How to cite

How to cite

Outline

Outline

1 The concept of field as a structural approach for analyzing cultural production

2 The historical development of the artistic field: the antagonistic structure of art and money

3 A general model of the structure of the field of cultural production

4 Acting in the artistic field: Bourdieu’s view of practice

5 Changes in the field of cultural production: struggles, conversions and the dialectic of distinction

6 Critique of Bourdieu’s field theory

Pierre Bourdieu (1930–2002) was born in southwest France into a lower middle-class family. After finishing secondary school, he gained a place at the École Normale Supérieure, one of the elite universities in Paris, to study philosophy. During the 1950s, the French intellectual scene was characterized by a confrontation between proponents of structuralism (the assumption of social determination through structures) and proponents of existentialism (the assumption of the possibility of free action) (see Bourdieu and Passeron 1967). Bourdieu’s theoretical development opposed these two positions. He aimed at overcoming the opposition between determination and freedom, objectivism (the idea that objective structures shape individual action) and phenomenological or psychological subjectivism (the notion that subjective forces drive individual action). As a result of his profound critique of speculative thinking, soon after graduating with a degree in philosophy, Bourdieu moved to the social sciences. Yet in most of his works he continually returned to the philosophical and epistemological aspects of his research topics. This is one of the reasons why his work attracts the interest of scholars from many different academic disciplines, notably philosophers (e.g., Shusterman 1999; Schatzki 1997, 2018).

In the development of his social thought, Bourdieu found in the works of Karl Marx, Émile Durkheim, Norbert Elias and above all Max Weber many ideas and theoretical concepts that inspired him to build his own social theory, with some of the major elements being the view of society as a complex configuration of social positions, resources and dispositions; a profoundly historical understanding of social development; the concept of domination and the reproduction of domination; the idea that power and capital are relational social resources; the correlation between social position and beliefs; the idea that meaning-giving is socially prestructured by a shared symbolic order and social practices; and the idea of the internal differentiation of modern societies. We consider his merit to be the development of a comprehensive social theory with significant political implications. In this chapter, we will focus on his analysis of cultural production.

In his oeuvre, Pierre Bourdieu rarely dealt directly with organizational entities as such. Instead he focuses on the societal level, and we therefore view his approach to arts and culture as a rather macrosociological one. His major publication on this topic, Distinction (1984 [1979]), focuses primarily on Parisian cultural life and analyzes the social formation of aesthetic taste, cultural consumption and the social uses of aesthetic judgment as a marker of social position and belonging, in other words, as a means for social distinction. In his later works, above all in The Rules of Art (1996 [1992]), he focuses on the social organization of arts production and its historical development as a distinct and differentiated social field. In this particular book, Bourdieu investigates the field of 19th-century French literature, its internal structure and transformation. Other art forms, for example, painting, music, film and photography, are more or less touched upon and are used to explain his model of a fragmented artistic field structured by various artistic genres that are associated with different levels of legitimacy and public appreciation (see Bourdieu 1979; 1989).

1 The concept of field as a structural approach for analyzing cultural production

Bourdieu used the term field already in the 1960s (e.g., Bourdieu 1971a; 1971b [1966]), but first explained it more extensively in The Field of Cultural Production (1993 [1983]), An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology (with Loic Wacquant, 1992), The Rules of Art (1996 [1992]) and his essay Le Champ Économique (1997a). The term field had first been introduced in sociology by Kurt Lewin (1951 [1942], 62), “to describe a situation ‘objectively,’ [and this] means to describe the situation as a totality of those facts and of only those facts that make up the field of the individual.” The description and analysis of a social field is conditional on the presupposition “that there exists something like properties of the field as a whole, and that even macroscopic situations, covering hours or years, can be seen under certain circumstances as a unit” (1951, 63). Bourdieu (1971b, 161) clarifies his own specific concept of field with the analogy of being “like a magnetic field, made up of a system of power lines” and the metaphor of a “battlefield” (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992, 17). For him, field analysis aims at revealing social relations structured by different social positions together with possessions of various forms of capital and practical dispositions. Consequently, he defines his concept of field as follows:

The field is a network of objective relations (of domination or subordination, of complementarity or antagonism, etc.) between positions…. Each position is objectively defined by its objective relationship with other positions.… All positions depend in their very existence, and in the determinations they impose, on their occupants, on their actual and potential situation in the structure of the field – that is to say, in the structure and distribution of those kinds of capital (or of power) whose possession governs the obtaining of specific profits (such as literary prestige) put into play in the field. (Bourdieu 1996, 231; see Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992, 94–115)

In Bourdieu’s conception of the artistic field, the idea of artistic singularity, individuality and geniality is nothing but a myth and a (self-)promoting assertion. Artists are a priori embedded in an artistic field and therefore their artistic work is framed by the particular properties and dynamics of the (sub)field. Consequently, “the producer of the value of the work of art is not the artist but the field of production as a universe of belief which produces the value of the work of art as a fetish by producing the belief in the creative power of the artist” (Bourdieu 1996, 229). Furthermore, as a part of a broader social field, all artists are involved in, or at least affected by, social struggles as they strive to promote and advance their own artistic production, their cultural values and individual interests. Consequently, the social organization of artistic production is not the result of individual subjectivities and actions but of power relations, field positions and strategies. The sociology of arts as practiced by Bourdieu in The Rules of Art (1996) consists of a combination of a sociohistorical analysis of the development and internal differentiation of the field of cultural production and its relevant institutions, the establishment of shared convictions and evaluative criteria within the subfields, and an analysis of the social, material and cultural conditions of production, dissemination, reception and valuation of cultural goods. Overall, Bourdieu draws a relational model of social processes. While others prefer to speak of sectors, networks, art worlds or systems, Bourdieu uses the metaphor of field to highlight particular relations and mechanisms fed by power forces and struggles that determine the social inclusion or exclusion of actors (individuals and groups), their behavior and relationships to each other, the extent of the field and the degree of artistic autonomy “as if of a well-regulated ballet” (1996, 113).

