Pierre Carré and François Delécluse

How to cite

How to cite

Outline

Outline

Introduction

During the 1960s and 1970s, Xenakis conceived several shows which mixed music, architecture and performance; he called them ‘polytopes’. In the Polytope de Cluny (1972), in particular, the most advanced technologies of the time were employed to imagine a new synergy between music, space and light. During this 25-minute-long installation, concrete tape music flowed under the arches of the ancient Roman baths of Cluny (Paris) while interacting with visual patterns created by an array of hundreds of flashes and laser beams. In order to synchronise the diffusion of the different audio tracks among the many loudspeakers with the ballet of light, Xenakis had designed a customised technical apparatus that relied at its core on a monotasking computer to decode in real time the digital data stored on a command tape. However, the technologically avant-garde nature of this work, together with the temporary character of the show and its prohibitive cost were the very reasons why it was never played again. Due to the scarcity of the remaining original material, it was believed for a long time that the Polytope was lost. Nevertheless, the digital command tape of the show was recently rediscovered, and its cross-examination against archival documentation available at the Xenakis Archives (technical documentation, letters, photographs, videos, drawings, etc.) opened new perspectives for reconstructing the Polytope (see also Carré 2022).

The reconstruction of the spatial treatment of sound in the Polytope de Cluny provides insight into lost aspects of Xenakis’s work. Spatialisation is of crucial importance in his work, both in his electronic and instrumental music. The latter has already been the subject of several studies in works such as Persephassa (1969) or Terretektorh (1966) (Da Silva Santana 2001; Hofmann 2008; Rimoldi and Schaub 2013). The spatial dimension of Xenakis’s music has also been studied more generally (among others: Hoffmann 1998, 2008; Solomos 2015). Although space often plays a very important role, the scores of only three musical pieces contain a fixed spatialisation intended to be automated: Concret PH (1958), Polytope de Cluny and La Légende d’Eer (1978) as the musical part of the Diatope. In addition to general studies on this issue (see, e.g., Solomos 2001 and Harley 2015), the Diatope has been the subject of a particular investigation (Kiourtsoglou 2017) examining, among other things, the specificities of Xenakis’s spatialisation of sound in his electronic music. Moreover, an existing multichannel spatialised version of La Légende d’Eer performed by Xenakis himself and two other colleagues can inform us about the composer’s performance practice of spatialisation (Friedl 2015). Apart from these few studies, there is not much tangible literature on the spatial dimension of Xenakis’s electronic music. From this perspective, the study of the archives and sketches linked with Polytope de Cluny sheds new light on spatialisation. It gives us a new perspective on the composer’s thoughts about space – not so much from a philosophical point of view (already explored in the cited studies) – but specifically on his creative process and compositional approach. The exploration of Xenakis’s compositional intentions through archival material makes it possible to understand, in particular, the complex relationship between the idea of a sound movement and its realisation. This relationship is nourished not only by an abstract concept of spatialisation, but also by the inherent possibilities of the specific devices available to the composer.

Description of the Sources and Apparatus

Sources

In order to reconstruct and understand the spatial treatment of sound in the Polytope de Cluny, it is necessary to refer to a set of sources, including the sound tapes produced by Xenakis for the Polytope de Cluny, but also the digital tape with the control data for the spatialisation. In addition, the sources essential to the understanding and reconstruction of the Polytope de Cluny include an important archive file documenting the entire period of its conception and production. These sources allow us to understand in particular the structure of the control tape and the processing by the various machines, which together constitute the Polytope de Cluny. These sources provide an opportunity not only to reconstruct the work’s production process, but also to gain a deeper understanding of Xenakis’s conception of sound space in the Polytope de Cluny.

| Types of Sources | Sources | Location/Publication |

|---|---|---|

| Audio tape | 8-track audio tape (audio on 7 tracks + 1 track synchronisation signal) = Official rental material for sound projection (1972) | Paris: Salabert, XE 105 |

| Digital tape | 9-track digital tape = Control tape (1973) | Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, département de l’Audiovisuel, fonds Xenakis, DONAUD0602_000613 |

| Technical drawings and tracing paper | Autograph drawings (p. 1) and tracing paper (pp. 2–4) on speaker placement and sound paths | Paris: Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 22–2 |

| Photographs | Photographs of the Polytope de Cluny (1972–1974) | Paris: Collection Famille Xenakis DR |

| Notes, reports, correspondence |

Autographic notes on the Polytope de Cluny, notably including: – pp. 13–19: project for the “armoire de commande” (electronic apparatus) – pp. 67–69: cost estimate – pp. 167–176: description of the control software by Robert Dupuy – pp. 218–220: instructions for the operator – pp. 221–227: description of the control tape data – pp. 237–238: improvements proposed by Bruce Rogers |

Paris: Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 22–3 |

| Advertising brochure | Ampex: TM-7 Digital Tape Transport, TM-7200 Tape Memory System = Advertising brochure for the tape machine Ampex TM-7 (1964) | Culver City: Ampex Corporation |

| Advertising poster | Advertising poster for the Polytope de Cluny (ca. 1973) | Paris: Collection Famille Xenakis DR |

Table 6.1: Sources of the Polytope de Cluny linked with the spatialisation device.

The Command Chain

Figure 6.1a: Sound diffusion system of Polytope de Cluny, Collection Famille Xenakis DR. The upper loudspeakers are highlighted by dashed lines, the lower ones by continuous lines. Annotations by the authors.

The two main sources, the sound tape and the control tape, were read simultaneously and their output assembled by a rather complex electronic device. It linked the information of the control tape with the loudspeaker devices, which are an integral part of the spatial design.

