Systems Learning through Counter-Stories of Finnish Socially Engaged Musicians

Heidi Westerlund  and Sari Karttunen

and Sari Karttunen

How to cite

How to cite

Outline

Outline

Introduction

Research approach

Relationality Defining the Socially Engaged Music-Making System

Socially Engaged Practice as a Counterforce to Elitism and Hierarchies in Institutionalised Music-Making and Education

Socially Engaged Practice as Enhancing Systems Learning in Higher Music Education

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Introduction

Despite increasingly critical voices (e.g. Westerlund 2006; Hallam and Gaunt 2012; Holmgren 2020; Manternach 2024), the master-apprentice model continues to be the main pedagogical model in higher music education. While securing the sustainability of such tradition, it also provides a model par excellence of what organisational researchers Argylis and Schön (1978) called “single-loop learning”. The latter is learning through making adjustments to correct a mistake or a problem – doing things right by following the established principles. However, the master rarely, if ever, encourages the type of learning that digs into the morality of musical practices and calls for a change of values – “double loop learning” (Argylis and Schön 1978)1. Indeed, in his Teaching Smart People How to Learn, Argylis stated that “highly skilled professionals are frequently very good at single-loop learning”, but when their strategies do not seem to work, professionals “become defensive, screen out criticism, and put the ‘blame’ on anyone and everyone but themselves” (1991, 4).

The concept of triple-loop learning has been further developed to refer to organisation-level learning and systems-level transformation “concerned with the underlying purposes, principles or paradigms” (Tosey, Visser, and Saunders 2011, 294), and hence shifting attention from the knowing subject to the social conditions of knowledge construction. Such a situation may occur, for instance, at a time of great societal upheaval that threatens the authority of professional knowledge or pushes the experts out of their comfort zones to deal with uncertainty.

While triple-loop learning may be felt as risky because it might shake the status quo of the practice and the base of established expertise causing professional insecurity, systems-level learning may become necessary for contemporary organisations that are forced to adapt to complex, rapidly changing societies (Väkevä, Westerlund, and Ilmola-Sheppard 2017). For higher music education, this adaptation may be a matter of its very sustainability, even survival, since “in vulnerable systems even small disturbances may cause dramatic social consequences” (Folke 2006, 253). Sociologists widely claim that all institutions in late modernity can be expected to respond to societal challenges (Giddens 1990; Folke 2006) and in this way constantly reclaim their legitimacy. Sustainable transformation requires abandoning the assumption of “a stable and infinitely resilient environment where resource flows could be controlled” (Folke 2006, 253).

In this chapter we will explore reflections of socially engaged musicians in Finland, arguing that their practices hold the potential for triple-loop learning in the context of higher music education. The term “socially engaged music-making” refers to practices that carry a variety of names, ranging from participatory and community-based music, to socially responsible and impactful music-making, and to artistic citizenship. Such practices manifest a social turn (Charnley 2021) in the music industry, expand musicians’ professionalism (Westerlund and Gaunt 2021), and, as we suggest, provide the potential for wider critical systems reflexivity (Westerlund et al. 2021) and change in higher music education. Involvement in such practices has been encouraged as contributing to a musician’s employability (e.g. Bartleet et al. 2019). However, as our earlier research (Westerlund and Karttunen 2024) shows, socially engaged music making can be artistically rewarding and educative for the musicians themselves and can thus inform a higher music education that wishes to “co-evolve as a part of the society” (Väkevä, Westerlund, and Ilmola-Sheppard 2017, 135) while safe-guarding the meaningfulness of professional music-making.

Research approach

Our data consists of the survey responses and semi-structured interviews of ten musicians who are involved in socially engaged practices in Finland. This data was extracted from a larger data pool gathered through an open call addressed to musicians who were working to simultaneously achieve both musical and social goals. Out of the 63 survey respondents, 20 musicians were invited for an individual interview via Zoom, following the principle of maximum variation among the respondents who showed interest in developing their practice. In the purposeful “second stage sampling” (Barbour 2022, 3), the data was further narrowed down to ten interviews fulfilling the criterion of a completed higher music education degree either from any of the music degree lines of the music university, the Sibelius Academy, or the universities of applied sciences in Finland (Table 1). All of these degrees involved performance and music-making as a central element of the curriculum (performance, music education, church music, composition, etc.).

| Pseudonym2 | Duration of socially engaged practice (years) | Musical qualifications (highest level)3 | Qualifications in other disciplines (highest level) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aaro | 1–5 | BA* | MA |

| Anne | > 5 | MA | None |

| Iiris | > 5 | MA* | None |

| Katriina | 1–5 | BA | MA |

| Leo | 1–5 | MA* | None |

| Liisa | > 5 | MA | None |

| Maria | > 5 | MA | None |

| Markus | > 5 | BA | MA |

| Paula | > 5 | MA | None |

| Susanna | > 5 | MA | MA |

Table 1: Demographic and educational profiles of the interviewees. Source: Own illustration.

