How to cite

How to cite

Outline

Outline

The Production of Culture Perspective is represented by a number of loosely connected, mostly North American sociologists who take an empirical approach. They focus on organizational factors that enable or impede the production of arts and culture in organizational settings. This approach is primarily associated with the name of Richard A. Peterson (1932–2010). The formation and transformation of cultural goods, including artistic content, can only be explained within the context of the concrete, that is, material steps of creation, distribution and consumption. The emergence of this perspective can be traced back to a thematic panel at the annual conference of the American Sociological Association in 1974, organized by Peterson and entitled, Culture and Social Structure: Production of Culture, with a presentation by Peterson under the all-encompassing title The Sociology of Culture. Two years later, Peterson (1976a) published an anthology with the same title and eight contributions that promised to investigate the social processes that shape the form and content of cultural production (Peterson 1976b, 14f.; 1979, 139; 1994, 165; Peterson and Anand 2004, 311).

The Production of Culture Perspective emerged in a specific sociological situation (see DiMaggio 2000; Nathaus and Childress 2013; Peterson 1979; 2000, 231f.). After the Second World War, only a few sociologists in North America were interested in arts and culture (see Foster 1989, 2–4; Ryan 2000, 92). Those few, familiar with the work of predecessors like Max Weber (1958 [1921]) and Georg Simmel (1916), were mostly influenced either by interpretive and hermeneutic art studies (e.g., Haskell 1962; Panofsky 1955), or by Marxist art historians and the reflection theory1 (e.g., Hauser 1999 [1951]; Schapiro 1977 [1936]). Within the broader sociological framework, systems theory had a dominant position in the 1950s. Systems theory in the Parsonian version mainly understood culture as a set of norms and values that latently steer social action. However, beginning in the 1960s, critical approaches with a neo-Marxist background (e.g., the Frankfurt School and the Birmingham School of Cultural Studies) became widespread. The influence of Symbolic Interactionism also increased and began to oust Parsonian functionalism. On a societal level, sociologists witnessed an expanding arts sector (e.g., an increasing number of museums, theaters, publishers, concert venues and their visitors); an unprecedentedly widespread commercialization of popular culture; and various fusions of traditional highbrow and lowbrow arts (e.g., pop art or free jazz), which together lead to a greater diversity of tastes (Gans 1974; Abbing 2022). These transformations indicate that arts started to play a central role in modern societies, particularly for distinct social groups (e.g., youth, cultural minorities); it was thus no longer possible to consider arts and culture as a peripheral topic in sociology (Denisoff and Peterson 1972; Peterson 1979).

In addition, some sociologists argued – like Adolph S. Tomars in his Introduction to the Sociology of Art – that if there was a genuine sociological perspective on art at all, then it would be an institutional perspective, that is, sociology “is interested in art as an institution (a system of institutional procedure)” (Tomars 1940, 19; see Albrecht 1970). Roger L. Brown (1968, 614f.) suggested asking how “mass production techniques (and the bureaucratic, formal organizations that go with them)” influence the creative process, production and circulation of popular arts (see Peterson 1979, 139). These ideas implied that the sociology of art is related to other sociological subdisciplines – for example, Rudolph Morris (1958, 317) referred to intrinsic relations to “the sociology of ideas … to the sociology of knowledge … to the sociology of change, and [to] urban and industrial sociology,” since “the organization of arts deserves our attention.” Therefore, the increased significance of a sociology of arts in the 1970s in North America was based on the opening up of this subdiscipline to other sociological areas (see LaChapelle 1984). Other sociological subfields provided role models with which to compare, contrast and replicate. Examples include the study of networks, contracts and unions in artistic professions; the acquisition of findings from industrial and organizational sociology; and the integration of technological changes in the analysis of arts production. Such cross-disciplinary approaches have generated a new view of arts and helped to overcome idealistic conceptions, for example, the exceptionality of arts or romantic ideas such as the image of the alienated artist. These crosscurrents enabled an unprecedented flourishing of the sociology of arts. This development was characterized – at least within the United States2 – by a turn toward empirical research on aspects of production, distribution and consumption of arts, leaving behind grand theories, for example, Marxist reflection theory or the Parsonian correspondence theory of values and social structure (see Peterson 1979; Nathaus and Childress 2013; Quemin 2017).

Clearly the Production of Culture Perspective does not claim to be a universal theory since it is based on empirical findings that correspond to a particular historical situation. It thus represents a middle-range theory (in the sense of Robert Merton 1968 [1949]). Therefore, various representatives of the Production of Culture Perspective criticized the functionalist understanding of culture as a set of norms that provide orientation, as well as critical approaches to mass culture resulting from a normative distinction between high and low arts, serious versus commercial arts, and the idea of a radical opposition between the economic and the aesthetic realm (Peterson 1976b, 7–14; 2000, 226–228; DiMaggio and Hirsch 1976, 74; DiMaggio 2000, 123f.). Although the Production of Culture Perspective suggests that the analysis of institutional and organizational conditions may help to explain changes of cultural production, it does not produce a general theory; rather, it emphasizes the historical and geographical contingence3 in cultural formations. Factors that were relevant in North America in the 1950s did not necessarily have the same significance in other countries.

