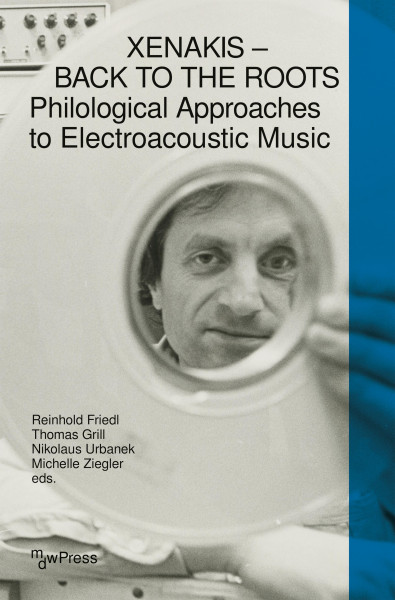

Curtis Roads

How to cite

How to cite

Outline

Outline

This is a personal account of the impact Xenakis had on my life over several decades.1 To be clear, I am not an expert on Xenakis’s life. These recollections view Xenakis through the narrow lens of my encounters with him. It has been wonderful to sift through my memories to reconstruct this narrative. To begin, it is important to describe the historical milieu of my earliest encounters with Xenakis. In 1970 I was a 19-year-old musician living in a commune in Urbana-Champaign, Illinois (home of the University of Illinois) with 24 other people. I was learning a great deal about the music business and becoming more and more disillusioned. At the same time, my aesthetic perspective was rapidly evolving. I was going to concerts of classical music at the university but also concerts of new experimental music. On my own I was experimenting with new sounds using available equipment.

By chance, in this period the University of Illinois was a pioneering centre for research in computer music. At the invitation of a graduate student friend, I started working in the EMS (University of Illinois Experimental Music Studio). The EMS was an excellent facility with an API mixing console, 4-track tape recorders, a large Moog synthesizer, and quadraphonic playback. This was a state-of-the-art analogue studio. My friend and I started making tape music pieces that we would play in various venues.

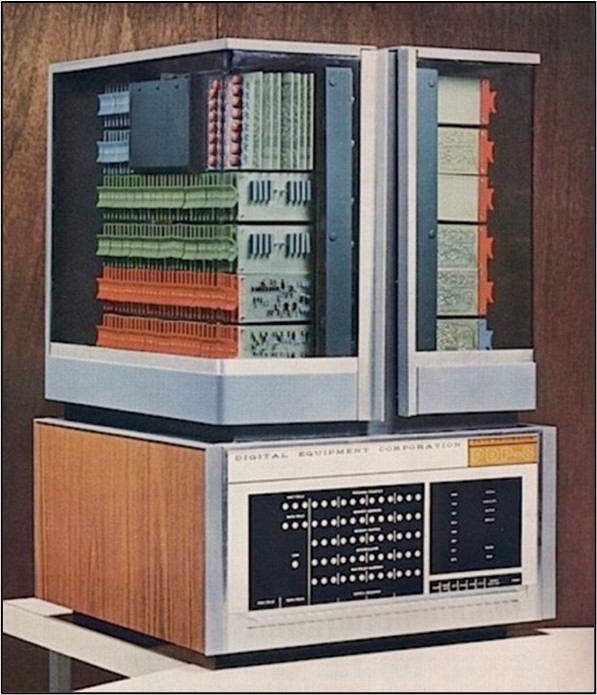

The EMS also had a Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) PDP-8 computer. It was the model with glass doors displaying the circuit boards. It was love at first sight for me. I saw the computer as a way to combine my intellectual and musical aspirations. I met Professor Herbert Brün, a pioneer of algorithmic composition and experimental digital synthesis, Professor James Beauchamp, a pioneer of computer sound analysis and synthesis, and researcher Edward Kobrin, a pioneer of real-time interactive composition. They were all generous with their time. I was given a printout of Max Mathews’s Music V program, written in Fortran, which I still have.

Figure 10.1: DEC PDP-8 computer. Photographer unknown.

