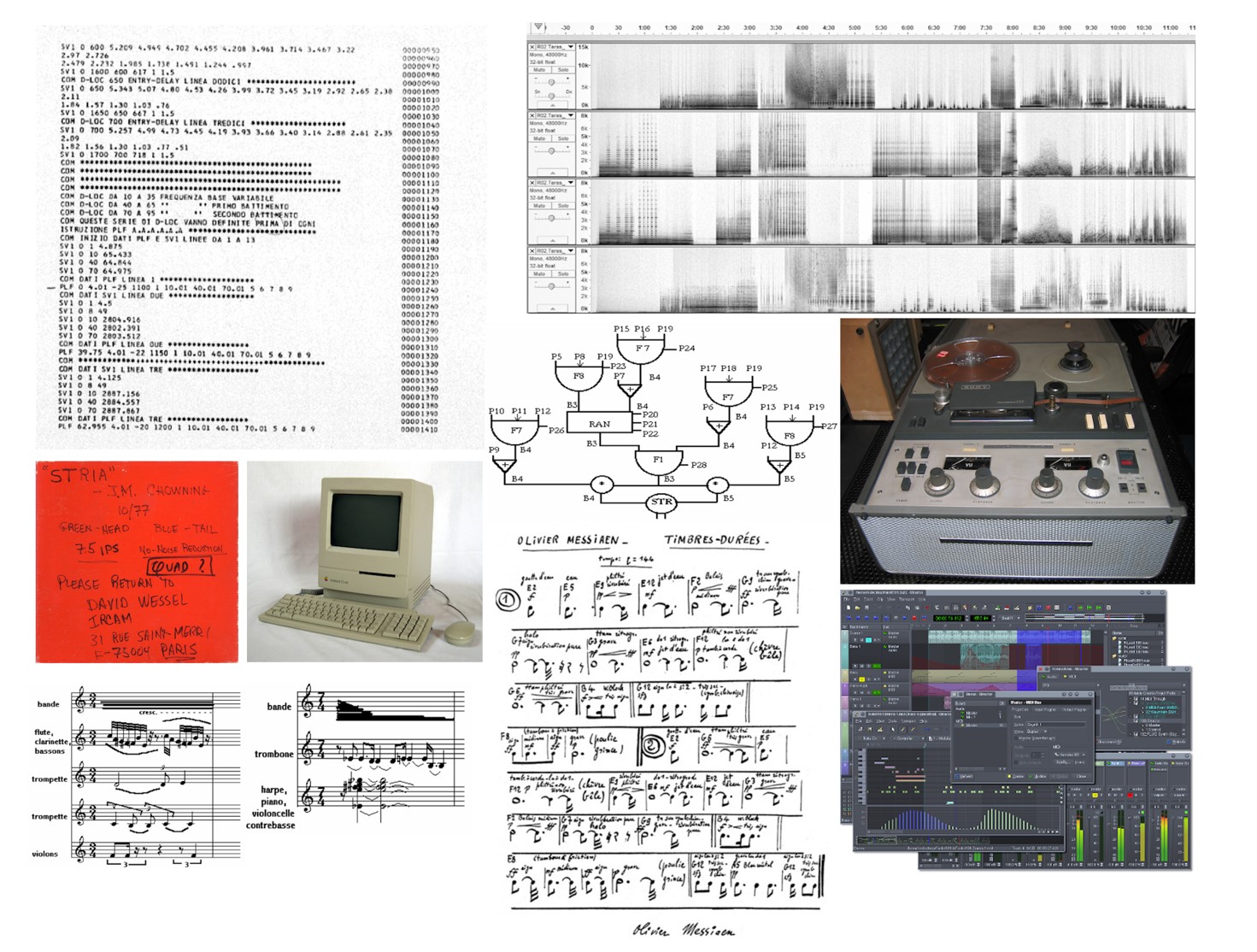

A small example demonstrates how a private source can bring forward the musicological analysis of the compositional process, the study of working conditions and workflow, and finally the analysis of the person: In May 2005, John Chowning found a meaningful handwritten document (undated, see Figure 2.3) showing a plan of Stria with more sections than the final version of the piece (e.g., T163 between T0 and T286). According to other sources, T163 would have slightly overlapped, beginning at second 163 (Zattra 2007). This Stria version has seven sections: T0, T163, T286, T466, T610, T754F, and END. Also, the F at the end of T754 occurs only here; another important detail shown here is the overall duration: 987″ =16′27″, a duration longer than both final versions.

