How to cite

How to cite

Outline

Outline

1 An introduction to Becker’s thinking

2 The condition of cooperation in the creation of art

3 Conventions as outcomes of collective actions

4 Division of labor in art worlds

5 Art worlds as a holistic approach

6 Extension of the art worlds perspective: the sociological focus on artworks

7 Critique of Becker’s art worlds

In 1982, Howard S. Becker (1928–2023) authored Art Worlds, one of the most influential books in the sociology of organizing arts. He was born in Chicago, where he grew up in a well-off, liberal middle-class family. Becker studied and graduated from the University of Chicago, home to John Dewey, George Herbert Mead, William Isaac Thomas, Ernest Watson Burgess, Robert Ezra Park, Everett Cherrington Hughes and Herbert Blumer, who directly or indirectly contributed to the establishment of the so-called Chicago School of Sociology (see Becker 1999; Plummer 2003). Without doubt, Becker belongs to this tradition, but his sociological foundations, which can be labeled as pragmatist, might not only have been influenced by his academic career. Apart from being a sociologist studying social interactions, collaborations and conventions in art worlds, he was also a jazz musician who played piano in Chicago bars – Lennie Tristano was one of his teachers and mentors (see Becker 1990, 498). His own artistic engagement offered him insights that significantly enriched his sociological understanding of arts, as the following quotation illustrates:

Maybe the years I spent playing the piano in taverns in Chicago and elsewhere led me to believe that the people who did that mundane work were as important to an understanding of art as the better-known players who produced the recognized classics of jazz. Growing up in Chicago … may have led me to think that the craftsmen who help make art works are as important as the people who conceive them…. Learning the “Chicago tradition” of sociology from Everett C. Hughes and Herbert Blumer surely led to a skepticism about conventional definitions of the objects of sociological study. (Becker 1982, ix)

Becker studied arts from a symbolic interactionist point of view, meaning he focused on the interactions of people and their negotiated outcomes. In that sense, artists and the people and organizations who support them are equally agents in their art worlds. Mutual understanding and the capacity to cooperate amid a social group (team, network, collective) have been important characteristics in all of Becker’s work for more than seventy years. Both, mutual understanding and cooperation, are possible on the basis of shared conventions.

1 An introduction to Becker’s thinking

Becker looks at social behavior from a non-normative viewpoint and approaches social phenomena from a very pragmatic perspective. For him, the core academic method of a sociologist is fieldwork, doing research in real environments, gathering data through observation and interviews and then telling stories about it. The observability of the research objects is assumed, and Becker rejects ideas of “deeper” or “hidden” structures as misleading (Becker and Pessin 2006, 285; Hughes 2015, 776). During his formative years in sociology, Becker took an equally critical stance toward purely quantitative and deductive theoretical approaches. Consequently, he has always been skeptical about abstractions and causal explanations. Instead he practices open and explorative approaches like Glaser and Strauss’s Grounded Theory (see Strauss and Corbin 1997) and has great expertise in qualitative data gathering and data analysis (see, e.g., Becker 1970).

In one of his early publications in 1953, Becker writes about “becoming a marijuana user” without once interpreting this as “deviant behavior.” The same is true for studying artistic activities. Becker (1982, 151) notes that sociologists need to not “decide who is entitled to label things art … [they] need only observe.” He deliberately avoids any aesthetic judgment concerning arts and non-arts or the artistic quality of an artwork. Similarly, from his perspective, there is no such thing as deviant artistic behavior – every artistic behavior can be accepted by at least one art world, if not several. Individuals who follow divergent artistic paths will succeed if they find other artists who will follow them and create their own art worlds together. The appreciation of any art, even the most unusual or eccentric, “stems from their being recognized by the other participants in the cooperative activities through which that world’s work are produced and consumed as the people entitled to do that” (Becker 1982, 151; see Lena 2019). Therefore, a first and basic meaning of the term art world is a “network of people whose cooperative activity, organized via their joint knowledge of conventional means of doing things, produces the kind of art works that art world is noted for” (Becker 1982, x).1 It is worth noting that Becker uses the plural term art worlds for his book published in 1982. This implies diversity among working relations, collaborations, conventions and evaluative standards as well as types of artists, or “modes of being oriented to an art world,” as Becker (1982, 371) puts it.

This conception of many coexisting fragmented art worlds also reflects his understanding of sociology as an academic discipline. Becker has always viewed powerful organizations like the American Sociological Association critically, “I’d hate to live and see the time when any organization could speak for all of sociology” (Becker 1976, 43; cited in Danko 2015, 36). This statement is relevant to an understanding of his clashes with other schools within the sociology of arts.

When Becker developed his concept of art world in the 1970s, he was departing from two distinct sources: one was the concept of social world that was derived from Alfred Schutz (1967 [1932]) and was later further expanded to become one of the basic concepts of the Chicago School of Sociology (see Strauss 1978). The second source is Arthur Danto, a philosopher who used the term artworld (in the singular), arguing that contemporary artworks are not always immediately recognized as art because they break certain basic conventions. “To see something as art requires something the eye cannot decry – an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: an artworld” (Danto 1964, 580). Becker (1982, 156) appropriated Danto’s thesis that art worlds ratify objects and performances as art. However, as Danto did not elaborate his concept of an art world any further, we view Becker’s conception as a genuine theoretical contribution. Becker (2014, 170) explicitly refers to the so-called labeling approach that he developed in Outsiders (1963, 9): “The deviant is one to whom that label has been successfully applied; deviant behavior is behavior that people so label.” Accordingly, he argues that the attribution of the label art to an object or performance means acknowledging membership in an art world. Therefore, art is something people do together; it is the outcome of collective action.

