Some Thoughts on Co-Creation, Cultural Democracy, and a Human Rights Approach to Music Inclusion

François Matarasso

How to cite

How to cite

Outline

Outline

Introduction

The Invention of the Fine Arts

The Definition of High Culture and Its Consequences for Cultural Policy

The Benefits of Participation in the Arts and the Problem of Social Impact

Cultural Participation as a Human Right

My Definition of Co-creation

The Traction Project

Guiding Principles of the Traction Project

From Social Impact to the Capabilities Approach

From Us & Them to We

Bibliography

Introduction

We are living through difficult, dangerous times. It is not necessary to catalogue the global events of recent years, from the pandemic to war in Ukraine, in order to show that. Much that was once taken for granted, notably the commitment of some countries to democracy, is proving to be unreliable. Each of us will have been affected by these events in different ways and to different degrees. In my case, they have contributed to a profound questioning of the work I have done over the past 40 years. I am far from having worked out what I think this means, or what conclusions could be drawn from it, so the best I can offer today is some thoughts on co-creation and human rights. This is work in progress and I ask for indulgence towards the gaps and incoherences in what follows.

The Invention of the Fine Arts

In 2019, I published a book called A Restless Art, to which I gave the somewhat cheeky subtitle How participation won and why it matters. It is an account of the history, theory, and practice of community and participatory art. (I should say that, after many years of holding stubbornly to the unfashionable concept of community art because I believe that it has a meaningful theoretical basis, I am increasingly using the term “co-creation”, first because it describes the central act more precisely, and secondly because it translates more easily into other languages; I will speak of co-creation from here onwards.) To return to A Restless Art, part of its thesis was that, over the past two decades, participatory work had moved from the disreputable margins to the centre of the art world’s preoccupations. In the book, I saw this as a generally positive development, but expressed concerns about the misuse and appropriation of co-creation. Today, I think I not only underestimated that danger, but also failed to see that even the work on the margins risked being conscripted into a moral and political framework that I reject – a way of thinking that divides society between two groups: us and them.

In order to explain this, I need to go back to what Larry Shiner calls the invention of the fine arts:

The great fracture in the older system of art […] occurred in the course of the 18th century, finally severing fine art from craft, artist from artisan, the aesthetic from the instrumental and establishing such institutions as the art museum, the secular concert, and copyright. (Shiner 2003, 9)

As soon as you invent the concept of the “fine arts”, you automatically, inexorably, invent the concept of the “not-fine arts” or, to use some of the more familiar terms that are applied to this sub-category, folk art, craft, traditional art, popular art, entertainment, world music – the list could go on, but the only thing these labels have in common is the attempt to separate in a fundamental way the culture they point to from the unquestionably dominant form designated as fine art. What the Enlightenment gave us, in effect, is a two-class system for the arts, and we have lived with that since the 19th century. In fact, what was then called fine art is actually so socially, culturally, and politically powerful that it gets away with just calling itself art – or music – while the rest gets labelled pop, or rap, or muzak or whatever it may be.

The Definition of High Culture and Its Consequences for Cultural Policy

The Enlightenment’s idea of fine art was simply the cultural tastes of European elites at the time – oil painting, architecture, court music, poetry, ballet, and so on. These art forms share one key characteristic: uselessness. For that reason, a Meissen figure is fine art, while a ceramic jug or plate is not because, whatever cultural values it may be thought to embody, however skilfully it has been produced, it is tableware and serves a purpose. Why this distinction? Because only the wealthy can afford to own what is useless. Other people make art as part of living – like the songs people invent to enliven their daily labour in the field or at home, the stories shared on long winter nights, or the beauty invested in household objects. The fine arts are a deliberate expression of privilege – what Pierre Bourdieu would define as cultural capital 200 years later – and it is bad for all forms of cultural expression, as the American writer, Wendell Berry, recognises: “This definition of culture as ‘high culture’ actually debases it, as it debases also the presumably low culture that is excluded.” (Berry 2019, 564) This has had negative consequences for cultural policy in Europe since the 19th century – understanding, of course, that cultural policy exists whether or not it is expressed or formalised in government publications. Cultural policy is simply the way in which things are organised. There are two contrasting forms of cultural policy in Europe. The first is top-down. Once you believe in the fine arts, it is a small step to believing that we should generously pass on the great merit of high art to less fortunate people. In the 19th century, that largely took the form of philanthropy. Many of our great cultural institutions – opera houses, museums, libraries, and galleries – were created by wealthy aristocrats and industrialists in the 19th century. The more democratic civic world that emerged from the ruins of the Second World War was less accepting of such paternalism and the philanthropy of rich individuals was renamed “cultural democratisation”. As a part of the post-war Welfare State, this became state policy on both sides of the Iron Curtain, though expressed in contrasting ideological terms.