The influence of American pragmatism on the Production of Culture Perspective was indirect and has not yet been sufficiently explored (see Joas 1993, 14–53). Certainly, John Dewey criticized the traditional equation of culture with high arts as a prejudice that obscures the plurality of artistic practices, expressive forms and aesthetic experience (Dewey 1980 [1934], 6; see Gans 1974). He therefore argued that the social character of aesthetic phenomena should be emphasized, and he conceived of the task of the philosophy of art as “recovering the continuity of aesthetic experience with normal processes of living” (Dewey 1980 [1934], 10). His aesthetics offer philosophical arguments for overcoming the dichotomy between fine and popular arts. From a sociological point of view, this approach led directly to the analysis of the social organization of cultural production.

Those representing the Production of Culture Perspective trace their sociological lineage to Robert Merton and his analysis of the relations between science and society (see Crane 1976, 72; Peterson and Berger 1975, 158), to Charles Wright Mills’ concept of “cultural apparatus” as an agglomerate of various organizations and milieus (see DiMaggio and Hirsch 1976, 74; Peterson and Anand 2004, 312), to Arthur Stinchcombe’s inquiries on the effects of the organization of work on production, and to Jacques Ellul’s analysis of how new techniques and technologies underlie social and cultural change.4 With this rich backdrop of inspiration, the Production of Culture Perspective analyzes contexts in which arts and culture are made and remade, since “cultures simply cannot be understood apart from the contexts in which they are produced and consumed” (Crane 1992, ix; see Peterson 1976b, 11, 13; Zolberg 1990, 9). Admittedly similar contextual approaches were formulated in earlier decades, for example, by Howard Becker (1951, 1976) or by Harrison and Cynthia White (1965). However, the main difference from Becker’s interactionist approach is Peterson’s and White’s emphasis on an approach to the production of culture that was relational, organizational and systemic. Nevertheless, it is generally acknowledged that both perspectives are related and complement each other.5

In this chapter we will focus on the sociological contribution of the prime initiator of the Production of Culture Perspective, Richard A. Peterson (1932–2010), but we will also look at the work of Diana Crane, Paul DiMaggio, Paul Hirsch and others. Since we refer to a network of sociologists that constitute the Production of Culture Perspective, we have decided to forgo individual biographical information.

1 Key terms of the Production of Culture Perspective

The Production of Culture Perspective incorporates views from the sociology of organizations, industries, and occupations in arts and in popular culture (see DiMaggio and Hirsch 1976, 74f.). The Production of Culture scholars use the term culture to refer to the realm of expressive-symbolic production. Culture includes therefore not only arts, but also sciences, religion, media and fashion. Instead of claiming a particular status for arts – for example, autonomy, singularity and exceptionality – Peterson (1976b, 12f.) looks for commonalities and suggests a comparative analysis of different cultural domains (see Crane 1972, 129–142; 1976, 57–72). Furthermore, since he regards culture as socially produced, he suggests highlighting “the complex mediating infrastructure” between creators and consumers (Peterson 1976b, 14) in order to overcome individualist (e.g., the creative genius view) explanations of culture (see Peterson 1979; Peterson and Anand 2004, 312). This mediating infrastructure includes financial and technological means, but also human intermediaries in various positions.

In an analogous way, the term art has a comprehensive meaning that aims to leave behind exclusive doctrines and professional ideologies that devalue the activities of outsiders, amateurs and minorities, for example, immigrant, indigenous and other marginalized communities.6 The general attitude toward arts is dispassionate: making art should be conceived as a sociocultural process embedded in particular industries, organizational arrangements, networks, reward systems, gatekeeping and acts of mediation (Peterson and Berger 1975, 158; Crane 1976; Santoro 2008b, 34f.). In this sense, scholars of the Production of Culture Perspective regard contemporary artistic production as the result of collective effort under certain conditions (e.g., cultural patronage, entrepreneurship or nonprofit organizations). Therefore, they are well aware that the various concepts of art are never free of social biases (see DiMaggio 1987a).7 This insight implies a certain level of skepticism toward aesthetic value judgments in scholarly research. In a later interview, Peterson (in Santoro 2008b, 35), while making a critical reference to Adorno’s pejorative judgments on jazz and rock music, (2008b, 38) emphatically insisted that his personal musical preferences – he was a passionate piano player – were always irrelevant to his sociological analyses.

The term production is understood in “its generic sense to refer to the process of creation, manufacture, marketing, distribution, exhibiting, inculcation, evaluation and consumption” (Peterson 1976b, 10). Production thus relates to a chain of interconnected activities that go beyond the completion of a cultural product, as it also refers to the interrelation of creators, distributors and consumers (see Alexander 2021, 61–64).8 Moreover, in these early years Richard Peterson and David Berger (1975) spoke of “cycles” in cultural production, referencing a market model that consists of successive phases of innovation, product development and successful market placement; the achievement of market dominance through vertical and horizontal integration, market saturation, stagnation and crisis. In the 1970s, their research focus was on the analysis of “the three key areas of production … [in the music industry, which are] artistic creation, merchandising and distribution” (Peterson and Berger 1975, 169). Many of their research interests targeted the interrelation between the organization of cultural production and its outcome (e.g., art forms, styles, content), asking how markets encourage or constrain artistic decisions and how particular audiences affect cultural organization (Hirsch 1978, 317; Peterson and Berger 1975). Later, from the 1990s onwards, Peterson put more emphasis on how consumption influences production, as he came to acknowledge that consumption includes meaning-making and valuing. Consumers are therefore not a passive but a productive force in cultural change. Anticipating the concept of prosumers, he spoke of the “autoproduction” of culture which points at the consumers’ appropriation, modification and recombination of cultural and aesthetic symbols, leading to new social uses and new forms of cultural expression (Peterson 2001; Peterson and Anand 2004, 324; Santoro 2008b, 49).