Being an artist goes along with participation in art worlds. The entitlement of creating art and the appreciation of artistic output by peers and consumers is based on consent for and acknowledgment of an activity as art. People’s actions and judgments only have a situational validity since, as Becker insists, there are many different art worlds. Each one is based on the consensus of at least a few people who cooperate to realize concrete projects on the basis of specific conventions and shared identities. Cooperation is a keyword. Becker also speaks of “joint action” (1974, 767) and “collective activities” (1982, 1), and states that “collective actions and the events they produce are the basic unit of sociological analysis” (1982, 370; see Blumer’s 1986 [1969], 16–20 analysis of joint action).

A second and broader meaning of art worlds is the social, institutional and material sites of artistic production. Becker does not make this explicit – perhaps because he primarily focuses on interacting networks. Yet the chapters in his book Art Worlds include markets, cultural policies, funding structures and art criticism as parts of art worlds, thereby suggesting this broader aggregated meaning. In the last pages of his book, Becker emphasizes the importance of “a general approach to the analysis of social organization [of arts]” (Becker 1982, 369). From this perspective, Becker regards himself as an “unwilling organizational theorist” (Becker, quoted in Hughes 2015, 770).

2 The condition of cooperation in the creation of art

Howard Becker begins Art Worlds (1982) in a way that clearly identifies him as a representative of Symbolic Interactionism. This sociological paradigm emphasizes that an individual is the product of a cooperative community while the community is the product of many interacting individuals who consent on certain issues. Their reciprocal cooperation enables agreement on assignment, appreciation and evaluation of certain objects and activities. From this perspective, ascriptions like, This is an artwork, or judgments like, This is a good work are not subjective, but rather intersubjective cooperative outcomes (see Farrell 2001).

The central concepts of collective action (Becker 1974) and collective activity (Becker 1982) address the social division of labor, the problem of social coordination and the interrelationship of different actions. Wider forms of social action emerge when actions by various participants with different motives and competences are interlinked. Thus, Becker defines art as the result of collective action by participants of art worlds. He refers not only to the creative process, but also to all activities, including production, editing, publication, marketing, distribution, evaluation, reception, archiving and the preservation of artistic work. Interactions within these collective activities constitute the focus of Becker’s analysis.

Becker (2006) illustrates collective activities in music as constructive cooperation that includes negotiating conventions in the process of making music from the first notes to public performance. Indeed, the whole process from composing, finishing the musical score to rehearsals and performance of a piece of music at a concert hall is a complex process that includes myriad social interactions and cooperation at several levels. To be more precise, music presupposes a musical tradition since there is no musical practice from nothing. People need to invent, build and maintain musical instruments, and also to train others how to use them. In literary cultures musicians have invented and continue to invent elaborate musical notations (while in nonliterary cultures music is passed on orally). Music must be composed, properly noted, copied and distributed – and musicians must learn this notation and practice the musical performance. Rehearsals depend on the provision of finances, appropriate venues, times and technological means. Marketing and advertising must be targeted at an audience with certain cultural interests and competences in receiving and appreciating this kind of music, and concert tickets must be sold. These preconditions can be applied, with variations, to almost all arts. Evidently, many different people are needed, people who have a creative idea, people who can help realize the creative idea (as music, a film, a book, a dance or any other medium); people who facilitate artistic practice (producers of artistic materials and instruments, technicians, workers), people who facilitate financing and distribution (agents, legal advisers, managers, accounting personnel, advertising people), people who elaborate the symbolic value of artworks (journalists, critics, academic scholars) and finally an audience, which is ideally competent at creative interpretation, aesthetic appreciation and discussion. Wide cultural interest, sources of inspiration and public deliberation presuppose sufficient financial resources, leisure time, cultural education and a politically liberal atmosphere. Although the configuration of such activities certainly varies from one art form to another, Becker’s generalized argument is simple: all of these varied activities and social conditions are necessary for arts. Arts are the outcome of collective actions (Becker 1974). The same holds true for arts organizations, which are the outcome of collective activities.

It takes many people to create cultural products, communicate them, secure audiences and facilitate the appreciation and ascription of value. Extensive participation and the complex coordination of many people in art worlds demand rules of communication and interaction. Becker uses here (with reference to David Lewis, 1969) the term conventions. Conventions are not prescribed by authorities, rather they result from practice-based coordination and negotiation, and they become widely accepted when they appear beneficial or meaningful for most practitioners.