Arts Council England manages public funding for the arts in England. For some years in the 2000s, it used the slogan “Great Art For Everyone” and, essentially, that’s what cultural democratisation means. It is the idea that everyone would be better off if they had access to art. In the spirit of democracy, we avoid calling it the fine arts, but we all know what we mean. Since most people, for reasons of location, education or poverty, among others, do not attend galleries or concert halls, a variety of access, inclusion, and participation programmes are put in place to make it easier for them to do so. The original idea placed culture within the framework of public services that the state should provide for its citizens, alongside employment, health care, housing, and education. As a child of the welfare state, I believe there’s a lot to admire in that model of social democracy, even if its paternalism was rejected by the cultural revolutionaries of the 1960s.

But the problem with that model now is that neoliberalism has been dismantling the Welfare State for half a century. The idea that the state should ensure full employment would strike most people as bizarre today. When I was an apprentice community artist, 44% of the British population lived in public social housing: today it is 8%. Social services, education, and health have all seen varying degrees of privatisation in different countries. But public provision of art and culture, strangely, have grown in that period. There is no space to address that seeming paradox here, but three points can be made. First, culture has become a key driver of the neoliberal economy, inseparable from new digital means and formats of creation, production and distribution. Secondly, compared to other elements of the welfare state, public funding of the arts has a symbolic value out of all proportion to its cost. Thirdly, the arts that benefit from public funding are, as they always were, those which are valued by the elite – the fine arts which hold and add to their cultural capital. It is not a coincidence that cultural democratisation also continues to serve the interests of the people who produce, manage, and live from culture.

In the 1960s, an alternative form of cultural policy was proposed, although I argue in A Restless Art that it had roots going back to the early 19th century and might even be considered a reaction to the emerging ideas about the fine arts. Then, from Great Britain to Bulgaria, we see working people mobilising to create their own cultural and educational organisations, pooling their own resources for cultural empowerment. That idea of self-determined change coming from the grass roots was renamed “cultural democracy” in the 1960s and 1970s. The simplest way of distinguishing it from the alternative model of cultural policy is to say that if cultural democratisation is great art for everyone, then cultural democracy is art by, for, and with everyone.

Note that you cannot call it great art, because you don’t know what it is until people have made it. Consequently, you cannot presume that it will be great; it might be bad, it probably will be okay. In truth, most art is, by definition, average, whatever standard is applied to judge it. The rhetoric that inflates every orchestra, theatre company, and museum into being world class is absurd. It is not possible for them all to be world class, or the term ceases to have any meaning, except perhaps as virtual artistic imperialism. Some have to be ordinary – and there is nothing wrong with that; most of us are ordinary. Over the years, I have consistently defended a realistic understanding of what culture and art is, and does, which generally is to be good enough for its own time and situation. That is not to suggest a lack of aspiration – I have rarely met an artist, professional or non-professional, who did not want to achieve their best, and never one who felt they were good enough – but a recognition of the real worth of what is created. To give a concrete example, in valuing excessively what is truly outstanding – like the prize-winning young musician – we neglect thousands of very good musicians who learn only that they are not considered good enough. In any case, as Avram Alpert explains:

In the very act of seeking the best, we are already no longer talking about the best flautist; we are talking about the person who plays the flute best under conditions of pressure and performance. We are finding the best competitor, not the best flute player. (Alpert 2022, 57)

One indisputable consequence of the competitive nature of music education is that most people who begin formal instrument tuition as children give up playing altogether sometime between the ages of 16 and 25. All that effort, learning, and hope abandoned by a musician who is good enough to take and give great pleasure through their playing, but who is left only with a sense of failure and dislike for an instrument that stays hidden at the top of a wardrobe. In my view, if we can be good enough, then we are already doing pretty well.