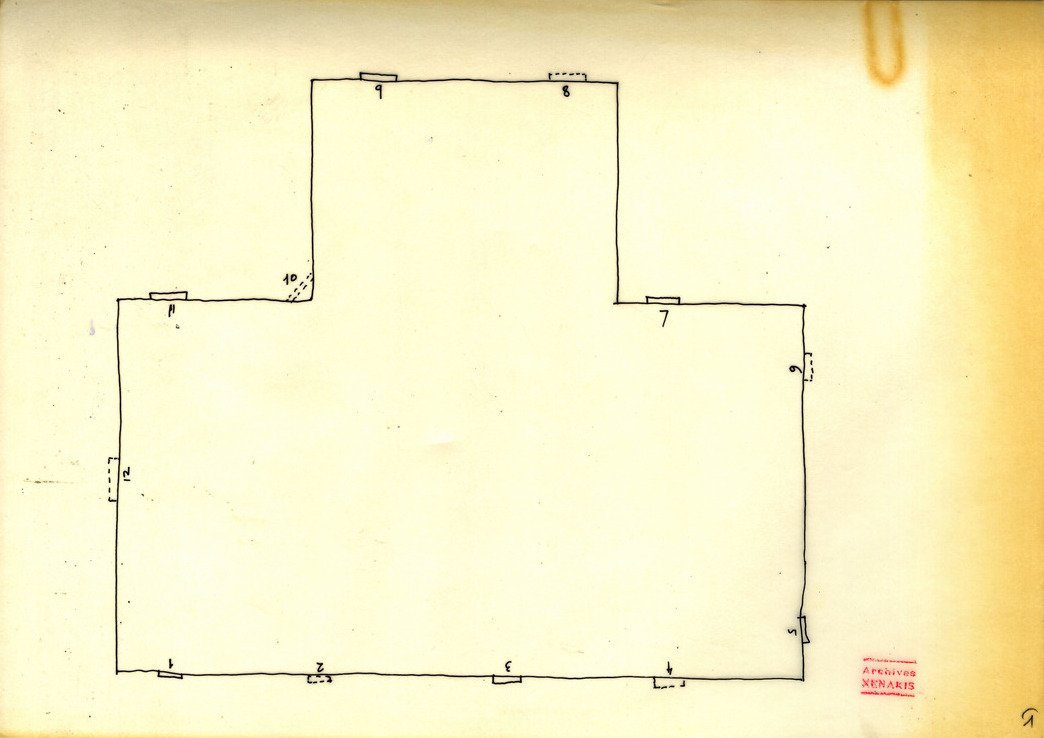

Sound diffusion was provided by 12 2 × 2 m Tannoy 15ʹʹ loudspeakers distributed in two sets of six loudspeakers each, one mounted at 2.5 m from the floor, the other at 8.5 m, as shown in Figures 6.1a and 6.1b. This equipment was not free of defects: Several were reported in the technical documentation, especially concerning low-frequency reproduction, loudspeaker saturation, crackling and noise. Furthermore, even set at −∞ dB, the loudspeakers produced a low-volume sound, as several documents point out (Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 22-3).

Figure 6.1b: Iannis Xenakis, top view of the loudspeaker positions of Polytope de Cluny, upper ones indicated by dotted lines, lower ones by continuous lines, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 22-2, p. 1.

The playback system consisted of several devices linked together, allowing the synchronisation of the whole show: an Ampex MM-1000 8-track audio tape player (Figure 6.2, on the left in the foreground), an Ampex TM‑7 9-track digital tape player (Figure 6.2, on the right in the foreground), as well as a “control cabinet” (“armoire de commande”) – allowing us to interpret the data read by the latter (Figure 6.2, in the background on the right) – and 12 power amplifiers that send the computed sound signals to the loudspeakers (Figure 6.2, in the background on the left).

Figure 6.2: Inside view of the control cabin, ca. 1972, collection Famille Xenakis DR. Photomontage and annotations by the authors.

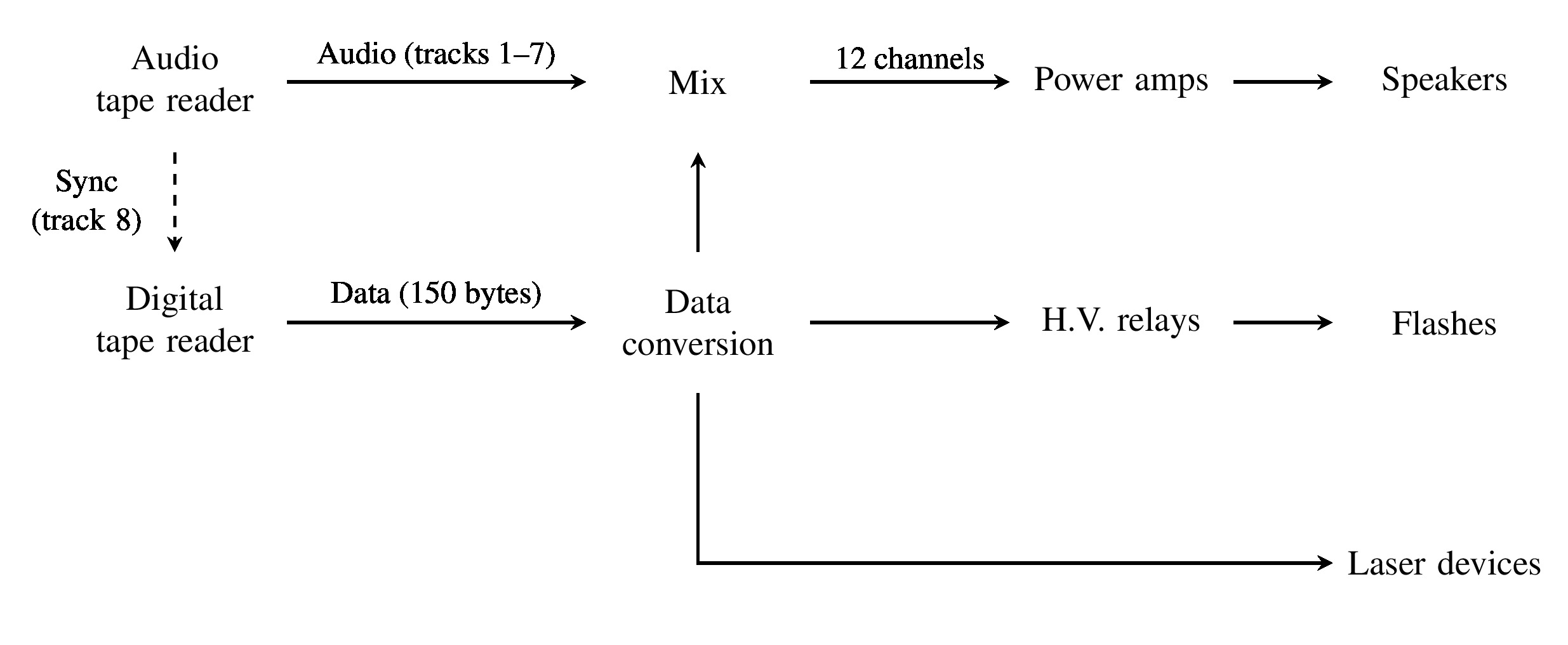

The 8-track audio is composed of seven audio tracks and one track reserved for a synchronisation signal for the other devices. The audio signal of the seven tracks was routed to 12 channels in real time and sent to the speakers. This dynamic routing made use of the digital devices (inside the “control cabinet”) to interpret the spatialisation data contained on the control tape; thus, without the latter, the sound spatialisation could not be restored.

The control tape is a magnetic media intended to be read by a digital device, i.e., the signals it contains are interpreted as binary data. The medium is rather particular: a 9-track 1/2ʹʹ, tape, which was introduced by IBM in 1964, but had fallen into disuse by the end of the 20th century. It consists of eight data tracks and one so-called ‘parity’ track used for the correction of reading errors. For the Polytope de Cluny, the medium was used in a nonstandard way: The ninth track contained a signal delimiting data blocks of 150 bytes each to be read at a rate of 24 blocks per second. These data were used to control the “ballet of lights” (flashes and lasers), but also to spatialise the sound.

An electronic circuit converted the data written on the digital tape in order to transmit them to the optical and audio devices. The circuits as well as the construction plans of this data-conversion equipment have disappeared. Nevertheless, the notes and the specifications preserved in the archives make it possible to reconstruct the functioning of the missing parts. Figure 6.3 shows the functioning of the complete playback chain (for a description of the elements controlling the light equipment, see Carré 2022).