The Production of Culture Perspective puts much emphasis on structuring processes and on structural constraints (Peterson 1985; 1990). Subsequently, additional key terms are the industrial and organizational structures of cultural production (DiMaggio and Hirsch 1976, 73–90; Peterson 1986, 161–183; Blau 1992, 73–113). However, despite the apparent stress on organizational factors, Peterson also assigns individual agents an important role in cultural production. the Production of Culture Perspective cannot be classified only as a dichotomy of individualism versus collectivism or agency versus structural determination, but as a spectrum between these poles, with organizations as an outcome of both, that is, agents in the industry and structures of the sector (Anand 2000, 173f.).

In the first instance, organizations are social entities characterized by various structural intensities regarding formalism and boundaries. They emerge around certain tasks, which in arts are mostly related to artistic production, distribution of artworks and associated services. In order to fulfill their goals, organizations plan their actions, select according to their cognitive schemas between alternative options, face specific problems and seek solutions that seem appropriate, convenient or acceptable to their stakeholders. In order to operate, they need material and immaterial resources, and this generates a constant subliminal pressure on cultural production. From work that had already been done in organizational research – DiMaggio (2000, 128) refers to “a distinct affinity to the perspective of James March, Herbert Simon and the Carnegie School of organization theory” – scholars of the Production of Culture perspective knew that formal structures and bureaucratic internal processes of the (at that time) prevalent industrial age not only shaped the output of arts organizations top-down (see, e.g., Peterson 1982, 143–153), but also the thinking, behavior and professional roles of people working in these organizations (DiMaggio 1987b; Peterson 1986, 161–183). The insights afforded by industrial power structures were the starting point of the Production of Culture Perspective (DiMaggio and Hirsch 1976, 75; Peterson and Berger 1975, 159; Peterson 1982, 143), though various scholars analyzed different topics. For instance, DiMaggio and Hirsch (1976, 79–84) looked for structural tensions, such as between innovation and control, individual creativity and managerial ruling, or between various evaluative perspectives. Useem (1976) observed the political environment of arts organizations and asked how cultural policies and public funding influence organizational policies.

The metaphor of gatekeeper complements the structure-oriented view on cultural production (see Becker 1976; Bystryn 1978; Hirsch 1972; Kadushin 1976). This term refers to professionals like arts managers, administrators, curators, critics, censors (Peterson 1976b, 15), and occasionally to organizations and institutions that prestructure the selection and presentation of cultural goods in markets, in exhibition and performance venues, and in public mass media (Crane 1987, 110ff.). This focus on powerful individuals goes hand in hand with the assumption of key occupational positions and their preponderance in certain cultural areas. Diana Crane (1992, 70ff.; see Hirsch 1978, 315) sees two different types of gatekeeping processes: The first concerns the production and presentation of an artistic work, that is, financing the production costs and enabling production. The second follows the dissemination of an artistic work. In this case, gatekeeping occurs in those areas that are involved in the formulation, publication and imposition of evaluations. Empirical analysis of gatekeeping processes is easier in industries with oligopolistic structures since the oligopolists impose their (economic, political-ideological, etc.) selection criteria for shaping the mainstream so that niches for innovative productions remain small (see DiMaggio 1977, 436–452; Tschmuck 2012, 239–243; 268–271). The gatekeeper is one type of agency in cultural production; another, related to the concept of gatekeeper, is the cultural intermediary. Except in cultural markets with many players and competitors – a polypoly9 – cultural producers depend on the support of intermediaries, that is, people in the cultural field who are capable of translating between, for example, potential business sponsors and arts organizations (Martorella 1996), or indeed docents in art museums, who communicate art to an audience (Leinhardt et al., 2003). A useful and empirically applicable theory for the significance of these intermediaries is Network Theory (see chapter 10): analyses calculate network clusters (in our case cultural areas) that are connected by linking brokers to arts organizations or other stakeholders, in this case gatekeepers or intermediaries (see Jackson and Oliver 2003; Moldavanova and Akbulut-Gok 2022).

2 Main focuses in the Production of Culture Perspective

The Production of Culture Perspective developed several specific research interests. One unifying characteristic of these is the strong emphasis on empirical quantitative and qualitative data as a basis for generalized statements. Empirical evidence is solely derived from inductive data analysis, exploring the complexity of observable sociocultural events and processes and, as a result, formulate perspectives, not theories.