Through recordings I became familiar with the music of Iannis Xenakis, beginning with Metastaseis (1954), Pithoprakta (1956), and Eonta (1964), the electronic works Concret PH (1958), Diamorphosis (1957), Orient-Occident (1960), and Bohor (1962), and the orchestra plus tape piece Kraanerg (1969).

First Encounter with Xenakis

In 1972 I saw a poster for Xenakis’s short course in Formalized Music at Indiana University. I decided to enrol. Xenakis lectured at a blackboard, detailing his theories in mathematical terms. In between the lectures he played his pieces at considerable volume over four Altec-Lansing Voice of the Theatre loudspeakers. Xenakis’s computer programming assistant, Cornelia Colyer, took us to the campus computer centre to show us plots of waveforms produced by dynamic stochastic synthesis (Xenakis 1971: 247).

Figure 10.2: Poster for the Seminar on Formalized and Automated Music at Indiana University, 1972. Courtesy of the Author.

My encounter with Xenakis was life-changing. It gave me clear focus and direction, which was crucial in my university studies. The idea of using algorithmic processes in music composition attracted me from an intellectual standpoint as a formidable design problem.

I came away from Xenakis’s course with two specific goals. First, I wanted to learn how to program computers to model stochastic processes for composition. For the design of new structures such as what Varèse called ‘sound masses’ (Varèse and Wen-Chung: 1966) and Xenakis called ‘clouds’, a stochastic model seemed an appropriate starting point. Second, I was intrigued by the concept of granular synthesis of sound. We heard no sound examples but the theory fascinated me.

Several weeks later I visited Stanford University in California. John Chowning gave me a tour of the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory where the computer music centre was housed. It was a revelation. I saw advanced technology that was ten years ahead of its time. In the summer of 1972, I began to learn computer programming languages. The first was Fortran IV, in order to analyse Xenakis’s Stochastic Music Program. I created a flow chart based on the analysis (Roads 1973). In the fall of that same year, I enrolled as a student in music composition at CalArts (California Institute of the Arts) in Los Angeles. CalArts had just opened so everything was new and exciting. The faculty could not understand why I was interested in Xenakis’s methods, but my fellow student composers did.

In that period, the institute had a single computer: a Data General Nova 1200 with an attached teletype printer and paper tape reader. I started studying with the mathematician Leonard Cottrell. We learned programming and digital circuit design. I began to write programs that implemented the formulas in Formalized Music. Then I started writing my own composition algorithms.