The sampling strategy reflects an iterative, abductive analysis process in which the first-round analysis on work values and career orientation (Westerlund and Karttunen 2024) indicated that this sample involves systems-level reflections. The interviews, conducted in Finnish in 2021 and each lasting approximately 90 minutes, covered themes such as training and career path, motivation for undertaking socially engaged practice, beliefs about achieving social impact, content and process of work, internal monitoring and evaluation, as well as context and constraints.The following research question was posed for the data set comprised of the ten musicians with higher music education background: How do musicians reflect upon their socially engaged work and how can their reflections inform professional education in music?

Since the data confirmed Thomas Turino’s argument that participatory practice should be conceptualised as a “different form of art and activity entirely” (2008, 25), we analyse socially engaged music-making as a distinct social system, a sense-making framework of principles and ideas that differs from the traditional concert hall practice. A social system can be identified when there is a boundary of some kind that is understood to mark where the system ends, or, as in this study, where the boundary is a point of recognised relationship (Capra 1997). The musicians’ reflections were organised as counter-stories that provide “a context to understand and transform established truths or legitimising narratives and associated frameworks for meaning-making” (Urmitapa, Azad, and Hussain 2022, 61). They allow us to see how the musicians positioned themselves and their practices in their sense-making processes. The analytical outcomes are meant to be “devices […] to organise a debate about ‘change to bring about improvement’” (Checkland and Poulter 2006, 18); they are thus heuristic aids and tools for learning about reality, rather than representations of reality.

We will first outline how the relationality in the practitioners’ reflections defines the purpose and quality of socially engaged music-making as a social system. We then illustrate how the musicians frame their practice as counter-stories, by organising the data in terms of what socially engaged practice does in society and education, and what the practice means for the musician’s status. Finally, we elaborate how socially engaged practice, as reflected by the Finnish musicians, could enhance systems learning – the double- and triple loop‑learning – in higher music education.

Relationality Defining the Socially Engaged Music-Making System

The interviewed musicians describe their socially engaged practice in terms of relationality, interactions, and complex interdependencies. They used terms such as “a human being for another human being”, “touching”, “encountering”, “listening to the people”, “coalescence with others”, “communication via music”, “encountering other people via creativity”, “mutual learning”, and “learning from participants and peers”. The practice was described as an active participatory approach in relation to people; not simply for people but rather with people. The bodily interaction was emphasised by many of the interviewees: “I can feel it in my body […] it’s really touching. […] it’s the moment of encountering […]. It’s a means of being able to be together and meet each other in it, and that’s the thing.” (Maria) The musicians explain how working outside of arts institutions had challenged them to develop a sensitivity and responsiveness towards the context:

I first thought that when you go and work in the neighbourhoods […] people will listen. It doesn’t work that way at all. […] You meet people who have no interest in attending a concert, so you must approach them in a completely different way. […] I noticed that my playing style changed a lot depending on where I was and who was listening, because it became kind of automatic that I reacted to the situation. (Paula)

This social improvisation in varying situations further teaches the musicians how to learn together with the participants. They explain how relationality has changed their approach to music-making, how they have learned to give up their instrument-specific expertise, as well as to reveal their own ignorance and lack of skill, and have built up the courage to experiment with new instruments, approaches and environments. They describe how they had left behind their learned musical genre and expanded their occupational tasks, or had taken a step toward collective authorship for compositions. They describe how decision-making in collaborative processes is shared with non-professionals; how they refrain from having a ready-made concept to be applied, and instead may take a step back and listen; and how they consciously reduce their expert agency to give room for other participants and situations “where you cannot control the end result” (Liisa).

These non-hierarchical participatory music-making processes have not, however, led the musicians to give up artistic criteria. Rather, they use musical criteria as being integrated with the values that the practice provides for its participants, and have personal ways to deal with the potential conflict between their own artistic ambitions and the participants’ interests. Some of them separate their other artistic work and the socially engaged practice, while others had adjusted their entire view on their professional goals, conceptions of quality, and ways to evaluate success. While the communal working processes were found equally crucial to, or even more important than, the final outcome, the musicians describe how they enjoyed being released from the pressure to subordinate all music making to the ideal of a perfect public performance and how participatory music-making with non-professionals was a pleasurable, alternative way to make use of their musical skills. Such a practice requires an attitude shift for a musician with a traditional education, as one of them explained:

You need humbleness, since […] these things rarely go as you plan. […] It demands a thinking process [to conceive] that this is valuable in itself […] so every now and then there has been cross wrestling between one’s own goal-directedness and the conditions of the community. (Susanna)

Socially Engaged Practice as a Counterforce to Elitism and Hierarchies in Institutionalised Music-Making and Education

Whilst the musicians describe the purpose of the socially engaged practice for themselves, they also mentioned what it did differently compared to the established concert institutions or state-funded music education system. Their sense-making of the principles and ideas of the two systems occur not just in relation to the people, participants and the various non-conventional contexts (e.g. sheltered homes, schools, hospitals, prisons, neighbourhoods, parishes), but as “a boundary critique” (Ulrich and Reynolds 2020) in relation to the dominant institutional music industry and music education.