Cultural democratisation and cultural democracy have been in tension since the 1960s. Indeed, in my view, the visions of culture and society that underpin these terms have been opposed since the Enlightenment, albeit in different language and forms. They certainly shaped political and cultural discourse in the 1970s and into the 1980s. (Matarasso 2019, 73-78) The problem is that few policy-makers, or even people in the cultural sector, seem to understand their meaning or importance today, although they are used, often interchangeably, to give credibility to the plans and projects of cultural institutions (Matarasso 2021, 18-21). For example, Arts Council England’s Let’s Create Strategy 2020-2030 uses the rhetoric of cultural democracy in saying that

[t]he vision of this Strategy, therefore, is of a country in which the creativity of everyone living here is celebrated and supported: in which culture forms and transforms communities, and in which cultural institutions are inclusive of all of us, so that whoever we are and wherever we live, we can share in their benefits. (ACE 2020, 62)

However, nothing in the organisation’s subsequent planning or decision-making translates into a meaningful shift from its established policy of democratisation, or great art for everyone. However, these policy ideas define real and divergent visions of the place of artists in society and they have real life consequences. If we do not understand the concepts, or how they translate into actions, in reality, we are left without being able to have effective discussion about what we’re doing and still less why.

The Benefits of Participation in the Arts and the Problem of Social Impact

I suggested earlier that, from my perspective, things have deteriorated in important ways since policy-makers got interested in participatory art and co-creation. That has happened in part, I think, because the more interested they became, the less they understood its values and processes, including how it can bring benefits to individuals. In 1997, I published the first large-scale research into the social impact of participation in the arts in Britain (Matarasso 1997). It included new studies undertaken by me and several other researchers in the UK and abroad, but it was also informed by my own experience as a community arts worker over 15 years. The research showed that there is a social impact to participation in the arts, mainly positive, but that there could also be costs (Matarasso 1997, 76-78). Put simply, people get a lot from participating in art and culture. That was positive news for the sector and widely welcomed. But two other aspects of the findings have, I believe, been widely and perhaps deliberately, misinterpreted.

The first is that many of the benefits identified in the report are associated with participation, not with art (Matarasso 1997, 83-85). The report is clear that human beings benefit from participating with other human beings in activities where we are doing and learning together. That could be sport, it could be environmental campaigns, it could be political action, it could be religious life. All of those things bring different benefits and problems. But a lot of the benefits reported in Use or Ornament? are the benefits of participation, not the benefits of art. There are specific benefits to art, and they are discussed in the report, but the critical distinction between the benefits of participation and the benefits associated with participation in artistic projects was missed by most commentators.

The second misinterpretation relates to the policy response I proposed in Use or Ornament?, on the basis that people generally do benefit from participating in cultural activity. Some people understood that to mean that it is therefore possible to ‘produce’ those benefits when people participate in cultural activity. That is completely wrong. First, it is not possible to control those benefits. Even as an artist, as a musician, you cannot control how a listener responds to what you do. Why then would you think that you could control what people feel about participating in your music project? It is simply not in the artist’s gift. Secondly, even if it were possible, why would you think you had the right to interfere in other peoples’ lives by trying to change them through your work? Although I was far more inexperienced as a researcher and naïve about politics than I am today, my report was cautious and specifically clear about this:

[I]t is necessary to stress that participation in the arts is not being advocated as a form of, still less an alternative to, social policy. The current problems of British society will not be solved if we all learn to make large objects out of papier-mâché, play the accordion or sing Gilbert and Sullivan. Nor will British culture be improved by being sold into bonded labour to a social policy master. (Matarasso 1997, 85)

In short, the arts should not be used as an instrument of social change: it is ethically unjustifiable and, even if it were not, artists are not able to achieve it. That has always been my belief and my position, and it has only become clearer as I have seen more and more initiatives that set out to do exactly that. Today, throughout Europe, and in many other parts of the world where I have worked, funding is offered to artists on the basis that their projects will produce a social outcome, benefit or change. And that, for the reasons I have just given, is both ethically and practically wrong.

What has also become clearer to me in the intervening years is how profoundly damaging that idea is, to the practice and value of co-creation, and to society more widely. The problem is that it rests on a deep, if generally unconscious, idea about society held by those who occupy positions of responsibility – not only politicians, but also people in the corporate sector, the media, the academic and educational fields, and, of course, the cultural sector, among many others. Between them they shape and organise the ways in which society functions, largely by virtue of the positions they occupy and the education that brought them there. For the avoidance of any doubt, I include myself in this group, by birth, education, culture, and profession, even if, as an artist working in co-creation, I am one of those who are able to pass relatively easily between this group, whom we might call us, the governors, and the rest of society, them, the governed.