Figure 6.3: Control chain. Diagram by the authors.

Synchronisation

Various proposals for technical details drawn up in 1972 show that initially a synchronisation system between the two different Ampex tape machines – the analogue and the digital one – had been planned. The eighth track of the analogue audio tape, which had been reserved for this purpose, was to contain a continuous series of 1000 Hz pulses spaced at 1/25 s. This signal, monitored by an electronic circuit, would have triggered the playback function on the TM-7 digital player. The tape machine would then automatically stop after reading a 150-byte block, either by incrementing a counter or by detecting an end-of-block signal on the ninth track, and wait for the next pulse to start reading the next block, repeating the read/stop cycle 25 times per second. This system would have allowed precise coordination between the audio signals on the one hand, and the light and spatialisation control data on the other.

This solution was, however, not implemented, as Jacques Pervillé, design engineer on the second version of Polytope de Cluny, confirmed.1 This was probably also the reason why the eighth track of the audio tape of Éditions Salabert is blank. Indeed, the drafts mention the use of a tape drive capable of playing at 45 ips (inch per second). The standard Ampex TM-7 tape machines are capable of 36 ips, but “special speeds [are] available to 45 ips maximum” (Ampex Corporation 1964: 4). The digital magnetic tape is encoded with a density of 800 bpi (bits per inch), so reading a 150-byte block of data required 1/30 s; however, the reader’s manual indicates that starting and stopping the machine requires up to 10 ms, which means the reading time of a block of data would exceed the limit of 1/25 of a second. The envisaged synchronisation solution could probably not be implemented because of this technical limitation of the hardware, which was not fast enough to perform stop and resume reading cycles.

Regardless of the reason, no automatic synchronisation system was put in place.2 Consequently, as we learn from the playback sheet of the operator who was in charge of launching the show, the synchronisation of the start was done manually.3 Knowing that the two tape machines were not synchronised, the rate at which the control data was read still remains to be determined. The knowledge of the playback speed of the digital tape machine is fundamental for the appropriate rate of the lighting effects, and the exact correspondence between the sound material (the audio tracks) and their spatialisation. For a TM-7 player equipped with the “special speed” at 45 ips, the digital scroller would update the data 30 times per second for a total show duration of 18ʹ40ʹʹ. On a standard player, on the other hand, the 36-ips playback results in a refresh rate of 24 cycles per second for a total duration of 23ʹ30ʹʹ. The audio tape has a duration of approximately 24ʹ30ʹʹ, so the 36 ips seem to be closer to this. Also a “25th of a second digital tape” playback was advertised on the show poster (Collection Famille Xenakis DR, not inventoried).

However, since there was no synchronisation between the devices, the timing between the sound material on the one hand, and its spatialisation on the other hand, was subject to the reading uncertainties of the control tape. The playback speed of the TM-7 could deviate up to eight per cent (Ampex Corporation 1964: 4), corresponding, in the worst-case scenario, to an advance or a delay of about 1ʹ55ʹʹ between the control tape and the soundtrack. Of course, these shifts would have had an impact on the spatialisation, since the mix data was stored on the control tape. Two cases were then possible: Either – if the digital tape was running too fast – the whole show finished too soon, the soundtrack not being played to the end, or – in the opposite case – the light show continued after the soundtrack had already stopped. This is exactly what happened in the concert situation: According to Jacques Pervillé, these shifts were indeed frequent.

Command Data

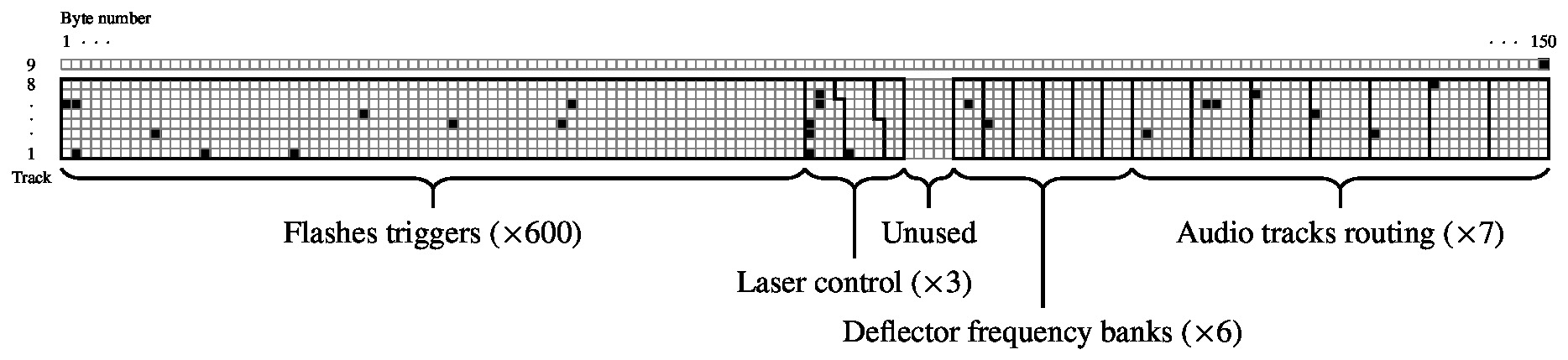

In order to understand the storage of data on each frame of the digital control tape, it was necessary to refer to the technical documentation describing the data of the control tape (Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 22-3, pp. 221–227). This description gives us more precise details about the organisation of each frame (see Figure 6.4): The first 75 bytes of each frame control the flashes; the following ten control the lasers; five bytes are unused, then the following 18 control the deflectors of the three lasers. The last 42 bytes, organised in seven groups of six bytes, contain the information for the sound spatialisation: Each group of six bytes corresponds to the routing of one of the seven tracks on the 12 loudspeakers according to four possible sound levels described in the documentation (0 dB, −2 dB, −7 dB and −13 dB). The activation of one of these bytes sends the corresponding signal of the track to one of the 12 loudspeakers at one of the four given levels (which makes a total of 4 × 12 = 48 bits = 6 bytes). It should also be noted that by default (i.e., if no bit is set) the track is not sent to any loudspeaker, which in practice adds a fifth sound level at −∞ dB. The interpretation of this data allows us to reconstruct the temporal evolution of the routing of the tracks throughout the show and thus to restore the original spatialisation.

Figure 6.4: Structure of the control tape frames, here: frame 820. Diagram by the authors.

Thought of Sound Space

Notation of Sound Spatialisation: Tablature and Score

The understanding and reconstitution of a work such as the Polytope de Cluny are notably linked to the nature of the notation for machines. The Western musical writing tradition has two main categories of writing: tablature and score. Tablature is a system of notation for an instrumental piece that indicates fingerings and rhythms on a schematic representation of an instrument. In contrast, a music score brings together the different parts of a single work by indicating pitches, rhythms, timbres and intensity, without any concern as to how they are produced. This way of thinking about writing, which opposes tablature and score, corresponds to the opposition between machine thinking based on the device, on the one hand, and compositional thinking as a written sound intention, on the other. In the case of the tablature, it is a question of how to play a particular device. In the case of the score, it is a question of thinking about the resulting positions and trajectories of the sound and light material.