Changes in cultural production

An important predecessor to the Production of Culture Perspective is the study by Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, Canvases and Careers (1965; see Santoro 2008b, 42f.). This sociologically informed historical analysis of artistic production examined the shifting conditions of production, distribution and reception of the visual arts in France in the second half of the 19th century. New forms of organizing the visual arts and new social networks led to a systemic change of the production of artistic meaning and value. The turning point was the strategic decision by the impressionists to openly protest against the conservative jury of the Salon of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. Subsequently they established their own exhibition space, first the Salon des Refusés (1863) and later the Salon des Indépendents (1884). These initiatives were successful thanks to the continuous support of some art critics and art dealers. The dealers “took up the old role of entrepreneur … [and] the critics became theoreticians of art” (White and White 1965, 150); together both offered to many impressionists higher visibility, public acceptance, more sales and a steady income. The authority of the old (academic) reward system then imploded, and with the establishment of impressionism by the end of the 1880s, “the new system was fully developed and legitimate” (1965, 151). This change of the evaluative regime enabled the development of modern art. The system lasted until the 1960s, when it was replaced by the system of the art market, art fairs and affluent collectors (Zembylas 1997, Zahner 2006; Buchholz 2018).

White and White (1965) inspired many scholars of the Production of Culture Perspective, including Diana Crane (1987), who went on to analyze the development of New York’s artistic avant-gardes from the 1940s to the mid-1980s – though it should be noted that she focused on abstract expressionism, pop art, minimal art, figurative painting, photorealism, and neo-expressionism, and deliberately ignored conceptual art and performance art. She furthermore underlined the role of art galleries as places for informal encounters and network building among participants of art worlds (Crane 1987, 25ff.). Gallerists are also interested in gathering artists with a similar style because this simplifies their marketing (1987, 29ff.). Beyond that, she emphasizes the shifting of professional boundaries. Since the 1950s, many participants of New York’s avant-garde art worlds “performed more than one role: artists served as critics; critics as curators and vice versa; art editors as curators; curators as collectors; and collectors as trustees of museums and as backers of art galleries” (1987, 35). Contrary to the general image of the avant-garde as countercultural, in the 1960s, Crane observed various networks and constituencies comprising organizational patrons, professional art experts, gallerists and collectors (1987, 35f.; 44f.). Crane concludes that the Production of Culture Perspective also applies to avant-garde arts. “Art styles develop within reward systems. Groups of artists choose their own cognitive and technical goals, but they function within a support structure where they compete for symbolic and material rewards” (1987, 110).

Peterson (1990) took the advent of rock and roll music as a case study to explain the lasting commercial success of rock music throughout the following decades. As an industrial sociologist, he perceived individual creativity as a capacity that is always socially embedded in a larger industry. Therefore, his key question was what gave rise to rock and roll and why it emerged so abruptly in a short period, precisely between 1954 and 1956, when Chuck Berry, Bill Haley, Elvis Presley and Little Richard among others became the new stars of the popular music world (Peterson 1990, 97). Peterson deliberately rejects theoretical concepts like the zeitgeist, recourses to the idea of creative genius or indeed vague demographic explanations (e.g., the baby-boomers). Instead he suggests that:

In any era there is a much larger number of creative individuals than ever reach notoriety, and if some specific periods of time see the emergence of more notables, it is because there are times when the usual routinising, inhibition to innovation do not operate as systematically, allowing opportunities for innovators to emerge. (1990, 97)

One basic hypothesis in Peterson’s work is that habits and routines in organizations cause myopia and inertia, which inhibits innovation. Times of crisis and “creative destruction” through entrepreneurship – an echo of Joseph Schumpeter (see Peterson and Berger 1975, 159; Peterson 1981) – are therefore necessary to generate new impulses for innovation (see Tschmuck 2012).10 Another hypothesis central to Peterson’s analysis is that competition has positive effects on innovation and diversity (Peterson and Berger 1975, 159). Consequently, Peterson looks for empirical evidence to validate such hypotheses, and his analysis of the music industry between 1948 and 1958 is multidimensional. He makes weighty references, inter alia, to the role of licensing and collecting, to the effects of federal laws and regulations on broadcasting, to the developments in record technology and sound carriers (e.g., vinyl records), to the role of technology (e.g., portable radios and record players thanks to the invention of transistors), to market concentration – all being examples of factors that shape cultural production (see the six facets model below). In a similar way Nick Prior (2012, 405f.) asks, Why 1983? in reference to the invention of musical devices and processes (e.g., digital synthesizer, affordable drum machines, audio software packages, MIDI, CDs), which had a strong impact on the formation of DIY cultures and more generally, on the production, distribution and consumption of popular music.

Art managers as intermediaries

Richard Peterson’s paper From Impresario to Arts Administrator (1986) and Paul DiMaggio’s survey of Managers of the Arts (1987b) are examples of how to study changes among the managerial personnel of arts organizations from a sociological perspective. Arts management11 is a relatively young profession, first appearing in the mid-19th century, and it evolved as organizational environments changed over time (Peterson 1986). In his survey, DiMaggio (1987b) describes contemporaries in arts management and investigates their formal education and career paths, recruitment and forms of reward, training opportunities and professionalization. Since this survey was undertaken, many of the professional conditions for art managers have changed. Academic courses – even PhD programs on arts management – have been established in many countries around the world. The understanding of managerial responsibilities has also shifted since many large organizations have introduced dual management concepts with a formally equal position for both an artistic and an administrative director (see Cray, Inglis and Freeman 2007; Reid and Karambayya 2009). Management consultants and market researchers have entered the field to help professionals improve their performance (for a critical view of this, see Negus 2002).