Even if I am painting them in bold strokes, such divisions are as old as Plato, and perhaps there is no society where versions of them cannot be found. But that does not mean they should be accepted, nor that the problems that they create should be tolerated. In a still bolder, even caricatural gesture, let me suggest that those who govern tend to think of themselves in these terms: “We understand how things should be. We have good intentions and work for the common good. We are dependable, we make judicious decisions. We are the good people. We are cultured, we have taste, we understand how things should be done. And it is our responsibility to organise things for those who do not have all those things, the people whose lives need to be improved by us, because we know.”

As I said, that is a caricature, but the reality, in the arts as well as across society as a whole, is that policy is largely based on not trusting people to know what is good for them, to make good choices, to have important skills, knowledge, capabilities or even, in some cases, to have the ‘correct’ moral values. Some people will be shocked and offended at this idea, and I believe they should be: it is shocking and offensive – although not because I am expressing it, but because if even a fraction of this is true, it would raise fundamental questions about the basis of our social contract. What evidence then is there for believing it to be true, apart from my own experience of co-creation, research, and policy-making in the arts? Here is an assessment of decades of social policy in the United Kingdom, published by the Local Trust in 2021:

This is a mindset that undermines the best of intentions. It is characterised by an assumption of superiority and a fatal need to control, and just below the surface we can sense toxic undercurrents of contempt and fear. (Boyle and Wyler 2021).

All the evidence shows that it does not work, for the same reasons I just outlined about why you cannot run a cultural project and have an effect on people – you have neither the power nor the right to do so.

Cultural Participation as a Human Right

This is important, because unless we understand clearly what we are trying to do, what we are capable of doing, and what it is ethical or not ethical to do, then we end up in a marsh, lost and stuck in the mud, and doing all sorts of things badly or ineffectually. The foundation of cultural participation is anchored in Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as it has been since 1948. All European Union members are signatories and their citizens have the right to participate in the cultural life of the community. We might reasonably argue about what participating in the cultural life of the community means. For some people it means cultural democratisation, so you can go to a museum, you can go to a concert. For me, it means cultural democracy, being able to create art, being able to represent yourself in culture and being able to do it on your own terms. But either way, it is a human right. It is not a concession that is being given to some people, on the basis that it will somehow improve them or make them more acceptable as fellow citizens to the people who make the decisions. It is a human right and the basis of the concept of human rights is equality between people: not us & them, only we.

How might we get to we from us & them? The spectrum of co-creation (Figure 1) is adapted from a version in Co-Creating Opera, a short book I wrote at the end of Traction, a European research project in which I was a partner (Matarasso 2023). The spectrum is defined by who is in control of what is happening – the professional artists or the non-professional artists. Mostly, I think social inclusion projects happen towards the professional end, which is why they are rooted in us & them logic. They belong there because they are conceived by professionals and then packaged and presented to people like ready meals. There is nothing to do but consume.

Figure 1: The spectrum of co-creation. Source: Own illustration.

My Definition of Co-creation

In A Restless Art I propose that participatory art is the creation of art by professional and non-professional artists (Matarasso 2019, 48). That also applies to co-creation. There are differences of language in these terms, but I will not untangle them here. Rather, I would like you to register two things. First, co-creation is about making art. If you are not making a work of art, intended to be shared as an act of creation in the world, then you are involved in education, or social work, or something else. Unless you are making a work of art or a performance, you are not involved in co-creation, or community art, or participatory art.

The second thing about this definition is my use of the term “professional” and “non-professional artists”. I am saying that being an artist is an act in the world, not an existential condition. No-one is born an artist. That is a fiction of Enlightenment philosophers who sought to turn art into an alternative religion, because they did not like the one they had. No one is born an artist, you become an artist by doing what artists do, which is to create art. You might do it well, you might do it badly but, just as everyone in the Berlin marathon is a runner, and some of them will be world class and break records while others are only trying to finish, every one of them is a runner. When people are being artists, they are acting in the world, but doing it differently.