This source from Chowing’s private archive was unpublished until 2007. In that year we decided to release it on the DVD that was part of Computer Music Journal 31:4, which was dedicated to Stria. This DVD included all sources used for the analysis and reconstruction of the piece (the sketch appears among the ‘Unpublished sources’, folder 7, John Chowning Manuscripts). Computer Music Journal 31:3 and the DVD (Computer Music Journal 31:4) constitute the first ‘critical editions’ of a computer music composition in history.

Figure 2.3: John Chowning, Stria, plan, personal archive John Chowning. Also published in Zattra 2007: 55.

The abovementioned source also helps us discover some background on the typical working conditions at the CCRMA. There is a coffee stain on the paper. Chowning told us, this might be a hint that the draft was made in an all-night working session. The plan of Stria is therefore important for many reasons: it is handwritten, therefore it shows the hand of the composer; it demonstrates an initial phase of the composition, which later evolved through the removal of some sections; and finally, it also shows some aspects relating to the composer’s lifestyle.

The NoMus Archive (Milan) and the Studio

di Fonologia Musicale di Milano della RAI

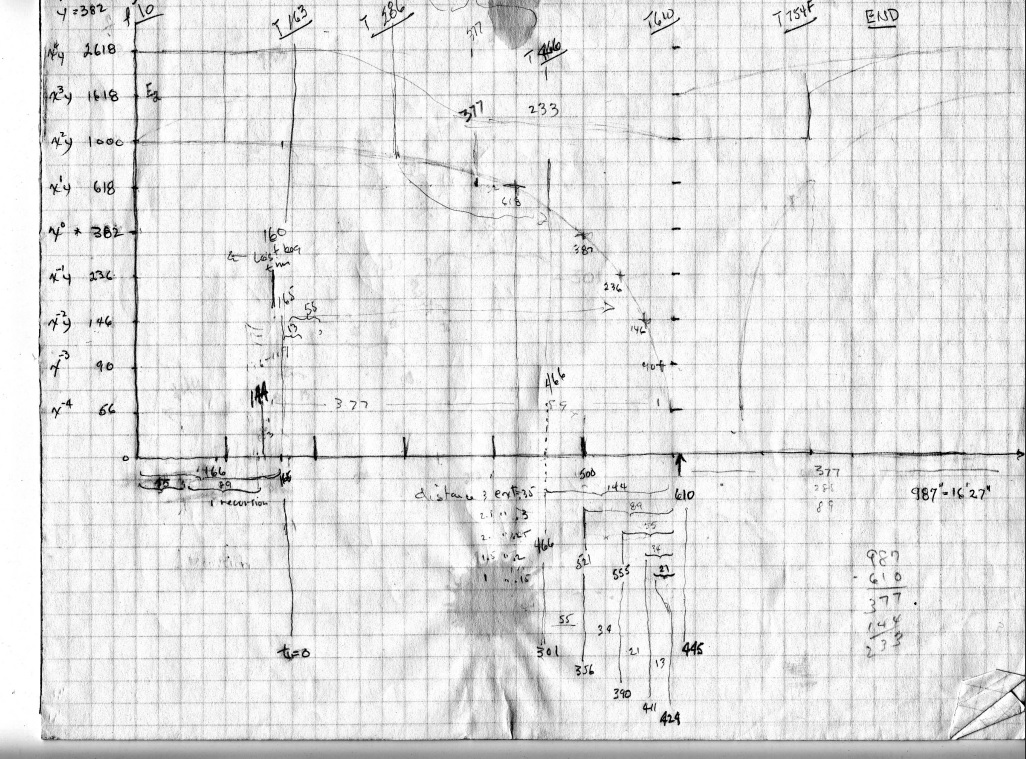

The NoMus Association in Milan was founded in 2013 on the initiative of Maria Maddalena Novati. She had worked at RAI since 1979 during the last years of activity of Marino Zuccheri, who was a technician and music assistant of the Studio di Fonologia della RAI (national public broadcasting company of Italy) in Milan (see Figure 2.4) and retired in 1983.

Figure 2.4: Studio di Fonologia at RAI in Milano, Italy, 1968. From left: Marino Zuccheri, Angelo Paccagnini, Luigi Nono, NoMus Archive, Collection Angelo Paccagnini.

Novati literally saved the instruments, tapes, correspondence and much more from the Studio di Fonologia.

One day I found all the tapes in the corridor [of the RAI]: they were being thrown away, because apparently the closet where they were stored was needed. So I rushed to the new manager to explain what was really in those boxes (excerpted from: Palma 2019, translation by the author).