Finally, many more women – but rarely people of color or people with underprivileged social backgrounds – are succeeding in occupying senior management positions in arts organizations. However, the extent of self-organization of arts managers (e.g., through professional organizations and formal membership, professional standards and extensive interchange) is still generally low – in this regard, museums are an exception. There are many reasons for this situation: First, many managers think that arts organizations (e.g., art galleries, museums, theaters, orchestras, dance companies, operas, film studios, music labels, concert agencies, publishing houses) are intrinsically very different from each other and therefore they tend to overlook their commonalities (see DiMaggio 1987b, 9). Second, the professional identities of art managers are very diverse so that some managers see themselves primarily as artists and distinguish themselves from business administrators (see Proust 2019). Third, the cultivated individualism and singularity of the fine arts (propagated since the Renaissance, see Wittkower 1961) inhibits a better understanding of cooperative and collective professional performance, good governance and ethics (see Wolff 1993 [1981]).

Classification of cultural production

In Europe, the court system had a long historical tradition, and from the 16th century onwards systematically promoted arts, paving the way for the development of certain art forms as part of the nobility’s cultural identity. The historical situation in the United States was different because the court system was never established and also because the urbanization and the foundation of the first arts organizations took place later, in the second half of the 19th century. Paul DiMaggio (1982a, 1982b, 1992) analyzed the fabrication of highbrow culture in North America by showing how organizational policies were successful in segregating artistic domains and establishing cultural classifications. He focused on the role of social and economic elites in Boston after the Civil War. By taking control of a few nonprofit cultural organizations (through establishing and participating in boards of trustees, engaging particular individuals in leading positions, etc.) members of Boston’s elites initiated a purification of arts from the 1870s onwards, separating high from low, American from foreign, and white Anglo-Saxon protestants from immigrant and black culture (see Levine 1990, Lena 2019). In the early 20th century, the institutionalization of high arts was extended by the foundation of national umbrella organizations, which bundled together organizational interests, and by private foundations, whose systematic support of a few arts organizations determined merit and public value. DiMaggio (1987a; 1992) is unequivocal that this cultural segregation through a classification system was brought about by cultural hegemony, which served to legitimize established social asymmetries and racism. In other words, not only production but also consumption is socially organized according to social stratification and cultural differentiation (DiMaggio 1987a, 446ff.; see Lena and Peterson 2008). However, this observation is not static, since DiMaggio (1991b, 141ff.) acknowledges that in his time, the so-called late modern or postmodern era, there is an erosion of the segregation of high and popular culture (for more on Peterson’s omnivore thesis 1992, see next section). The reasons are indeed varied: the spread of higher education, increased social mobility, growing cultural heterogeneity, the consecration of artistic forms that were previously considered popular and commercial (e.g., jazz, art photography, film d’auteur), the broad dissemination of some genres of popular music (e.g., rock), the economic constraints for art organizations (e.g., the so-called cost disease), and a shifting of interest among economic elites promoting exclusivity (e.g., from classical music to private art collections) (see also Boltanski and Esquerre 2020).

Cultural consumption as the other side of the coin

Although the Production of Culture Perspective focuses on the production and distribution of cultural goods and services, audiences also have a significant influence on the production site. Peterson (1997; see Lena 2012) ascribes audiences an active role in the meaning and value-creating process, and speaks therefore of “autoproduction” in order to explore:

how that idea [cultural production] moved from a focus on the institutionalized culture industry worlds to the autoproduction that takes place as individuals and collectivities adopt expressive symbols and, in recombining them, make them the source of their identity. (Peterson 2000, 225)

The erosion of the strict segregation between high and popular culture already points to the significance of changes among audiences and consumer behavior. With critical reference to Bourdieu’s seminal work (1984) on cultural tastes and preferences, Peterson and others have investigated the tastes and cultural practices of a highly educated, liberal and mobile milieu living in North American cities and developed the concept of cultural omnivorousness in contrast to Bourdieu’s homology concept. Using representative quantitative data gathered over many years on cultural consumption in the United States, Peterson (1992) and Peterson and Kren (1996) observed a broad spectrum of cultural interests and preferences that led to the conclusion that this population segment – well-educated, prosperous urban people with a liberal lifestyle and a pluralistic value orientation – is less interested in exclusive cultural practices that distinguish them from other social classes with a lower status (for empirical analyses of European societies, see van Eijck 2000). This omnivore thesis is distinct from a univore taste that, according to Peterson, is found mainly in lower social classes. Cultural omnivorousness is multifactorial and depends not only on education, but also on cosmopolitanism (Regev 2007), place of residence (Shani 2021), membership in socioeconomic networks (Meuleman 2021) and age (Ma 2021). Despite recent doubt about the stability of omnivorousness among cultural consumers (Rossman and Peterson 2015), this thesis has become an integral part of the analysis of consumption that completes the production perspective.