The control tape used in Polytope de Cluny to command the ballet of lights and the sound trajectories is similar to a tablature. There is no score pointing out what movements Xenakis wanted; the control tape is a tablature, indicating how to realise the different positions and trajectories. This tablature is intended for a single ‘instrument’, that of the light and sound device set up in 1972. In other compositions Xenakis alternates between the two types of notation: tablature and score. For Concret PH, created for the Philips Pavilion in 1958, Xenakis developed a notation of sound trajectories and not a tablature of loudspeaker signals (see Figure 6.5).

In this graphic score, we can observe a schematisation of the sound trajectories in space as well as a temporal sequence listing the different events. Thus, the slashes that can be seen on the right side of the example describe the movement of the different sound tracks according to a given trajectory, speed and recurrence; Xenakis created a graphic code to design his score and to make it readable for everyone.

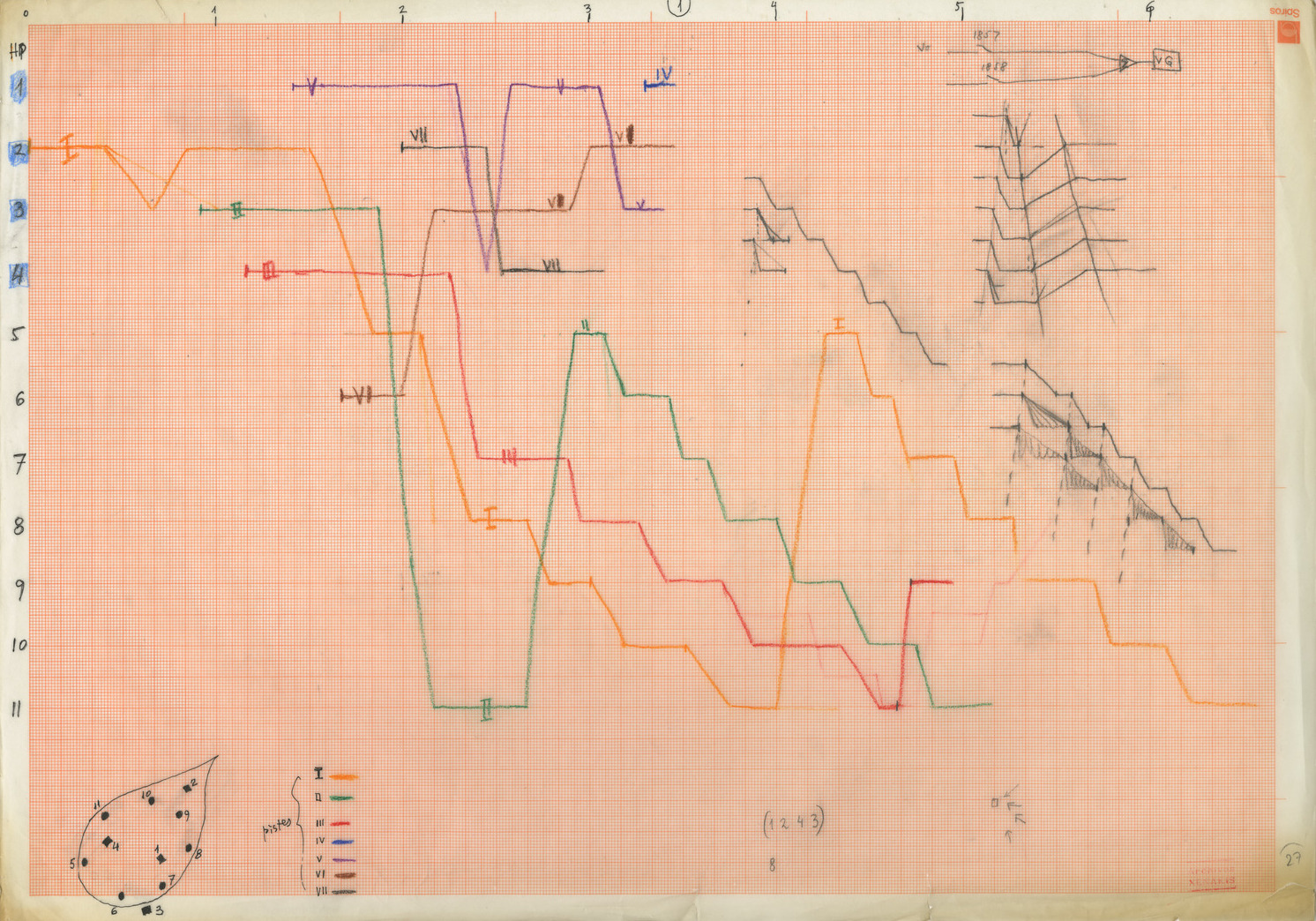

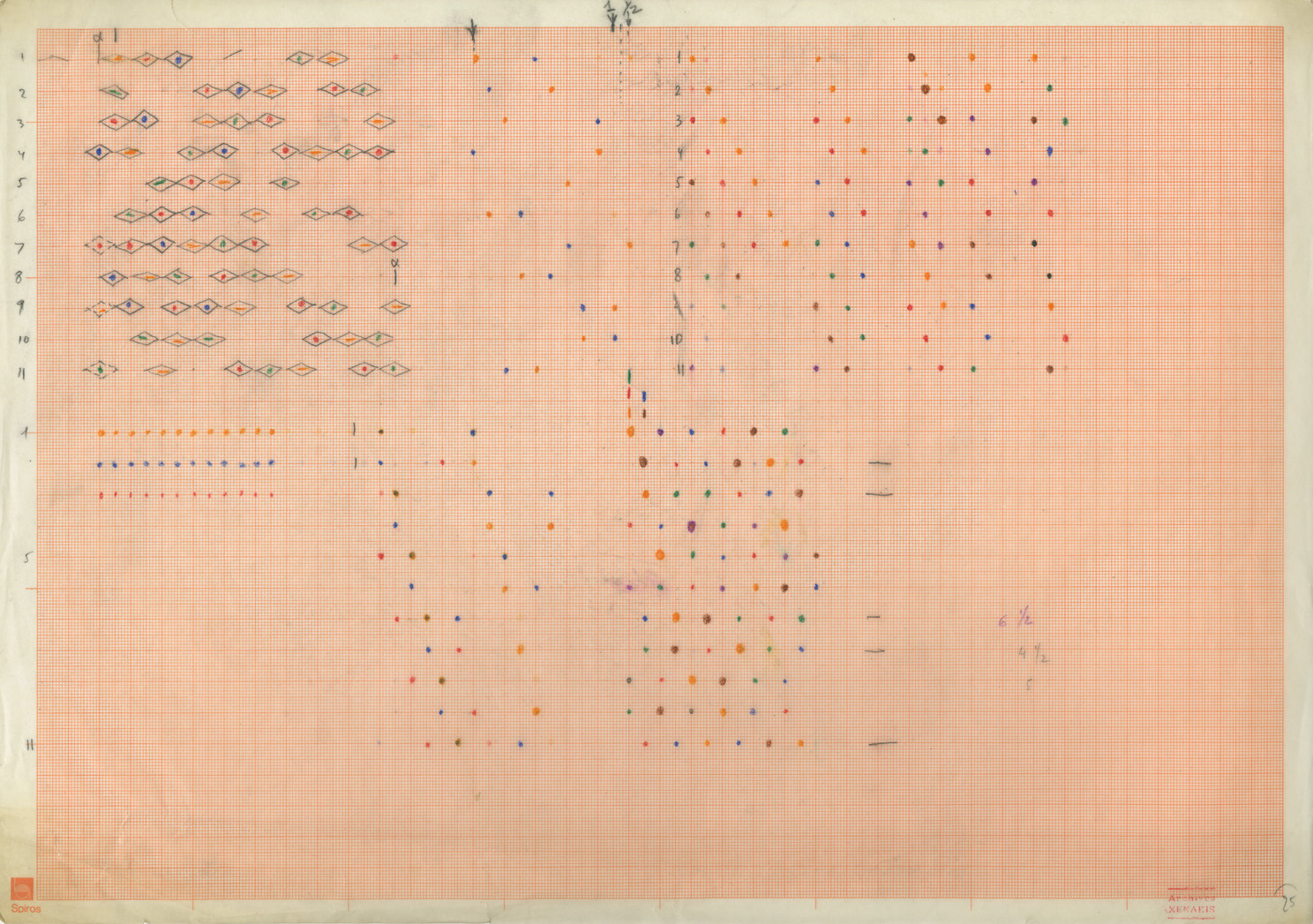

The design of the sound movements is traceable in the sketches of some of the works. In particular, in regard to La Légende d’Eer, a piece composed about six years after Polytope de Cluny, several sketches allow us to understand how Xenakis thought about spatialisation. The sketches of La Légende d’Eer (Figure 6.6) show a thought from the sound source (i.e., an abstract compositional thought) in the form of a movement of a track from one loudspeaker to another. In the upper sketch of Figure 6.6, each line (of different colours) shows the displacement of a track on different loudspeakers.