The materials of the Studio di Fonologia have never been systematically archived, but correspondences, tapes and other material were indeed collected. During the 1990s, Novati archived the remaining materials (with the retirement of Zuccheri the studio was officially closed) by such criteria as nature, topic, author, and support (for a better explanation, see Novati 2001). Once she retired in 2013, Novati suggested that these materials be saved once and for all. She rented a space next to her house in Milan and founded the association for the NoMus Archive, which has since become authoritative not only for the history of the Studio di Fonologia, but also for many other topics of historical and cultural interest, including the collections dedicated to Marino Zuccheri, Alfredo Lietti (physicist and technician at the Studio), Angelo Paccagnini (director of the Studio from 1968 to 1970), Gino Marinuzzi Jr., Luigi Russolo, Francesco Balilla Pratella and Sylvano Bussotti.

Figure 2.5: Maria Maddalena Novati at the RAI studio just before her retirement (Lawendel 2009).

I visited the Studio for the first time in 2012, a few months before Novati’s retirement, in order to conduct research on Angelo Paccagnini (Zattra 2014, 2018). Figure 2.5 shows Mrs. Novati in front of her computer at RAI with the in-house catalogue of the Studio materials. I therefore had the privilege not only of seeing her work at the original site (at that time she was working on the digitisation of many reels), but also of seeing the archive moved later in 2013 from its place of origin to the warehouses of the Museum of Musical Instruments at the Castello Sforzesco in Milan, of witnessing a process of digitisation of other tapes, paper materials and the correspondence (the originals are owned by RAI and stored at the Castello Sforzesco) and therefore of seeing the copies ‘reassembled’ at the new location, at NoMus, in an organisation that represents (or mirrors) its creator, Mrs. Novati. In this case, the NoMus Archive reflects the person and persona of Novati, “discreet and indefatigable”, who understands the importance of history and preservation, “the one who saved the RAI Phonology Studio”, a person who after her retirement chose “to sell her house, buy a new one with an adjacent ‘store’ and found an association with an emblematic name, NoMus [Novecento Musica, but also Novati Musica]” (Di Marco 2016, translation by the author).

Camillo Togni

The Italian composer and pianist Camillo Togni (1922–1993) is one of the most important dodecaphonic composers in Italy, even though he is still little known abroad. He participated in the First International Dodecaphonic Congress in Milan in 1949 and attended the Ferienkurse in Darmstadt from 1951 to 1957. One of the most important works from his dodecaphonic period is Variazioni for piano and orchestra (1945–46) and major works from his total serialism phase include Rondeaux per dieci (1963–64) and a trilogy of operas (Blaubart (1972–75) and Barrabas (1981–85), the third part, Maria Magdalena, has remained unwritten). Togni composed his only tape piece, Recitativo, in March 1961 at the Studio di Fonologia della RAI in Milan. The composer stored the archival material relating to this piece in a very organised way (some of the following reflections also appear in Zattra 2021) “with a particular vocation to save any life document from decay or oblivion” (Togni 2001: 2).

The Camillo Togni Collection is kept at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini in Venice. His collection has been “ordered and rearranged following the draft of archiving arranged by the composer himself before his disappearance in 1993” (ibid.). In my research I reconstructed the creative process of Recitativo (Zattra forthcoming). The order in which he gathered the materials (sketches, notes, literature he had studied to learn electronic music technology, and materials related to the re-performance of the piece in 1991 in Brescia) shows both the daily organisation in view of those who subsequently study his music and a very ordered creative process. For instance, the choice of frequencies (mostly sinusoidal sounds) can be reconstructed thanks to a very rich handwritten source: A light brown cardboard folder labelled in black marker “Appunti per pezzo elettronico (1961)” (Notes for electronic piece) contains 137 pages with numbers and schemes. Leafing through this manuscript, we can literally see the creative process pass before our eyes page by page from the choice of pitches to the structure of the three definitive sections, including the decision not to add other sections. These ‘notes’ are compiled by Togni in this cardboard folder, closed by a push button bearing two white adhesive labels, on the front and on the spine, indicating: “CAMILLO TOGNI/RECITATIVO/PEZZO ELETTRONICO/1961”. In this cardboard folder is also a book he used to study acoustics and psychoacoustics (Righini [1960]).4 In it we find annotations in Togni’s very precise and neat handwriting with passages occasionally underlined with a ruler in graphite or blue/red pencil.