Correlating several factors of cultural production:

the six – or ten – facets model

From the outset of his scholarly work on cultural industries, Peterson’s concern was to explain change (Peterson and Berger 1971; 1975). He was particularly interested in industrial conditions (e.g., concentration, competition), with a focus on the popular music industry as he had already gathered systematic data mostly related to the record industry (Peterson and Berger 1975, 159ff.). He subsequently identified a variety of structuring aspects – Peterson also spoke of “constraints” (1982), “factors” (1990), and of “facets” (Peterson and Anand 2004) – that regularly influence not only forms and styles, prices and production numbers of cultural products, but also more generally cultural diversity, innovation and therefore cultural change (Peterson 1997; Dowd 2004). These six facets include:

-

A legal and political framework: e.g., copyright and patent law, antitrust law, cultural and media policies, but also constitutional rights related to freedom of artistic expression12

-

Technological changes: e.g., artistic materials and instruments; printing, recording, and audiovisual technologies; broadcasting and TV; digitization, internet and artificial intelligence

-

Industry structure: e.g., size, capitalization and financial conditions; interconnections between production and distribution chains

-

Organizational structure: e.g., hierarchies and formalization of decision-making processes; cooperation between internal units; relations to other companies. Organizational structure is divided in three substructures: (a) bureaucratic with a hierarchical chain of command from top to bottom; (b) entrepreneurial based on short-term projects and fluid teamwork, without any manifest hierarchy; and c) variegated form tries to keep central control of the bureaucratic structure, but is combined with the free-wheeling creativity of short-term services,

-

Markets: e.g., monopolies, oligopolies or polypolies; contracts with producers; supply-side analysis of demand; marketing strategies; distribution processes; digital platforms

-

Occupational roles in the context of organizations: e.g., professionalization, functional differentiation and specialization, forms of collaboration, career paths in relation to various intersectional aspects; regimes of competence, unions.

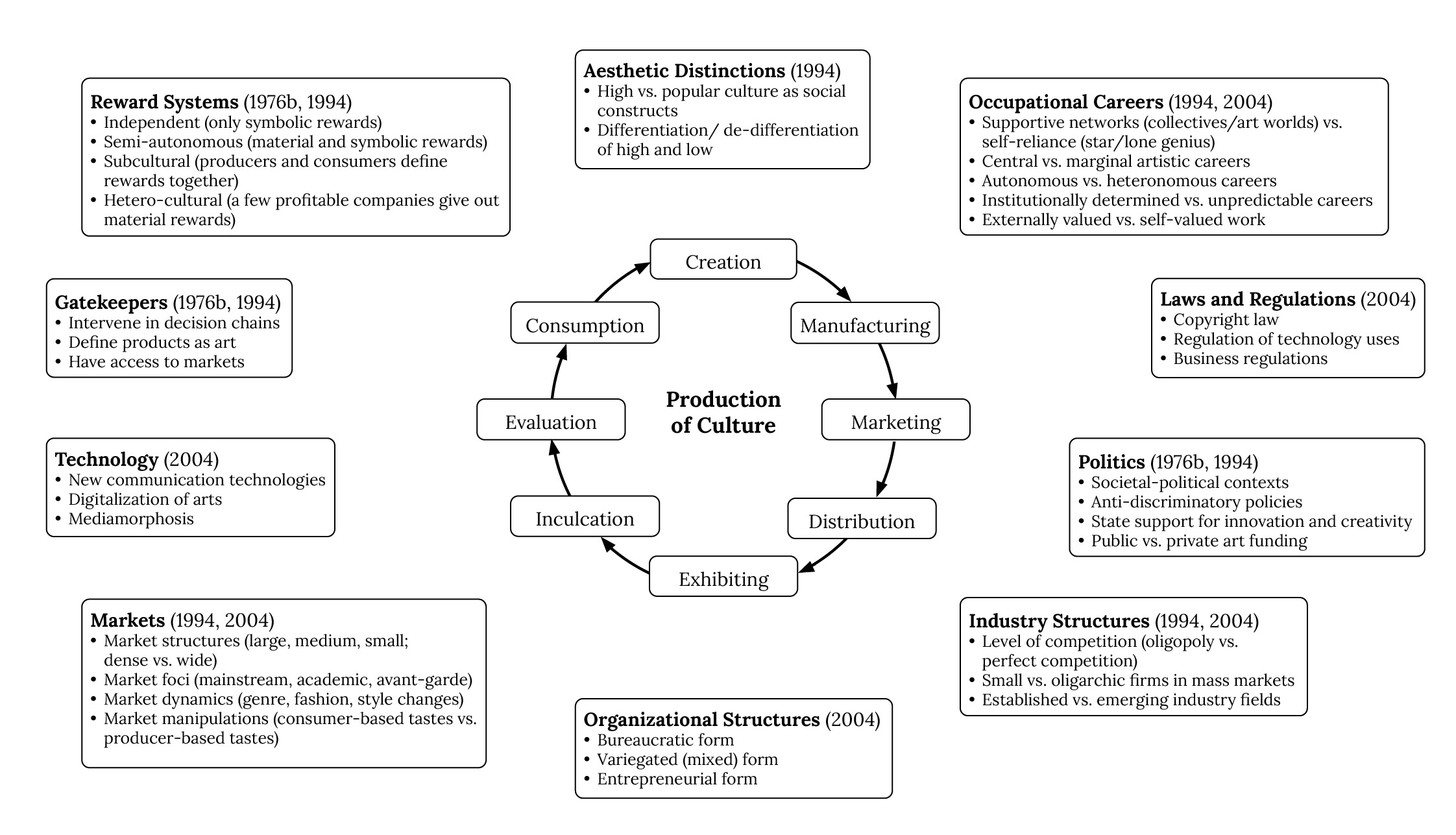

Figure 4 Ten Facets of the Production of Culture (see Peterson 1976b, 1994; Peterson and Anand 2004). Note: the year in the figure is the year of publication.