2 The historical development of the artistic field: the antagonistic structure of art and money

Pierre Bourdieu took from Karl Marx the idea of a historical development of social structures as a way to understand certain trajectories, collective actions and beliefs as temporal social phenomena. In The Rules of Arts, Bourdieu (1996) investigates the transformation of the French literary field in the second half of the 19th century; he analyzes the emergence of the antagonistic structure of art, money and politics, and of a state of relative autonomy1 for certain parts of cultural production. The French literary field at that time was going through a profound internal differentiation and transformation that led to a strengthening of its autonomy. An indication of this autonomy is the separation of artistic success from commercial success. Consequently, art and commerce became at least on a discursive level binary opposites (1996, 71ff., 121ff.).

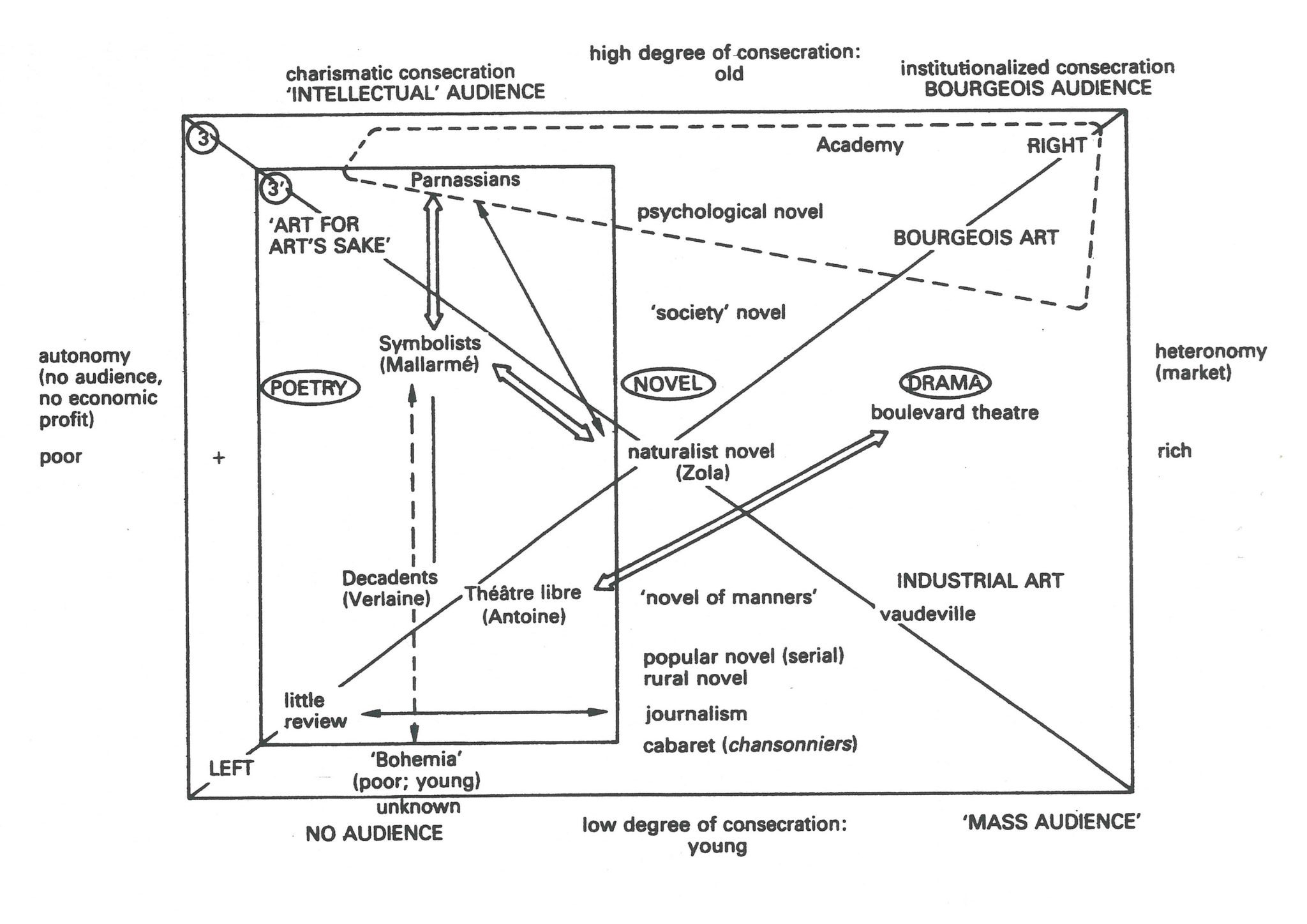

By the mid-19th century, certain kinds of French theater literature were economically very profitable, and a small number of authors made considerable amounts of money. In contrast, poetry was the least well remunerated genre, and consequently poets received few if any financial benefits for their work (see figure 2 below). Bourdieu highlights the contradicting logics of aesthetic and economic valuation, as well as the tension between the demands of a growing mass public and certain groups of artists who refused to fulfill commercial expectations and instead attempted to retain their autonomy and dedication to purely artistic goals. Yet Bourdieu is not a thinker in the romantic tradition or an essentialist who advocates a superordinate and idealistic concept of art. He describes these tensions while acknowledging that the demonstrative rejection of commerce and profit by certain groups of artists could also be understood as a strategic action either for self-marketing or to advance their own hierarchical distinctions in the literary field. Surely, the high artistic reputation of poetry was inherited from the French romantic tradition and retained its prestige until the end of the 19th century. Poetry was read by well-educated people, and although there was only a small market for this art form, a few stars like Baudelaire (1821–1867) were successful in attracting many young and ambitious authors to this field. The self-distancing of poets from others was important to create distinction and visibility. On the bottom rung of aesthetic reputation was writing for the theater, especially the comédie-vaudeville or the litérature industrielle (a term coined by Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve around 1839). Commercially successful authors of this genre were not interested in distinguishing themselves from poets, not only because they were not competing with them, but also because they were in a position to fulfill their ambitions by selling their plays to theaters. Therefore, the strategy of distancing and polemic rhetoric was one-sided. Bourdieu does not speak of poetry and comédie-vaudeville as ideal types, but we believe that this Weberian term might be appropriate here since the empirical reality is more complex and encompasses mixed types.

In between these two poles – the writing of popular theater plays and that of technically complex poetry – were the novelists. The artistic reputation of novelists varied. On the one hand, there were the novels of Stendhal (1783–1842), Balzac (1799–1850) or Flaubert (1821–1880), which as a literary production were demanding and strengthened the symbolic status of novels as a sophisticated genre. On the other hand, there were novels that were easy to read, the so-called feuilleton novels published serially in journals; their authors and publishers paid more attention to the texts’ commercial value and meeting the tastes of a broad audience.