Fausto Romitelli

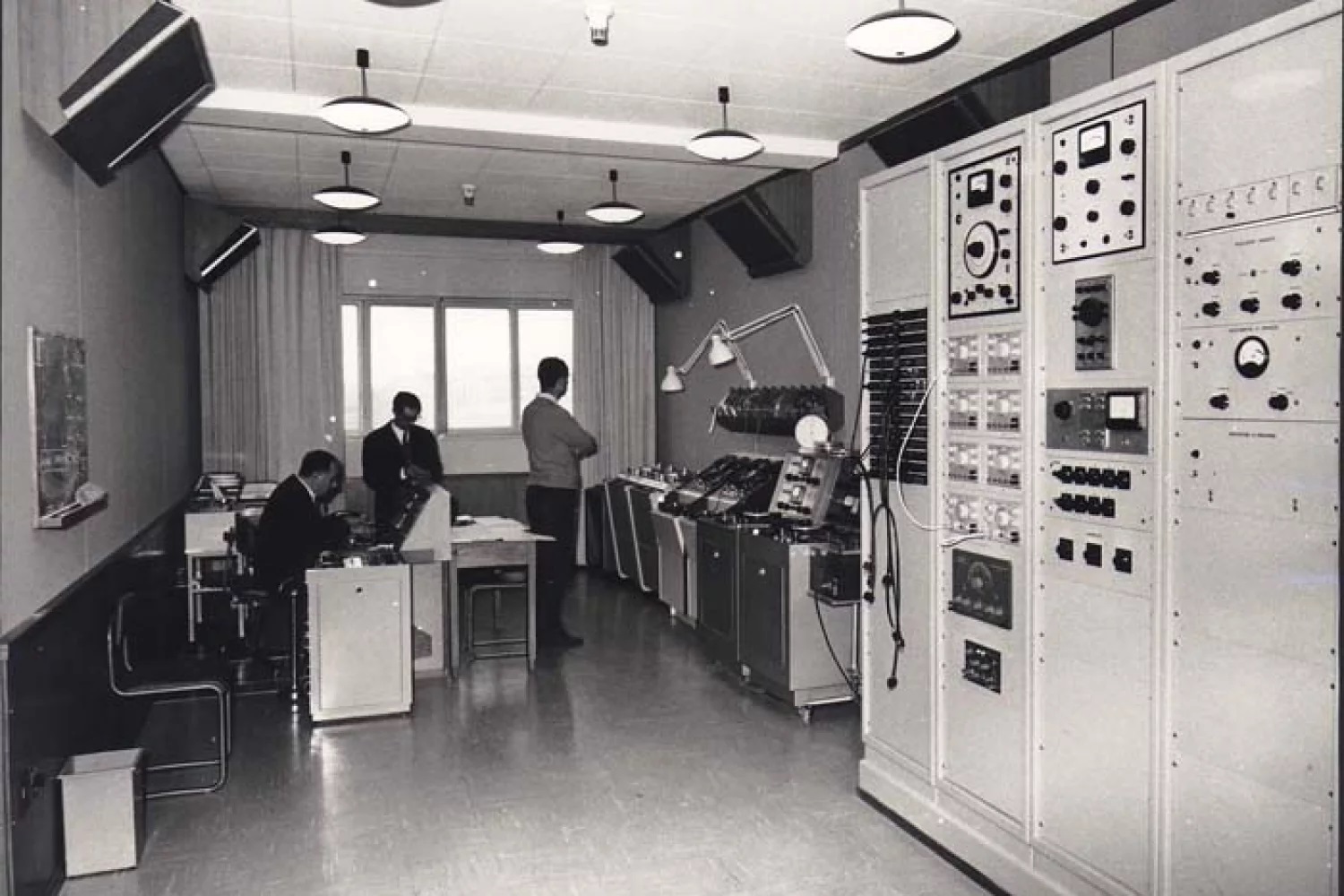

Fausto Romitelli’s (1963–2004) collection is housed at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini in Venice (Romitelli’s personal archive was donated to the Foundation by his family in 2016). Among the sources, I was able to see the complete list of computer files (patches, programmes) printed as screenshots and on paper as well as Romitelli’s computer of the 1990s. It is a Macintosh Classic personal computer designed, manufactured and sold by Apple Computer in 1991 (see Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6: Macintosh Classic, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10101 (accessed November 1, 2024). Photo by Alexander Schaelss.

It is very likely that this was the computer he bought when he began studying new technologies at the Cursus d’informatique musicale at the IRCAM (Institut de recherche et coordination acoustique/musique) in Paris and which he continued to use afterwards until his death. The computer itself is an object to study in its own right. In fact, it offers many more questions than other electroacoustic music sources, since it is both an instrument for composition and a medium.