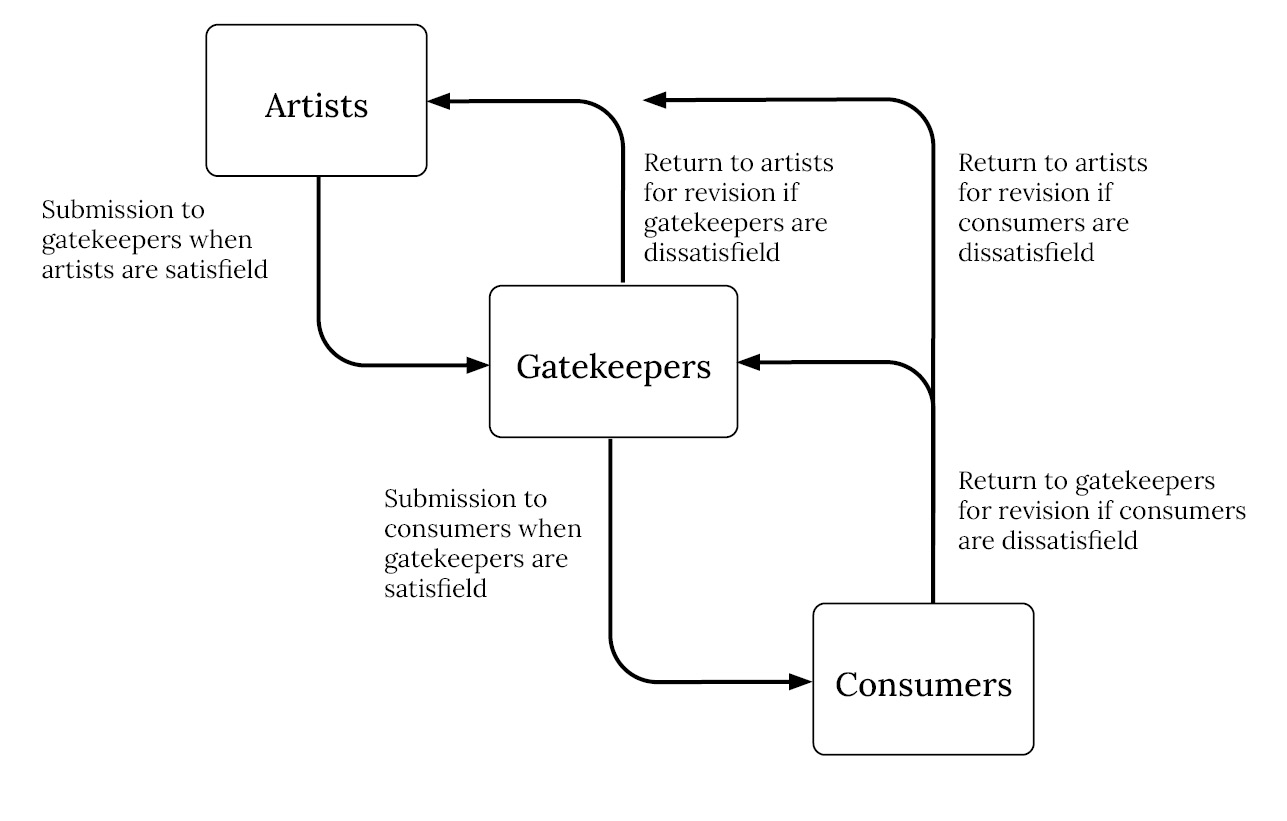

Cooperation between members of an art world is necessary in order to organize the complex projects of production, distribution and consumption of art. At all levels, there is the need for finding and stabilizing artistic and action-related criteria. The artistic evaluation is a result of interactions between the members of an art world. Think of a team of people who together produce a movie. Let us assume that they share the same artistic judgment about the movie with relevant critics and distributors. Before releasing the movie, they may sample the aesthetic judgments of consumers or their peers in the film industry. If the results are strongly negative and show that the projected audience will not appreciate the movie’s artistic value, it may be returned to the screenwriter and artistic director for improvement until the three levels of production, distribution and consumption agree on its artistic value and appropriateness (Becker 1982, 192ff.; see also figure 1 below). At all three stages, we can identify certain people who have a stronger say in the matter, so-called opinion leaders or gatekeepers who open the gate for an artwork or close it from the next step in the process of production, distribution or consumption. As a rule, gatekeepers have the power to influence careers and reputations since “judgments about what constitutes great or important art are affected by the operations of distribution systems, with all their built-in professional biases” (Becker 1986, 72). However, Becker rejects notions of determination and ascribes efficacy to the members of the art world – in other words, they have the capability to negotiate with gatekeepers and persuade them or circumvent their instructions, break agreements, and so on. Processes in art worlds remain fluid, dynamic and undoubtedly somewhat contingent.

The appreciation of an artwork can be best described as a feedback loop of different claims and objections, with the artistic and monetary value of an artwork developing in a communicative process between various actors involved. This process is takes place in relationships between art producers and art distributors, between art distributors and art consumers, and sometimes directly between art producers and art consumers.2 It is an iterative process of negotiation with the aim of enhancing the quality and increasing the value of an artwork for art producers, distributors and consumers (Becker 1982, 201). The following is our graphic interpretation of this interaction model (fig. 1).