Bourdieu generalizes his findings in a model structured by two prototypical principles of differentiation. On one side, there is a kind of commercially oriented art or l’art industriel. Monetary profits are related to the length of the production cycle, the quantity of consumers and the duration of the sales. In a few cases, commercially oriented cultural production can also gain symbolic (but not aesthetic) value when high entrance fees for attending a theater or a concert creates exclusivity for members of the upper classes. The number and, in particular, the social status of fellow consumers is therefore a relevant factor in pricing, as well as in attributing symbolic value to a particular cultural product. On the other side, there is a countermovement that claimed artistic autonomy from the influence of other social forces and developed as a specific subfield with a particular internal logic. Since this subfield sharply distinguishes itself from other fields of cultural production, it produces exclusion. Consequently, the internal recognition of an artwork increases when the audience is exclusive and aesthetically competent. Yet if an avant-garde production is accessed by a broader audience, it risks aesthetic devaluation and the artists risk becoming discredited in their artistic field because of their economic success. Therefore, as the social dispersion and breadth of audience increases, cultural credit and aesthetic status decreases. Moreover, as Bourdieu (1996, 116) points out, these aesthetic and cultural hierarchies also reflect the social hierarchies of a respective audience (see figure 2 below). The idea of cultural hierarchy – Bourdieu also uses the term taxonomy – had already been expressed in Distinctions (1984).

Further antagonism: the conflict between l’art pour l’art and l’art engagé

Bourdieu analyzes not only the tensions between commercially oriented and artistically oriented authors, but also other tensions within the literary field during the 1880s. His sociological interest in these conflicts relates to his interpretation of a field as a battlefield (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992, 17). In his view, social battles are not only unavoidable, but the motor of social transformation.2 Thus, in the Rules of Art he investigates the conflict between naturalism (e.g., Émile Zola) and symbolism (e.g., Stéphane Mallarmé). This conflict emerged from different aesthetic positions and value judgments, but also from different ideas and aesthetics about the role of literature in society. According to Bourdieu’s analysis, by the end of the 19th century in France there were two independent, but hierarchically ordered principles of differentiation in this literary field.

-

One differentiation is between elite production with a strong consecration,3 targeted at an autonomous expert audience (art for art’s sake on the top left side of figure 2) and commercial production with weak specific consecration, targeted at a heteronomous mass audience (industrial art on the lower right side of figure 2).

-

The other kind of differentiation is between an older generation of producers and audiences with a general high reputation (bourgeois art on the upper right side of figure 2) and a younger generation of producers with a general low reputation (bohemians on the lower left side). This generational conflict is extended between the bohemian and the established avant-garde (e.g., symbolists and parnassians in the left box of figure 2) and has a commercial dimension since young producers with almost no audience tend to regard those with larger audiences as adapted to the mainstream and thus corrupted.

The naturalists were outside of the field of art for art’s sake because they were following a different aspiration. Their aim was to use literature to stimulate social reform. They thus criticized the idea of art for art’s sake in favor of a socially engaged art driven by ethics and political commitments. To be clear, the structure of the conflict between the avant-garde théatre de l’oeuvre (e.g., Felix Feneon, Louis Malaquin or Camille Mauclair, see Bourdieu 1996, 367 fn. 4) and the commercial théatre de boulevard (e.g., Charles Monselet and Eugene Scribe; see Bourdieu 1996, 97 and 363 fn. 93) differs clearly from the conflict between symbolists and naturalists (see 1996, 60ff., 117ff.).