Correcting Exclusionary and Distancing Hierarchies

In the interviewees’ descriptions, socially engaged music making differs from the traditional concert hall practice in “blurring the boundary between the artist and the audience” (Westerlund and Karttunen 2024, 503). The musicians reflect on how they became aware of the limitations of the socio-spatial arrangements of concert hall practices:

I’ve been thinking a lot about why the Western way, where all the halls are built so that there is a clear boundary between the performers who are on stage and the listeners who are in the audience in their assigned places, is so strong in everything we do [laughs] […] we [socially engaged musicians] […] dismantle it or lower it or change it in some way. That it’s not so much either/or, either the performer or the listener, but that you can be both. (Iiris)

The musicians criticise how the focus on achieving the highest level of musical quality as the sole criterion of value in concert hall practice steers music teachers’ awareness and actions independent of the context (schools, music schools and higher music education) and how the socially engaged practice has developed tolerance for incompleteness and awareness of multiple context-specific values: “In these productions I’ve started to think about the question of value, what we really value and why. […] When in a way something different can also sound pretty good.” (Liisa) Perfectionism was seen as a particular feature of the classical music performance tradition, in which socially engaged music making was correcting the hierarchical and one-directional communication tradition and formed “a radical alternative” (Westerlund and Karttunen 2024, 508):

There is no second prize in [classical orchestra] music, there is only a first prize. […] Sometimes it makes me laugh, […] that you really do go to that university and they tell you about musical creativity and stuff. Then in reality your discipline is tougher in the orchestra than in the army. Even in the army you can get away with more than you can in the orchestra. (Leo)

Socially engaged practice shifts the focus towards interaction that allows for the musician’s own improvisation.

The world of classical music pursues excellence and a certain level of technically honed performance […]. Here [in socially engaged practice] you can at least gain access to a “world of rest” in which true communication and the meaning of what it is that we are actually doing becomes better defined. (Maria)

This deliberate distancing from the known tradition was typical of all of the interviewees. They had also become aware of how music is still used as a tool for creating divisions in society and wanted to resist exclusive categorisations, such as the talented vs. the untalented, the creator vs. the audience, or the musical vs. the non- or extra-musical, and instead, to promote the understanding that anyone can participate in music making, anytime, in a fulfilling way.

Correcting the Harm Caused by Past Music Education

The musicians’ reflections manifest systems awareness in which they criticised the past music education system for having reduced rather than increased people’s possibilities in engaging with music:

[…] the Western academic idea [is] that you have to be able to do it in a certain way, according to certain rules, for it to be acceptable. So if you haven’t had the right education, you’re given the impression that you have no business doing it. […] Our concept of music education is actually rather narrow, if you think in global terms. (Aaro)

The musicians’ cultural contribution to society is taken to another level when the musicians describe their work as an opportunity to ‘correct the harm’ that the past model of overly talent-seeking music education had caused for some parts of the population that they were currently working with in their socially engaged practice:

[P]eople whose mouths had been shut in primary school now come to me and say that 50-60 years ago they told me not to sing and I haven’t sung since then. It is such a huge injustice. […] I think it’s terribly elitist. (Katriina)

People have terrible traumatic experiences with these things, for instance the school singing tests are a good example, being forced to sing in front of a class of other kids. […] It’s just horrible, it’s just shocking. (Markus)

Whilst public singing exams have not necessarily been widely practised for decades in Finnish general education, the older generations can carry with them memories of these humiliating situations all their life and can seek possibilities of radically alternative practices to overcome the distress and shame. Socially engaged music-making can thus function as a curing mechanism for those who have previously been traumatised by music lessons and who wish to reclaim their cultural rights for active music-making.

Correcting the Hierarchical Mental Models within Music Professionalism

Since socially engaged practice concretely dismantles the detachment between professional musicians and the audience, involvement in such practice requires the unpacking of hierarchies with regard to who is entitled to be a performer and who is allowed to listen only. This unpacking of dichotomies may require a conscious change of once-learned mental models:

[…] It’s a kind of resetting my head […] that there are no already-musicians and not-yet-musicians. There are musicians […]; we should look for the lowest common denominator in what we do, so that we can do it together, rather than the things that you don’t know how to do yet. (Iiris)

Some of the interviewed musicians had redefined their role in relation to the specific marginalised groups with whom they interacted (e.g. residents in old people’s homes, patients in hospitals, prisoners, intoxicant abusers in urban neighbourhoods or children with disabilities). They tolerated the blurring of boundaries that are meant to sustain the highest level of professional quality and excellence in music making, and instead described also other important experiential qualities and social values that can be brought about in socially engaged music making (Westerlund and Karttunen 2024).