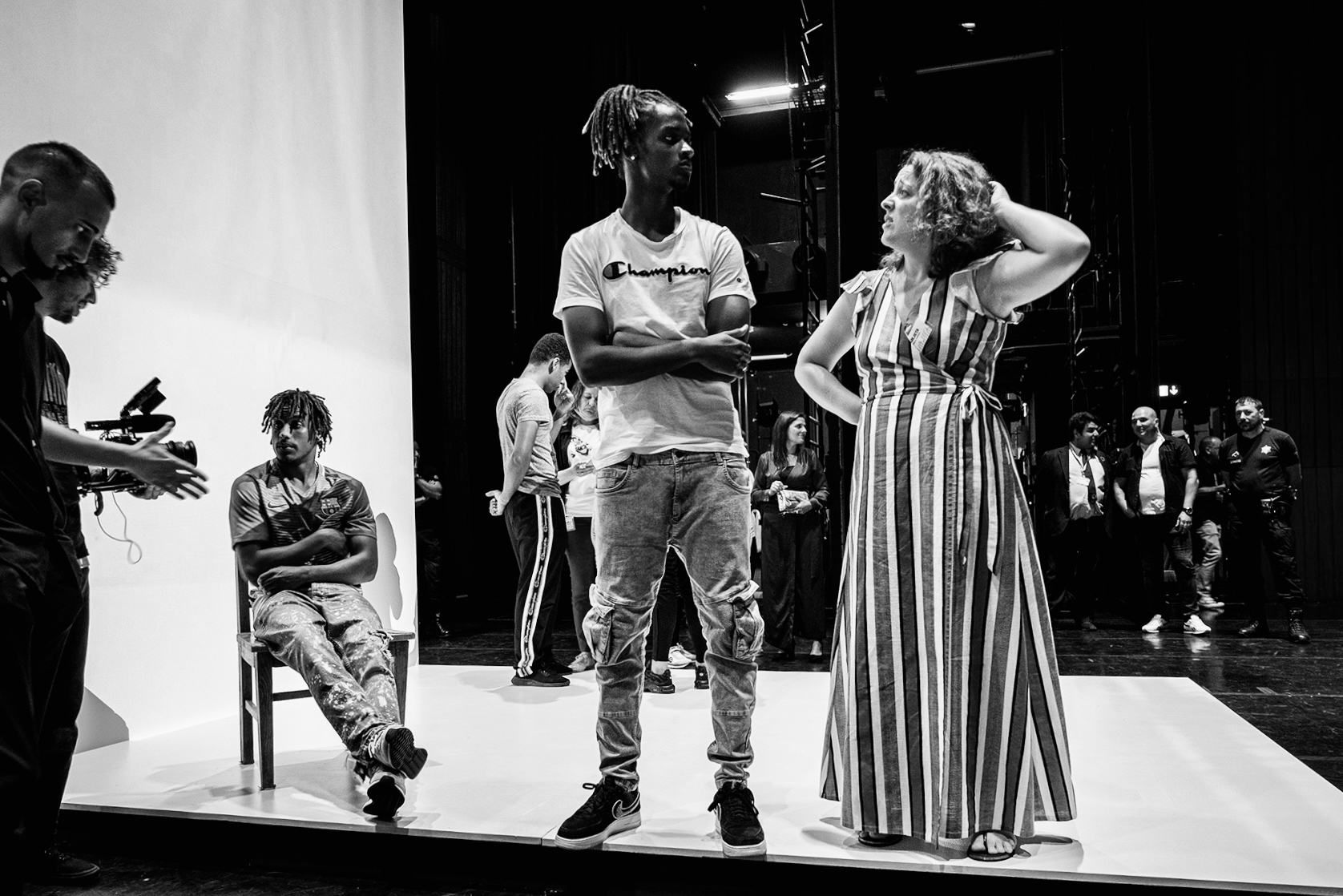

Figure 2: O Tempo (Somos Nós). Source: Joaquin Damaso SAMP.

Figure 2 is an image taken before the performance of the Portuguese prison opera, in the Gulbenkian concert hall, in June 2022. The man with folded arms is an inmate; the woman is a professional opera singer: they performed together a few hours after the photo was taken. In my terms, one is a professional artist, and the other is a non-professional artist, but both are artists in what they are doing. And when you come and see the opera, you may not know who is professional and who isn’t, depending on what is happening. Both bring capabilities to the co-creation process, but their capabilities are not the same, and it is in the differences that the unique possibilities of co-creation lie.