Figure 2 The French Literary Field in the Second Half of 19th Century (cited in Bourdieu 1993 [1983], 49; see Bourdieu 1996, 122).

The former reflects the relationship between art and commerce, whereas the latter is ideological and refers to the role of arts in society and the relationship between the aesthetic and the political commitment of artists. Furthermore, the respective actors involved in the different conflicts occupied different social positions and were using different strategies to legitimize their production and, to some degree, were appealing to different audiences. It is thus possible to find structural similarities between different conflicts, as Bourdieu does, or elaborate their internal differences.

In poetry (see the left subfield of figure 2) Bourdieu further distinguishes between a younger bohemian and informal avant-garde with a lower degree of consecration (lower part of this subfield), and an older academic and formal avant-garde with a higher degree of consecration (upper part of this subfield). Both literary avant-garde groups have high degrees of cultural capital and low degrees of economic capital, but because they are interesting to different audiences and employ different generations of artists, they have different degrees of consecration (see also figure 3 below). This juxtaposition is not fixed over time; after a few years, writers of a younger generation who prefer something new and original to the old and outdated, appear again on the literary stage and renounce the old style of the now older generation by compromising the dominant order, usually with the argument that older art has allowed itself to be corrupted by economic success. These kinds of field dynamics can be found in many subfields of literature – Gisèle Sapiro (2004) further develops Bourdieu’s analysis of the French literary field up to the 1970s to discuss the internal differentiation, transformation and fragmentation of the field. This fragmentation comes with a delusion of innovation and a conflicted understanding of the role of literature that leads to new splits fueled by self-proclaimed leaders. The rapid and ever faster succession of such cultural distinctions, however, made the subgroups increasingly weaker in terms of status. A further effect of this fragmentation of the literary field is the stabilization of the commercially affine practices of cultural production.

3 A general model of the structure of the field of cultural production

Bourdieu’s analysis reveals similar divisions characterizing contemporary artistic fields (see Buchholz 2015; Prinz and Wuggenig 2012; Zahner 2006). However, such internal divisions and antagonisms are never carved in stone; over time they are dynamic, and internal divisions weaken and transform the structural antagonism in the artistic field.

Figure 3 The Field of Cultural Production Embedded in the Field of Power and in Social Space (cited in Bourdieu 1996, 124).

Subsequently, adversaries may approach each other and the contrast between distinct subgenres becomes less relevant compared to the contrast between the two poles of symbolic and economic interests. The difference between the pole of pure artistic production and the pole of mass production, subjected to the expectations of the general public, then becomes less important (see examples of the New Yorker avant-garde development in Crane 1987).

Bourdieu draws a general model of the French field of cultural production, which consists of the subfield of small-scale production and the subfield of large-scale production, both of which are embedded in a broader field of power and social space (see figure 3).

This differentiation may temporarily increase and change – for the late 19th century, Bourdieu identifies two further fields in the subfield of small-scale production: first, the bohemian or experimental avant-garde art, and second, the already consecrated and established avant-garde art. On the right side of this upper left corner, we find the subfield of cultural production called large-scale production. Here cultural products are adjusted to economic interests or the enticements of potential profits. The conflicts between actors from these different subfields are structural. The struggle is for visibility, appreciation, legitimization and domination. The history of arts and art criticism reflect to some degree the outcomes of these struggles.

The inner subfield of small-scale cultural production has a high degree of autonomy, a high degree of specific (artistic) symbolic capital and a low degree of economic capital. The demonstrative rejection of the economy and the emphasis on purely artistic production are both structuring principles of this subfield (Bourdieu 1996, 81ff.). Here the lower inner field of the bohemian and avant-garde art has a lesser degree of specific symbolic capital, whereas the higher inner subfield of consecrated avant-garde has a greater degree of specific symbolic capital. Compared to the avant-garde culture, large-scale cultural production, or mass culture, has lower degrees of autonomy (and consequently higher degrees of heteronomy, that is, commercial dependencies from the adjacent power field) and lower specific symbolic capital (less artistic status or prestige but higher degrees of commercialization and economic capital).4

The field of power on the upper right corner of figure 3 consists of people and institutions that have considerable social and economic but also cultural capital. The rest of society is located in the lower box of the (national) social space. Here, distant from the field of the so-called high arts, we find people with low cultural and economic capital who are not particularly interested in these kinds of arts and instead consume popular culture or are engaged in other cultural activities that take place within their social class.5 This last point is also underlined by scholars from British Cultural Studies (e.g., Munt 2000).

Bourdieu acknowledges certain social dynamics. The artistic subfield of small-scale production is constantly trying to maintain autonomy, keeping the surrounding economic and political powers at bay. It thus tries to maintain its control by generating its own high levels of strong currencies, that is, artistic appreciation and reputation, which are kinds of symbolic capital in some territories of the field, as indicated by the plus sign in figure 3.

Near the artistic field’s plus signs, market forces do not impact significantly on the subfield of small-scale production as there is no realistic expectation of attracting large audiences and generating economic profit. Here only the criteria of consecration are relevant and shape artists’ endeavors (Bourdieu 1993 [1983], 38). The more autonomous an artistic subfield is, the less the laws of the surrounding field of power determine its inner hierarchical structure and the more powerfully the actors in this subfield can maintain their field-internal power. In the case of the subfield of small-scale production, which enjoys autonomy to a great extent, the audience is small and consists mainly of other producers or peers from the same subfield (e.g., in contemporary poetry). The inherent logic of this artistic practice is systematically inverse to the logic of markets, because here the loser takes all (Bourdieu 1996, 21, see also 114f., 141ff.).