Working across sectors and outside the arts contexts, such as in hospitals, did not however mean giving up their identity as musicians. Rather, an artistic identity was described as an asset, for instance, in creating trust when working and reconstructing in an overly medicalised context:

When working with specific groups, especially older people with learning difficulties, but also mental health service users and young unemployed people, […] it is important for me to keep a pretty strong identity as an artist. Because then I come from outside the system, and it’s much easier for me to create the kind of relationship I want with those people. I’m not a social worker, and I’m not a nurse […]; I want to be there as someone who is easy to approach. (Aaro)

The shift of professional interests when working with various groups of people was, however, met with scorn and astonishment by many of their musician colleagues, illustrating how systems’ boundaries operate. Since the work of socially engaged musicians does not align with the dominant sense-making frame, the involved musicians can face blame for violating professional standards. As Paula says: “Other artists wonder what the point is of wasting work time playing to some alcoholics.” For some, this questioning of the value of their work had created an occasional sense of shame, yet also an urge to fight against the demeaning status and service aspect of socially engaged practice. For them, the ossified way of judging revealed the one-dimensional system of professional music making. For instance, Anne wonders “how has it been thought in our structures in the first place, like what is the interface between making art and that of […] ‘being a servant’, like when does valuation begin?”

Importantly, the distancing of oneself from the status quo of the dominant system and its ‘star culture’ was related not simply to the participants, but also to the musicians’ own needs and values as artists and human beings: “I feel that […] I have not only been giving there but also receiving, and this has been really valuable for me.” (Iiris)

Socially Engaged Practice as Enhancing Systems Learning in Higher Music Education

How then can the musicians’ reflections on their socially engaged practice inform today’s professional education in music? The data clearly indicates that the ten socially engaged musicians with traditional higher music education background had developed systems reflexivity (Westerlund et al. 2021) – the capacity to identify, critically challenge and reimagine the structures of current systems. Their reflections can be seen as counter-stories that aim to rethink, revitalise and establish “anew the aesthetic distance from life and people” (Peters and Lankshear 1996, 16) that in the modernist era alienated people from art and artists; in other words, the counter-stories point out that the co-presence of the community in ‘an artwork’ can in itself illustrate (and perform) how the dichotomous aesthetic notion – with its inherent division between artistic production and consumption – is not a necessity but a product of historical development.

Becoming Aware of Path-Dependency

While being educated within the established professional system and still working as insiders in it, the musicians had reconceptualised their expert work and describe it as a process where they constantly learn and feel comfortable with, or even cherish, the feeling of never being completely prepared for the practice. Taken together, the musicians’ counter-stories reveal what systems thinkers have called “systems archetypes” (Kim 1992), which create stagnant path-dependencies that resist change. In depicting colleagues’ attitudes, in particular, the musicians’ reflections focus on the broader systemic and structural issues of professional music-making, such as normalised and accepted elitism and fixed mental models of what success and quality mean in music performance and education.