Romitelli’s computer provides an opportunity to present some issues scholars must consider when studying computers as a source and as a text (or a series of texts), such as the dating of the machine and its files, the internal organisation of the files and what their content can tell us. These provide researchers with an inside view into the composer’s atelier. As a material object, Romitelli’s computer reveals historical/biographical details.

Musicologist Alessandro Olto carried out the first review of the materials and made paper printouts of some of the documents: The first large printout was entitled Istituto per la Musica/Fondo Fausto Romitelli – Patchwork Files + Codice Lisp by Francisco Rocca and contains Patchwork patches and Lisp codes; the second bears the title Fausto Romitelli/Documentation of new Patchwork Modules and contains Patchwork modules with a short description.5 When one consults the archives today, one only has access to the paper printouts.

Studying this documentation, I could show that Romitelli’s computer contains some standard system folders (system folder, games, RagTime Disk, Word 5.00) and a folder titled ‘Fausto3’, where he stored documents and works at irregular intervals. The same irregularity is shown by Romitelli’s paper sources in the collection, revealing the frenetic activity of a young composer. However, after a deeper analysis, this apparent haphazardness seems to correspond to his compositional strategy: He did not organise the computer documents by musical pieces or by effects, because the computer ‘tools’ he used (particularly the Patchwork patches he developed with the help of computer music designer Laurent Pottier) formed an ‘orchestra’ of instruments and effects that he built over time and used in various pieces during the 1990s.

These files are the result of Pottier’s collaboration with Romitelli. The first evident aspect is the dating of the files. The dates range from April 1993 to May 1996; only five files are dated much later, 13 July 2001.6 However, some files are dated 27 August 1956. This is obviously surprising, but it can be explained by a dating error caused by a problem with the lithium battery of the computer (when the battery fails, most Macintosh computers reset to the birth date of one of the designers, Ray Montagne).

Future comparisons between patches, modules and codes – including a reconstruction of their chronology of usage – could shed light on the evolution of Romitelli’s compositional approach. Laurent Pottier is an important witness, because he assisted Romitelli during the composition of EnTrance in 1995, a work that clearly re-uses some computer materials previously created for Natura morta (cf. Olto 2017). For example, I have asked Pottier if they used to make digital sketching, or patches, to try effects and to test different solutions.7 He confirmed that these sketches consisted of a “calculation of harmonic structures in [the software] Patchwork, but also pencil and paper sketches, spreadsheet files, patches and music sheets made with Patchwork” (these paper and pencil sketches are stored at the Cini Foundation). When discussing the re-use of the patches – which proves the building of a collaboration and an affinity that has increased over the years – Pottier also says, “We had common musical sensitivities. Exchanges had already taken place during my DEA (EHESS 1992) [bachelor’s thesis] where I had analysed his composition Natura morta con fiamme (1992)”. Some patches (e.g., ‘blood’, ‘cupio1’, ‘cupio2’ or ‘domeniche’) clearly correspond to specific pieces: Blood on the Floor, Painting 1986 (2000), Cupio Dissolvi (1996), and Domeniche alla periferia dell’impero (1996–2000), respectively. During my interview, when asked if they had “develop[ed] a specific way to communicate? New terms?”, Pottier states that they “have developed specific instruments for CAO (computer-assisted composition) in Patchwork and for synthesis (with Csound)”. Pottier’s personal archive is also important. He has digital and paper documents and copies of scanned documents. He is the founder of several projects for preserving electronic music through technical porting to current software in order to solve the serious problem of obsolescence. Among the numerous articles, papers and projects developed during his collaborations, the two projects Antony (Pottier et al. 2018) and Sidney (Lemouton et al. 2018) were developed at the IRCAM and the University VIII Saint Denis in Paris. Hence, to study Romitelli’s music, we must consider sources scattered in various places, the archives of Fondazione Cini, Laurent Pottier’s personal archive and probably also the IRCAM’s archive, not to mention different oral sources as well.