Peterson (1985, 64) himself does not claim to be exhaustive when providing these six facets, and because his model is inductively generated, these facets can be extended. Indeed, a careful reading of his publications offers a larger number of facets. In 1976 (revised in 1994), Peterson, following Crane’s works, introduced the significance of reward systems, gatekeepers and politics. In 1994 (revised again in 2004), he stressed the significance of aesthetic distinctions, occupational careers, markets and industry structures as additional facets, and in 2004, he added technology, organizational structures together with laws and regulations. This development prompts us not to speak of a six-facet model, but a ten-facet model (see figure 4).

It is evident that a more in-depth examination of each facet is only possible with the appropriate interdisciplinary competence (e.g., a competence in legal studies and policy analysis, in the history of media and technology, an in-depth knowledge of particular industries and their local structures, in organizational research and management studies, in cultural economics, in occupational sociology and communities of practice; see Hirsch 1978, 325–330). Therefore, this kind of industrial and organizational analysis is quite challenging and requires interdisciplinary teamwork.

To sum up, the Production of Culture Perspective is characterized by these central features:

-

It is an empirical and inductive sociological approach with strong links to sociology of industries, organizations and occupations. It aims to explain the emergence and change of cultural goods, and in doing so it transcends deterministic views of cultural production and consumption.

-

A broad definition of the term production includes consumption (Peterson, 1976b, 10). Peterson (1986, 1990) frequently analyzed how consumption and production affect each other, for example, how images of consumption shape decisions of cultural producers and arts managers. A strict production/consumption dichotomy is therefore called into question.

-

Neither cultural production nor consumption is spontaneous; they are also not the outcome of rational planning. Multiple institutions are involved in shaping cultural production and consumption, yet without determining them.

-

Cultural industries consist of clusters of cooperative activities. A number of professionals intervene, mediate and contribute to cultural production and value creation. Their mediation is constitutive for acts of consumption as well.

-

The evaluation and valorization of cultural production (i.e., various reward systems) usually happen within contexts where arts and culture are produced, presented, discussed, mediated, sold and consumed. These processes influence the content and style of new cultural products.

-

The cultural industries are not disconnected from social and political ideologies. Therefore, non-artistic criteria (e.g., moral, political, economic criteria) may also play a crucial role in the classification and valorization of cultural production.

3 Critique of the Production of Culture Perspective

Paul DiMaggio (2000, 130) comments retrospectively that the Production of Culture Perspective “has received relatively little criticism” and this might be “a result of the open endedness of the perspective and its consequent tendency to absorb new ideas and problems.” Peterson himself advises researchers “to avoid clinging to any single level of analysis” (Peterson 1994, 180–182) and to view the emphasis on organizational factors and markets as “heuristic … [and not as] an empirical given” (DiMaggio 2000, 130). Notwithstanding, a general critique finds fault with the strong focus on institutional and organizational analysis and in turn a neglect of the cultural objects and their sociocultural contexts. This critique took several forms.

Coming from an interpretative sociological approach and acknowledging the role of consumers as co-creators of cultural meanings, Wendy Griswold (2004, 10, 12) investigates how cultural meaning is formed and how it changes in relation to different social contexts (in theater, Griswold 1986; in fiction, Griswold 1981, 1987). She defines cultural objects as “shared significance embodies in form” (2004, 13) and ascribes receivers (consumers) the ability to create and adapt meaning through interpretative frameworks and horizons of expectations (2004, 92, 95f.). In doing so, she refers to “social minds,” which people “as members of particular groups and categories” share (2004, 92). Meaning is, however, not a subjective, but a social outcome of a dynamic relation between, first, creators, who are usually embedded in organizational arrangements, second, receivers, who are embedded in social worlds and, third, cultural objects that afford aesthetic experience and meaning-making. Griswold (2004, 21ff.) made a significant contribution to analyzing the formation of cultural meaning by integrating cultural objects into the meaning-making process. She sees her own contribution as an extension of the Production of Culture Perspective13 when she writes that “our definition of cultural objects is much broader [than the understanding of the Production of Culture Perspective], embracing concepts and ideas” (2004, 89). Victoria Alexander (2021, 50f.) adopted and modified Griswold’s Cultural Diamond by ascribing distributors (cultural intermediaries) a central role in mediating between creators, consumers, artworks and society (see chapter 10).

Similarly, Keith Negus points to the necessity of supplementing the Production of Culture Perspective with a perspective on the cultures of production, by which he means an analytical expansion to include the meaning of cultural products. With reference to Raymond Williams and British Cultural Studies, Negus argues that cultural production involves a “whole way of life,” arguing that “we need to do more than understand culture as a ‘product’ …. We need to understand the meanings that are given to both the ‘product’ and the practices through which the product is made” (Negus 1997, 101; see Negus 1996, 59ff.).14 In a similar vein, Harris Friedberg (2001, 156f.) suggests that it was not only various facets of the music industry that brought about musical developments, but also that there is evidence “that rock and roll itself changed the industry.” Ron Eyerman and Magnus Ring (1998, 281; see de la Fuente 2007) follow this critique when they write that the focus on “the social organization of cultural production has been reluctant to consider … the content and meaning of an artifact.”