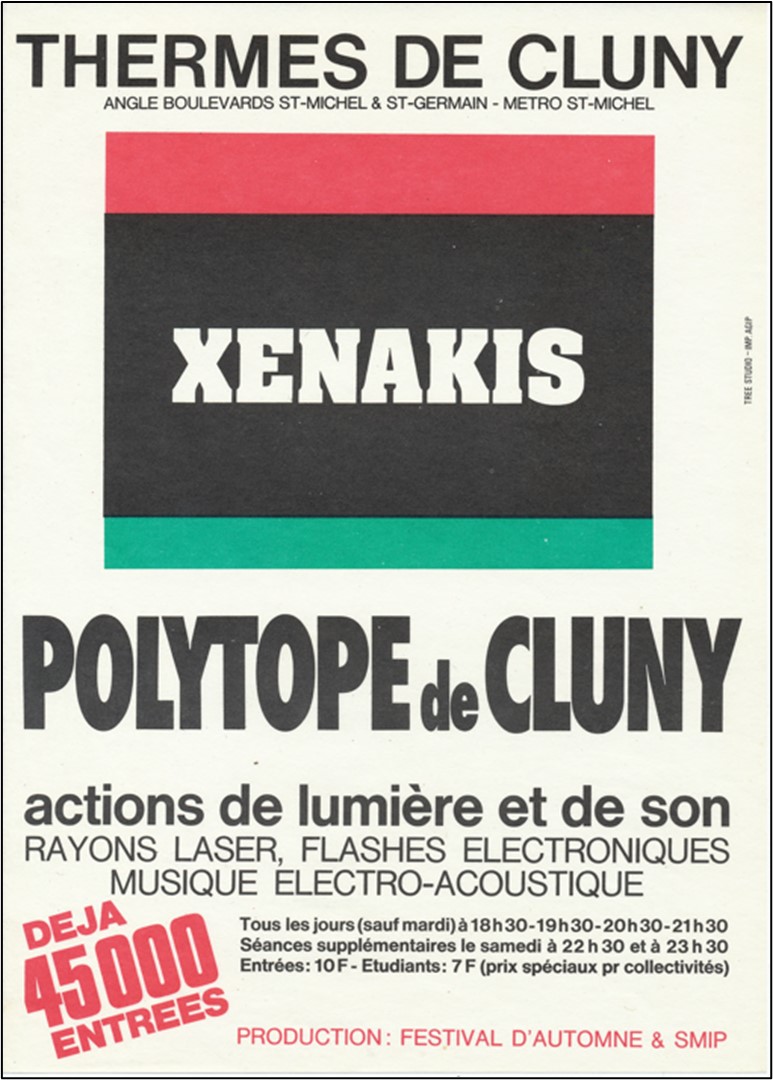

Figure 10.3: Poster for Polytope de Cluny. Courtesy of the Author.

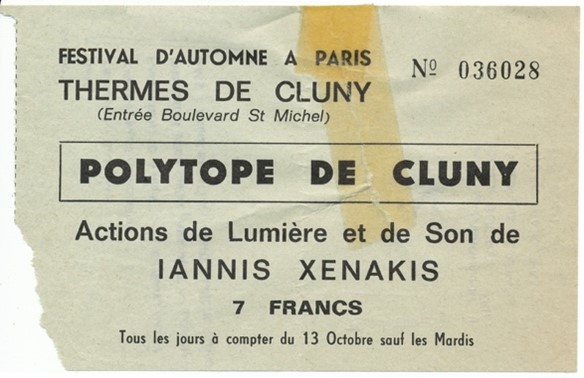

In 1973 I flew to Paris to attend the Festival d’Automne. The main goal of my visit to Paris was to experience Xenakis’s sound and light spectacle Polytope de Cluny (1972) in the medieval Musée de Cluny.

Figure 10.4: Ticket for Polytope de Cluny. Courtesy of the Author.

Figure 10.5: Polytope de Cluny. Archives Les Ateliers UPIC, Paris.

Polytope de Cluny was experienced lying on one’s back, looking up. A robotically-controlled laser projection system created moving geometric forms. An interesting aspect of this movement was its stepped rather than smooth motion, which emphasized the element of digital control in discrete steps. High on the ceiling was a metal grid with hundreds of flashbulbs following a digital script. Meanwhile the intense 27-minute octophonic tape of Polytope de Cluny filled the hall. I experienced it eight times. The design of Polytope de Cluny was extremely impressive both technically and aesthetically. In Paris I also attended lectures and concerts featuring Karlheinz Stockhausen. I was disappointed by a performance of Hymnen for tape and orchestra.

Returning to California, I was determined to synthesize granular sound by computer. In 1974 I left CalArts for the UCSD (University of California, San Diego) where they had a working computer sound synthesis system. Later I will talk about my involvement with granular synthesis by computer.

In 1980 I moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts to work at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology). I was editor of Computer Music Journal and a researcher at the MIT EMS (MIT Experimental Music Studio). At the insistence of Barry Vercoe, my boss at MIT EMS, I appointed Pierre Boulez to the Editorial Advisory Board of Computer Music Journal. Throughout his life, Boulez went out of his way to criticize electronic music as a compositional medium. The IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique) centre in Paris, founded by Boulez, was notorious for excluding electronic music composition as a legitimate artistic medium.