In the lower sketch, the data is not written track by track, but speaker by speaker, which is closer to a tablature, a pragmatic concept for a precise device. In the conception phase, Xenakis seems to alternate between thinking in abstract movements of sound and concrete thinking regarding the available device.

Figures 6.5a and 6.5b: Iannis Xenakis, Concret PH, graphic scores for the sound spatialisation, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, pp. 1f.

Figure 6.6a and 6.6b: Iannis Xenakis, La Légende d’Eer, sketches for the sound spatialisation, collection Famille Xenakis DR, XA 11-7, pp. 27 and 25.

Aspects of the Genesis of the Spatialisation in the Polytope de Cluny

Even if there are less traces of such work concerning the Polytope de Cluny, one can easily make the hypothesis that the genesis of the work must have been conceived, to a certain extent, through the abstract design of sound trajectories independent of the diffusion device. Several elements resulting from the analysis of the tape, the archive sources and the control program allow us to corroborate the back and forth between the imagination of the moving sounds on the one hand and a thought in respect to the unique ‘instrument’ for which Xenakis conceived the Polytope de Cluny on the other hand.

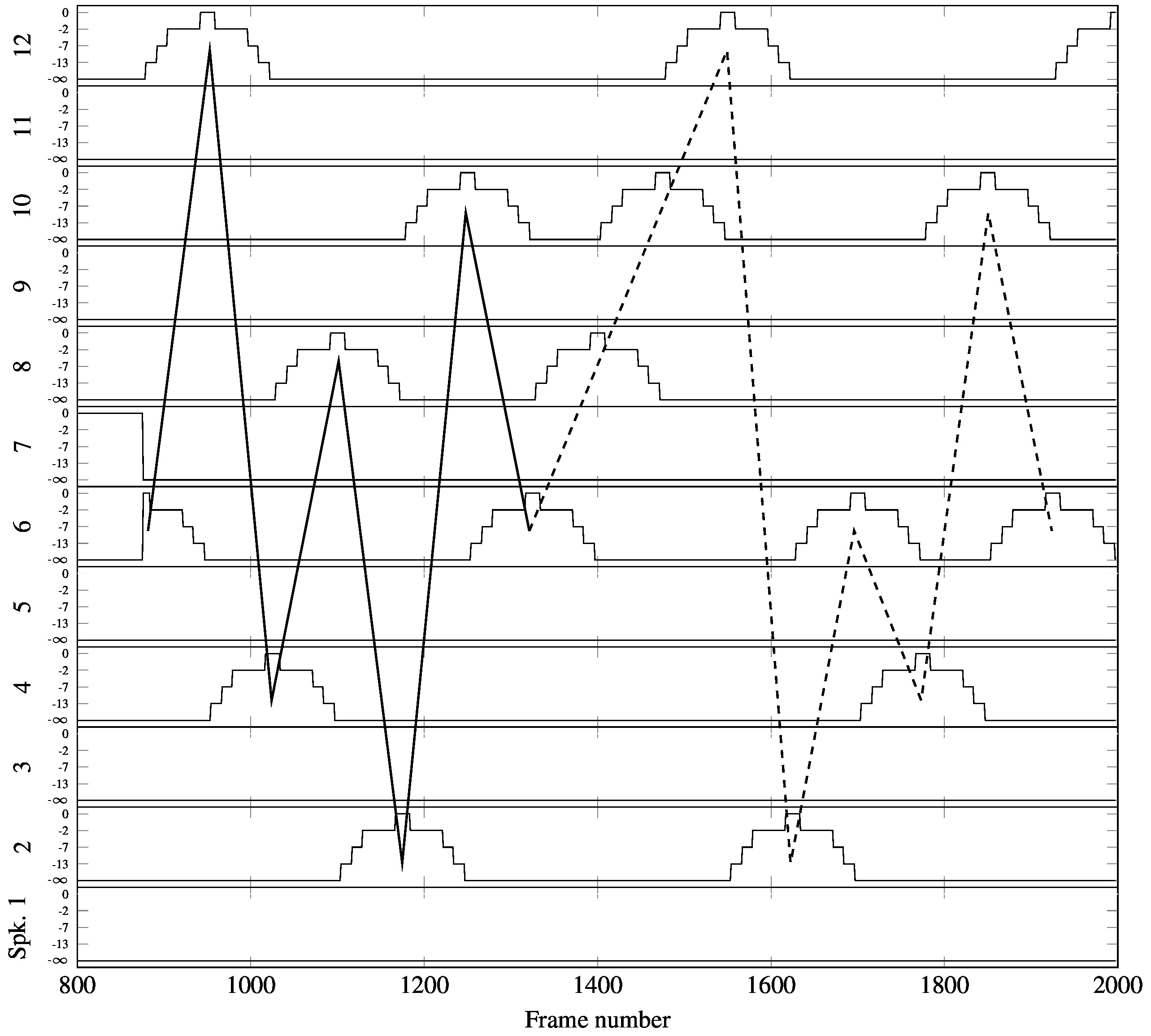

Figure 6.7a: Automation curves on the command tape, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, département de l’Audiovisuel, fonds Xenakis, DONAUD0602_000613. Diagram by the authors.