The focus on such continuous negotiations is typical for the sociological paradigm of Symbolic Interactionism. Becker (1982, 202) notes that many artists “often take into account the way other members of the art world will react to what they decide.” Finally, artists have an accurate feeling about the reactions of others since they share the same conventions. From this perspective, Becker believes that art worlds are constituted by “well-socialized members of society” (1982, 46). Socialization implies familiarity, embodiment and routinization (1982, 203); as a result, artists “experience conventional knowledge as a resource” that enables them to make appropriate choices (1982, 204). Conventions are therefore not the rule of the most powerful, but the result of shared learning processes, shared practices and negotiations among people who participate equally in an art world.

Figure 1: Flow Chart of Interactions during the Formation of Arts. Image by the authors.

3 Conventions as outcomes of collective actions

Conventions as a sensitizing concept indicate routines, patterns of action and evaluating criteria that are taken for granted and enjoy broad acceptance in, at least, one art world. Becker (1974, 771) understands this term as “being interchangeable with such familiar sociological ideas as norm, rule, shared understanding, custom or folkway, all referring in one way or another to the ideas and understandings people hold in common and through which they effect cooperative activity.” For him, conventions fulfill practical needs by creating shared understandings, facilitating coordination, shaping expectations and reducing friction (see also Becker’s reference to Lewis, 1969, in Becker, 1982, 55).3 Furthermore, conventions are central to the organization of activities and establish regularities that evoke a certain stability – for instance to the world of classical music (Becker, 1995, 301). Although conventions correspond to “ranked statuses, [and] a stratification system” (Becker 1974, 774), they do not represent structures that determine actions. For Becker (2006, 23), people are generally free to break conventions, choose among alternative ones or reinterpret their meaning. Furthermore, conventions change as the conditions of cooperative activities change (Becker 1982, 59). Therefore, Becker’s use of conventions to explain collective action is not a structuralist one.4

The complex cooperation within art worlds and between different social worlds – that is, between artists, distributors and the audience – requires conventions.5 Such conventions are not constantly rebalanced and redefined in every production, exhibition or performance, but are based at least to a large extent on routines that were already pre-established in these contexts and are backed by institutions. Such conventions are not only customary, but also taken for granted, since many have become so familiar that they are no longer consciously adhered to.

Successful art worlds that organize the production and distribution of art are thus based on shared conventions. “Only because artist and audience share knowledge of and experience with the conventions invoked does the artwork produce an emotional effect” (Becker 1982, 30). So sometimes, a famous pop musician merely names one of their titles in a concert and the listeners react emotionally, even before the first note, and can sing along at the same time. Artists take advantage of the audience’s expectations and can sometimes also consciously break them. Think for instance of John Cage’s composition 4ʹ33“ in 1952, which provokes by performing 4 minutes and 33 seconds of silence while the musician behaves according to the typical conventions of a classical concert or of Peter Handke’s play Offending the Audience in 1966, which – by rejecting all expectations of a theatrical play – make the audience aware of their taking-for-granted thinking about what a play should be and thereby question these assumptions.

Coordination and cooperation imply constant friction and harmony, arguments and negotiations of standards, conflicting choices and social relationships. Participants in art worlds may not always share the same understanding of particular conventions. When practical disagreements occur, people negotiate their practical approaches – practical in the sense that disagreements are not abstract or theoretical, but are generally related to immediate actions. Therefore, social action is continually changing. Yet change is not democratic in the sense that all participants have an equal voice, and some participants are more persuasive than others. People with greater control over crucial resources can, to an extent and under certain conditions, prevail. However, this aspect of power relationships amid effective norms remains rather underexplored in Becker’s work.

4 Division of labor in art worlds

“Art worlds consist of all people whose activities are necessary to the production of the characteristic works which that world and perhaps others as well, define as art” (Becker 1982, 34).6 In any art world, there is a division of labor since any practitioner (e.g., an artist) depends to some degree on the contributions of others. As already mentioned, art worlds are interdisciplinary, that is, they integrate the work and competence of many different professionals: artists, producers of artistic materials and instruments, technicians, workers, agents, lawyers, managers, accountants, advertising people, journalists and so on. For Becker, all these people are equally important since the accomplishment of complex projects depends on their contribution. “Art is not an individual product” (Becker et al. 2006, 2). Becker’s sociological approach goes against the traditional individualistic approach that focuses on the role of individual artists – often using the mystifying figure of a genius or the glamorous metaphor of a star – while neglecting social embedding and the cooperative conditions of artistic work. From this perspective, Becker (1982, 194) argues that “it is not unreasonable to say that it is the art world, rather than the individual artist, which makes the work.”

The division of labor between members of art worlds – for example, creators and distributors –, is not natural or rational, but rather conventional. Roles and tasks result from negotiations, long-term social interactions and existing institutions (e.g., professional training and specialization). The higher status people, the core personnel (mostly the artists), hand over the more laborious and routine work to lower status people, the support personnel (mostly craftspeople or technicians). This does not mean, however, that the higher status artists are independent of the support personnel (as can be seen from the occasional strikes in Hollywood or trade union negotiations at city theaters). A painter cannot easily do without craftspeople for frames, canvases, brushes and colors, or without art dealers, curators and art critics to make their works known. In other words, an artist would not need support personnel if, and only if, the social organization of arts was radically different than it is in our times. Moreover, in a very fundamental sense, no artist would exist without an audience – to be is to be perceived (esse est percipi, as the Irish philosopher George Berkeley put it). The social existence of artworks depends upon whether they are perceived or not (Becker et al. 2006, 5).