In 1981, IRCAM organized a conference on “The composers and the computer” (Roads 1981). This is where I first met Boulez in my official role as editor. He initiated the conversation with a surprisingly direct question: “What are we [i.e., you] going to do about Xenakis?” To put this in context, Xenakis had recently written a criticism of IRCAM in a major Parisian newspaper (Xenakis 1981). My response to Boulez was equivocal. I observed that Xenakis’s ideas were sometimes fuzzy. Boulez replied with a pun that Xenakis was fussy. That was the end of the conversation. It was a political test.

During the same conference, I visited the CEMAMu (Centre d’Études de Mathématique et Automatique Musicales) in Issy-les-Moulineaux to see a demonstration of the UPIC (Unité Polyagogique Informatique du CEMAMu) system by Xenakis and his assistant Cornelia Colyer. Guy Médigue, the lead engineer of the UPIC, was also present.

Three years later, IRCAM organized the 1984 International Computer Music Conference. Once again, I took a side trip to visit the CEMAMu. Following this visit, I asked Xenakis to contribute to my book Composers and the Computer. He wrote the excellent essay “Music composition treks” to the anthology (Xenakis 1985).

In the summer of 1987, I had a residency in Paris as a visiting composer at the CEMAMu, working with the UPIC system. The 1987 version of the UPIC system introduced the possibility of drawing sampled sounds, not just synthetic waveforms. I brought a tape of alto saxophone tones. My UPIC scores created saxophone glissandi that would be impossible to achieve using the MUSIC-N style programming languages of the time. Of course, the UPIC did not run in real-time. You had to draw the score using ink on a large roll of paper, then manually trace every line in order to enter it into the computer. Then you would give the command to start sound synthesis calculations. Rendering a page to sound took time. The UPIC system ran on a Thomson Solar 16-bit minicomputer, which was slow.

In 1991, after the departure of Pierre Boulez from IRCAM, I was invited to work there as part of the regime change. In 1993 I left IRCAM to teach at Les Ateliers UPIC in the suburb of Massy. This felt like a homecoming. It was in this period that I came to know personally Xenakis and his circle. Of course, he was the famous maestro and I was an acolyte. I did not work directly for him, but was rather a part of the team at Les Ateliers UPIC working in parallel with CEMAMu. In my interactions with Xenakis, what struck me about him is that he was direct, unassuming, and without pretence. To accomplish what he did he had to be extremely confident, but this was never on display. His personality was formed in the crucible of the World War II resistance. Perhaps because of this, he exuded an aura of comradeship, rather than elitism. His team at the CEMAMu was lucky to have such a benevolent boss.

As a composer, Xenakis was always more radical than me. In 1994 I was present at the Paris premiere of his electronic composition S.709 (1994) in the auditorium of Radio France. This piece is the raw output of his experimental GENDY stochastic synthesis algorithm – untouched by human hands. The sound is harsh and abrasive, and the structure is bizarre. It was deliberately provocative. By contrast, I abandoned algorithmic composition in my youth because I found that beautiful algorithms rarely produced beautiful music. As a result, my practice is deeply entwined with craft and refinement. I take a multiscale approach to editing and mixing that takes place over a time scale of years. For example, my piece Then (2016) was the result of over 500 submixes in the period from 2010 to 2016. I use algorithms at the level of sound synthesis, but my pieces are carefully stitched together by hand.

Granular Synthesis

The most obvious connection between Xenakis and me is granular synthesis. It was, of course, Xenakis’s concept. I found it in his book Formalized Music (1971). He cited Dennis Gabor (1946, 1947) as the source of the scientific theory. Later in Paris Xenakis gave me a copy of Hermann Scherchen’s journal Gravesaner Blätter with Xenakis’s 1960 article on granular synthesis. It is a prized possession.

In March 1974, I transferred to UCSD specifically because I heard that they had facilities for computer sound synthesis. The researcher Bruce Leibig had recently installed the Music V program (Mathews 1969) on a mainframe computer housed in the UCSD Computer Center. The dual-processor Burroughs B6700 was an advanced machine for its day, but sound synthesis was difficult, due to the state of input and output technology in the early 1970s (Roads 2001).