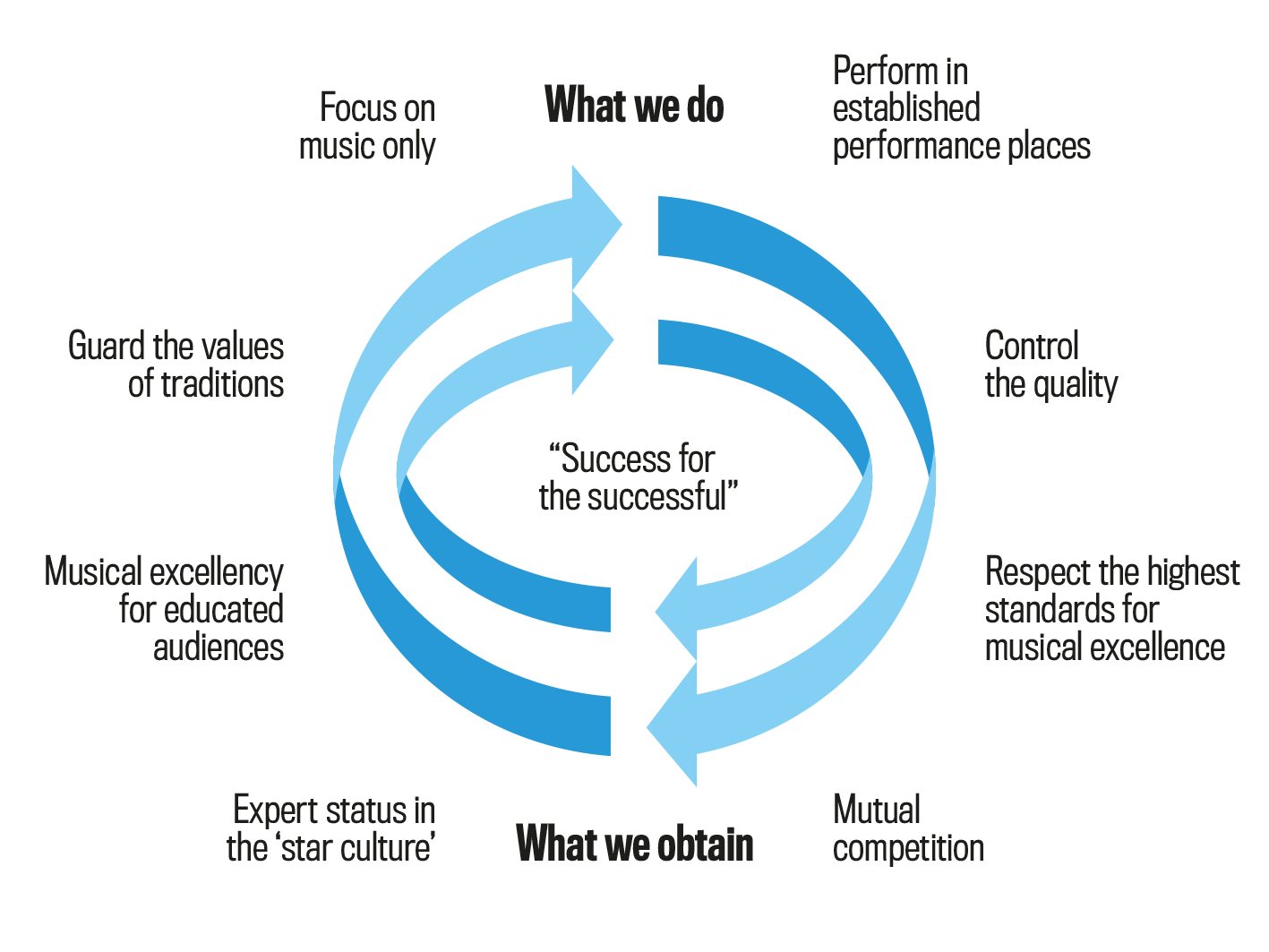

Väkevä, Westerlund, and Ilmola-Sheppard have described this path-dependency with “a linear model” (2017, 137), in which the music teacher’s role is to sustain the system and its once-established purpose, and in this way to create stability instead of becoming a transformative agent who can enhance cultural and institutional systems change. Moreover, according to the linear model, the music education systems are silos with “no other connections with society other than being resourced on the basis of selecting the musically talented in the population, providing the optimal conditions for training professionals” (ibid., 138). The linear model can thus create a self-fulfilling prophecy that in systems literature is called the “Success to the Successful archetype” (Kim 1992), which highlights the centrality of path-dependency in stagnant systems. According to Kim, the Success to the Successful archetype “continually pushes us to do whatever has been successful in the past” and sustains a structure that systematically eliminates “the other possibilities that may have been equally viable” (ibid., 25; see Figure 1 systems model illustrating how the archetype is produced).

Figure 1: Success to the Successful archetype (Kim 1992) in the music industry and higher music education (based on the identified discourse in the interview data). Source: Own illustration.

Kim has suggested that managing the problem of the Success to the Successful archetype requires looking at the situation from a more macro-level perspective and asking ourselves the question “What is the larger goal within which the situation is embedded?” (Kim 1992, 25). As the Success to the Successful archetype results from and is strengthened by single-loop learning, which does not involve critical reflexivity on the purposes and values of activities, the transformative solutions for the archetype problem require the type of double-loop learning that digs into the wider consequences of practice. The musicians of this study recognised how the elitist hierarchies as a normalised part of professional practice effectively continue sustaining unsustainability. Hence, their reflections challenged the morality of the professional system’s social distancing.

Some of the musicians could identify the moments and specific events when they started understanding how the established system operates and when their social consciousness was awakened. One of the musicians describes such a moment during her year in higher music education:

I saw a documentary from a hospital on long-term patients’ departments and I cried all the time when watching it. I thought, Oh my god, how can it be. And then I saw in the [local parish] journal that they were searching for volunteers to make music in these departments. And I signed on. […] It was during my second or third year of studies and it was somehow so wonderful, because in my studies it was all circulating around my own ego, about developing my own musicianship. (Iiris)

Unlearning and Developing a Learner Identity

The multiple learnings that the musicians described can also be defined as paradigmatic unlearning both at the individual and institutional action levels as both are permeated by the long-established mental models. The interviewees described how they had distanced themselves from the established notions of what music is, what professional musicians’ principles and aspirations ought to be, and how and where musicians should behave. Some of them expressed being tired of the very institutional ‘machinery’ in which they had been educated, explaining how they fought against the establishment:

I’m really tired of the institutions. […] You always have to draw a deep breath before you have the strength to defy it. That’s why, in a way, I’ve now somehow ended up doing research, so that there would be some base from which to […] build up some kind of fight against the machinery [laughs]. (Liisa)

The musicians had developed what has been called a “learner identity” (López-Íñiguez and Bennett 2021) with an experimental attitude beyond any previously learned set of professional competences. As they explain, a socially engaged practice “educates the musician to understand […] what this is all about in the deepest sense”, which also translates to the traditional concert stage: it “starts making it better there as well” (Maria). Some of them had developed new conceptual understandings of professional practice in order to market their practices, whilst some experimented with shared decision-making and distributed leadership that are less typical in the music field, or co-created communities with a realisation of temporary safe spaces in order to consider a variety of participant expectations and experiences. They describe how every situation can be taken as a moment of curiosity, and how one can continuously learn from all participants: “I have taken this attitude that I always learn from every situation […], including this situation now; I don’t limit learning to some specific ones”. (Aaro)