Art worlds are complex networks of cooperating groups, and the relationship between artists and non-artists varies according to the specific project, the art form, institutional arrangements, general budget and particular economic interests, etc. In their creative activities, artists – Becker (1976, 43–54) distinguishes between different types of artists, for example, integrated professionals, mavericks, naïve and folk artists – are dependent on other members. However, they may not have the same aesthetic, financial and professional interests. Some orchestra players, for example, may be more interested in their own performance and attracting individual attention, than in the success of the orchestra as a whole. This even extends to sabotaging an artwork if the artistic personnel think it could harm them personally. Another example from Becker (1982, 68f.) is the collaboration of an artist with printing craftspeople who are specialists in lithography. If the artist wants to have what would otherwise be accidental printing errors on the prints, the lithographers may decline to follow the instructions because they want to protect their reputation as professionals. Here conventions of artists (core personnel) and craftspeople (support personnel) collide. We could add more examples of conflictual situations when artistic interests and economic interests stand in opposition, and the people involved fail to find a viable agreement.

5 Art worlds as a holistic approach

Art needs networks, and in order to network people need to communicate and cooperate in collectives. Without shared conventions of social exchange and artistic practice, cooperation would be highly unlikely. Therefore, without an agreement on conventions, which is mostly tacit, there would be no art worlds and no art. This is the main argument in Becker’s Art Worlds.

We believe Becker has a holistic approach to arts. He uses analytical categories like production, editing, distribution, marketing, evaluation, archiving, artists, support personnel, experts and audiences, yet he emphasizes the interrelation and interdependence of all of these categories. Furthermore, since he discusses permanent adjustments, variations and changes in collaborative situations, practices, evaluative standards and organizational settings, his conception of art worlds is dynamic. Consequently, ontologically speaking, artworks do not exist as stable entities but are in a continuous process of (re-)actualization and becoming (Becker 2006, 22f.). Becker does not overlook the existence of asymmetrical dependencies and power relationships, yet he rejects the idea of determination. He emphasizes that art worlds are in a constant drift and borrows the conceptual distinction made by Thomas S. Kuhn (1962) between incremental and revolutionary changes to distinguish between changes that question dominant ways of organizing cooperative activities, from profound changes that have a transformative impact on central (though perhaps not all) conventions and institutions with the effect that new art worlds emerge (Becker 1982, 301ff.).

An art world does not appear suddenly – rather it is a slowly structuring network of people, with successively adapting attitudes and practices, for example, of ideas of what art is. Becker avoids defining the term art and instead uses a definition that is as broad as possible, even if it entails circular reasoning. He deliberately does not distinguish between popular and high culture.

6 Extension of the art worlds perspective: the sociological focus on artworks

From the late 1990s, Becker became more interested in the sociology of the artwork, which we regard as an extension of his concept of art worlds. Questions about the conditions of artistic work (networks, conventions, career paths) moved into the background and Becker started focusing on the artistic creative process. At the center of his sociological research were now questions like, How will you know when the piece I’ve watched you working on is done? and What will you do with it now that it’s done? To answer such questions, he collaborated with some of his close colleagues and artist friends, among them Robert R. Faulkner, Richard Caves and Pierre-Michel Menger. This collaboration resulted in the anthology Art from Start to Finish (Becker et al. 2006), and its first chapter was entitled The Work Itself (Becker 2006). The qualifier itself indicates that sociologists should not interpret an artwork as a signifier for a specific meaning (e.g., as a reflection of social conditions or social structures), but should rather look at the work “for what it is just by existing” (Becker 2006, 21). Furthermore, itself should not be understood as an essentialist approach since Becker (2006, 22f.; see Danko 2015, 107f.) explicitly criticizes the idea of artwork as an autonomous entity. Instead, he acknowledges that artworks have a social life, that is, their individual use, meaning and value change. Distributors may promote them, but if the public (experts and audiences) loose interest in an artwork, then it dies and its social existence comes to an end. In all these phases, the quality and intensity of public interest may vary. There might be an emotional welcome, a bored or recalcitrant admission or a flat rejection (Becker et al. 2006, 5). The central question for Becker is the duration or stability of an artwork over time.7

A musicologist typically studies music pieces, the contexts of their creation and reception, and an art historian analyzes paintings or sculptures, their formal properties, references, allusions, artistic impact and so on. However, what is the object of an art sociologist? Sociologists mostly distance themselves from artworks and related aesthetic theories, and only look at the social contexts of production, distribution, valuation and reception or consumption of artworks. They focus on power relationships or on the social condition of artists, or they analyze institutional settings and their effects on arts – but they have rarely tried to investigate the work itself. In the introduction to their anthology, Becker, Faulkner and Kirshenblatt-Gimblett (2006) point out that they neither start with one theory (not even the art world concept), nor with a specific methodology of thinking (not even an interactionist position) to answer these questions. They let artists and art sociologists think about it in a transdisciplinary manner.