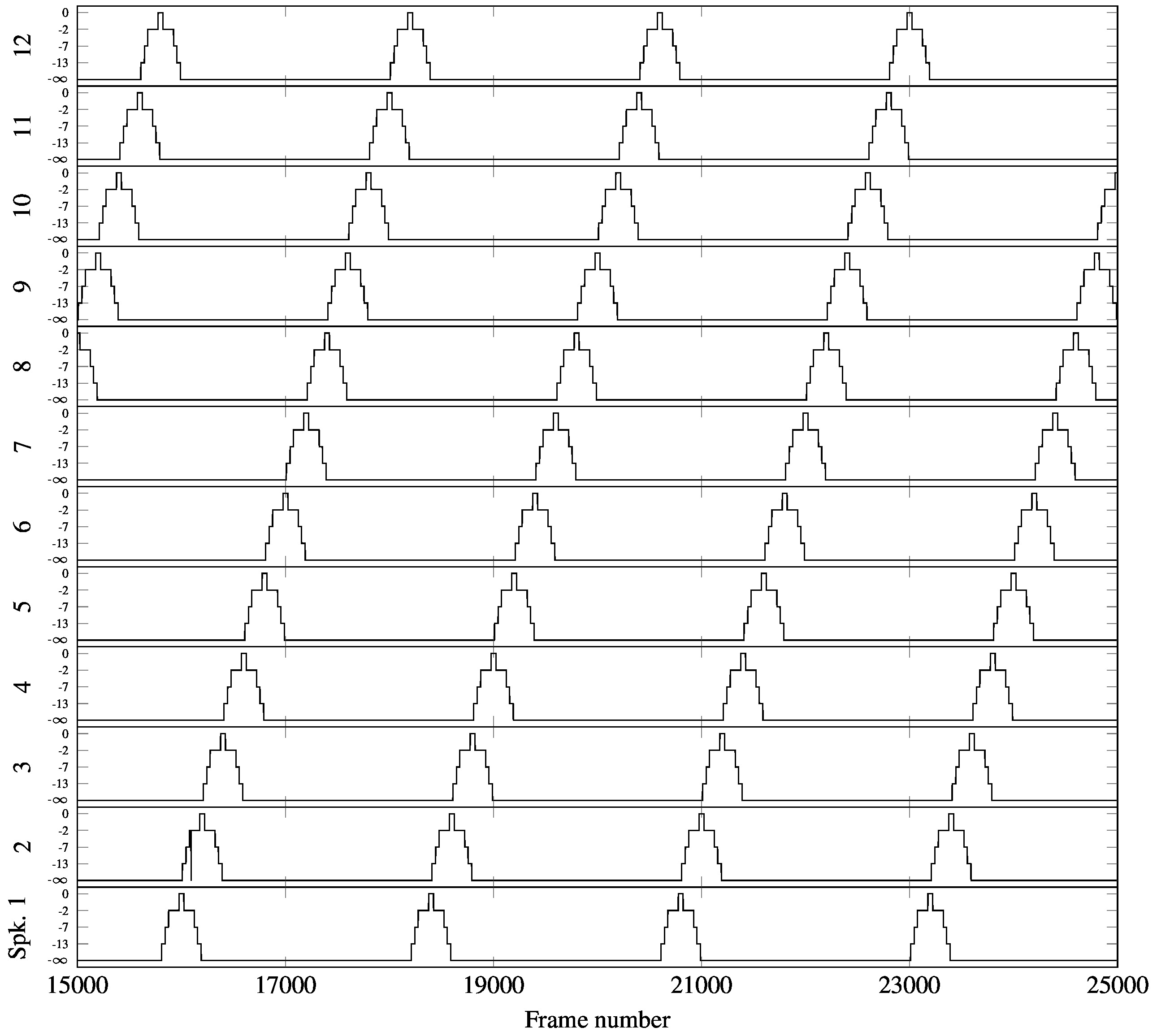

The analysis of the soundtrack clearly shows displacements of sound sources that must have been conceived by Xenakis at an earlier stage of the piece’s conception. From the analysis of the control tape data, it is possible to identify regular patterns. For instance, for track 3, the data found between frames 15,000 and 25,000 (i.e., between 10ʹ25ʹʹ and 17ʹ22ʹʹ) can easily be interpreted as the flow of a sound in an anticlockwise movement, jumping between the upper and lower rings of loudspeakers with a period of 1 min 45 s (Figure 6.7a).