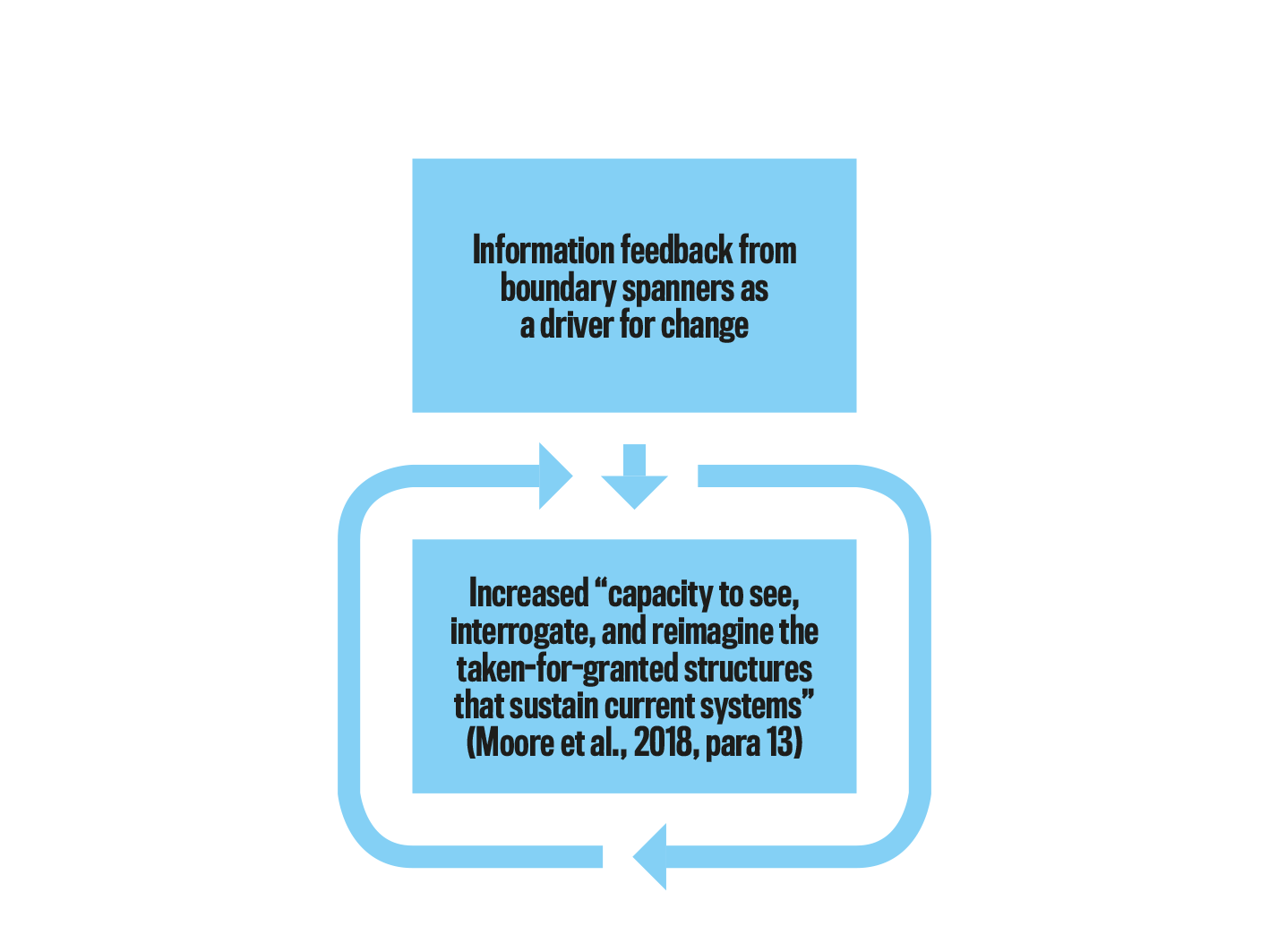

Figure 2: Double-loop learning leading to continuous systems learning in the music industry and higher music education (based on the identified discourse in the interview data). Source: Own illustration.

The musicians’ reflections thus reached well beyond a reflection on patterns of success and failure within the single-loop learning in master-apprentice practice, which leaves the values of action unchallenged and unchanged. Instead, they described the ethico-political and moral questions they had engaged with, and how they had questioned at a fundamental level the monolithic ends of instituted practices and the deliberate ignorance of their consequential societal exclusions and vulnerabilities. They identified the value of socially engaged practices from multiple perspectives beyond tradition, any specific musical genre and any learned mental models towards transforming not just the professional field and education but also society at large. Their positioning “provides a powerful moral orientation towards alternative models of society” and resists the way “intrinsic musical values are traditionally distinguished from social values that are categorised as non-musical and extrinsic to musical values” (Westerlund and Karttunen 2024, 514).

Musicians as Boundary Spanners

Through their systems reflexivity, the musicians positioned themselves as boundary spanners (Barrett and Westerlund 2024) between different sense-making frameworks of principles and ideas. The boundary spanning nature of the musicians’ work had taught them to navigate between systems and move from one value-system to another without experiencing a conflict. They knew as insiders how the hegemonic system operates but they were also able to break the boundaries of established mental models, taken-for-granted social designs and institutional settings. Indeed, the systems researcher David Stroh writes that “if you are not aware of how you are part of the problem, you can’t be part of the solution” (2015, 4). Boundary-spanning change agents must encompass “deep insights into root causes that incorporate their own thinking and behavior” (ibid., 18) in order for them “to develop a new way of being, not just doing” (ibid., 20).