Becker et al. agree on the statement that social science can investigate the social life of artworks:

The focus remains on the artwork and the people who create, distribute and consume this artwork (2006, 3). If the artwork is the product of collective cooperation, if the creation of an artwork is an interactive process of materials and people [Becker et al. evoke Latour’s actant concept here], then the question remains, when is the artwork finished? What conditions must be fulfilled (and for whom?) to decide when an artwork is done? Thus, many ideas e.g., about a finished artwork are elusive (2006, 4ff.).

Although a sociologist does not need profound knowledge of art, it is nevertheless helpful to know more about it than a regular consumer. Furthermore, an important part of the methodology to conduct a sociology of the artwork is the sampling of cases to be studied. Becker et al. (2006, 13ff.) prefer the method of contrast sampling, for instance, selecting an artwork from a painter, a theatrical production, a novel and a composition, thereby picking a highly structured artwork (e.g., a meticulously conceived novel) and a highly spontaneous artwork (e.g., action painting or improvised performances). The methodology of case studies touches upon the issue of generalization. If you have a number of independent cases, how can you generalize them? Becker et al. (2006, 16f.) are not looking for statements that are true for all films, sculptures, music or other art forms. They admit that they are very case-specific in their research choices, so any generalized statement from this research can be set aside because there may be other cases that prove the opposite. However, even when choosing highly specific cases, they look for the “underlying dimensions of artworks and their making” (2006, 17). In sociological research on artworks, particularity is the norm. One has to look for the interesting case that cannot be generalized, “to think against the grain, and to embrace the unpredictable” (2006,18). Conventionality is avoided for the purpose of being interesting – unfinished musical fragments in jazz are regarded as complete. A typical problem of musicians is, What shall we play now? (2006, xxx) The answer may vary, as jazz musicians have standard tunes, classical musicians have written scores, but mbira players in Zimbabwe have no such collection of tunes and scores and thus improvise from beginning to end. Acknowledging the great variety of “musicking” (Small 1998) does not permit any form of generalization. By selecting very different artistic practices, sociologists are able to look for general topics. For instance, there is always the issue of getting things done in any artwork production, and Becker et al. (2006, 19) note “that most arts that have some history and some organization have conventional, if not traditional solutions to such problems.” By comparing different cases, sociologists can discover various resemblances in the process of art-making, from having an idea to the accomplished finish of an artwork. The claim made by Becker et al. is that sociologists can overcome the particularity of a singular case by discovering resemblances and analogies to other cases that are also backed by further research and analyses.

The principle of the fundamental indeterminacy of the artwork

The main argument for letting arts sociologists contribute to an analysis of an artwork is what Becker (2006, 22f.) calls the “principle of the fundamental indeterminacy of the Artwork.” He derives this principle from his observation that no permanent artwork is itself a stable entity: “It is impossible, in principle for sociologists or anybody else to speak of the ‘work itself’ because there is no such a thing” (2006, 23). This anti-idealist and anti-platonic position can also be found in earlier publications by Becker (1974). First, there are no clear and distinct criteria for defining what is an artwork, and second “there are only the many occasions on which a work appears or is performed or read or viewed [and] each can be different from all the others” (Becker 2006, 23). “And works will be different for people with different ages, genders, classes, emotional states. The ‘work itself’ may not be different, but the work the viewer takes in may well be” (2006, 24).8 A composer finishes a work, but the musicians who play this composer’s work create a sonic interpretation of the score and consequently a different finished work.

In an audience each person has a specific aesthetic experience in the context of their own enculturation and situational mood (see DeNora 2000), and each person perceives and creates a different musical work. Becker’s argument, to be clear, is neither derived from a subjectivist position (see Hume 1987 [1757]), nor from a particular semiotic theory (see Eco 1989 [1962]). The thrust of his argument is on the different occasions of the (re-)actualization and forms of engagement (variations in performance, different contexts of presentation, various experiential perspectives, and prefigurations of understanding) with artworks (see Dewey 1980 [1934]). Therefore, artworks are never the same, they vary and therefore they have plural modes of being. Still, people talk about artwork, and the question is how this paradox of indeterminacy and singularity can be solved. According to Becker (2006, 23), it is up to “competent members of an art world to decide when an artwork is the ‘same’ and when it is ‘different’” (e.g., whether the release of a Hollywood film is satisfactory to the director or whether he insists on a director’s cut). The central contribution of art sociology is to describe how many different “occasions on which a work appears” there are (2006, 23), and what the conventions are to increase or decrease the number of these various occasions (2006, 24).

For a better understanding of Becker’s viewpoint, we should note that most often he is implicitly or explicitly thinking of jazz musicians (see, e.g., 2006, 28). When a jazz band plays Take Five (composed by Paul Desmond), the musicians interpret the score in a distinct and creative way based on conventions of the jazz world (see 2006, 25). Their choices are finite, because they are usually made in routine ways or in the course of performing in a flow modus (Csikszentmihalyi 1990). Therefore, the main task of sociologists of music (and this distinguishes them from musicologists and music critics) is to find what conventions or routines are used to define “focused meanings” (Becker 2006, 26). Conventions are not social constraints but are, from an interactionist perspective, the result of practical negotiations. The analysis of these conventions and how they limit the number of an artwork’s meanings brings us back to the central theme of what the concept of art worlds represents.

