A Conversation with Nikolaus Urbanek and Michelle Ziegler

Jan Brocza, Reinhold Friedl, Thomas Grill, Katharina Klement, Christian Tschinkel and Anatol Wetzer

How to cite

How to cite

Note: The conversation reproduced below took place on 12 December 2022, at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna; some participants were connected via video conferencing software. The transcription of the conversation, which was conducted in German, was edited by all participants and subsequently translated into English.

The reference of the conversation was the performance of the complete electroacoustic works of Iannis Xenakis in the context of the symposium Xenakis 2022: Back to the Roots, which took place in May 2022 at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna.

19 May 2022, mdw Klangtheater: Iannis Xenakis – Complete Electroacoustic Works I

Diamorphoses (stereo) – Sound projection: Arthur Fussy

Concret PH (4 channels) – Sound projection: Jan Brocza

Orient-Occident (4 channels) – Sound projection: Madeleine Fremuth

Bohor (8 channels) – Sound projection: Katharina Klement

Hibiki Hana Ma (8 channels) – Sound projection: Christian Tschinkel

Polytope de Cluny (8 channels) – Sound projection: Pierre Carré

20 May 2022, mdw Klangtheater: Iannis Xenakis – Complete Electroacoustic Works II

Mycènes alpha – Sound projection: Angélica Castelló

Voyage absolu des Unari vers Andromède – Sound projection: Elizaveta Trukhanova

S.709 – Sound projection: Reinhold Friedl

La Légende d’Eer (8 channels) – Sound projection: Wolfgang Musil

21 May 2022, mdw Klangtheater: Iannis Xenakis – Complete Electroacoustic Works III

Taurhiphanie (mono) – Sound projection: Jonas Hammerer

Gendy 3 (stereo) – Sound projection: Anatol Wetzer

Persepolis (8 channels) – Sound projection: Thomas Grill

Nikolaus Urbanek (NU): I was very fascinated to hear the sonic realisations of all of Iannis Xenakis’s electroacoustic works on three evenings at the Klangtheater and to gain insight into the different interpretations. I would like to ask you how you conceived your respective interpretations.

Katharina Klement (KK): I interpreted the piece Bohor (1962) at the symposium. I chose this eight-channel piece because it was already familiar to me to a certain extent. I found it very interesting because it’s about a sound mass, and interestingly I have the same cross arrangement of stereo tracks in my own works. Thanks to a lot of research and an unpublished text of yours, Reinhold, I got a lot of information about this piece, which was very important for me and definitely influenced my interpretation (cf. Friedl 2019). I can explain this in detail later. Bohor has held a certain mystery for me. This title appealed to me. And I performed it twice: once at the Klangtheater and once at the Belvedere 21 museum (aka 21er Haus) at Wiener Festwochen on 18th of June 2022.

Thomas Grill (TG): I realised the piece Persepolis (1971). I was familiar with the piece from a performance by Daniel Teige in the big hall of the Konzerthaus Vienna about 15 years ago. It was a formative performance for me, extremely loud and unusually harsh for the Konzerthaus. They really sat there with the volume meter and pushed against the gain threshold. Nevertheless, I found the piece extremely good, even in this loudness, and I resolved to perform it myself one day. Now the right opportunity had finally come, however, I chose a completely different approach and oriented myself more on the original performance in the ruins of Persepolis, where it was set up almost like an installation with far more than eight loudspeakers. Xenakis chose an approach very different from a concert performance.

Anatol Wetzer (AW): I played Gendy 3 (1991), a stereo piece. I approached it with very little prior knowledge and mainly focused on the different sonic layers. My idea was to use the four speakers in the room, which were not part of the standard hemisphere, and the top circle of the hemisphere. I changed the projection depending on the section and the timbre.

TG: And why did you choose that piece?

AW: Jonas [Hammerer] had two pieces. I listened to both and liked Gendy 3, partly because it was so inaccessible and sounded hermetic due to the computer composition.

Christian Tschinkel (CT): Thomas Grill suggested a few pieces for interpretation, especially Hibiki Hana Ma (1970). Since I already owned the new 5CD box with the complete electroacoustic works of Xenakis, I was able to listen to each of the pieces in question. I found Hibiki Hana Ma quite challenging – sonically as well as structurally. With a certain curiosity, I agreed to interpret it and face the chaotic texture of this piece.

Reinhold Friedl (RF): I played S.709 (1994). It was the last piece; nobody had chosen it. And this monophonic product of a computer algorithm is also Xenakis’s last electroacoustic music. Raw and harsh, someone called it a “bitter old-age work”. I wanted to support this character and projected it from only one loudspeaker – directly in the zenith of the hemisphere, right over the heads of the audience – purely mono. Absurdly, the result was a spatial effect. One had the impression of a moving sound cloud, probably because individual frequency bands are reflected differently in space. It is an extreme interpretation: a non-interpretation so to speak, in the performance I did nothing other than to minimally adjust the volume of the single speaker.

Jan Brocza (JB): I performed Concret PH (1958). It was a piece that I was familiar with, that I found very beautiful, and that was also very manageable because at first I wasn’t sure if I was confident about it. It was a good decision. I like the piece very much. I had the four-channel version from the GRM (Groupe de recherches musicales) archive. Since it doesn’t have giant dynamics or a big build-up, I tried to keep it rather quiet in space and not make huge movements. After about 40 seconds, there’s a part where a little more bass frequencies come in, so I tried to open up the space a little more. But my interpretation was rather minimal.