The professional artist has an artistic education: they have skills and expertise acquired over time. They have knowledge of their field and perhaps of the practice of co-creation, al-though that is not necessarily the case. They have experience on which to draw. They have done this or versions of this before; they have a context, they understand the field. Opera is not new to this singer. She knows her peers, she knows the standards in her field, whatever she thinks of them, and that allows her to make an informed judgement about her work and about everything that is happening. Finally, professional artists have talent.

| Professional artists | Non-professional artists |

|---|---|

| Education | An open mind |

| Skill and expertise | New ideas |

| Knowledge | Knowledge |

| Experience | Experience |

| Context | Something to say |

| Informed judgement | A need to say it |

| Talent | Talent |

Table 1: The different assets and capabilities artists bring to co-creation. Source: Own illustration.

So, what do the non-professional artists bring to that? First, they bring an open mind, akin to what Zen Buddhism sometimes calls a beginner’s mind: knowing that you do not know. That is liberating because you can ask questions. Professional artists, on the other hand, tend to think they do know. What often happens in co-creation is that the non-professional artists will ask, “Why don’t we try this?” and the professional will answer, “I don’t know, perhaps because I’ve never thought of doing it like that, or because I was taught not to do it like that, or just because it’s my habit not to do it like that” – all the practices that build up around experience.

The non-professional artists, like all human beings, also have knowledge and experience of life. This opera, after a number of false starts, settled on the story of Penelope and Ulysses, and the professional artist in this photo sang the role of Penelope. The reason it settled on that story was because it is about the experience of being separated from people you love and the life decisions you made that caused that separation. It corresponds closely to the experience of the young men detained in this prison. It is their lived experience that shapes this story and its meaning. So, they also have knowledge and experience – it is just different from that of a professional opera artist. They might not know the difference between A flat and B flat, but does it matter? They know other things that matter much more in co-creation.

Finally, because of that, they have something to say. That is not always true of professional artists, for whom each production is another job in which they may or not feel much invested. In contrast, this co-creation may be the only chance the non-professional artist will ever have to express themselves, so they will seize it. They are motivated and they know what they want to say. In truth, they are only there because they want to express themselves artistically. They want to create meaning in the world, to make sense out of their experience. And finally, non-professional artists can have as much talent as professional ones. It may not be the talent anyone expects, or that fits with established criteria, or aesthetics, but it is certainly there.

What happens when you bring these people together? Figure 3 is from the finale of the performance at the Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian in Lisbon on 16 June 2022. On stage there are many non-professional artists and four professionals, not forgetting the professionals in the orchestra and those involved in the co-creation of the libretto, the music and the production itself. Some of the families of the non-professional artists who also played a role are on the stage too. To me, the photograph is very moving: it captures a lot of contrasting emotions – pride, joy, certainly, but also sadness at the circumstances behind this performance.

Figure 3: ‘O Tempo (Somos Nós)’. Finale of the performance. Source: Joaquin Damaso SAMP.

Audre Lorde, the American poet and feminist, wrote: “Difference must be not merely tolerated, but seen as a fund of necessary polarities between which our creativity can spark like a dialectic.” (Lorde 2007, 104) There are immense social, cultural, and life differences between the people on this stage, not forgetting all those around them who are not visible in the photo. They extend to the reality that some slept at home after the performance while others slept in prison cells. Again, this is a bitter reality from which we should not turn away, either as people involved in co-creation or as human beings. At the same time, in artistic and human terms, that difference is not a liability – it is the soil from which a genuine equality can spring. It may be fragile, short-lived, and even compromised, but what matters is that, like the art work that bore it, it exists. And it is precisely because of the differences that it can happen.

The Traction Project

The opera performed in Lisbon was part of Traction, a three-year project to explore how new digital technologies could make opera co-creation accessible and relevant to people who are at risk of social exclusion. Funded by the EU Horizon programme, it was led by Vicomtech, a research institute in San Sebastián, and brought together opera producers, universities, and other partners from Ireland, Spain, the Netherlands, Portugal, France, and others. My role was to guide the co-creation processes of the three new opera productions: a virtual reality opera with rural communities by the Irish National Opera, a main stage production at the Liceu Opera House in Barcelona, and the opera developed with inmates of the prison by the SAMP community music school in Leiria, Portugal. Alongside the creative work, new digital tools were developed to support the process by the technology partners. It was a huge and complex project, made more challenging because it began in January 2020 and so coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the many restrictions, we were able to bring it to a successful outcome, with the three operas being performed between June and October 2022. A website1 was created to present the work, with videos of the operas and many other resources, among which is a book that sets out the key guidance from the project in the form of guiding principles for co-creation (Matarasso 2023).