7 Critique of Becker’s art worlds

Becker’s self-critique: skepticism of art worlds as collective entities

Characteristically, Becker often plays his own devil’s advocate. While he insists in Art Worlds (1982) that art is always produced in collectives, he looked and found examples of lone artists – so-called outsider artists – doing art all by themselves. In particular, the amateur artist Simon Rodia (1879–1965), who created the Watts Towers, fascinated him. Rodia emigrated from Italy to North America at the age of 15, had no professional artistic training and worked all his life outside of any art world (e.g., as a miner, a tile maker). So without any training or membership in any art world, Rodia built his towers with his own hands. When he was later asked who his role models were, he looked up some artists, and only then compared himself to Antonio Gaudí, an architect of Catalan modernism, who planned the Basìlica de la Sagrada Famìlia in Barcelona (Becker 1990, 499). Only much later, critics and architects recognized these kinds of amateur activities as artworks (and were then able to safeguard the Watts Towers from the wrecking ball).

This example gave Becker cause to reflect on his central thesis of art as collective action. Obviously, some people work literally alone and isolated from any art worlds. We may call them artists, but this ascription is, according to Becker’s interactionist perspective, only justified after there has been some recognition by significant others. The Watts Towers became artworks only after they had been attributed this status by a curator. Therefore, the case of outsiders does not necessarily contradict either Becker’s central thesis on the necessity of art worlds or Becker’s open and dynamic concept of artworks, since an artwork is not simply a material entity but includes processes of presentation, meaning-making, valuing, consuming, etc. From this perspective, an artwork has an ontological temporality and spatiality (see Becker et al. 2006, 6). Any conception of artworks that would deny the many different temporal and spatial contexts of its appearance would be essentialist and, oddly enough, asocial.

Becker’s neglect of external social structures

Becker’s emphasis on the agency of the members of an art world, on their ability to negotiate conventions and to experiment with new artistic means has been questioned by sociologists who underline the importance of power and dominance in social relations. For instance, the French sociologist Natalie Heinich (2000b, 161) criticized Becker for being too egalitarian and relativistic to the extent that he ignored the fact that “the singularity realm governs the domains of art in the modern era.” For Heinich, Becker’s perspective disregards the hierarchy of artistic values and the fight for recognition and higher social positions. Regarding social constraints, Robert Cluley (2012, 206ff.) refers to Richard Peterson and the Production of Culture Perspective (see chapter 6 in this book), but we also relate social constraints to Neo-Institutionalism (see chapter 7). Both underline that organizations form relatively stable units by establishing formal hierarchies and structuring decision-making processes. Furthermore, we extend this critical argument by referring to the influence of Michel Foucault’s (1991a [1975]) works on “disciplinary power” – think of the effects of contracts, plans, timetables, organograms and other managerial actions – and “governmentality” (Foucault 1991b [1978]), which have had a strong influence on organizational sociology (see Mackinlay and Pezet 2019). To be clear, Becker does show “the constraints on action by highlighting the power of conventions and the limits to structures by highlighting how actors innovate around conventions” (Cluley 2012, 204), but the structural argument of the concept of governmentality goes deeper. Techniques of governing form the subjectivities – the desires, projects, commitments and emotions – of people involved in art worlds. Thus, the agency that Becker ascribes to the members of art worlds is constitutively prefigurated by transindividual structures.

Although Cluley (2012, 208f.) defends Becker’s microsociological approach, he underlines the importance of language and the sociological analysis of language use. Language facilitates and enacts social structures (2012, 211) and specific language styles are practically effective in segregating insiders from outsiders of art worlds. “Language use does not just reflect the world. It reflects the position a speaker has taken to the world” (2012, 212). According to Cluley, the use of language shapes and defines art worlds. “Cultural texts allow people to interact and are produced by people interacting” (2012, 209). Consequently, studying art worlds should be completed by studying art words (2012, 214). “On this point, Becker does not offer us assistance but, as we shall see, methods developed in social psychology, organization theory and discourse analysis provide us with techniques that draw on structuration theory” (2012, 211).

Let us respond briefly to both critiques, governmentality and language use. Without doubt, issues of power have always been at the core of sociology of arts, and as Peter Martin (1995, 178) remarks, the art worlds’ perspective “is in no way incompatible with a recognition of the centrality of power and coercion in shaping the social order.” The Foucauldian perspective on power makes a strong claim: power is omnipresent, polymorph and penetrates every single moment and event in social life. However, the main argument of the art world perspective is that one cannot explain the social organization of arts entirely by deducing it from class structures, political and cultural power, economic interests or any other abstract term. Becker claims that organizational variation and contingence – or to put it on an epistemological level, questions about the social order – need to be answered empirically (see Martin 1995, 179). He pays attention to everyday practices and circumstances and does not think there are any hidden or mysterious forces steering social processes (Becker et al. 2006, 3).