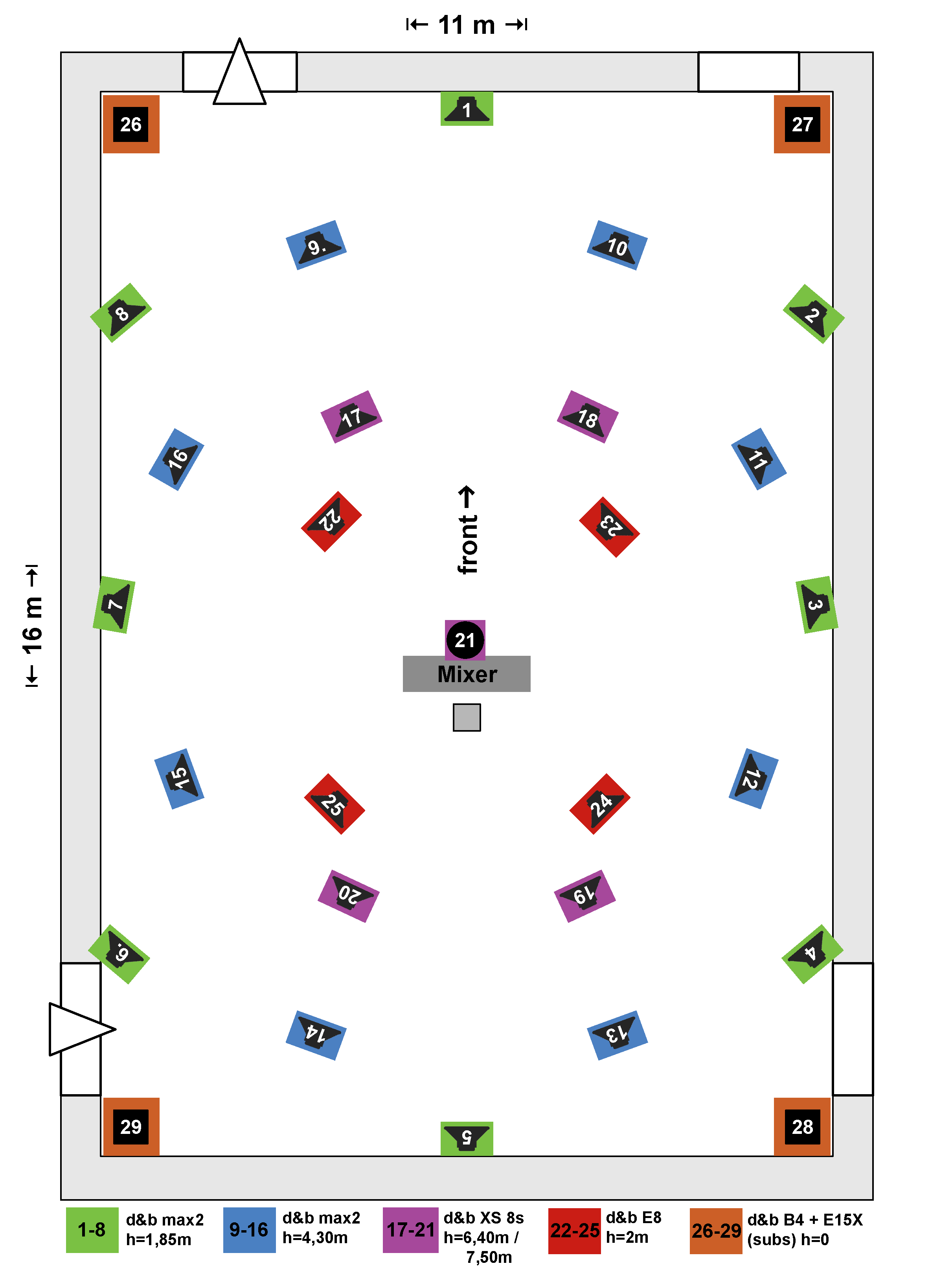

Figure 12.1 Loudspeaker positions in the Klangtheater. General plan by Thomas Grill, 2024.

RF: Opening up the space means spreading the sound on the speakers wider?

JB: I made the sound of the subwoofers and the speakers on the ceiling a little louder and took the inner ring (the four speakers positioned around the mixer) down a little bit at the same time. That’s what I mean when I say I opened up the room a little bit in that moment, in order to give the audience the feeling of being more immersed.

NU: I would like to go back to the subject of the special space of the performances, the new Klangtheater at the mdw. I think everyone knows the Klangtheater very well by now?

TG: The Klangtheater is still new, we are always discovering new facets of the space. But, of course, we had already had intensive contact as users in the Programme in Electroacoustic and Experimental Music (ELAK) and had performed many pieces here. When one gets into the intricacies of an interpretation, new questions always arise, such as how to map something on the mixer so that it is expressively playable during the performance, because there are so many options.

NU: And how was the technology set up for the Xenakis performance?