Conclusions

In this article, I have tried to demonstrate that there is a close connection between the importance of the study of sources in electroacoustic music (source criticism, philology and analysis) and the importance of considering the corpus of sources in their entirety (the archive). An archive – whether it is gathered by the artist or by an archivist – is a mirror of the collector’s personality. It is closely related to the image that person wants to convey of him- or herself (of one’s persona) and an intimate link to one’s inner identity (one’s ‘person’, in line with the etymological meaning of this term). The work of musicologists, in addition to being an archive job based on sources and source criticism, also involves ethnographic and anthropological fieldwork. Archives may be living ecosystems continually evolving for reasons such as the obsolescence of technology and tools. They need to be updated not only for re-performances of a musical piece but indeed also as the living artists continue to advance in their musical and artistic visions. More often than not, we are dealing with open archives precisely because artists continue to produce. Alongside their research work grounded on sources, musicologists therefore have an obligation to hear the direct testimony of these people.

Endnotes

-

http://www.teresarampazzi.it (accessed April 5, 2023).↩︎

-

Rampazzi’s daughter donated a few remaining books and catalogues to me a few years ago, among them the original edition of Pierre Schaeffer’s Traité des objets musicaux of 1966, with Schaeffer’s dedication to Rampazzi.↩︎

-

The list of these sources can be found here: https://www.saildart.org (accessed April 5, 2023; see also Nelson 2015).↩︎

-

The book by Pietro Righini contains 136 typewritten pages, including printouts of some sonograms on photographic paper. This volume was a cornerstone publication in Italy during the early electronic music era for those learning the new sound world. Since it was written at RAI during the same period Togni worked at the Studio di Fonologia Musicale, it is most likely that someone donated it to him so that he could learn the basics of acoustics, psychoacoustics and timbre.↩︎

-

Alessandro Olto studied Patchwork and Lisp codes for the analysis of EnTrance realised by Romitelli at the IRCAM in Paris in 1995 with the assistance of the computer music designer Laurent Pottier (Olto 2016).↩︎

-

Further research will be necessary to contextualise these last files.↩︎

-

Laurent Pottier, personal email, September 19, 2022; further quotes from this email follow. The interview with Pottier as well as other investigations on the creative process of Romitelli, Mauro Lanza/Andrea Valle and Clara Iannotta will be discussed in detail in a forthcoming article.↩︎

Bibliography

Battier, Marc (2010) “Messiaen and his collaborative musique concrète rhythmic study”, in Olivier Messiaen: The Centenary Papers, ed. by Judith Crispin, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 1–27.

Baudouin, Olivier (2007) “A Reconstruction of Stria”, in Computer Music Journal (“The Reconstruction of Stria”) 31/3, 75–81; https://doi.org/10.1162/comj.2007.31.3.75 (accessed March 27, 2024).

Bossis, Bruno (2009a) “FIELD: A Film and Video Database as a Musicology Source on Electroacoustic Music”, in Proc. of the Electroacoustic Music Studies Conference, Buenos Aires; http://www.ems-network.org/ems09/papers/bossis.pdf (accessed March 27, 2024).

Bossis, Bruno (2009b) “La Perception de l’acte artistique à travers les films sur la création électroacoustique – l’exemple de l’IRCAM”, in XII Jordans de Estética e historia del teatro marplatense y congreso internacional de estética, Fundacion Destellos, CD ROM.

Chowning, John (1971) “The Simulation of Moving Sound Sources”, in Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 19/1, 2–6; reprinted in Computer Music Journal 1/3, 48–52.

Chowning, John (1973) “The Synthesis of Complex Audio Spectra by Means of Frequency Modulation”, in Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 21/7, 526–534; reprinted in Weiiand, Frits, ed. (1975) Musical Aspects of the Electronic Medium, Report on Electronic Music, Utrecht: Institute of Sonology; reprinted in Computer Music Journal 1/2, 1977; reprinted in Roads, Curtis, and Strawn, John (1985), Foundations of Computer Music, Cambridge: MIT Press.

Dahan, Kevin (2007) “Surface Tensions: Dynamics of Stria”, in Computer Music Journal (“The Reconstruction of Stria”) 31/3, 65–74; https://doi.org/10.1162/comj.2007.31.3.65 (accessed March 27, 2024).

De Benedictis, Angela Ida (2004) “Scrittura e supporti nel Novecento: alcune riflessioni e un esempio (Ausstrahlung di Bruno Maderna)”, in La scrittura come rappresentazione del pensiero musicale, ed. by Gianmario Borio, Pisa: ETS, 237–291.

De Benedictis, Angela, and Scaldaferri, Nicola (2009) “Le nuove testualità musicali”, in La filologia musicale. Istituzioni, storia, strumenti critici, ed. by Maria Caraci Vela, vol. II, Lucca: LIM, 71–116.

Di Marco, Francesco (2016) “Maddalena Novati, una vita per la musica contemporanea”, in Cultweek, 20 January 2016; https://www.cultweek.com/maddalena-novati/ (accessed March 27, 2024).