Nonetheless, I managed to test the first implementation of digital granular synthesis in December 1974. For this experiment, called Klang-1, I typed each grain specification (frequency, amplitude, duration) on a separate punched card. A stack of about 800 punched cards corresponded to the instrument and score for 30 seconds of granular sound. Following this laborious experience, I wrote a program in the Algol language to generate grain specifications from compact, high-level descriptions of clouds. Using this program, I realized an eight-minute study called Prototype (1975). These were the earliest manifestations of granular synthesis by computer.

Les Ateliers UPIC

Next, we look at another point of encounter with Xenakis. The story of Les Ateliers UPIC is told in the book From Xenakis’s UPIC to Graphic Notation Today (Weibel, Brümmer and Kanach 2020), which is a free download from ZKM Karlsruhe.

As previously mentioned, in 1993 Gérard Pape asked me to teach at Les Ateliers UPIC. I already knew the UPIC system, but this was a new version that ran on a Windows computer with a dedicated hardware synthesizer, enabling it to operate in real-time. Les Ateliers UPIC was a small organization supported by the French Ministry of Culture. I became directory of pedagogy and led a year-long course. The course was a general introduction to computer music, based on my textbook The Computer Music Tutorial, which was in production at MIT Press. I also managed to conduct research, in particular the development of the first standalone app for granular synthesis: Cloud Generator. It was written by me and John Alexander, a student at Les Ateliers UPIC, in 1995.

Figure 10.6: Les Ateliers UPIC, Massy (suburb of Paris). 1995. Music historian Harry Halbreich, Curtis Roads, Brigitte Robindoré, Iannis Xenakis, Gérard Pape. Photo by the author.

I recall demonstrating Cloud Generator to Maestro Xenakis. His only comment was: “At least it doesn’t sound terrible.” Coming from Xenakis, who was not easily impressed, I took this as a compliment.

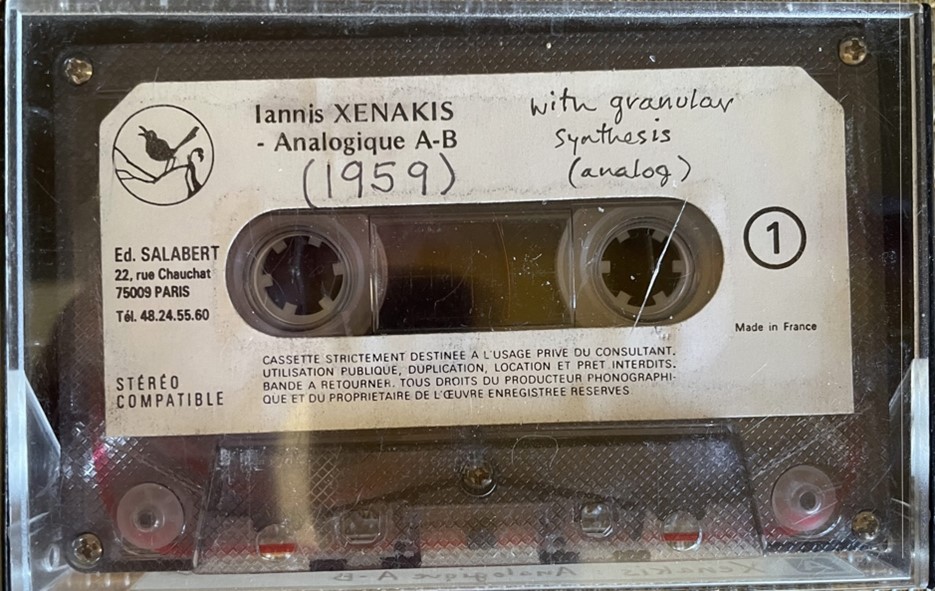

After I showed Cloud Generator to Xenakis’s publisher, Radu Stan of Editions Salabert, he slipped me a cassette of Analogique A et B (1959), which was Xenakis’s first attempt to realize granular synthesis using analogue tape. I had never heard it before. So, 21 years after my first computer experiments, I finally heard the original analogue granular synthesis!