TG: We basically used the permanently installed periphonic sound system, 21 loudspeakers in a hemisphere. There is an eight-speaker ring at ear level, numbered clockwise (1–8). A second ring is at about four metres and is numbered the same way (9–16) and a third ring with four speakers is at about six and a half metres (17–20). Finally, we have loudspeaker number 21 located seven and a half metres above the mixing console just below the ceiling, the “Reinhold speaker” as we have called it since the symposium. In addition, in order to project the sound in the opposite direction, we had four loudspeakers on tripods set up around the central mixing console and facing the walls at an angle of about 45 degrees. Anatol used that, for example. Four subwoofers in the corners of the room completed the sound reinforcement.

NU: I would be very interested to know how much the space itself influenced interpretative decisions, whether, for example, certain changes were still made during the performance in order to be able to react spontaneously to the space, to the presence of the audience. Maybe we could start with Katharina because you said you performed Bohor in two different places.

KK: Bohor is an eight-channel piece – more precisely, there are four stereo tracks arranged crosswise. In the Klangtheater, I have assigned these to the three speaker rings accordingly. If there is channel seven in one corner, then it is there on all the three levels, and channel eight is in the opposite corner on all three levels. I then mainly controlled the sound between these three levels, but also the ratios of the four stereo tracks to each other. In comparison, it was easier at Belvedere 21 with only eight speakers. There I concentrated on the volume ratios of the individual tracks in the interpretation, which was an experiment for me: In the piece, this sound mass should actually be present from the beginning, with an additional large crescendo. And I decided to play that in contradiction to the historical sources. At the beginning, I faded in each track very slowly because it was important to me to be able to listen more closely to the details of the individual tracks. That worked quite well, I think. I did that both times, in the Klangtheater and at the Belvedere 21 museum.

TG: I’m happy to continue because I had the same situation as Katharina. I performed Persepolis twice in completely different places: in the Klangtheater and at the Belvedere 21. The Klangtheater is acoustically very dry; sound emitted by a loudspeaker is very direct, that is to say, not mediated by reflections of the room: A really direct access to the ear. In the 21er Haus, it’s the opposite: There are glass walls that reflect strongly and repeatedly. The sound is much less direct there. That is why I conceived two completely different interpretations. In the 21er Haus it was more like the one by Daniel Teige, with great volume, really big, in order to try out a canonic interpretation. I aimed for the opposite of this massiveness in the Klangtheater, where I tried to create a more attentive listening situation but, nevertheless, respect Xenakis’s original performance situation. In the plans of the acoustic setting in the ruins of Persepolis, groups of about eight loudspeakers were placed in several parts for over 50 loudspeakers. The audience could stroll between the individual groups – in other words, it was like an installation, a walk-in performance situation. For my performance method in the Klangtheater, I set myself the task – since people are all sitting in fixed positions – of re-creating these changing perspectives for the audience. During the hour-long piece, I tried to give different perspectives on the sound material, to let it come from different directions, to set different volumes for different materials, and thus to simulate the walking around. Like Katharina, I did not start massively either, but realised more of a walking through the sound material, as if one approached the field of ruins, went there, walked around inside and finally left again. That is certainly very different from the usual canonical performances of this piece.

RF: Okay, got it… [laughs]. We had a heated discussion right after the performance, I was pretty irritated and asked: “Is that supposed to be Persepolis?” Now I understand the approach, and it is indeed an interesting one, simulating a moving listener, so to speak.

Figure 12.2 Blueprint with positions of the loudspeakers (in red) for Persepolis. Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 27-4, p. 4.

TG: It appeared to me that being stuck in one place is unsatisfying given the situation in the ruins in Persepolis, where so many potential perspectives could open up, and I thought this had to be realised somehow. There were several listening rooms with grouped speakers. That’s why one can assume that in this acoustic scenario, different sound sources were strongly mixed. There must have also been run-time differences due to the different distances to the loudspeakers. A static interpretation in the Klangtheater would not have reflected this at all.

RF: The speakers were apparently distributed pretty asymmetrically in Persepolis, probably just by trial and error?

TG: Yes, that is to be assumed. It is the opposite of a clearly defined surround situation with eight channels.

CT: For Hibiki Hana Ma I started from the given grouping of the eight tracks already predetermined by the speaker rings in the Klangtheater. I could intervene in each group, i.e., despite the fixed layout as a multi-channel piece, I always had an additional subtle weighting in space from bottom to top, but also the possibility to intervene in individual eight-channel groups. What was important to me was a full, rich sound – a good sound quality – with simultaneous amplification of certain phenomena: for example, that the sudden wooden knocking clearly comes from an unexpected direction, without being covered by other sounds – so to speak, a peeling out of distinctive materials. I did not provide excessive sound movements, only for the glissandi, which in my opinion were allowed to whiz through the room a bit.

NU: Now we have heard a lot about the consideration of the spatial situation of the performance. Are there also other aspects that were particularly important to you in your interpretation, for example of a structural nature or regarding the choice of volume?

AW: Gendy 3 is very strict and straightforward but has these sudden timbre changes, those moments where a frequency comes in or disappears in a very audible way. I used them for orientation and thought very carefully in advance about how to emphasise those moments of change. I listened to the piece very often and defined these sections for myself. I then implemented this quite precisely in the Klangtheater and changed practically nothing during the performance. It was only after the concert that I wondered whether it hadn’t been too quiet and therefore missing a few details.