Donin, Nicolas, and Theureau, Jacques, eds. (2008a) La fabrique des oeuvres, Circuit. Musiques Contemporaines 18/1.

Donin, Nicolas, and Thereau, Jacques (2008b) “Ateliers en mouvement: interroger la composition musicale aujourd’hui”, in La fabrique des oeuvres, Circuit. Musiques Contemporaines 18/1, 5–14.

Foucault, Michel (1970) The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, New York: Random House.

IRCAM/Centre Pompidou (2021) Rapport d’activité, https://www.ircam.fr/media/uploads/uploads/Rapports%20activite/rapport-activite-2021-ircam.pdf (accessed March 27, 2024).

Lawendel, Andrea (2009) “Studio di fonologia RAI – intervista a Maddalena Novati”, 7 October 2009; http://radiolawendel.blogspot.com/2009/10/studio-di-fonologia-rai-intervista.html (accessed March 27, 2024).

Lemouton, Serge, Bonardi, Alain, Pottier, Laurent, and Warnier, Jacques (2018) “On the Documentation of Electronic Music”, in Computer Music Journal 42/4, 41–58; https://doi.org/10.1162/COMJ_a_00486 (accessed March 27, 2024).

Magalhães, Filipa (2022) “Musicological Archaeology and Constança Capdeville”, in TDR: The Drama Review 66/3, 64–77; https://doi.org/10.1017/S1054204322000302 (accessed March 27, 2024).

Meneghini, Matteo (2007) “An Analysis of the Compositional Techniques in John Chowning’s Stria”, in Computer Music Journal (“The Reconstruction of Stria”) 31/3, 26–37; https://doi.org/10.1162/comj.2007.31.3.26 (accessed March 27, 2024).

Morgan, Francis (2017) “Pioneer Spirits: New media representations of women in electronic music history”, in Organised Sound 22/2, 238–249; https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355771817000140 (accessed March 27, 2024).

Nelson, Andrew J. (2015) The Sound of Innovation: Stanford and the Computer Music Revolution, Boston: MIT Press.

Novati, Maddalena (2001) “The Archive of the Studio di Fonologia di Milano della Rai”, in Journal of New Music Research 30/4, 395–402; https://doi.org/10.1076/jnmr.30.4.395.7495 accessed March 27, 2024).

Olto, Alessandro (2016) EnTrance. Spettralismo e composizione assistita all’elaboratore in Fausto Romitelli, PhD thesis, Università degli Studi di Udine.

Olto, Alessandro (2017) “Between Spectrum and Musical Discourse. Computer Assisted Composition and New Musical thoughts in EnTrance by Fausto Romitelli”, in Sounds, Voices and Codes from the Twentieth Century. The Critical Editing of Music at Mirage, ed. by Luca Cossettini and Angelo Orcalli, Udine: Mirage, 419–452.

Orcalli, Angelo (2006) “Orientamento ai documenti sonori”, in Ri-mediazione dei documenti sonori, ed. by Sergio Canazza and Mauro Casadei Turroni, Udine: Forum, 15–94.

Palma, Mattia L. (2019) “Le signore della musica/Maddalena Novati: Io, Berio e Stockhausen”, in CultWeek, 18 December 2019; https://www.cultweek.com/le-signore-della-musica-maddalena-novati-io-berio-e-maderna/?fbclid=IwAR2baBzsThsHHoKVqu7yDWAi7QuN_QlResufp6PyqzqoZ3elvsHJ-Qj9fx8 (accessed March 27, 2024).

Pottier, Laurent, Bonardi, Alain, Lemouton, Serge, and Warnier, Jacques (2018) “Antony: Collaborative preservation system for music with electronics. Towards a digital repository of versioned computer music software environments and the creation of a documentary database”, ECLLA; https://musinf.univ-st-etienne.fr/recherches/antony_en.html (accessed March 27, 2024).

Righini, Pietro ([1960]) Acustica Musicale, Milano: RAI editions RADIOTELEVISIONE ITALIANA.

Schüller, Dietrich (2001) “Preserving the facts for the future: Principles and practices for the transfer of analog audio documents into the digital domain”, in Journal of Audio Engineering Society 49/7–8, 618–621.

Storm, William (1980) “The establishment of international re-recording standards”, in Phonographic Bulletin, vol. 27, 5–12.

Togni, Camillo (2001) Carteggi e scritti di Camillo Togni sul Novecento Italiano, Florence: Leo Olschki.