One of the highlights of my experience at Les Ateliers UPIC was a concert organized by Gérard Pape at the Salle Olivier Messiaen of Radio France in Paris. This included the full Acousmonium setup of 48 loudspeakers. This was an extraordinary experience. Upmixing my music on the Acousmonium spatial panorama made an indelible impression.

In 1996 I became a professor at UCSB (University of California Santa Barbara). I returned to Paris annually to teach at the UPIC centre (renamed the Centre de Création “Iannis Xenakis” or CCMIX) until 2007. It was through CCMIX that I met Luc Ferrari and Bernard Parmegiani, among others. Les Ateliers UPIC/CCMIX was an open door to many artists.

Figure 10.7: Cloud Generator (1995) by Curtis Roads and John Alexander. Photo by the author.

Figure 10.8: Analogue cassette of Analogique A et B. Photo by the author.

Continuing the Granular Model

Here in Santa Barbara, I have continued to advance the granular model. The 1997 constant-Q granulator, written in SuperCollider, was the first program to apply an individual bandpass filter to each grain. This is an example of what I call ‘per-grain signal processing’, where each grain has its own envelope, waveform (or sample), amplitude, frequency, spatial position, filter centre frequency, and resonance. Per-grain processing is essential to create rich multidimensional textures.

In 2005, my graduate student David Thall coded the EmissionControl granulator, which implemented my concept of per-grain processing but also added a modulation matrix for automatic LFO control of certain parameters. A ramp function, for example, might modulate grain density over a period of a minute, while the user was changing other parameters manually.

Figure 10.9: SCATTER, screen shot by the author.

Another important research direction has been the creation of an analytical counterpart to granular synthesis (Sturm et al. 2009). We faced two major challenges. The first was computation time. Our atomic decomposition algorithm took 200 seconds to analyse one second of sound. Due to excessive computation times, we also had to limit the audio resolution of the resynthesis. The other major challenge was the conundrum of dark energy interference terms. Although our funding was not renewed, these issues are tractable engineering problems, but they require additional research. Beyond that is the issue of building compositional tools based on this approach. We built a prototype time-frequency editor called SCATTER, but such a model could be taken much further.

The original EmissionControl granulator only ran on old Apple G5 computers, so I was anxious to create a new app. The original goal was simply to recreate EmissionControl for modern computers. As we proceeded however, it became clear that EmissionControl2 went far beyond the earlier program.

In October 2020, we released a new EmissionControl2 or EC2. EC2 is designed as a laboratory instrument for research in granular synthesis.

Figure 10.10: EmissionControl2, screen shot by the author.

The main features of EC2 are:

-

Per-grain signal processing

-

Granulation of multiple sound files simultaneously

-

Up to 2,048 simultaneous grains

-

Synchronous and asynchronous grain emission

-

Intermittency control

-

Modulation control of all parameters with six LFOs (bipolar or unipolar waveforms)

-

Real-time display of peak amplitude, active grains, waveform, scan range, scanner, and grain emission

-

Scalable graphical user interface (GUI) and font size

-

Easy mapping of parameters to any MIDI/OSC continuous controller

-

Algorithmic control of granular processes via OSC scripts

-

Unique filter design optimized for per-grain synthesis

-

Unlimited user presets with smooth interpolation for gestural design

-

Open source code and free to download

Since its release, EmissionControl2 has been downloaded by over 7,500 musicians around the globe.

Finally, I should mention my new book The Computer Music Tutorial, Second Edition, which presents Xenakis’s Stochastic Music Program, and devotes chapters to granular synthesis and atomic decomposition of sound.

Xenakis said that he composed in order to feel less miserable (Lohner 1986: 54). This is an excellent reason. But the effect of music goes beyond one’s self. Composition is a service to humanity. Through music, a composer can make other people feel less miserable.