NU: May I ask a quick question back here? For Anatol, the orientation to the sound structure of the work was, if I may say so, important for coordinating the interpretation. Thomas, with you the premiere situation and its spatial conditions came into play, which rather contradicted a ‘canonical performance’.

TG: I also took my cues from the material. There are ten different textural materials in Persepolis. Each of the eight channels has the same ten materials in a different order and it makes a big difference whether you have bright and direct material at ear level, for example, or on the higher speaker. I have decided carefully beforehand where to position which material, especially in terms of height and distance, partly because the front speakers are further away than the side ones – the “rings” aren’t rings, but ellipses. That is also a parameter. It is a mesh of decisions that have to be made. And volume is also an issue, of course; you cannot readjust it greatly during the performance due to the stationary nature. Setting the volume at the beginning is the hardest thing, I think. If you decide to play Persepolis at full volume, for example, you stick with it. After all, the piece lasts almost an hour and is very monolithic.

CT: I started with a little Internet research about Hibiki Hana Ma. Besides the key data, it is always important for me to know what a title means. I used the online translator and found out that the Japanese characters 響き – 花 – 間 mean ‘reverberation-flower-interval’. Well, but I did not know how this could affect my mix in the Klangtheater. What was more influential was the fact that this piece was composed by Xenakis for the 1970 World’s Fair in Osaka, where it was performed in a multimedia show including mirrors, light and laser – as so often with Xenakis a spectacle linked to great architecture.

Since I did not want to play the piece quietly, I felt confirmed by the word ‘spectacle’. To my taste, there was still room for improvement in some places, although the dryness of the Klangtheater encouraged this immense immediacy and directness, which is why I remained reasonably within the limits. For I am aware that loudspeakers – to use Stockhausen’s words – are weapons, especially at head height. In addition, I personally find the highs in Xenakis always challenging, not to say problematic. You always feel under power while listening.

I had rehearsed the piece relatively loud, but in the concert situation I was a little unsettled by “more careful”, i.e., less loud interpretations, and asked myself whether I should join in. But actually, it was by then already clear to me that I would stand by my rehearsed interpretation as a contrast to the others, and in a conversation shortly beforehand, Reinhold also confirmed my intention to do so. I think it suits me to play this music in this way, and I think it also corresponds with Xenakis’s idea. I know listening to the performance of so many works in one evening is a challenge for the audience, but Hibiki Hana Ma needs a monumental interpretation.

NU: For a better understanding, I would like to ask how you solved the disproportionate relationship between the number of channels of some the pieces on the existing data carriers and the number of loudspeakers in the Klangtheater. Was it also necessary to adjust anything sonically?

JB: Concret PH was premiered in 1958 in the Philips Pavilion at the World’s Fair in Brussels with a lot of loudspeakers, several hundred. So, I thought I would definitely use all the loudspeakers in the Klangtheater. Since the piece is not long and has no significant sections, my idea was to keep it rather static, to be very subtle with it, and to project it to the whole room all the time. The piece consists entirely of the finest snippets of recordings of glowing coal. And as I said before, at about second 40 there are some deeper coal shards that come in. That’s where I wanted the audience to get the feeling that something is happening by spreading out the spatial sound image. Just before the end, there are a couple of sharp spots, and since we had generally found beforehand that many of the pieces can be very intense in the high frequencies, I tried to balance that spot out a bit. Those were the strongest interventions.

TG: To lower the high frequencies, did you use a filter or did you just adjust the volume accordingly?

JB: I did not filter. I noticed a passage in this four-channel version that was just a bit more aggressive, and I knew that I had to go down two to three decibels there. I remember not noticing that at all in the other versions but listening to the four-channel version at the Klangtheater, it became more obvious. I made the decision on the spot, I had not thought about it before. If I had played the whole piece at the same volume, there would have been passages where it would have hurt a little bit. I wanted to avoid that because the programme was pretty long. I played second and thought that it wasn’t necessary to challenge everyone right away.

TG: In principle, you can say that you really have to listen to the material on site. It sounds different with every speaker system. And even if Martin Wurmnest mixed it on his loudspeakers to the best of his knowledge, that doesn’t mean that it would sound perfect here: The loudspeakers are different, the distances are different, and so on. Also, the variety of speakers and their placement sometimes leads to phasing effects that can emphasise or cut certain frequencies. There is also a difference between the rehearsal situation and the performance situation. Not only in instrumental music, but in the Klangtheater, too, one has to consider that the room becomes much drier with an audience, so you need more volume. I would say at least three to four decibels can be added. These are decisions, as Jan said, that can and must often only be made during the performance.

JB: Exactly. I was also satisfied, although other people thought it could have been louder. Maybe I’m personally more sensitive to volume, but I think it was a good fit.

TG: Reinhold? You’ve already said almost everything about your interpretation…

RF: Yes, but we are now approaching some classic questions about interpretation. The one thing you hinted at, Thomas, is that any electroacoustic realisation or projection is always an instrumental representation, which depends on the playing situation itself. For example, the sound in a room with an audience becomes not only quieter but also more directional and drier. This means you have to be familiar with your ‘instrument’ and must have practiced so that you can respond properly. This situation is very similar to playing an instrument in a concert hall.