Zattra, Laura (2007) “The Assembling of Stria by John Chowning: A Philological Investigation”, in Computer Music Journal (“The Reconstruction of Stria”) 31/3, 38–64; https://doi.org/10.1162/comj.2007.31.3.38 (accessed March 27, 2024).

Zattra, Laura (2011) Studiare la Computer Music. Definizioni, analisi, fonti, Padua: Edizioni Webster.

Zattra, Laura (2014) “Angelo Paccagnini”, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani – Vol. 80, Enciclopedia Treccani, Roma/Catanzaro: Abramo Printing & Logistics, 51–54; https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/angelo-paccagnini_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/ (accessed March 27, 2024).

Zattra, Laura (2015) “Génétiques de la computer music”, in Genèses Musicales, ed. by Nicolas Donin, Almuth Grésillon, and Jean-Louis Lebrave, Paris: Presses universitaires de Paris Sorbonne, 213–238.

Zattra, Laura (2016a) “Teresa Rampazzi”, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani – Vol. 86, Enciclopedia Treccani, Roma/Catanzaro: Abramo Printing & Logistics, 51–54; https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/teresa-rampazzi_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/ (accessed March 27, 2024).

Zattra, Laura (2016b) John Chowning – Stria (online multimedia analysis); https://brahms.ircam.fr/fr/analyses/Stria/ (accessed March 27, 2024).

Zattra, Laura (2018) “Angelo Paccagnini: Composer, Director of the Studio di Fonologia di Milano, Teacher, Actor, Conductor, Writer and Musicologist”, in Marino Zuccheri & Friends, ed. by Maria Maddalena Novati, Laura Pronestì, and Marina Vaccarini, Milan: Die Schachtel, (with CD: DS35/1), 115–123.

Zattra, Laura (2020) „Taras su tre dimensioni by Teresa Rampazzi: Documenting the Creative Process”, in: Between the Tracks: Musicians on Selected Electronic Music, ed. by Miller Puckette and Kerry L. Hagan, Cambridge, MA/London: MIT Press, 2020, 241–265.

Zattra, Laura (2021) “The Electroacoustic Music Archives at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini: A Review of the Camillo Togni, Fausto Romitelli, and Giacomo Manzoni Collections”, in Archival Notes 6, 87–99.

Zattra, Laura (forthcoming) “Recitativo for tape (1961) by Camillo Togni. Tracking the creative process for his only work of electronic music”, in a forthcoming book dedicated to Camillo Togni, ed. by Angela Carone and Christoph Neidhöfer.

Websites

https://www.saildart.org, accessed April 5, 2023 (CCRMA SAILDART Archive).

http://www.teresarampazzi.it, accessed April 5, 2023 (Teresa Rampazzi’s site, created by Laura Zattra).

List of Figures

Figure 2.1: Fausto Razzi, Progetto secondo, Music5 score, p. 3, personal archive Alvise Vidolin; Spectrogram of Teresa Rampazzi, Taras su tre dimensioni, personal archive Laura Zattra; Sony tape recorder 777 owned by Teresa Rampazzi and Ennio Chiggio, personal archive Ennio Chiggio; Rui Nuno Capela, Qtractor-Screenshot, Digital audio workstation, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45607792 (accessed November 1, 2024), Public Domain); Handwritten sketch of Olivier Messiaen, Timbres-durées, (Battier 2010: 2); Laura Zattra, transcription of parts of York Höller, Résonance from the Breitkopf & Härtel score; Red box containing the audio tape of John Chowning, Stria, IRCAM archives; Macintosh Classic XO computer, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10101 (accessed November 1, 2024). Photo by Alexander Schaelss; Laura Zattra, Block diagram of Instrument 1, Wolfgang Motz, Sotto Pressione, personal archive Laura Zattra.

Figure 2.2: Collection Teresa Rampazzi, Department of Cultural Heritage, University of Padua. Photo by Laura Zattra.

Figure 2.3: John Chowning, Stria, plan, personal archive John Chowning. Also published in Zattra 2007: 55.

Figure 2.4: Studio di Fonologia at RAI in Milano, Italy, 1968. From left: Marino Zuccheri, Angelo Paccagnini, Luigi Nono, NoMus Archive, Collection Angelo Paccagnini.

Figure 2.5: Maria Maddalena Novati at the RAI studio just before her retirement (Lawendel 2009).

Figure 2.6: Macintosh Classic, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10101 (accessed November 1, 2024), CC BY-SA 3.0. Photo by Alexander Schaelss.