The kind of learning that the musicians described provides information feedback that can function as a driver for change within higher music education systems that want to be open systems and at the forefront of change (Figure 3). An example of the performative power of experiencing the difference of such practices is described by one of the musicians who had been invited to the closing event of a course in participatory music making organised at the Sibelius Academy: “[…] I remember how I woke up there to realise how their starting point was that […] we are here for you or together with you, not simply performing to you […] there was this element that came somehow closer.” (Iiris) Socially engaged music-making in itself may therefore provide a concrete experiential way of illustrating the power of alternative practices and changing mental models. The performed information feedback – performing the difference (Laes and Westerlund 2017) – can function as a strategic driver for change.

Rather than calling for a revolution, this study’s musicians embraced smaller-scale incremental change: “Personally, I’m satisfied that I can keep doing this and I can see the effects. And they are always local and small, but yes: by doing, that’s my way.” (Anne)

In higher music education contexts, boundary spanning may require the leaders to engage with the strategic complexity of practices and “to establish direction, alignment and commitment across boundaries in service of a higher vision or goal” (Yip, Ernst, and Campbell 2016, 3). Instead of seeing boundary spanning as a risk in a tradition-guarding context, it can be seen “in a positive light as the beginnings of exercising our moral imagination, of envisioning the possibilities and opportunities of systems transformation, and having the courage to […] enter the unknown” (Barrett and Westerlund 2024, 84). In other words, higher music education could more actively provide spaces for the students to engage with double-loop learning and reflexivity concerning the social conditions of knowledge construction in the competitive expert culture.

Figure 3: The transformative potential of boundary spanners’ insider-feedback in higher music education (based on the identified discourse in the interview data). Source: Own illustration.

Conclusion

The counter-stories of the ten socially engaged musicians in the Finnish context manifest the type of systems reflexivity that enabled them to identify the root causes of what they considered to be non-acceptable hierarchies and elitism in the music field in contemporary society. In the musicians’ descriptions, their practices appear as a necessary, transformative cultural force, which can open the gaze of higher music education beyond instrument-specific traditions, musical genres and the master-apprentice model for teaching and learning. The reflections reach beyond previously suggested cures for the path-dependencies of higher music education, such as including more musical genres and improvisation in performance programmes (Sarath, Myers, and Campbell 2017). The musicians lead us to ask: Can higher music education afford to ignore the social turn that is claimed to have become increasingly evident also in the arts (Bishop 2006; Charnley 2021)? The fundamental unlearning and purposeful lowering of the exclusionary expert status quo exemplifies deep double-loop learning, hence providing the potential for higher music education to consider including the experience of socially engaged musicians’ boundary-spanning knowledge in professional education and in this way enhancing triple-loop learning in higher music education institutions.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as part of the project, Music for social impact: practitioners’ contexts, work, and beliefs (2020-2023), funded by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council (grant number AH/S005285/1) and co-funded by Social Impact of Making Music (SIMM)4. The larger project was conducted in four countries: the UK, Belgium, Colombia and Finland. Ethical approval was sought and obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Guildhall School of Music & Drama that co-ordinated the project. The study has also been funded by the Center for Educational Research and Academic Development of the Uniarts Helsinki.

Endnotes

-

We use the term “morality” of professional work (Tsoukas 2018) and of musical practices in order to refer to the musicians’ “values-in-use, beliefs-in-context, judgments-in-practical-settings” in their work (Cromdal and Tholander 2014, 161; see also Minnameier 2014), however acknowledging that ethics and morality are commonly used interchangeably.↩︎

-

The participants were not asked to identify their gender in either the survey or the interviews. The pseudonyms follow the assumed gender within a binary framework of first names.↩︎

-

Asterisks indicate the additional in-service training in community musicianship offered at several Finnish universities ofapplied sciences since 2017.↩︎

-

https://www.simm-platform.eu/(accessed April 22, 2025).↩︎

Bibliography

Argylis, Chris. 1991. “Teaching Smart People to Learn.” Harvard Business Review 69, no. 3: 99-109.

Argyris Chris, and Donald Schön. 1978. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Barbour, Rosaline. 2022. “Theoretical Sampling.” In Sage Research Methods Foundations, edited by Paul Atkinson, Sara Delamont, Alexandru Cernat, Joseph W. Sakshaug, and Richard A. Williams. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Barrett, Margaret, and Heidi Westerlund. 2024. Music education, ecopolitical professionalism and public pedagogy: Towards systems transformation. Cham, Switzerland: SpringerBriefs in Education.

Bartleet, Brydie-Leigh, Christina Ballico, Dawn Bennett, Ruth Bridgstock, Paul Draper, Vanessa Tomlinson, and Scott Harrison. 2019. “Building sustainable portfolio careers in music: insights and implications for higher education.” Music Education Research 21, no. 3: 282-294. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2019.1598348.

Bishop, Claire. 2006. “The Social Turn: Collaboration and its discontents.” Artforum International 44, no. 6: 178-183.