The second question is: How do I implement an analytical insight musically? I remember that the pianist Wilhelm Backhaus did not emphasise the themes of the fugues in the Well-Tempered Clavier, because he assumed everyone knew them anyway. Charles Rosen, pianist and musicologist, discussed this question explicitly: How does an analysis change my interpretation? In our discussion today, I think we have a somewhat naive view: “I make an analysis and then play the result”. For Backhaus this would have been too pedagogical.

Katharina on the other hand, did not start from an analysis but from an extra-musical idea, namely: “I want to introduce the sound material slowly”. This ignores the fidelity to the work and is actually a bit cheeky towards the composer.

KK: Well, if you address that directly, I had the most respect or fear of you at the beginning of the project, Reinhold. You were at the first rehearsal in the Klangtheater and I asked: “Well, these eight tracks in Bohor, they actually go through relatively invariably and only distort at some point”. And you said: “Yes, that is what is on the tape and, of course, Xenakis wanted it that way, the material is meant to go through from beginning to end”. I had thought that maybe that’s just sound material and then I can play with it in the interpretation [laughs]. I then decided that I didn’t want to hear everything from the beginning. Even more so, I think one track starts off pretty bumpy. It almost sounds like a technical error.

Since you mention the Well-Tempered Clavier: I thought, I moved so far away from this classical interpretation, with which I already had problems in my pianist days. I now just do what I want, with Xenakis, too. I do not want to play a classical interpretation, where I’m told to keep this faithfulness to the work. I think a piece simply has to be understandable and sound good – that is, the way I think it sounds good. I think that was the right way to do it. And yes, that worked quite well.

RF: Your idea was not only to make it sound good, your idea was to introduce the material slowly to the listener. That means accommodating the listener, developing a listener-friendly dramaturgy?

KK: Yes, absolutely. I felt like you don’t really hear anything because the tracks are relatively similar. They’re all metal sounds, rich in detail, and I thought you could just introduce them successively and then you would have 15 minutes to listen to them at the same time anyway. That was my plan. So, I used the first five minutes of those 20 minutes to introduce the voices one by one. Which I’m sure, if you look into the historical sources, is not written anywhere.

RF: Yes, you took that liberty…

TG: It’s basically the same with Persepolis. I just took it as material because there are ten textures lined up in blocks more or less unedited. There is a sequence, just as the synchronicity between the tracks is, of course, already composed, but the material is block-like. From our point of view, working very much with material, one would say it’s almost untreated. In this respect, I did not think much about having to treat it faithfully in the performance because it comes as material. Of course, you cannot decide to start a track later, as that would throw the arrangement out of whack. And you cannot go wild with the volume because the balance would be disturbed. But if you think about the fact that this has to be blocky now, and that this should reflect the texture as such, you’re still in the realm of faithfulness to the work. How you put things into perspective or how you let them change in volume: I think you have a certain freedom there. Even if you look at the original production of Persepolis: There were seven groups of about eight loudspeakers each somehow standing next to each other in uncovered ruins. This set-up makes an absolute volume or fixed ratio virtually impossible. Canonical performances are not the measure of all things.

NU: I find it very, very exciting that we are now thinking about concepts such as freedom or faithfulness to the original, that we are already considering ideas of the premiere scenario, that is, relatively ancient ideas of an authentic performance practice/a historically informed performance practice. But we are also considering not only the extent to which the history of interpretation, which can also move away from the premiere situation, plays a role, but also questions of analysis. Reinhold, I would be very interested to know what, in your mind, falls under analysis. Is it an analysis of form? Or is it a material analysis? Or is it an analysis that is also aware of the historical context, the media conditions, the history of performance? I would say that analysis is still a relatively open concept. That means that very different possibilities for interpretation seem to play a role. And we actually also got very different guiding ideas in your introductory statements, for example, with you, Anatol, more a material-relatedness; with Katharina Klement perhaps also a working off of the premiere situation; Thomas, with you, on the one hand, the premiere situation, but also – you mentioned several times – the performances canonised in the history of performance, so that we can observe very, very different moments there, which now, however, cannot all be grasped under a traditional concept of faithfulness to the work, but are oriented toward different ideas. That’s why, as an outside historian, I would be very interested to know how we should deal with these traditional descriptive categories.

TG: I think it’s important to see that there is not necessarily a school of interpretation here. I think that’s an essential difference compared to piano music that has been played a thousand times. The pieces that we played have not been played that often, especially not in this holistic framework. In this respect, one can almost always speak of a new first performance, depending on the situation of the room. So, the ‘instrumentation’, too, if you like, that of the loudspeakers, is always different and very strongly changes the feeling of how material is handled.

RF: To answer Nikolaus’s question: Analysis in a broad sense. This includes composition technique, as in the Backhaus example: There are certain musical structures, something comes back, there are symmetries within the composition, and so on. But also the historical context, Katharina Klement, for example, respected Xenakis’s sonification instructions and mapped the tracks to the speakers in the same way Xenakis did. But analysis also includes a philological approach for sure: What is the ‘text’, which versions exist, are they consistent, how do they relate to each other but also to different performance situations, etc.?

This is especially important for interpretation and pushes us back to the essential question: What shall I do with an analytical insight? Is it of any use to me and how can I musically implement it?