The second point made by Cluley is related to the role of language in the social organization of art worlds. We do not regard Cluley’s argument as a fundamental critique of Becker’s approach since interactionist research does consider language and especially conversations in its analysis. Becker himself undertakes such an analysis for instance in Outsiders (1963), though less so in Art Worlds (1982) since in the latter he does not work with original empirical material. In Outsiders, Becker shows that language use not only confirms membership (speech communities are related to social communities), but also has an epistemic function. Conversations and the creation of particular symbolic expressions help people to make sense of their actions and social environment. However, in our opinion Cluley argues almost like a structuralist: “It is through language use that cultural producers draw limits to their art world…. The boundaries of art worlds are defined, therefore, by art words” (Cluley 2012, 213). He implicitly separates doings from sayings, giving language structural power. His theoretical position can be disputed: First, it seems to underestimate the role of tacit understandings. Second, doings may stand in significant tension to sayings since actors may deliberately say something but act differently. Third, Cluley seems to overlook the body and the embodied cognition of actors. Meaning-giving and boundary work are not solely linguistic acts, they are also corporeal acts.

The underexplored relationship between the inside and the outside of art worlds

Becker’s interactionist approach toward art worlds overlooks first the specific problem of the self-referentiality of modern art, which began approximately in the first half of the 19th century, and second the self-creation, the autopoiesis, of the art system, as the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann (2000a [1995]) phrases it (see chapter 4 in this book). In this theoretical context, Willem Schinkel (2010) states that, contrary to Becker’s argument, the structuring of art worlds as local collaborative networks takes place clearly outside of these art worlds. Communication about art does not take place between artists alone, but through gatekeepers that are not necessarily insiders of a local art world, that is, art theorists and art critics, art dealers, curators and theater directors, to name just a few. While Schinkel criticizes Luhmann’s operative closure (the splendid isolation of art systems), his critique is similarly applicable to Becker’s art worlds.

Consequently, the valorization of art, at least to a certain extent, is not made by artists nor by art lovers but largely by economic forces and influential art market players, and artists then adjust to these decisions (allo-reference becomes self-reference) or not.9 Yet communication about art is rarely communication that really concerns art itself. Frequently it is communication around art. Many contemporary artists are aware of this – that is why they often accentuate their lack of power to define art and reflect this contingency in their artworks (see Buchloh 1999; Bourriaud 2002) – and the crisis of art becomes a theme of art (Schinkel 2010, 278). The self-referentiality of art is thus engaged with ad absurdum by artists themselves, and external powers are included in the art worlds in order to preserve them. In other words, If you can’t beat them, let them join you. The irony of the artists’ powerlessness in the face of other socially more powerful subsystems (e.g., the economy) is taken up in contemporary art and made a theme by famous visual artists such as Judy Chicago, Hans Haacke and Barbara Kruger. The externalization of evaluating art has many dimensions. Schinkel believes that aesthetics is neglected in favor of content, and art becomes action art or conceptual art. The attributes of aesthetics are lost in the process of hyper-reflexivity; and the appreciation and valorization of art is replaced by an external indicator, its economic success. The market determines the value of art, and other factors become negligible (see Velthuis 2003, 2013). However, this thesis is contestable (see Klamer 1996, Heinich 2014, Buchholz 2022), and, frankly, valorization and markets are not at the core of Howard Becker’s art sociological works.

Endnotes

-

Bruno Latour would have suggested adding nonhuman actants to this network. In a later interview, Becker expresses great sympathy for Latour’s emphasis on the role of nonhuman entities (see Plummer 2003).↩︎

-

Although Becker highlights the production process, he is aware of the importance of consumption. “The consumers of the work also share in its production. The work has no effect unless people see it or hear it or read it and they do that in various ways, again depending on the social organization of the world in which the work is made” (Becker 2006, 24).↩︎

-

David Lewis uses the term conventions (for a definition, see Lewis 1969, 78) to explain linguistic communication. The claim that linguistic understanding and exchange is based on conventions (see Wittgenstein 1999 [1953], §355) goes against the idea that language is either natural or rational (based on explicit agreements), but underlines its contingency (see Shusterman 1986, 45f.).↩︎

-

The same goes also for the Neo-Institutionalists or the French scholars who developed the sociology of conventions. They argue that conventions inform and constrain actions, but do not determine them. These sociological theories thus overcome the dualism of structure and agency (see Biggart and Beamish 2003, 455–457).↩︎

-

Musical notation systems – whether the diatonic or the chromatic seven-step scale or the twelve-tone system – and the way musicians read them when they play are simply conventions. Similarly, a naturalistic painting, an impressionist, a cubist painting or an abstract informal painting differ since they are based on different painting conventions. Different conventions have a strong influence both on the creation of artworks and on the expectations and preferences of the audience.↩︎

-

There are similarities between Howard Becker’s (1982) art worlds and Etienne Wenger’s (1998) communities of practice, but these have not yet been systematically explored.↩︎

-

See Lena and Peterson (2008), who explored the concept of trajectories of music genres.↩︎

-

Becker’s distinction between the “work itself” and the work the viewer takes in is similar to the distinction in phenomenology between the material work of art and the mental object, the so-called aesthetic object (see Ingarden 1961).↩︎

-

This hypothesis is examined by Alison Gerber (2017) in her fieldwork, in which she observed and interviewed more than sixty visual artists in their art-making and their oscillation between a love of art and the need to make a living. She discovered that the shift of valorization from aesthetic admiration to economic value has a fundamental effect on the process of artistic practice. Nevertheless, according to her analysis, most artists still make art because it matters so much to them – despite the at times overwhelming economization of art-making.↩︎