There are plenty of arguments to counter these criticisms. First, it is worth noting that the primary goal of the Production of Culture Perspective was not to explain cultural meaning, but to shed light on the social and organizational factors that produce and shape cultural products and their content (DiMaggio 2000, 131). Peterson himself (1994, 184f.) acknowledges the limitations of the Production of Culture Perspective, which runs “the risk of eliminating ‘culture’ from the sociology of culture,” yet he also reminds us that researchers working from the other side “who focus on the content of cultural products run the risk of focusing on critical concerns and taking the ‘sociology’ out.” Second, one should take into account the constructivist approach of the Production of Culture Perspective regarding meaning-making processes (see Bryson 2000; Crane 1987; Fine 2003; Grazian 2004; Hirsch 1978; Peterson 1997). Clearly Peterson posits that meaning is not incorporated into symbolic products, but emerges from the conditions of their production, presentation, mediation and consumption (Peterson and Anand 2004, 327; Santoro 2008b, 51). Moreover, he focuses on “situations where the manipulation of [cultural] symbols is a byproduct rather than the goal of collective activity” (Peterson 1994, 164). Therefore, as Vera Zolberg (2000, 160) rightly remarks, the Production of Culture Perspective “envisaged the arts less as objects [which is common in humanities], and more as process.”

Another objection, first formulated by Janet Wolff (1993 [1981], 31), refers to a non-normative attitude and the lack of a critical perspective on cultural production. This view is also shared by David Hesmondhalgh (2002, 36), who believes that the Production of Culture Perspective appears “uninterested in even asking such questions” relating to power, domination and hegemony. Paul du Gay (2013, 10) argues in a comparable direction: the study of the production and consumption of culture should be seen in the context of what he calls a “circuit of culture,” in which issues of cultural meaning, regulation and normativity; representation; and identity must be taken into account (see chapter 10 in this book). This critique is to some extent justified, since the Production of Culture Perspective did not analyze cultural industries from a theoretical or a political economy perspective (see Mosco 2012).

In the words of Peterson (1994, 185), it tries to avoid “the unanswerable questions about the causal links between society and culture.” However, the research focus on gatekeeping processes, reward systems and cultural classification systems indicates a clear attention to power relations and normative issues.

Endnotes

-

In this context, the term reflection theory refers to the idea that trans-subjective features – Hegel was referring to the world spirit (Weltgeist), Marx to social structures and class struggles – shape individual subjectivity, as well as artistic content.↩︎

-

Although we refer to the situation in the United States, it is worth noting that in the 1950s and 1960s there were sociologists of arts in Europe who were also working empirically, such as Franco Ferrarotti in Italy, Raymonde Moulin in France, Alphons Silbermann in Germany or Kurt Blaukopf in Austria.↩︎

-

Contingency runs contrary to the idea of determining forces, for example, of zeitgeist, value orientations, structures, class interests, etc.↩︎

-

In preparation for the conference Euro-Pop: The Production and Consumption of a European Culture in 2009 in Italy, Richard Peterson delivered a paper outlining the Production of Culture Perspective; see https://codeandculture.wordpress.com/2009/08/26/production-of-culture/ [accessed on Dec. 19, 2021]↩︎

-

In fact, most members of the Production of Culture Perspective were in contact with Howard Becker (see for example, DiMaggio and Hirsch 1976, 74f.). In later interviews both Becker and Peterson acknowledge the proximity of their work (Santoro 2008b, 48).↩︎

-

Representatives of British Cultural Studies also shared this open and pluralistic understanding of arts.↩︎

-

Elisabeth Bird (1979, 43) writes that “the premise of aesthetic neutrality is … impossible to maintain, because the historical process itself assigns a value.” Peterson would probably not deny this and would add that the sociological task is to explain how value ascriptions take place and how evaluative processes are shaped by institutional and organizational settings.↩︎

-

Paul Hirsch (1978, 315f.) distinguishes production from distribution. This distinction is justified for analytical reasons, yet all researchers associated with the Production of Culture Perspective underline the interrelation and interdependence of both domains.↩︎

-

Poly means many, and polypoly is used in contrast to monopoly and oligopoly. We deliberately do not use the more common term free market for polypoly, because it is associated with a specific interpretation of markets and social relations.↩︎

-

Peterson (e.g., in Peterson and Anand 2004) understands innovation in much the same way as Schumpeter, in other words, as the ability to create economic value from a new product or service (market innovation). However, he also considers management (e.g., new forms of work organization and coordination) and institutional innovation (e.g., new organizations that offer new services, which in turn create new markets) (see Brooks 1982).↩︎

-

Arts management stands for several tasks in arts organizations that are sometimes performed by various individuals and teams. Arts management includes programming and production management, artistic and organizational development, strategic management, human resource management, accounting, controlling and finances, management of facility and technical services, marketing, audience development, hospitality management, public relations and communication.↩︎

-

Peterson mentioned only the legal framework, but we have added policies to refer to other countries (e.g., European countries) and artistic domains (e.g., opera, cultural archives), where public funding plays a stronger role than in North America.↩︎

-

In the acknowledgement of Cultures and Societies in a Changing World, Griswold (2004, xviii) names Richard Peterson as one of her teachers.↩︎

-

Diana Crane (1992; see Peterson 1994; 2000) compares the British Cultural Studies with the Production of Culture Perspective and identifies many differences.↩︎