Perhaps in electroacoustic music one is even more forced to find new solutions because there is no broad historical performance practice. I think it is easier to perform a historically informed Scarlatti on the harpsichord than to realise a historically informed performance of Persepolis or Concret PH, where you would need 435 loudspeakers as in the Philips Pavilion in 1958. Today, moreover, we have completely different loudspeakers. I would say: We are constantly playing Scarlatti on a grand piano when we perform historical electroacoustic music nowadays.

TG: Maybe Jan can say something about that. The performance situation of Concret PH with 435 bad loudspeakers – from today’s perspective – is, of course, quite different than having 21 very good loudspeakers in the Klangtheater.

JB: I did not hear how it sounded at that time. There are only stories that often talk about the whole pavilion, where not only Concret PH was played, but also Edgard Varèse’s Poème électronique. I did not make a huge effort to read ten reviews about how exactly they perceived it. I rather asked myself: How do I hear the piece? How do I like it? And for me, Concret PH gives you the impression of sitting on glowing coal. That is why I used all available speakers. Unfortunately, I did not attend the premiere!

NU: May I perhaps ask again: What kind of research was done in preparation for the interpretations? For sure, we know about the performance situation in the Philips Pavilion, but you said you did not read through any other reviews. What was the research like with the others? What did you focus on in preparing for the performances? Katharina Klement, you read Reinhold’s dissertation and…

KK: Yes, thankfully. I did not know that Reinhold had done this detailed analysis of Bohor’s sound material. There is one track, which is always called “piano”. And Reinhold wrote that he always thought that this was not a piano. And I had thought the same thing, because as a pianist you can quickly hear whether there is a prepared piano somehow. His research revealed that it was produced on a Baschet instrument, which also had a keyboard. Xenakis’s idea was primarily to create metallic sounds in a wide variety. The title Bohor goes back to a knight from King Arthur’s round table in metal armor. To me, that is very poetic information that brings me much deeper into the piece. Or that the knight also had a scar, like Xenakis himself. So that there is probably an identification, which explains why the idea to use metal sounds came up in the first place. These connect you very much with a person. I probably got closer to Xenakis and the question why he made such a piece. So, thank you again for this extensive information! Reinhold also proved very clearly that much of what circulated as a supposed construction plan was just a later sketch to remix the piece. That confirmed my scepticism even more: What is the original? Or what is faithfulness to the original? Often what you find on the Internet or read in some text is not true.

RF: I think this is where the question of the existence of an ‘original’ is hidden: In musicology and philology, we have long since said goodbye to the idea that there must always be an ‘original’. But we musicians mostly still believe in this idea: We buy an ‘Urtext’ sheet music and think: “Ah, I got the original!” Of course, in most cases it is a lie, as already the long explanations in the introduction might show. Often it is even unclear which versions of a composition exist, or there are different versions to choose from. This is exactly the point that makes Xenakis’s electroacoustic œuvre interesting for this discussion: He left a respectable chaos of different versions, which is thus a treasure trove for music-philological questions. For example, at the premiere of Concret PH in 1958 at the Philips Pavilion in Brussels, there were 435 loudspeakers, but there was also a spatial movement realised with a special hardware that is lost today. Moreover, what we call a ‘composition’ today, started out as a sonic intermission filler, conceived as an interlude between the performances of Varèse’s Poème électronique. Xenakis himself called it “interlude sonore”. Later, Xenakis did what many musicians have done for centuries: He made secondary use of his own material. This is sufficiently proven and known, for example, with Bach or Beethoven. Xenakis has thus edited the Interlude Sonore somewhat and published it as the electroacoustic piece Concret PH in a new stereo version. And it has been published several times in different mixes. This led to a rich collection of source material, which is contradictory, and to which you have to relate as an interpreter. You are forced to choose what to refer to. In this respect, we get caught up in the ontological discussion: What actually is the work? What is the identity? Is it one version or many different ones? Or is “the work” what it tells me? Or is it something that I only help to become physical reality through my interpretation? In electroacoustic music one very quickly encounters these questions. That is why it lends itself to this discussion. At that point I would be interested in the musicological perspective.

Michelle Ziegler (MZ): I think many aspects have already been addressed in the discussion, and the performances in the Klangtheater have also impressively shown the variety of possible answers and approaches to interpretation. Basically, the new phonographic technologies in the 20th century have permanently changed the relationship between text, performance and work. There are definitely differences between writings on paper and recordings on tape due to their media, material and technological peculiarities: The different writing tools and recording devices, the different carriers, as well as the associated media practices affect the creation, edition, preservation and performance of musical works. However, the performances of Xenakis’s electroacoustic work at the Klangtheater have also confirmed that there are certain analogies in the interpretation or performance practice between electroacoustic works and instrumental music, since the sound projection in tape music is not merely a negligible side effect but constitutes an essential part of the performances. It shapes the sonic appearance and updates it in the best sense (i.e., leads to different results). Such a lively performance practice can unfortunately rarely be experienced in early electroacoustic music due to sparse concerts. The underlying questions have been increasingly addressed in research in recent years (cf. Toro-Pérez/ Bennett 2018 and Akkermann 2022) and are also relevant with regard to the use of analogue and digital media in today’s music creation.