Endnotes

-

A later version of this chapter also available as Roads 2024.↩︎

Bibliography

Gabor, D[ennis] (1946) “Theory of communication”, in Journal of the Institute of Electrical Engineers Part III, 93: 429–457.

Gabor, D[ennis] (1947) “Acoustical quanta and the theory of hearing”, in Nature 159 (4044): 591–594.

Harley, James (2004): Xenakis: His Life in Music, New York: Routledge.

Lohner, Henning (1986) “Interview with Iannis Xenakis”, in Computer Music Journal 10/4, 50–55.

Mathews, Max (1969) The Technology of Computer Music, Cambridge: MIT Press.

Roads, Curtis (1973) “Analysis of the composition ST/10 and the computer program Free Stochastic Music by Iannis Xenakis”, student paper, unpublished.

Roads, Curtis (1981) “Report from the IRCAM Conference on The Composer and the Computer”, in Computer Music Journal 5/3, 7–27.

Roads, Curtis (2001) Microsound, Cambridge: MIT Press.

Roads, Curtis (2023) The Computer Music Tutorial, 2nd ed., Cambridge: MIT Press.

Roads, Curtis (2024) “La Légende de Xenakis: Meta Xenakis”, in Meta-Xenakis: New Perspectives on Iannis Xenakis’s Life, Work, and Legacies, ed. by Sharon Kanach and Peter Nelson, Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 409–428.

Roads, Curtis, Kilgore, Jack, and Duplessis, Rodney (2022) “EmissionControl2: designing a real-time sound file granulator”, in Proceedings of the 2022 International Computer Music Conference, San Francisco: International Computer Music Association.

Sturm, Bob L., Roads, Curtis, McLeran, Aaron, and Shynk, John J. (2009) “Analysis, visualization, and transformation of audio signals using dictionary-based methods”, in Journal of New Music Research 38, 325–341.

Thibaut, Jacques (2016) “Iannis Xenakis: musique et probabilités”, Centre Iannis Xenakis, Université de Rouen, Normandie; https://www.canal-u.tv/chaines/univrouen/iannis-xenakis-musique-et-probabilites (accessed March 1, 2023).

Varèse, Edgar, and Wen-Chung, Chou (1966) “The liberation of sound”, in Perspectives of New Music 5/1, 11–19.

Weibel, Peter, Brümmer, Ludger, and Kanach, Sharon, eds. (2020) From Xenakis’s UPIC to Graphic Notation Today; https://zkm.de/en/from-xenakiss-upic-to-graphic-notation-today, (accessed March 1, 2023).

Xenakis, Iannis (1971) Formalized Music, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Xenakis, Iannis (1981) “Il faut que ça change!”, in Le Matin, 26 January 1981, 28.

Xenakis, Iannis (1985) “Music composition treks”, in Composers and the Computer, ed. by Curtis Roads, Los Altos: William Kaufman, 169–192.

List of Figures

Figure 10.1: DEC PDP-8 computer. https://www.old-computers.com/museum/computer.asp?st=1&c=780, accessed March 29, 2023.

Figure 10.2: Poster for the Seminar on Formalized and Automated Music at Indiana University, 1972. Courtesy of the Author.

Figure 10.3: Poster for Polytope de Cluny. Courtesy of the Author.

Figure 10.4: Ticket for Polytope de Cluny. Courtesy of the Author.

Figure 10.5: Polytope de Cluny. Archives Les Ateliers UPIC, Paris.

Figure 10.6: Les Ateliers UPIC, Massy (suburb of Paris). 1995. Music historian Harry Halbreich, Curtis Roads, Brigitte Robindoré, Iannis Xenakis, Gérard Pape. Photo by the author.

Figure 10.7: Cloud Generator (1995) by Curtis Roads and John Alexander. Photo by the author.

Figure 10.8: Analogue cassette of Analogique A-B. Photo by the author.

Figure 10.9: SCATTER, screen shot by the author.

Figure 10.10: EmissionControl2, screen shot by by the author.