However, the artistic field also has subfields with low levels of its currency (artistic appreciation and reputation), wherein artistic production can be dominated by the strong forces of the surrounding power field. Such structural relationships, Bourdieu emphasizes, are characterized by commercialization as a main factor threatening artistic autonomy. The power field influences artistic subfields not only economically (Bourdieu 1993 [1983], 40) as it can also promote developments by rewarding artists, funding arts organizations, promoting visibility and disseminating a particular kind of artistic production. Agents from the power field can also try to impede certain developments by refusing to grant them funding or even by censorship and repression – think, for instance, of the situation for film makers in the United States during McCarthyism in the 1950s (see Couvares 2006) or of literary writers in the communist countries (see Ermolaev 1997). Yet it is worth noting that the power field is homogeneous and in certain situations is fragmented by inner struggles, for example, between the old and the new bourgeoisie, and between the old political caste and new highly educated experts from the universities (e.g., in France in the 1980s). Therefore, the artistic field is not only influenced by the market but also by political ideologies. Yet power evokes counterpower and actors are generally able to act strategically (see Bourdieu 1990a [1980], 53ff.). From this perspective, Bourdieu ascribes resilience to the artistic field, since otherwise it would have disappeared and completely merged into the power field (Bourdieu and Haacke 1995).

When referring to field actors we should think not only of artists. Bourdieu (1996, 229) distinguishes between the actual art producers (e.g., writers, painters, musicians) and art distributors or intermediaries (e.g., art dealers, publishers, curators, museum and festival directors, critics, art theorists and academic scholars, but also art organizations as collective actors), who play a pivotal role in the formation of artistic and economic success. Many cultural intermediaries hold a hybrid position. On the one hand, they must know and apply market principles to the autonomous artistic field; on the other, they must know and appreciate the values and qualities of art producers so as to be able to act in their in-between position and not lose their special sense for the art producers or the consumers.6 In many ways, these intermediaries must emulate the lifestyles of their fellow artists in order to gain and maintain their trust. In this sense, they are “merchants in the temple” (Bourdieu 1993 [1983], 40), since they have to trick art producers by showing no particular interest in economic or political advantages, although they most definitely have these interests. The rejection of the economically dominated field of power extends so far that one must appear to express one’s disinterest in economic and political issues. However, this normative expectation does not mean that economic interests are not latently effective. They express themselves in such a way that the artist behaves economically as a gambler, taking great economic risks without hesitation and having little or no income over a longer period, although hoping that at some point there will also be an economic breakthrough (see Abbing 2002; Heinich 2000a).

4 Acting in the artistic field: Bourdieu’s view of practice

According to Bourdieu (1998 [1994]), all human activities are conditioned by their social environment and the actors’ relational positions in the various social fields. Additionally, Bourdieu ascribes people the capacity to act intelligently in order to reinforce their positions and their gains (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992, 98f.). Acting in the artistic field, and in arts organizations, implies antagonism, but also coalition and cooperation. Such dynamics are formed along structural parameters, such as power relations, resources and rules, which nevertheless do not exert a determining force in the strictest sense (Bourdieu 1996, 234ff.). When analyzing the actor relations in various historical situations, Bourdieu often speaks of “strategies” that are not the results of calculation and rational reasoning – although they may involve reflexive moments – but of a “feel for the game” (Bourdieu 1990a [1980], 66f.; Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992, 128). “The most effective strategies are those which, being the product of dispositions shaped by the immediate necessity of the field, tend to adjust themselves spontaneously to that necessity, without express intention or calculation,” as Bourdieu (2000, 138) puts it. Consequently, having a feel for the game enables intelligent action. Consciousness, intentionality and reflexivity may play a role, although the feel for the game is indispensable, since the cognizant actor “exactly knows what he has to do … without needing to know what he does” (Bourdieu 2002a [1984], 74; our translation). Intelligent action goes hand in hand with knowing the mostly unspoken hierarchies and evaluative logics, the relevant cooperative bundles (e.g., artistic groups) and interdependencies in a certain field, but also intuitively anticipating actions by co-actors and opponents and knowing how to effectively achieve something. In other words, le sens du jeu (the feel for the game) and le sens pratique (the practical sense) presuppose familiarity with a particular social field.

People enter and play the game of the artistic field if, and only if, they believe that it is worthwhile doing so – for example, in following its rules, getting involved in antagonistic relations, investing time and energy in improving their position, etc. “The collective belief in the game (illusio) and in the sacred value of its stakes is simultaneously the precondition and the product of the very functioning of the game.” (Bourdieu 1996, 230) This belief is less theoretical and more practical, as it is constituted and confirmed by “innumerable acts of credit which are exchanged among all the agents engaged in the artistic field.” Consecrated artists promote younger ones and in return the latter create masters and schools.7 Artists acknowledge the aesthetic sensibility of their collectors, and collectors – not entirely altruistically – promote the visibility of their artists. Curators and critics remain loyal to certain artists, and receive an image transfer from the successful ones whom they have discovered and championed, and so forth.