In the discussion, various references have been made to the historical events of the first performances. As with most performances of early electroacoustic music, Xenakis as composer often carried out the sound projection himself. Based on sketches for different performance spaces, one can assume that he certainly adapted the interpretation to the individual spaces. Does one also know what he did in the dynamics? Whether he was also very active there, like Luigi Nono, for example, in a lively shaping at the moment and on the spot?

RF: Live performances by Xenakis are a complex issue. He heard virtually nothing in one ear and mixed accordingly. Daniel Teruggi (see Friedl 2009) recalled working with him in the studio: He had to keep pulling down the left channel because Xenakis involuntarily turned it up much too loud to compensate for his partial deafness. This means already physiologically: Composers are not always the best interpreters of their works. They are probably even rarely the best interpreters of their works. This is also true of composers who conduct their own works. In this respect, it is quite questionable to tacitly assume that the composer’s version is the best.

This must always be kept in mind when discussing the concept of the work, because one can certainly hold the opinion that if a work allows diverse – even seemingly wrong – interpretations, this is an indication of quality, and one might claim: The more meaningful interpretations a piece allows, the stronger it is. This would be roughly Eco’s concept of the open work: a potential that evokes different meaningful versions.

I think this resilience of Xenakis’s electroacoustic works is impressive – despite the most diverse interpretations, they retain their identity: We could really hear opposing versions or even interpretations of the same work in different directions, as Thomas Grill did, for example. And this does not even need to end up in a contradiction. Nevertheless, is Thomas even allowed to say, “For this room I do this, and for the other room I do something else”? At least it corresponds exactly to Xenakis’s own interpretive practice to adapt the work to the performance conditions.

TG: I would like to interject here that the piece only allows for different interpretations if the material lends itself to it (as in Concret PH, Gendy 3 or Persepolis, which Anatol, Jan and I played respectively). With such a gestural material as in Gendy 3, which is also dynamic, one can of course work differently on the mixing desk than in Persepolis with its blocks of textures. There is no point in modifying that all the time because it is obviously just meant to be blocky. You can do slow movements but certainly nothing dynamic. In that respect, it is very important to listen to everything very carefully. It is not enough to look only at the concepts, but you also have to listen to what the material actually suggests in terms of possibilities. In my case, it meant to work out something between the material and a conceptual approach that serves both: listening and understanding.

RF: That was also Anatol’s approach, if I understood it correctly? Finally, the ear decides.

AW: Exactly.

TG: Similar with Jan. He tried to redo or reconstruct the immersion that is already given by the Phillips Pavilion.

JB: Yes, exactly. Reinhold was just saying that it was actually an intermission piece in the pavilion. It is interesting that in this performance here everybody was sitting and silent and looking at the centre, while people in the pavilion were moving in and out during Xenakis’s piece.

NU: To conclude, I would like to emphasise one more aspect: We heard the complete electroacoustic work of Iannis Xenakis on three consecutive evenings at the Klangtheater. I would be interested to know to what extent it played a role for your sonic realisations that your interpretations took place in the context of a performance situation so focused on Xenakis. In the course of the conversation, we have already established that from time to time it may have played a role in the awareness of the dramaturgy of the respective concert evening when two other weighty pieces were performed on the same evening and one did not want to overtax the listeners – for example, with too high volume. But nevertheless, we had a very exciting path in electroacoustic composing directly in front of us within three evenings, including technical developments, musical developments, very different performance concepts. I would be very interested to know how this could have inspired your own realisations. Maybe we can do a final round and include everything that you would like to say. Jan, would you like to start?

JB: Yes, gladly. I played the first day and it was the second piece. I mentioned earlier that I was probably a little too careful with the volume. We had been listening to a lot of Xenakis the weeks before, and we had come to the conclusion that you should be a little careful with the treble because otherwise it can be quite aggressive. In retrospect, it probably could have been louder. But my ears were not tired yet because it was only the second piece, and besides, that was not the most relevant issue for my interpretation. Otherwise, I enjoyed the piece very much: I like it very much, and I like listening to it very much. But I also extremely enjoyed hearing the other pieces really loud. I also noticed what that does. So next time maybe I would do it differently.

NU: Reinhold, do you want to go next?

RF: As I already described, I had chosen a simple solution. As part of three evenings of other spatially complex electroacoustic music by Xenakis, I presented S.709, his last electronic work, a single-channel noise piece. The decision to simply have it rain down mono from the ceiling, from a single central speaker above the audience, not only supported the brittle sonority, but also opened up space for the other spatialised works played the same evening. The dramaturgy of a concert, the sequence of works, always plays a role in interpretation as well, and we often tend to forget that.

AW: Well, for my interpretation this context didn’t play such a big role, but during the concert I found it really exciting that Jonas Hammerer played Taurhiphanie (1987) in the same programme with very many sound movements. And after my version of Gendy 3 came Persepolis – this sequence of very different pieces was quite interesting.

TG: Persepolis is quite a piece. My problem was that I was also involved in the preparation of most of the other pieces, so I had rehearsed and listened a lot the days before. Due to that, my ears were already tired when I performed Persepolis at the Klangtheater, I noticed that strongly. Thus, the task of performing it with verve on the last evening was not the easiest. I would certainly have played it louder if I had not already been so exhausted. And with such a piece, which lasts an hour, and which has such massive blocks of sound, it is always a question of economy, how one approaches the matter…

NU: … Of the listening economy?