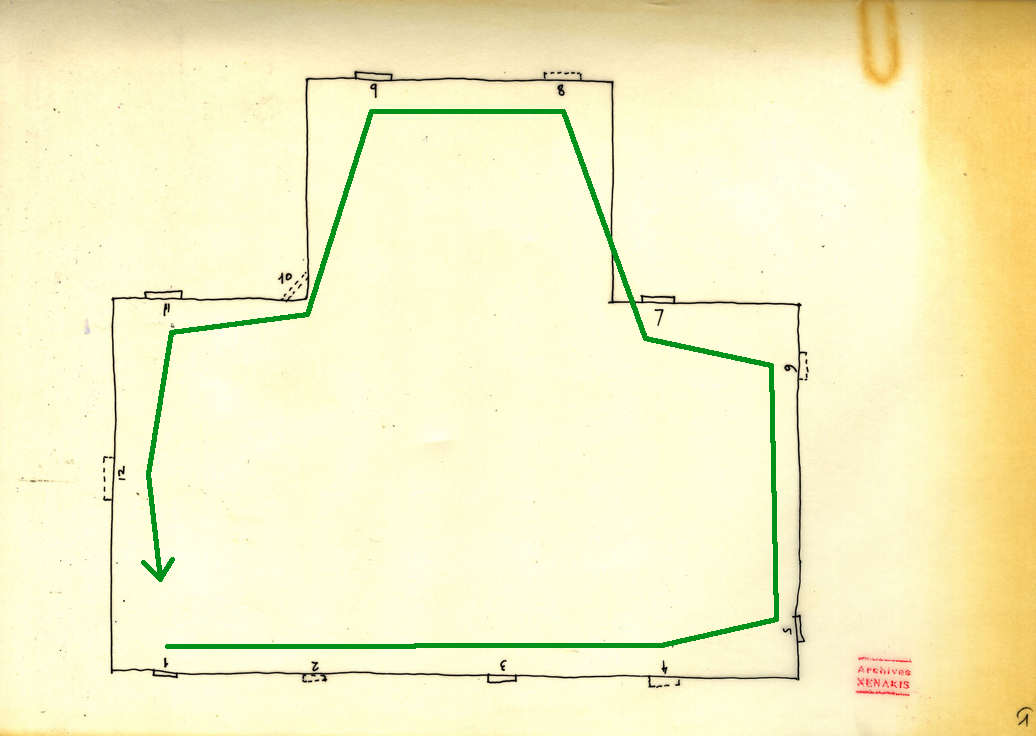

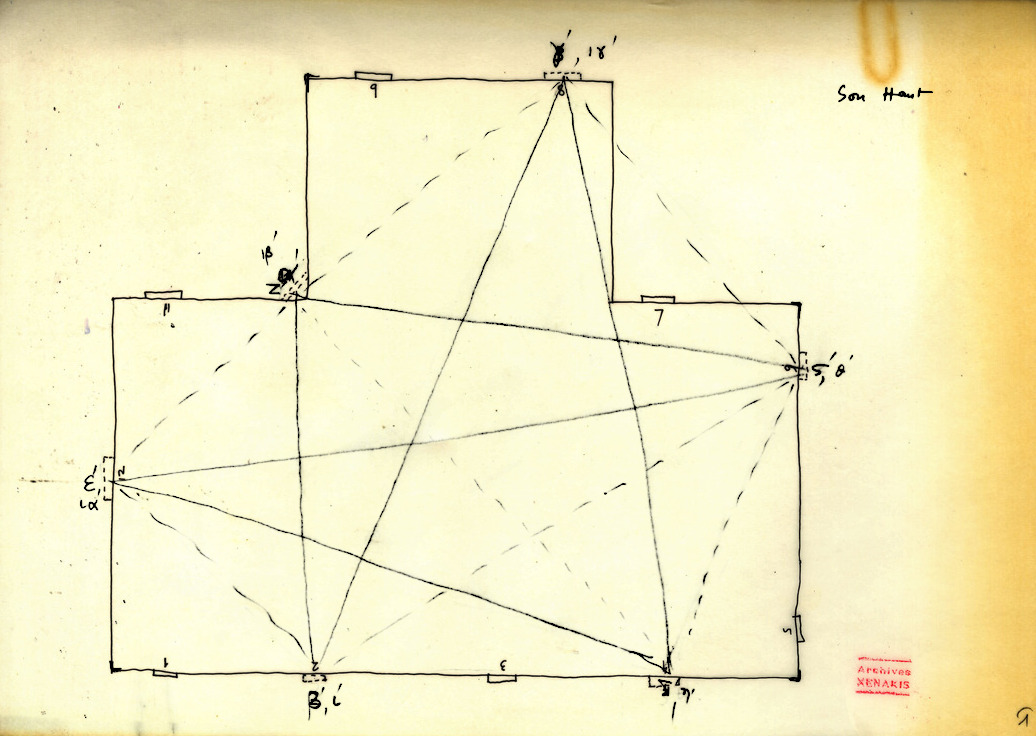

Each line corresponds to a loudspeaker numbered from 1 to 12. Changes in each line represent intensity variations from silence to full amplitude. If we depict these data looking down on the hall (Figure 6.7b), we clearly see an anticlockwise movement. This type of movement, which can easily be reproduced on another device, bears witness to a way of thinking about the moving sound source that is not specific to the Polytope de Cluny.

Figure 6.7b: Anticlockwise motion of the sound spatialisation, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 22-2, p. 1. Annotations in green by the authors.

Moreover, it can even be said that certain sound movements would not be transcribed on a device other than the 12 loudspeakers used by Xenakis. Indeed, in the archives, there are several documents that represent the sound movements according to the specific device in place (Figure 6.8b). Xenakis connects the loudspeakers positioned at the top with a drawing, the layout of which can be found by interpreting the control tape. If we look at the spatialisation data of track 1 between frames 800 and 2,000 (i.e., between 33ʹʹ and 1ʹ24ʹʹ), we find complex movements of sound which, according to several patterns in the upper crown of the speakers, seem to bounce from wall to wall (Figure 6.8a).

Figure 6.8a: Automation curves on the command tape, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, département de l’Audiovisuel, fonds Xenakis, DONAUD0602_000613. Diagram by the authors.

These patterns follow a displacement that can be found in graphic form in the sketches: The continuous lines correspond to a moving cycle between loudspeakers 6-12-4-8-2-10-6, while the dotted lines correspond to the displacement between loudspeakers 6-8-10-12-2-6-4-10-6 (Figure 6.8b). While there is a graphic design that documents the way in which Xenakis imagines sound movement, it demonstrates that Xenakis thinks of sound movement in terms of the device in place, namely the two loudspeaker crowns in specific places, and not as an abstract sound movement detached from the place and the ‘instrument’: the technical devices to realise that sound movement.

Finally, it seems particularly important to link the study of the spatial treatment of sound in the Polytope de Cluny to that of the Diatope, whose study of the sources (Kiourtsoglou 2017) has shown, among other things, that Xenakis’s thought is strongly marked by a graphic and geometric conception of movement. The same graphic and geometric notions (see Figures 6.6, 6.7 and 6.8) allow Xenakis to imagine sound movements based sometimes on an abstract concept, sometimes on the specific possibilities of a device at his disposal, thus they can change from one project to another.

Figure 6.8b: Iannis Xenakis, Polytope de Cluny, sound trajectories, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 22-2, pp. 1f. Montage by the authors.

The ambivalence of Xenakis’s sound movement thinking is mirrored in the control program itself. In the description of the control program, Robert Dupuy, the computer engineer in charge of developing the programming tools for the Polytope, defines an ‘input language’ used to provide computer functions for writing the various light and sound effects (Figure 6.9).

Figure 6.9: Description of the control software by Robert Dupuy, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 22-3, pp. 172f., detail.

Two functions concern sound spatialisation, called “(HP1) Haut-parleurs 1ère manière” and “(HP2) Haut-parleurs 2ième manière”. These two different functions permit spatialisation of sound either according to a trajectory or according to direct mixing. The first function (HP1) consists of translating the trajectory of a sound source (i.e., a track of the audio tape) onto a predefined loudspeaker circuit with a given speed. The user then enters, in addition to the date and duration of the effect, the identifier of a predefined loudspeaker circuit, the duration of a cycle and the starting point. The second function is used directly to route one of the tracks to a loudspeaker: The user assigns a track number to a loudspeaker as well as the start and end sound levels that will be interpolated for the defined duration. Even if this is only the provisional version of the program – the final program is not preserved – these two opposite approaches described by Robert Dupuy were probably each used by Xenakis depending on the effects he wished to achieve.