Capra, Fritjof. 1997. The Web of Life. London: Flamingo.

Charnley, Kim. 2021. Sociopolitical Aesthetics. Art, Crisis and Neoliberalism. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Checkland, Peter, and John Poulter. 2006. Learning for Action. A Short Definitive Account of Soft Systems Methodology and its use for Practitioners, Teachers and Students. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Cromdal, Jakob, and Michael Tholander. 2014. “Morality in Professional Practice.” Journal of Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice 9, no. 2, 155-164. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1558/japl.v9i2.25734.

Folke, Carl. 2006. “Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social-ecological systems analysis.” Global Environmental Change 16, no. 3: 253-267.

Giddens, Anthony. 1990. The Consequences of Modernity. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Hallam, Susan, and Helena Gaunt. 2012. Preparing for Success. A Practical Guide for Young Musicians. Institute of Education. University of London.

Holmgren, Carl. 2020. “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice’s apprentices: A critical analysis of teaching and learning of musical interpretation in a piano master class.” Svensk tidskrift för musikforskning 102: 37-65.

Kim, Daniel. 1992. Systems Archetypes 1. Diagnosing Systemic Issues and Designing High-Leverage Interventions. Waltham, MA: Pegasus Communications.

Laes, Tuulikki, and Heidi Westerlund. 2017. “Performing disability in music teacher education: Moving beyond inclusion through expanded

professionalism.” International Journal of Music Education 36, no. 1: 34-46. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761417703782.

López-Íñiguez, Guadalupe, and Dawn Bennett. 2021. “Broadening student musicians’ career horizons: The importance of being and becoming a learner in higher education.” International Journal of Music Education 39, no. 2: 134-150. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761421989111.

Manternach, Brian. 2024. “Master of None: Challenging the Master-Apprentice Model.” Journal of Singing 80, no. 4: 447-454. DOI: https://doi.org/10.53830/sing.00028.

Minnameier, Gerhard. 2014. “Moral Aspects of Professions and Professional Practice.” In International Handbook of Research in Professional and Practice-based Learning, edited by Stephen Billett, Christian Harteis, and Hans Gruber, 57-77. Dordrecht: Springer. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8902-8_3.

Peters, Michael, and Colin Lankshear. 1996. “Postmodern counternarratives.” In Counternarratives. Cultural studies and critical pedagogies in postmodern spaces, edited by Henry Giroux, Colin Lankshear, Peter McLaren, and Michael Peters, 1-39. New York and London: Routledge.

Sarath, Edward, David Myers, and Patricia Campbell. 2017.

Redefining Music Studies in an Age of Change: Creativity, Diversity, and Integration. New York and London: Routledge.

Stroh, David. 2015. Systems Thinking for Social Change. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green.

Tosey, Paul, Max Visser, and Mark Saunders. 2011. “The origins and conceptualizations of ‘triple-loop’ learning: A critical review.”

Management Learning 43, no. 3: 291-307. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507611426239.

Tsoukas, Haridimos. 2018. “Strategy and virtue: Developing strategy-as-practice through virtue ethics.” Strategic Organization 16, no. 3: 323-351.

Turino, Thomas. 2008. Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago

Press.

Ulrich, Werner, and Martin Reynolds. 2020. “Critical Systems Heuristics: The

Idea and Practice of Boundary Critique.” In Systems Approaches to Making Change: A Practical Guide, edited by Martin Reynolds and Sue Holwell, 255-305. 2nd edition. London: Open University and Springer.

Urmitapa, Dutta, Abdul Kalam Azad, and Shalim M. Hussain. 2022. “Counterstorytelling as Epistemic Justice: Decolonial Community-based Praxis from the Global South.” American Journal of Community Psychology 69, no. 1-2: 59-70. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12545.

Väkevä, Lauri, Heidi Westerlund, and Leena Ilmola-Sheppard. 2017. “Social Innovations in Music Education: Creating Institutional Resilience for Increasing Social Justice.” Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 16, no. 3: 129-147. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22176/act16.3.129.

Westerlund, Heidi. 2006. “Garage Rock Band – A Future Model for Developing Musical Expertise?” International Journal of Music Education 24, no. 2: 119-125. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761406065472.

Westerlund, Heidi, and Helena Gaunt, eds. 2021. Expanding Professionalism in Music and Higher Music Education. A Changing Game. Abingdon: Routledge.

Westerlund, Heidi, and Sari Karttunen. 2024. “The protean music career as a sociopolitical orientation: The mutually integrated, non-hierarchical work values of socially engaged musicians.” Musicae Scientiae 28, no. 3: 502-519. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/10298649231222548.

Westerlund, Heidi, Sari Karttunen, Kai Lehikoinen, Tuulikki Laes, Lauri Väkevä, and Eeva Anttila. 2021. “Expanding professional responsibility in arts education: Social innovations paving the way for systems reflexivity.” International Journal of Education & the Arts 22, no. 8.

Yip, Jeffrey, Chris Ernst, and Michael Campbell. 2016. Boundary Spanning Leadership: Mission Critical Perspectives From the Executive Suite. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.