TG: … Yes, but also of the physical economy, how you let the thing come close to you. Of course, you can take it to the limit, but I couldn’t do that anymore at that moment, I have to admit. There would have been more in it. In this respect, my interpretation was not entirely satisfactory for me. I liked the concept, but there would have been room for improvement in the execution, especially in the choice of volume. Also, since it was the last piece in the programme, it probably could have been a bit sharper.

CT: I had the feeling of a quite controlled directing and I think I succeeded in the performance almost as much as in my rehearsals. Nevertheless, you are often surprised during the performance of a piece that you don’t know as well as your own music. This was also the case with Hibiki Hana Ma. But this is exactly the exciting thing and the reason why I prefer active sound direction to a completely automated playback. The most amazing thing, though, was how quickly the 18 minutes went by. Maybe it got me a little bit. Since Xenakis exposes quite archaic layers in this piece – and with his music in general – it was all the more exciting for me.

KK: I played the first night and had rehearsed quite a bit. I had first listened to Bohor in stereo at my home. I then took my first steps at Klangtheater together with Christian Tschinkel. Christian rehearsed Hibiki Hana Ma and that is a completely different, very gestural piece with sound figures. For me that was very enlightening, because Bohor is always about sound masses. I then rehearsed a lot in the Klangtheater on my own and really enjoyed how differentiated these sound masses can be portrayed. Suddenly, I thought: Now I actually understand Xenakis and his idea of a granular sound mass. I was also very enthusiastic about the Klangtheater as an instrument. I realised how things interlock, how a certain instrument is simply necessary, almost like an organ. I just can’t play an organ piece on the piano.

TG: A special thing is that the sounds in the Klangtheater can seem very close, even if the speakers are seven/eight metres away. The dry acoustics and the full audience make it feel incredibly intimate. One is really enveloped by the sounds. Only this room, or rather such a dry room, can do that; you couldn’t do that at all in an acoustic space like a concert hall – it would create a completely different feeling. And you can work in much more detail here, because the sounds are much purer.

RF: That reminds me: We originally had the idea of playing the late work that returns to mono on old loudspeakers as a kind of historical performance.

TG: We had three Electro Voice speakers hanging in the room, but they were not positioned well. They blasted to the back of the room over the audience and would not have had the desired effect compared to the modern speakers. The sound of the new system we have now is very neutral: In conjunction with the digital mixing console, it is like a dissecting instrument.

RF: This shows us once again that in electroacoustics you are doing almost the same thing as a musician on stage who has to make similar decisions: Do I play certain old music ‘ahistorically’ on a grand piano, or do I prefer a contemporary instrument?

TG: Yes, this question exists for us just as much. What makes loudspeakers very different, for example, are the directional characteristics. These types, which we have now, radiate rather broadly and equally in all frequencies. These are very comfortable speakers to work with. The Klipschs, for example, which we could have used, have horn drivers that are more narrowly directed and thus have a different emission behaviour. They sound much more present and penetrate more into the room. It’s a decision you have to make, and it also depends on where people are sitting. The all-around situation here didn’t lend itself to using such highly directional speaker types. Moreover, it would have taken much more effort to arrange that accordingly for each piece or each evening and to get the right spatial effect. That’s why we decided to use the canonical situation of 21 periphonic speakers in the hemisphere and an additional four on tripods around the mixing console. This is a situation that we already knew and with which it was easy to rehearse.

MZ: Theoretically, if you were to take it even further, you would also have to use historical playback devices in order to restore the situation with Bohor in which the tapes could not be played back synchronised.

TG: And for Persepolis, even the tape change, due to the length of the piece [laughs]. We’ve used tape machines in concerts before, for various reasons: aesthetic, staging-related, but also functional reasons of the medium. It is just not so easy to find tape machines to play 8-track tapes…

RF: … And then you would have to get the tapes from the archives and will be faced with the problem that the originals are usually not available for performances…

TG: … And recovering it from a digital copy would be absurd.

NU: I think we have reached a very good point, and I would like to thank you very much for the exciting discussion.

Bibliography

Akkermann, Miriam (2022) Archiving and Re-Performing Electroacoustic Music; https://arem2022.wordpress.com/ (accessed March 26, 2024).

Friedl, Reinhold (2009) “Polyphone Monophonie – Interpretation und Freiheit in Iannis Xenakis’ elektroakustischer Musik”, in MusikTexte 122, 12–17.

Friedl, Reinhold (2019), Towards a Philology of Electroacoustic Music – Xenakis’s Tape Music as Paradigm, PhD thesis, Goldsmith University of London; https://doi.org/10.25602/GOLD.00027680 (accessed August 7, 2023).

Toro-Pérez, Germán, and Bennett, Lucas, eds. (2018) The Performance Practice of Electroacoustic Music. The Studio Di Fonologia Years, Bern: Peter Lang.

List of Figures

Figure 12.1: Loudspeaker positions in the Klangtheater. General plan by Thomas Grill, 2024.

Figure 12.2: Blueprint with positions of the loudspeakers for Persepolis. Collection Famille Xenakis DR, OM 27-4, p. 4.