By analysing the control tape and the automation curves, it is possible to reimagine how Robert Dupuy’s program was able to perform the spatialisation. For this purpose, let us reconsider the example given in Figure 6.7, which corresponds to the anticlockwise movement of audio track 3 over all the loudspeakers. Based on the description of the computer language reproduced in Figure 6.9, we could, for example, propose the following instructions for realising the above excerpt:

p1: 4 (HP1)

p2: 15,000

p3: 10,000

p4: [identifier for spatialisation circuit 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-11-12]

p5: 2,520

p6: 8

p7: 3

where the time variables are specified in frame units (1/24 s). The mixing of the tracks on the loudspeakers would then have been obtained by amplitude panning between two consecutive loudspeakers in the circuit, performed on the discrete scale of sound levels available on the control system (0 dB, −2 dB, −7 dB, −13 dB and −∞ dB). In other words, to simulate the movement of the sound source between two loudspeakers, the program would generate stepwise fade-in/fade-out effects, allowing the realisation of the acoustic idea of displacement on the limited system available to Xenakis for the Polytope. This would explain the crescendo/decrescendo relays occurring in the spatialisation data, of which Figures 6.7a and 6.8a are characteristic examples.

This reconstruction of the programming remains hypothetical, but it is not unlikely that the realisation of the sound movements was conceived in the manner described above. It enables us to distinguish Xenakis’s artistic and musical idea from its realisation, that of the Polytope de Cluny. This concept of movement preceding the realisation through a specific program and device can then be compared with the ones in other instrumental or electronic works, notably orchestra compositions, like Terretektorh, or other spatialised compositions such as Persephassa or Concret PH and La Légende d’Eer.

Conclusion

Reconstituting both sound and visual aspects of the Polytope de Cluny led to a re-enactment of the show for a series of performances in the ‘Espace de Projection’ at IRCAM, Paris in July 2022. Further on, a concert version of the spatialised musical part was presented at the Klangtheater of the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna during the Xenakis 2022 Conference ‘Back to the Roots’ in May 2022. These performances have made it possible for the first time in 50 years to rediscover a show of which only photographic traces and a stereophonic recording remained. Furthermore, the study of the sources and the analysis of the control tape offer insight into Xenakis’s thinking about sound and space and can provide a framework for performers of his electroacoustic music. Finally, it is promising to compare the spatialisation concepts in his electroacoustic works such as Polytope de Cluny with those in his instrumental works such as Persephassa or Terretektorh: We find, for example, very characteristic circular sound movements at different speeds, which might be an indication of a common spatial concept in both fields.

Endnotes

-

Testimony of Jacques Pervillé, interview with Pierre Carré, March 17, 2021.↩︎

-

Testimony of Bruce Rogers, interview with Pierre Carré, 30 November 2021.↩︎

-

The instruction sheet of the operator preserved in the Collection Famille Xenakis DR (OM 22-3, 218–220) does indeed indicate: “Send simultaneously the Ampex sound (play) [and] the Ampex light (remote)”.↩︎

Bibliography

Ampex Corporation (1964) Ampex: TM-7 Digital Tape Transport, TM-7200 Tape Memory System, Culver City: Ampex Corporation; https://archive.org/details/TNM_TM-7_digital_tape_transport_TM-7200_tape_memo_20171204_0060/mode/1up (accessed March 20, 2023).

Carré, Pierre (2022) “Polytope de Cluny: Towards a Reconstitution”, in Proceedings of the Centenary International Symposium Xenakis 22. May 24–29, 2022, Athens and Nafplio, ed. by Anastasia Georgaki and Makis Solomos, Athens: Spyridon Kostarakis, 454–466.

Da Silva Santana, Helena Maria (1998) “Terretêktorh: Space and Timbre, Timbre and Space”, in ExTempore, A journal of Compositional and Theoretical Research in Music, 9/1, 12–36.

Friedl, Reinhold (2015) “Towards a Critical Edition of Electroacoustic Music: Xenakis – La Légende d’Eer”, in Iannis Xenakis. La musique électroacoustique/The electroacoustic music, ed. by Makis Solomos, Paris: L’Harmattan, 109–122.

Harley, James (2015) “Orchestral Sources in the Electroacoustic Music of Iannis Xenakis: From Polytope de Montréal to Kraanerg and Hibiki-Hana-Ma”, in Iannis Xenakis. La musique électroacoustique/The electroacoustic music, ed. by Makis Solomos, Paris: L’Harmattan, 15–18.

Hoffmann, Peter (1998) “L’espace abstrait dans la musique de Iannis Xenakis”, in L’espace: Musique/Philosophie, ed. by Jean-Marc Chouvel and Makis Solomos, Paris: L’Harmattan, 141–152.

Hofmann, Boris (2008) Mitten im Klang. Die Raumkompositionen von Iannis Xenakis aus den 1960er Jahren, Hofheim: Wolke.

Kiourtsoglou, Elisavet (2017) “An Architect Draws Sound and Light: New Perspectives on Iannis Xenakis’s Diatope and La Légende d’Eer (1978)”, in Computer Music Journal 41/4, 8–31.

Rimoldi, Gabriel, and Schaub, Stéphan (2013) “Variações sobre o Espaço em Terretektorh (1965–66), de Iannis Xenakis”, in Opus 20/2, 9–32.

Solomos, Makis (2001) “The unity of Xenakis’s instrumental and electroacoustic music: The case for ‘Brownian Movements’”, in Perspectives of New Music 39/1, 244–254.

Solomos, Makis (2015) “The complexity of Xenakis’s notion of space”, in Komposition für hörbaren Raum. Die frühe elektroakustische Musik und ihre Kontexte/Compositions for Audible Space. The Early Electroacoustic Music and its Contexts, ed. by Martha Brech, and Ralph Paland, Bielefeld: transcript, 323–337.

List of Figures

Figure 6.1a: Sound diffusion system of Polytope de Cluny, ca. 1973-1974, Collection Famille Xenakis DR. Annotations by the authors.

Figure 6.1b: Iannis Xenakis, Top view of the loudspeaker positions of Polytope de Cluny, ca. 1972, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 22-2, p. 1.

Figure 6.2: Inside view of the control cabin, ca. 1972, collection Famille Xenakis DR. Photomontage and annotations by the authors.

Figure 6.3: Control chain. Diagram by the authors.

Figure 6.4: Structure of the control tape frames, here frame 820. Diagram by the authors.

Figures 6.5a and 6.5b: Iannis Xenakis, Concret PH, graphic scores for the sound spatialisation, April 1958, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, pp. 1f.

Figure 6.6a and 6.6b: Iannis Xenakis, La Légende d’Eer, sketches for the sound spatialisation, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, XA 11-7, pp. 27 and 25.

Figure 6.7a. Automation curves on the command tape, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, département de l’Audiovisuel, fonds Xenakis, DONAUD0602_000613. Diagram by the authors.

Figure 6.7b: Anticlockwise motion of the sound spatialisation, 1972. Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 22-2, p. 1. Annotations in green by the authors.

Figure 6.8a: Automation curves on the command tape, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, département de l’Audiovisuel, fonds Xenakis, DONAUD0602_000613. Diagram by the authors.

Figure 6.8b: Iannis Xenakis, Polytope de Cluny, sound trajectories, 1972, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 22-2, pp. 1f. Montage by the authors.

Figure 6.9: Description of the control software by Robert Dupuy, Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 22-3, detail pp. 172f.