Guiding Principles of the Traction Project

A principles-based approach is appropriate for co-creation projects, because it reflects the fundamental diversity and flexibility I see as inherent to co-creation itself. Every co-creation project is different. It is not possible to know what will happen until you know who is present and taking part. If you do know what is going to happen, it is not co-creation – you are doing a project where people are being invited to take part in an existing artistic initiative. That may be worthwhile, but it is not co-creation. Without uncertainty, you are not opening the work to other people’s creativity. Guiding principles are ways of thinking through some of the questions that arise from that necessary uncertainty. I am not sure that we got these right when we worked on them in late 2022. They are as far as we could get, but I continue to reflect on this question.

Table 2 Traction co-creation principles (Matarasso 2023). Source: Own illustration.

| Principle | Comment |

|---|---|

| Aware | because a conscious, informed understanding of people, context and actions is the foundation of good co-creation |

| Equal | because each participant has the same right to contribute to co-creation |

| Ambitious | because everyone deserves to benefit from the best process, artistic work and human outcomes |

| Honest | because integrity is the foundation of trust, learning and empowerment |

| Responsive | because complex situations require flexibility to meet changing needs and opportunities |

| Patient | because relationships, learning and growth all take the time they take |

| Hopeful | because hope in uncertainty enables us to work towards the outcomes we want |

The first principle is about being aware of the context in which you are working, and the people who are being invited to take part in the work with you. Equality is fundamental to co-creation because everyone must have the same place within it. They may bring different resources, abilities, and skills, but they have the same right to influence and to be part of the process. Of course, the work should be ambitious. There is no good reason to do less ambitious work than normal because it involves non-professionals. Honesty is essential because good intentions are not enough. Few people come to participatory or co-creation work without good intentions but they can lead to bad decisions, like telling someone that their work is good when you do not really think it is. Honesty is saying this is not yet good – this is why and here is how it could improve. Without honesty, there cannot be learning and empowerment. Co-creation must be responsive because, as we have seen, in co-creation you cannot know what will happen until it happens. If you know what is going to happen, it is like inviting people to eat a meal you have already prepared. Co-creation means inviting them into the kitchen to find out what might they want to cook. This is a key difficulty with the us & them logic, which provides funding against outputs and deadlines that cannot, and in my view, should not, be accepted. Instead, we need to begin a much more sophisticated discourse about what co-creation is, how it works and what it can achieve, if we are to change the simplistic ways it is often seen in the cultural sector and by funders and policy-makers. This approach may take longer and be more complex, but it is far more valuable. The journey is as important as the destination: neither can be good unless both are. The final principle is the one that I am least comfortable with now, because I do not feel as hopeful as I did last autumn. But perhaps that is a good lesson for me, because we will not get anywhere unless we do this work with hope in our hearts.