The practical sense of the agents is socially constituted. Here Bourdieu’s concept of habitus plays an important role (Bourdieu 1990a [1980], 52ff.). Habitus is not understood as a causal force, but rather as a system of actionable dispositions that are socially constituted and practically acquired (Bourdieu 1990a [1980]; Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992, 98). Habitus is personal because it is developed through the particular experience of the agent (see also the concept of personal knowledge in Polanyi 1958). It is “the social embodied” (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992, 127) and has a “socialized subjectivity” (Bourdieu 2005, 211) because it results from an agent’s socialization, and it has familiarity with a particular field of practice and to a particular agent’s position in this field. With the concept of habitus and of practical sense, Bourdieu overcomes, first, the classical theories of action, that is, the idea that conscious and rational decision (1998, 92–123)8 or that intentional will (1990a [1980], 43–51; 1998, 97f.) cause action and, second, the opposition between structuralist and agential theories.

As a central concept in his social theory, habitus is the site of a complex interplay of mediations between macrosociological conditions and concrete situations at the microlevel. Mediations guarantee stability, but also social changes – something that Bourdieu gives more emphasis on in his later works:

Habitus goes hand in glove with vagueness and indeterminacy. As a generative spontaneity which asserts itself with an improvised confrontation with ever renewed situations, it obeys a practical inexact, fuzzy sort of logic, which defines one’s normal relation to the world. (Bourdieu 1990b [1987], 77f.)

Moreover, the concept of habitus is associated with what Bourdieu calls “homology”9 between the objective position of an individual in a given field and their positioning, or more generally between existing class structures and objective conditions in artistic fields, and elicit a range of aesthetic possibilities (including aesthetic taste) in line with one’s class-bound disposition (see Bourdieu 1984, 230ff.; 1990a, 55ff.; 1996, 86ff., 141ff., 161ff.).

5 Changes in the field of cultural production: struggles, conversions and the dialectic of distinction

Membership in the field of cultural production is not strictly regulated since the boundaries of the field are permeable. In order to become an artist, one does not necessarily need a high cultural or educational background or any economic capital – though the possession of any form of capital can be advantageous. That is why artists are so diverse and barely organized in lobbying associations or unions (Bourdieu 1993 [1983], 43).

From Bourdieu’s perspective, struggles among different social fractions occur due to conflicting interests, pretensions and divisions. Such struggles continuously reshape the field of cultural production and the relationship between the primarily economically determined, and the mostly artistically determined, subfields. Notably, struggles are unavoidable and never-ending, since every status, position, reputation and value in the field are relative and volatile. Bourdieu refers, for instance, to the structural antagonism between the young and the old, the established and the new or in Bourdieu’s terms “orthodox” versus “heterodox” positions. When some artists become consecrated, they start to dominate their artistic field and “make gradual inroads into the market, becoming more and more … acceptable the more everyday they seem as a result of a more or less lengthy process of familiarization” (Bourdieu 1996, 159). Therefore, even highly autonomous artists fall, so to speak, victim to heteronomization when they become successful. In addition, there is a crowding-out effect: each new artistic act that occurs in the field can potentially displace or delegitimize a previous artistic act, at least in the subfield of bohemian avant-garde. This old art will then either wither or shift to the established avant-garde, and then to the commercial field of mass culture (if this art is very successful or is disposed to professional distribution and marketing services). Bourdieu (1996, 159) thereby brings the time dimension into his analysis of change. He understands the new as a fleeting phenomenon soon to be replaced by another new, and pushed into an archival or museum-like artistic valorization (a valorization that then translates into greater economic success): “The field of the present is merely another name for the field of the struggle …. Contemporaneity as presence in the same present only exists in practice in the struggle that synchronizes discordant times or, rather, agents and institutions separated by time and in relation to time” (1996, 158).

Internal struggles may lead to a change of positions within an existing field. However, such struggles do not necessarily cause a complete upheaval of the cultural hierarchies and field structures. Bourdieu (1996, 127f.) basically argues that any substantial transformation of the field of cultural production, or of its various subfields, requires the effective support of external forces that occur outside the field. He mentions, for instance, the growth of audiences’ education and the expansion of cultural markets. And he adds: “Although largely independent of them in principle, the internal struggles always depend, in outcome, on the correspondence that they maintain with the external struggles – whether struggles at the core of the field of power or at the core of the social field as a whole” (1996, 127). External forces can be derived from major socioeconomic upheavals, for example, a transformation of the political system that leads either toward a more liberal or a more paternalistic and oppressive control of cultural public life, or a long military conflict with strong societal, economic and demographic changes. Therefore, internal cultural struggles depend on the extent to which they can establish a link to field-external conflicts; or, to put it in the terminology of Bourdieu’s model, the field of cultural production, the field of power and social space are vessels communicating notably in both directions. Bourdieu’s (1996, 117–128) example for this is the emergence of literary naturalism around Émile Zola and his companions in the 1860s, and the subsequent crisis of naturalism and the renewal of an idealism and mysticism among the bourgeoisie in the 1880s. Bourdieu associates these changes with the economic and political changes in those decades (1996, 128–131). Another example that Bourdieu uses to demonstrate the simultaneous influence of field-internal and field-external forces is the invention of the intellectual as a public figure in France. In the second half of the 19th century, publicly recognized intellectual authors received a more general as well as a certain political authority, which emerged from the social autonomy of the literary field.10 One of the first public intellectuals in France was Émile Zola. Bourdieu references Zola’s open letter (published in the newspaper L’Aurore on 13 January 1898 and addressed to the President of the French Republic), in which Zola took a clear position on the Dreyfus affair. Bourdieu analyzes how Zola conceived of himself as someone with “a mission of prophetic subversion” (1996, 129) who was intellectually and politically capable of acting as an aesthetical, ethical and political authority.11 “The intellectual is constituted as such by intervening in the political field in the name of autonomy and of the specific values of the field of cultural production which has attained a high degree of independence with respect of various powers” (1996, 129; emphasis in the original). Zola’s intervention in the field of politics does not presuppose autonomy of the intellectual field; it constituted and confirmed this autonomy. Bourdieu concentrates primarily on the field of literary writers, but he sketches a similar dynamic for the field of visual artists (1996, 131ff.). Here he refers to the symbolic revolution of Édouard Manet and other impressionists against the Parisian Academy of Fine Arts (see Salon des Refusés, 1863 and later Salon des Indépendants, 1884), which stood for the autonomization of the field of visual artists (see Bourdieu 2017).12