From Social Impact to the Capabilities Approach

As I said at the beginning, my ideas about co-creation and its socio-political context are developing as a result of the Traction project and other experiences, so I am sharing work in progress that I hope can be outlined more fully in a new book. The key problem is finding a way to escape the paternalism inherent in almost all participatory art projects financed by public or philanthropic sources – what I have called, somewhat uncomfortably perhaps, the us & them relationship. One of my key ideas for doing that is to move from thinking about social impact or even social inclusion to the capabilities approach, which has been developed over the last 25 years in the context of development by thinkers such as Amartya Sen (1992), Martha Nussbaum (2011), and others. Crucially, the capabilities approach is founded on ideas of justice and human rights, so it aligns with my belief that approaches to co-creation should also rest on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Traction aimed to advance thinking in this area by adapting the capabilities approach to the practice of co-creation. Sen and Nussbaum use the term “approach” to recognise that human capabilities are evolving and contingent, and there is no consensus as to what they should comprise in all polities and cultures. For Nussbaum, capabilities are “the answers to the question, ‘What is this person able to do and to be?’” (Nussbaum 2011, 20) There are many ways in which a person’s capabilities could be enlarged through opera co-creation, e.g. through developing skills, acquiring social capital, building knowledge or self-confidence etc. (Matarasso 1997, 2019). The capabilities approach provides a new theoretical basis for a contextual analysis of these changes. It also invites us to ask what we can do and be as human beings. What freedom do we have? If I ask myself that question, it is clear that the degree of freedom that human beings have over what they can do and be varies enormously, not only globally, but within our own societies. I am very conscious that I have benefited throughout my life from a high degree of freedom, and all I have done in my working life is the result of that privilege. Nussbaum puts our individual capabilities firmly into that social context: “[Capabilities] are not just abilities residing inside a person but also the freedoms or opportunities created by a combination of personal abilities and the political, social, and economic environment.” (Nussbaum 2011, 20) She sees that personal capabilities (such as skills, knowledge, talent or confidence) are essential but not sufficient to human flourishing. Unless a person lives in a socio-political environment that offers the freedoms and opportunities to develop and use their capabilities, their potential is limited. Women gained the right to take degrees at Oxford University in 1920. Until then (and arguably for many years afterwards) they were structurally excluded from academic and professional life, whatever their personal capabilities. So, the environment in which we live determines our capabilities. The discourse about the social impact of participation in the arts has mostly concerned the individual, which aligns it with the focus of neoliberal ideology. Nussbaum’s work shows that the social, economic, cultural, and political environment within which we try to use our capabilities is at least as important in determining the true extent of our freedom. So, in considering the social impact of Traction, we asked two research questions:

-

Has participation in opera co-creation extended the person’s capability to do and to be what they choose?

-

How far do the social entities within which participants aim to exercise their capabilities enable them to do and to be what they choose?

In fact, I think that the second of those questions is inadequate. It focused on the social entities involved in the project, notably the pera producers and voluntary organisations supporting the process, because that was the extent of the wider environment that could be reasonably considered and, more critically, the only part that might change. There have been some significant changes in that respect. For example, inmates’ regular access to the arts has increased at Leiria youth prison and the Ministry of Justice is engaged in the issue, but these positive changes have taken years and remain dependent on local managers and national policy-makers.

From Us & Them to We

Is there a path from us & them to we? Honestly, I do not know. Today, after decades working for social change through co-creation, I doubt what contribution I have made. My ambitions were modest, but perhaps even they were too great. I know that many individual people have benefited and that their capabilities have been enhanced through their participation in projects like the Traction operas. At the same time, I fear that the work has allowed the system to continue unchanged and that I may even have reinforced its us & them logic by accepting the terms on which public funding of arts projects is awarded. I have fallen into the self-deception of doing good projects and thinking it is enough. And it is not enough. A good project is no substitute for a good policy. And we lack good policy, not just in culture, but across the board. In the absence of good policy frameworks, I fear that, however good individual projects may be, all we do is alleviate symptoms without resolving their causes.

Endnotes

-

See http://www.co-art.eu/ (accessed April 9, 2025).↩︎

Bibliography

ACE. 2020. Let’s Create, Strategy 2020-2030. London: Arts Council England. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/lets-create.

Alpert, Avram. 2022. The Good-Enough Life. Princeton University Press.

Shiner, Larry. 2003. The Invention of Art: A Cultural History. University of Chicago Press.

Berry, Wendell. 2019. Essays 1993-2017. Library of America.

Boyle, David, and Steve Wyler. 2021. “‘Us and them’: A mindset that has failed our communities”, The Local Trust. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://longreads.localtrust.org.uk/2021/12/10/us-and-them-a-mindset-that-has-failed-our-communities/.

Lorde, Audre. 2007. Sister Outsider. Penguin.

Matarasso, François. 1997. Use or Ornament? The Social Impact of Participation in the Arts. Comedia.

Matarasso, François. 2019. A Restless Art. How participation won and why it matters. London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Matarasso, François. 2021. Opera Co-creation, Preliminary Report. Traction Project. Accessed April 9, 2025. http://www.traction-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2022/07/Opera-Co-creation-Preliminary-Report.pdf.

Matarasso, François. 2023. Co-Creating Opera, Guidance from the Traction Project. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://co-art.eu/content/files/co-creating_opera_guidence_from_the_traction_project.pdf.

Nussbaum, Martha. 2011. Creating Capabilities. Harvard University Press.

Sen, Amartya. 1992. Inequality Re-examined. Oxford University Press.