In the second half of the 19th century, the increased power of the petty bourgeoisie is also reflected in artistic and institutional changes in the field of cultural production, that is, certain organizations that are related to the consumer preferences of the petty bourgeoisie. In this case, the most heteronomous cultural producers could not resist (and some of them did not want to resist) external demands from this group. They adapted to the interests of the ruling social class and to the class of the petty bourgeoisie, whereas the autonomous artists regarded these heteronomous artist colleagues as traitors in the service of the power class, and as enemies of art itself (Bourdieu 1993, 41). Avant-garde art producers, who were economically dominated but symbolically dominant in the artistic field, also had the capacity to act as mouthpieces for other dominated people in the wider field of power, and they also frequently used this potential (1996, 44).

6 Critique of Bourdieu’s field theory

Before referring to some critical objections, let us recapitulate what Bourdieu has to offer the sociological and humanistic study of arts. First, by elaborating the concept of relative autonomy he overcame idealistic and Marxist views of arts that had dominated until the 1960s (see Heinich 2018, 183–186). Second, his concepts of domination and struggle for legitimacy gave a political meaning to artistic discourses and developments. Third, to our knowledge, Bourdieu was one of the first sociologists of the arts who combined qualitative and quantitative methods in his research.

Nevertheless, Bourdieu’s oeuvre goes far beyond the scope of a sociology of arts. And, unsurprisingly, his readers saw many different Bourdieus in different phases and focuses of his long-standing scholarly works – some saw a structuralist, others a praxeologist, a pragmatist or a philosophically inclined and a politically engaged Bourdieu. Consequently, criticism is related to different readings of his works, one of which concerns the dominant position of Bourdieu’s ideas in sociology. Since Bourdieu positioned himself as a critic of the social inequalities reinforced by art and culture, as well as an opponent of the neoliberal economization of society, some scholars disapprove of his seemingly political or materialist and critical understanding of his research topics. Neither did Bourdieu refrain from criticizing other sociological positions, so it is therefore not surprising that he had his own detractors.

We will now summarize a number of critical perspectives, primarily related to Bourdieu’s theory of artistic fields. One frequent accusation refers to his latent structural determinism (see, e.g., Born 2010; Prior 2011), evidenced by his emphasis on the structuring effects of the field. Moreover, it is worth noting that Bourdieu’s metaphors – for instance, terms from classical mechanics, such as “force” – seemingly equate societal dynamics and laws in physics (for a critical comment, see Becker 2006). On the contrary, scholars from a phenomenological or an interactionist perspective generally ascribe actors a higher level of agency. Yet these critiques have disregarded the fact that, from the late 1980s onwards, Bourdieu explicitly rejected deterministic views (see, e.g., Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992, 135f.) and insisted on the generative capacity of habitus (Bourdieu 1990a, 55; Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992, 122).

A further critique of Bourdieu’s sociology of arts has been his neglect of artworks, and particularly questions of artistic form, style and content (see Becker 2006; Born 2010; De La Fuente 2007). It is clear that Bourdieu tends to conceive of aesthetics as an ideological discourse in a process of positioning and legitimizing a particular art form and fails to investigate how artworks affect people (see DeNora 2000; Hennion 2015 [1993]). There is also an absence in Bourdieu’s oeuvre of any comments on youth culture and popular rock and roll music, which has had a tremendous effect on the various social fields of our societies. This neglect of artistic materiality, form and style goes along with a neglect of investigating the effects of technology on the structuration and transformation of the field of cultural production. Bourdieu’s focus lies primarily on structural antagonism, internal conflicts, as well as on the historical process of autonomization.

In this chapter we have not discussed Bourdieu’s analysis of the social formation of taste. While Bourdieu (1984, 20, 123, 175ff.) speaks of a close correlation and homology between taste and social class, other researchers emphasize the hybridization and eclectic aspects of taste and therefore argue for a looser relationship between class and taste (e.g., Hazir and Warde 2016; Peterson and Kern 1996). This is probably a less deep-rooted critique, since different empirical studies often apply different methods, generate different data and refer to different social spaces. Nevertheless, the contingency of empirical findings can be seen as an argument against a generalization of Bourdieu’s homology thesis.

It is worthwhile examining whether Bourdieu’s analysis of the field of cultural production is still empirically valid. Intuitively one may assume that the structuration of the artistic field in late 19th century France differs from the structural conditions of contemporary artistic fields in other countries. From the 1930s onward the field of film production, from the 1950s the field of popular music and from the 1960s the field of visual arts, all went through a rapid globalization and market expansion, prompting many sociological scholars to speak of a “profound transformation” (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005), a “liquefaction of social structures” (Bauman 2000) or a “paradigm shift” (Heinich 2014). With explicit reference to Bourdieu, Nina Zahner (2006, 277ff.) refers to the “new rules” in the field of visual arts and Larissa Buchholz (2022) to the “global rules” of this field. In the 1960s, Zahner (2006, 282) notes that artists associated with pop art refused an ostentatious demarcation from popular mass culture, yet they succeeded in gaining a high artistic reputation. Furthermore, the upper middle-class, who started buying contemporary art, were less interested in highly sophisticated, autonomous art, or perhaps less competent to appreciate its genuine value. The structural opposition between art and economy, between highbrow and lowbrow arts, as well as between autonomy and heteronomy has therefore diminished – a tendency reconfirmed when Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature (see Sapiro 2004; Bennett 2016; Abbing 2022; Kirchberg et al., 2023). But did Bourdieu ever believe that structural oppositions were permanent or universal? Most of his readers, including Zahner herself (as well as us), acknowledge that Bourdieu displays a dynamic understanding of field structures and the social organization of arts.

Buchholz’s (2022) extension of Bourdieu’s field theory from the national to the global level focuses on the newly emerged field of contemporary visual art. Globalization is evidenced by, first, the emergence of globally acting organizations (e.g., transnational art biennials, art fairs, auctions and global galleries), second, new millionaires and billionaires from non-Western countries (especially from China, Russia and the Arabian peninsula), third, digital platforms and online art rankings (e.g., artfacts.net or artprice.com) and, fourth, financial regulations that facilitate the global transfer of economic capital and reduce transaction costs (see Quemin 2006, 2021). Buchholz’s analysis revises some central concepts of Bourdieu’s work, for example, the typology of (semi-)autonomous and (semi-)heteronomous artists, and the divergent logics of the market and aesthetic evaluations. She introduces a decoupling of artistic consecration and market success that is less rigid than Bourdieu’s theoretical concept and consequently refers to the emergence of a “dual economy,” that is, new institutional structures on a global level with different temporalities and spatialities (Buchholz 2022, 111–120). The global field of contemporary visual arts in the neoliberal era of late capitalism seems to be more open and more inclusive for artists from less rich and privileged regions, compared to the national and regional fields of visual arts. Buchholz offers detailed empirical data for this argument, without ignoring the ongoing asymmetries of power and resources in the world. She comes to the positive conclusion that

a more cosmopolitan, global vision of contemporary art originated [since] noncommercial art organizations and circuits provided the necessary space for curatorial risk-taking beyond Western orthodoxies…. Instead of joining the chorus of market-centrism … this book spotlights the cross-border dynamics of institutions, artists, and their mediators that have run against the zeitgeist of financial instrumentality. (Buchholz 2022: xxi; see Buchholz 2022, 265ff.)

Her new empirical data does not necessarily challenge Bourdieu’s field theory. Buchholz does not argue against his theory, but rather she points to the structuring differences between the artistic field in France in the second half of the 19th century and the global field of visual arts in the early 21st century.

Bourdieu’s field theory is one of the most known and applied theories of the social organization of arts.13 The attraction of his approach is the intuitive understanding of organizing the arts as a competitive scheme, which fits very well into the contemporary culture of capitalism. The contentiousness of his actors in different power fields stands in stark contrast to the rather peaceful negotiability of Becker’s art worlds. A very different approach to understanding the social organization of the arts is Luhmann’s systems approach toward organizing the arts, which we will discuss in the next chapter.

Endnotes

-

The term relative autonomy, which implies only partial dependency, runs contrary to the idealistic assumption of total artistic freedom, as well as against the Marxist assumption that art is a reflection of society.↩︎

-

“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles” (Marx 1998 [1848], 35).↩︎

-

Bourdieu deliberately uses the term consecration, which derives from a theological discourse and the granting of sacred dignity to a person or a thing, to refer to the distinction between the profane and the sacred that goes back to Émile Durkheim (1995 [1912], 34f.).↩︎

-

See Kirchberg et al. (2023) for a study of politics as a heteronomic factor other than the economy.↩︎

-

Here we see the difference between two meanings of the French word culture: one a narrow and selective meaning that refers to fine arts and letters and another that has a broader anthropological meaning that refers to various signifying and symbolic activities.↩︎

-

Nathalie Heinich (1998) elaborates further on this interplay and speaks of a “triple game” between artists, intermediaries and audiences.↩︎

-

An artistic school generally consists of individuals from the same generation – except their master and hero – and have a strong aesthetic and epistemic coherence.↩︎

-

Bourdieu (1998, 92–123) explicitly criticized for instance Gary Becker’s The Economic Approach to Human Behavior (G. Becker 1976).↩︎

-

The term homology was taken from the art historian Erwin Panofsky in a critique of the reflection theory of art.↩︎

-

Sapiro (2004, 159f.) argues that from the 1970s onward there was a shift and decline of the figure of public intellectuals in France.↩︎

-

Victor Hugo represents another case of a literary author who gained a public reputation for his social and political critique.↩︎

-

This transformation also took place two decades later in other European countries and is generally known as the Secessionist Art Movement.↩︎

-

The international fame of this approach is reflected in the number of Google’s English language search results that include the terms Bourdieu and field theory (approx. 108,000 in 2024), compared to the terms Becker and art worlds (approx. 83,000 in 2024).↩︎